In the Closet of the Vatican

By

5.28.19 |

Symposium Introduction

What kind of book is Frédéric Martel’s, In the Closet of the Vatican? Is it a work of serious investigative journalism, or is it dishy gossip meant to distract from serious discussions about clergy abuse? Maybe it’s French social theory using the homosexuality of the Catholic hierarchy as a case study. Some have described it as a complex, multifacted work, destined to be widely misunderstood, partly because of its campy humor, and mostly because of the filters through which it must pass: the sensationalism of the media, the casual homophobia of the public, and the malice of the network of right-wing Catholic blogs, Breitbart-style “news” sites, and supportive prelates intent on equating homosexuality and pedophilia. From another angle, it can be read as a work of queer studies, which provides a detailed account of a particular gay subculture. Perhaps it is some combination of the above.

The ambiguity of genre befits the ambiguities inherent in the topic of homosexuality in the Vatican. It is like a Rorschach test. I believe we can learn a lot from the responses. The most obviously revealing response comes from those who reflexively relate homosexuality to some form of corruption. This response reifies homosexuality and assigns it agency or causal power. That is how a priest’s homosexuality not only describes his sexual attraction to other men; it also causes, as if by magic, pedophilia, sexual abuse, moral decline, social degradation, and intellectual and spiritual darkness. The suggestion that gay priests are more likely to rape children, however, only works if homosexuality inclines anyone to do so. The response evident of mainstream journalists, no doubt playing into the publisher’s marketing strategy, have presented Martel’s work as salacious exposé. They focus on the suggestion that a great majority of Vatican officials are either gay men who have active sex lives or “homophiles” who replicate older forms of closeted gay culture. The implicit assumption is that homosexuality itself is somehow scandalous. Otherwise, such headlines wouldn’t be attention-grabbing. Another response, characteristic of liberal Catholics, concerns the timing of the book, which will be released on the day a major Vatican meeting about the abuse crisis is scheduled to begin. Will Martel’s book draw attention away from the response to that crisis? Worse: will it give fodder to the Catholic right, who are already weaponizing the clergy abuse crisis as they try to purge the priesthood of gay men? This defensive crouch, I think, concedes the framing of the narrative to the right.

Martel is not coy about what he thinks he’s doing and what it means. Using the methods of investigative journalism and relying on his advanced training in French social theory, he aims to uncover and detail “the homosexual sociology of Catholicism.” Martel clarifies the object of his study by contrasting it with the Vaticanologists who denounce “individual excesses.” “I am less concerned with exposing these affairs than with revealing the very banal double life of most of the dignitaries of the Church. Not the exceptions but the system and the model, what American sociologists call ‘the pattern’” (xiii). The system, constructed “on the homosexual double life and on the most dizzying homophobia” (xii), is expressed by 14 “great laws” or “Rules of the Closet” (xii). These rules, scattered throughout the sprawling and detailed text, return the reader continually to the systemic nature of his undertaking. I present them, decontextualized and in Martel’s words:

Rules of the Closet

- For a long time the priesthood was the ideal escape-route for young homosexuals. Homosexuality is one of the keys to their vocation. (8)

- Homosexuality spreads the closer one gets to the holy of holies; there are more and more homosexuals as one rises through the Catholic hierarchy. In the College of Cardinals and at the Vatican, the preferential selection process is said to be perfected; homosexuality becomes the rule, heterosexuality the exception. (10)

- The more vehemently opposed a cleric is to gays, the stronger his homophobic obsession, the more likely it is that he is insincere, and that his vehemence conceals something. (34)

- The more pro-gay a cleric is, the less likely he is to be gay; the more homophobic a cleric is, the more likely he is to be homosexual. (41)

- Rumours, gossip, settling of scores, revenge and sexual harassment are rife in the holy see. The gay question is one of the mainsprings of these plots. (60)

- Behind the majority of cases of sexual abuse there are priests and bishops who have protected the aggressors because of their own homosexuality and out of fear that it might be revealed in the event of a scandal. The culture of secrecy that was needed to maintain silence about the high prevalence of homosexuality in the Church has allowed sexual abuse to be hidden and predators to act. (92)

- The most gay-friendly cardinals, bishops and priests, the ones who talk little about the homosexual question, are generally heterosexual. (123)

- In prostitution in Rome between priests and Arab escorts, two sexual poverties come together: the profound sexual frustration of Catholic priests is echoed in the constraints of Islam, which make heterosexual acts outside of marriage difficult for a young Muslim. (129)

- The homophiles of the Vatican generally move from chastity towards homosexuality; homosexuals never go into reverse gear and become homophilic. (169)

- Homosexual priests and theologians are much more inclined to impose priestly celibacy than their heterosexual co-religionists. They are very concerned to have this vow of chastity respected, even though it is intrinsically against nature. (176-177)

- Most nuncios are homosexual, but their diplomacy is essentially homophobic. They are denouncing what they are themselves. As for cardinals, bishops and priests, the more they travel, the more suspect they are! (311)

- Rumours peddled about the homosexuality of a cardinal or a prelate are often leaked by homosexuals, themselves closeted, attacking their liberal opponents. They are essential weapons used in the Vatican against gays by gays. (388)

- Do not ask who the companions of cardinals and bishops are; ask their secretaries, their assistants or their protégés, and you will be able to tell the truth by their reaction. (537)

- We are often mistaken about the loves of priests, and about the number of people with whom they have liaisons: when we wrongly interpret friendships as liaisons, which is an error by addition; but also when we fail to imagine friendships as liaisons, which is another kind of error, this time by subtraction. (538) 1

Martel believes these rules have vast explanatory power. They constitute a “key for understanding”: the nature of some magisterial teachings, the direction and emphases of doctrinal enforcement, along with a host of recent scandals, political and diplomatic intrigues, the shape of the misogyny of priests and prelates, Pope Benedict XVI’s abdication, the current curial and right-wing opposition to Francis, the pervasive cover-up of sexual abuse, and the decline of vocations in Europe (xii-xiv).

These rules elucidate the book’s central theme: the duplicity or double lives of many Church dignitaries. What is the system that empowers so many to lead double lives? Mainly, this involves describing the central characteristics of the system, discerning its effects, and relating them to one another. Martel collects fragments he finds in archives, hears in personal testimonies, and discerns through interviews, including in interview subjects’ unintentional but revealing slips. His book connects these fragments to only to the Church’s public teaching, but to the personal intellectual influences of senior Church leaders, to character profiles he develops, and to the broader culture of Vatican priests, bishops, and nuncios.

The organization reflects Martel’s systemic aims. Between the introduction and the epilogue are four main headings: Pope Francis, Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI. Each major section is further subdivided into chapters, which address various topics, influences, events, characters, or intrigues. Together, they frame how Martel has come to understand the power-structure, culture, and ideological underpinnings of each papacy. At the start of each chapter, Martel provides a chart that lays out the main characters in each pope’s inner circle: the pope’s personal secretary, the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, the Secretary of State, and those who work under him. Of the four popes, Francis is by far the most sympathetic. Martel presents his analysis as a complement to what Francis has suggested at various points about the rigidity of those who lead double lives.

Besides the theme of duplicity, there are other, less obvious threads that weave throughout the sprawling text. Martel often notes when he finds a living interview subject effeminate. I take this to mean that the man has activated Martel’s gaydar. I suspect that this book, released internationally, is subject to more than one set of libel laws. Martel also compares what he calls “the parish” of gays in the Vatican to different gay communities. This includes mainly the “practicing” or “very practicing” homosexuals and the non-practicing “homophiles” who maintain an older form of closeted gay life. This, I think, makes some sense of the book’s campy jokes and sometimes its severity. Martel also consistently notes when he is impressed by someone’s French. He also tends to highlight the influence of French literature, philosophy, and theology. It turns out a substantial number of Church dignitaries have been influenced by Martel’s canon of gay French authors. Martel is clearly, unapologetically French. He finds the French church/state arrangement optimal. His own “Catholic atheism” has been influenced by French philosophy. It corresponds to the progress narrative regarding matters of sexual morality and gay liberation. A theme that comes out, especially at the end, is Martel’s examination of the Church hierarchy and the society of priests as a specifically gay culture. The Epilogue briefly lays out Martel’s analysis, and it does so sympathetically and movingly. I hope he expands on it.

I’ve tried to frame In the Closet of the Vatican as a whole, partly so that I could make sense of the symposium Luigi Gioia and I have organized. Formal aspects of the work invite critical engagement, including the methodology, theoretical apparatus, and object of study. Methodologically, does it work as a piece of investigative journalism? What is the underlying social theory, and what should we make of it? Objectively, does such a system or pattern exist? What would it mean to describe it accurately? This raises further questions about Martel’s execution: his decision to include salacious details, to make insinuations, to joke, and even to jab. Is the rhetoric befitting of the topic? For example, was it really necessary to portray Cardinal Burke as a Liturgy Queen? It’s also possible, as some already have, to engage the book’s motives and speculate about its intended and unintended consequences: is Martel trying to help Francis? Will it backfire? Might it distract from clergy abuse or be weaponized to scapegoat gay priests? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it’s worth engaging the central, substantive theme directly. As Maeve Heaney’s essay aptly summarizes: “the paradoxical and duplicitous stance between rigid morality and obsession with sex that emerges from repressed, unaware, or unintegrated human sexuality; and how destructive this is when pervasive in” the church’s leadership. This invites engagement from both psychology and from theology.

The following symposium will eventually consist of 11 essays by scholars and practitioner, who engage the book from a variety of disciplinary perspectives: sociological (Guhin), journalistic (O’Laughlin and Martin), pastoral (Martin, Gioia, and Alison), psychological (Hayward), moral (Ford), ecclesiological (Flanagan), and various other theological (Heaney, LaCouter, and me) perspectives. Each wrote in response to our fairly open-ended invitation. Though the panel is far from exhaustive or representative, we have tried to begin a responsible conversation about the book in some of the ways we think are important. Various constraints on the organization of this symposium, it will depart from the typical Syndicate format in a number of ways. The essays will initially be posted without responses. Martel’s responses will be posted as they are received. Rather than releasing the essays on a regular weekly or semi-weekly schedule, I will post the essays as I receive them.

Two unenumerated rules are also worth mentioning. “If you want to integrate with the Vatican, adhere to a code, which consists of tolerating the homosexuality of priests and bishops, enjoying it if appropriate, but keeping it secret in all cases. Tolerance went with discretion. And like Al Pacino in The Godfather, you must never criticize or leave your ‘family’. ‘Don’t ever take sides against the family’” (5). A second is related: “Everybody looks out for each other” (466).↩

2.20.19 |

Response

Facts and Fictions about Gay Priests, Bishops, and Cardinals

Over the past 20 years, I have reported on the phenomenon of gay priests in the Catholic church, but mainly in the United States.

In the Closet of the Vatican is a reminder that the experience of gay priests may differ from place to place. For I have limited experience with the Vatican, never having lived in Rome and having visited only a handful of times in my Jesuit life. Frédéric Martel’s book purports to reveal a dark side to the church, specifically that many priests, bishops and cardinals living and working in the Vatican who (according to his research) are not only gay, but also sexually active. His thesis, which he states in the introduction, goes deeper: “The more homophobic a priest is, the greater chance that he will be homosexual” (xiv).

The rest of his 600-page book attempts to support that conclusion. He strives to do so with an impressive amount of research: interviews with 1,500 people–including 41 cardinals, 52 bishops, 45 apostolic nuncios and 200 Catholic priests and seminarians, mainly in the Vatican.

His book attempts to paint a picture of a louche, licentious and libertine culture populated by sexually active priests, bishops who frequent male prostitutes and cardinals who attempt to cover up their unchastity in ruthless ways. At the top of this ecclesiastical pyramid are the various popes from Paul VI to Francis, who are, according to the book, either clueless or unwitting participants in this culture. The organizing principle of this wide-ranging but often maddeningly diffuse book is to investigate the cultures under each pope from Paul VI to Francis (though, oddly, not in order).

Early on M. Martel says that his book is not about what he calls “the American practice of ‘naming and shaming’” (xii). Nor is he interested, he asserts, in what he attributes to one group of clerics: “Old cardinals live only on tittle-tattle and denigration” (6).

Yet what prevents his book from presenting a convincing portrait of a decadent culture, despite four years of research, is precisely that. Essentially, it is a book largely about naming and shaming, tittle-tattle and denigration, both of groups and, especially, individuals. To wit:

The Order of Malta? “A mad den of gaiety” (24). The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre? “An army of horse-riding queens” (40). Cardinal Raymond Burke, who is the subject of the author’s special ire: “A Viking bride!” (27). Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò is a “drama queen” (50). Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo is a “tacky apostle” (288). St. John Paul II? A man “of great vanity and misogyny” (247).

Much of what he says about the gay subculture in the Vatican may be true. Even if a tenth of the book is accurate, it would be awful: the worst perhaps being his description of a cardinal who enjoyed beating male prostitutes. (Martel’s long chapter on prostitution in Rome, with interviews with not only prostitutes but police officers, is compelling).

Yet one’s ability to rely on the narrator is fatally compromised by the style in which he writes: hard-won research buried under an ocean of gossip, innuendo and what he would call bitchiness. Martel also uses that worst of reporting techniques: imagining, guessing, hypothesizing:

“I guess that Burke is a hero to his young assistant, who must lionize him” (259). “I have a sense that the Jesuit father wants…” (57). Cardinal Gerhard Mueller places a phone call in the author’s presence and though Martel apparently does not speak German, he insinuates that the cardinal is speaking to a lover. When Martel peers into a priest’s bedroom, even his bed is suspect: “A place for a secret rendezvous?” (305). About Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI: “Did he discover a wound cauterised by chastity?” (427). But Benedict is suspect for other reasons. He likes Mozart, “the most ‘gender theory’ of all operatic composers” (430).

Another technique is his reliance on a skill not available to all reporters. “My gaydar works quite well” (42), he says often. This convinces him that Cardinal Francis Stafford is “probably not homosexual himself” (42).

Likewise, few things escape the author’s predilection for innuendo. Even the most common sign offs and salutations in letters and emails (the kind I use regularly), as when a cleric writes, “Please accept my very best wishes in Christ” are “gushing endearments” and “obsequious” (171). Cardinal Stanislaus Dziwicz, the former secretary to St. John Paul II, invites the author not into his office but into his “lair” (200). (Also, Dziwicz has, we are told, a “greedy and idolatrous eye” 204) Cardinal Zenon Grochelewski is suspect because he “shares the first name of the bisexual hero of The Abyss by Marguerite Yourcenar” (400).

Added to the innuendo are lines that are outright cruel, out of place in book purporting to be a serious work: “Laughing at Burke is almost too easy!” (26) “Is Bertone an idiot?” (455) About Pope Benedict. “But let’s not misunderstand our queenie” (432). Another man is quoted as being, simply, a “nasty old queen” (506).

Ironically, Martel, a gay man, traffics in gay stereotypes and even slurs. Pope Francis is not among detractors, he’s “among the queens” (xv). As an aside, the book has seemingly been translated by Google Translate. We read of “seminarists” rather than seminarians (35). And my favorite poorly translated (I hope) line: “To say that this document ‘was like a bomb going off’ would be a euphemism crossed with litotes!” (45).

An old trick of reviewers is to point out small flaws to distract from a conclusion with which they don’t agree. So to be fair, his book includes some important information and insights. Martel’s commentary on the Viganò “testimony” is astute: “it mixes up abusers, those who failed to intervene and those who were simply homosexual or homophile [his term for someone sympathetic to LGBT people]” (51). Likewise, his insight that when Pope Francis speaks about duplicity in the Curia, he is referring to homophobic and sexually active gay clerics may explain the force and regularity with which Francis attacks these themes.

But it is nearly impossible to separate the fact from the fiction: the gossipy tone overwhelms the reader, or at least this one.

In the end, even after 1,500 interviews, someone is absent: the faithful gay priest. But that is an oxymoron, according to Martel, because the gay priest either opts for the “closet” (which, in his view, means being repressed and/or sexually active) or “the door.” So there are only two options for the gay priest: secretly break his vows or leave the priesthood.

The idea that priests could live their vows of chastity and promises of celibacy with any peace or fidelity is absent from the book, save a few throwaway lines. Even being in favor of chastity (by which he means celibacy, since everyone is called to chastity in their own lives, married or single) is dismissed: “The most fervent advocates of chastity are therefore, of course, the most suspicious” (177). That would include, by way of a partial list, Francis of Assisi, Thérèse of Lisieux, and Mother Teresa.

According to witnesses, he says, faithful gay priests are in the “minority” (417). With this book, however, not only would you not be able to tell, for so relentless is his focus on the evils of the gay priest; but because of his book’s predilection for guesswork and innuendo, you would never be able to know.

Response

Speaking Up

Frédéric Martel’s In the Closet of the Vatican is a book that invites certain misunderstandings. At first blush it seems like a lurid exposé—a gossipy romp through the hallowed halls of the Vatican in which a self-described atheist names names and ‘outs’ various gay cardinals, bishops, and monsignori. This impression (not inconsistent with the book’s own marketing, it must be said, or Martel’s often chatty tone) has already led to various news outlets labeling it ‘explosive’, a ‘bombshell’, and ‘scandalous’. On the other hand, some worry that Martel’s carefully-investigated study of the homosexual subculture at the highest levels of Catholicism will merely play into the hands of the Church’s most reactionary elements. Clearly, as we saw in the wake of the infamous ‘Viganò testimony’ last August, there are those who will jump at the chance to blame gay priests for the Church’s ongoing abuse crisis—an association as specious as it is slanderous.

Martel, of all people, knew full well that these dangers applied when he set out to write this book more than four years ago. ‘They will try to assassssssinate you’ he recalls his Italian editor warning him when he first brought up the idea (11). Surely it was this foreknowledge that led Martel to produce what is, ultimately, a deeply researched and assiduous account drawing on 1,500 interviews, with the help of 80 researchers and collaborators in over 30 countries and featuring a web-accessible 300-page bibliography. This is largely argument-by-overkill and it’s hard to deny that Martel’s done his homework. And yet those who scour these pages looking for juicy bits of gossip are likely to leave disappointed; our intrepid narrator is often more coy than cavalier.

But then what is Martel trying to accomplish with this book? I wasn’t sure of the answer to this question until I reached the illuminating, even tender Epilogue, where Martel lays his cards on the table. He’s quick to declare that he’s ‘not Catholic [and] not even a believer’—Molière’s Dom Juan means more to him, he says, than the Gospel of John (544, 546). But then he tells the story of a brilliant young parish priest he knew as a boy growing up in traditionally Catholic Avignon. This dynamic curate, who so excited the bright young Martel’s imagination, who sparked his intellectual curiosity and broadened his cultural and artistic horizons—this same priest later died of AIDS ‘abandoned by almost everyone [and] in terrible pain.’ This priest’s homosexuality caused him to be ‘rejected by the Church – his only family – denied by his diocese and kept at arm’s length by his bishop’ (549). If intellectual doubts hadn’t chased Martel away from the Church, witnessing this betrayal would have. It’s a story that I daresay countless cradle Catholics will recognize: A good priest reduced to ash (in this case literally—AIDS victims at the time were required to be cremated) for the simple reason that he is gay.

It is not against gay priests, then, that this ‘Catholic atheist’ (547) writes his book, but, in a way, precisely on their behalf. Observing a painting of St Sebastian in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, Martel sees deep resonances: ‘This “ecstasy of pain,” the executioner and his victim mixed together, caught in a single breath, is a marvelous metaphor for homosexuality in the Vatican’ (110). It is as collaborators in a system that makes contradictions of themselves that many gay men in the Vatican are pushed either to one extreme (chasing handsome rentboys down the backstreets of Rome) or the other (repressed to the point of self-erasure). Martel’s five archetypes of gay priests (533ff.) are useful in this regard. And it is as a form of releasing the built-up pressure in this system that a number of Vatican priests are experimenting with ‘new forms of post-gay love’ (540), which Martel discusses in one of his more allusive (if in this instance too brief) digressions. Martel draws out the connection between homosexuality and homophobia at the Vatican not in order to embarrass anyone (again—this book is far less sensationalist than its press would have you believe!) but to show the various ways in which homophobia operates as a ‘discursive apparatus’ in the Church. 1

So beyond a diagnostic account, or a recent history of gay infighting at the Vatican, or an idle look at the sex lives of elderly men, this book stands as a simple public acknowledgement: there are homosexuals at the very heart of the Church. Though this fact has been (unofficially) obvious but (officially) ‘unsayable’ (x) for a long time, one wonders—will this publicity cast anything in a new light?

I’m reminded here of Agamben’s observation that power exerts itself not primarily by ‘limiting what humans can do—their potentiality—but rather their “impotentiality,” that is, what they cannot do’.2 The Church’s discourse on sexuality restricts precisely by this imposition of impotentiality—by defining homosexual behavior as an ‘objectively disordered inclination’ within an overriding heterosexual nature, the possibility of a gay Catholic becomes, strictly speaking, an ontological impossibility. And yet, as Martel’s book ably shows, gay Catholics abound, most of all at the Vatican! It’s been precisely this discrepancy that’s left so much unsaid for so many years, and by placing a stick of dynamite in this log-jam, this book, perhaps, will contribute to a more fruitful dialogue.

In this sense Martel’s timing is fortuitous. Recently, prominent pieces in both New York Magazine and the New York Times have also brought the issue of gay priests more fully to light: ‘It is not a closet, it is a cage,’ one priest tells the Times’ Elizabeth Dias. We are witnessing a parrhesiastic moment, then, when truths long kept silent are finally being spoken. The Church tends to shy away from such moments, but it shouldn’t. For if, as Simone Weil suggested, ‘attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity’, then the Church should receive all the attention of this moment gratefully, as a chance to speak more plainly and—one day—more boldly.3

Cf. Gerard Loughlin, “Catholic Homophobia” in Theology 121:3 (2018): 188-96, here 194↩

Giorgio Agamben, “On What We Can Not Do” in Nudities, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011): 43-5, here 43↩

Simone Weil, Correspondance (Lausanne: Editions l’Age d’Homme, 1982), 18↩

Response

Perspectives on the Closet

This response to Frédéric Martel’s book In the Closet of The Vatican. Power, Homosexuality, Hypocrisy will briefly address three points: how I understand the issue at stake; some potential consequences are for the Church and the world it seeks to serve, if the book’s theses are correct, and thoughts on possible ways forward, if not yet out, of such a bleak situation.

Firstly, however, historical consciousness born of twentieth century philosophy has taught us the importance of being critically aware of context when reading a text: who the author is, what interests, convictions, allegiances, or enemies they might have. Martel quite clearly identifies himself as non-practicing, a “catholic atheist” if you will. I am a practicing Catholic of a particular kind: theologian, religious, director of a Centre for theological formation and active in the theological formation of lay people and seminarians for ministry and priesthood. Therefore, I am invested in the Church whose leadership is under scrutiny, for various reasons: the relationship with God, in Christ, I find there, the cloud of witnesses to a life of service that have convinced me, and the beauty of its truth when thought is careful and courageous.

I. The Issue at Stake:

In the light of extensive interviewing over a period of four years, Martel crafts fourteen Rules of The Closet that explain “how things work”, behind the scenes in the Vatican world. He describes homosexuality in Vatican circles, not as a gay lobby, organised or otherwise, but as a “rhizome”, a plant without underground roots that multiplies into “a network of entirely decentralized, disordered relationships and liaisons, with no beginnings or limits” (479), hidden in plain sight. The point that perhaps best summarises his thesis and its most concerning consequence, can be found (ironically?) in the sixth rule: “The culture of secrecy that was needed to maintain silence about the high prevalence of homosexuality in the Church has allowed sexual abuse to be hidden and predators to act.” The issue, therefore, is not homosexuality per se, but rather the paradoxical and duplicitous stance between rigid morality and obsession with sex that emerges from repressed, unaware, or unintegrated human sexuality; and how destructive this is when pervasive in an organisation’s leadership whose sole raison d’être is to be sacramental, a “place of encounter” with God’s merciful love and truth.

This is not the space to attempt to prove or disprove the specifics of what is alleged in each case, except to say that “only the truth will set us free” (John 8:32), so we should never fear seeking clarity. It is our moral duty as human beings and believers, if such we are. The book is long, hard to read (for many reasons), at times repetitive and bit convoluted with storylines and the occasional sweeping statement that is usually later qualified. But it also quite courageous and reflects years of research. It is too important a book to dismiss, and demands our considered reflection. There are things I disagree with: the author does, not, and perhaps cannot understand the value of well lived celibacy or consecrated life. This is understandable. Sexuality is too essential an aspect of our humanity to simply ignore or pretend it is unimportant, whatever our sexual orientation. Examples of frustrated celibate lives are not hard to find, but so are the witnesses of lives dedicated to the gospel and the service of others, whose generous, courageous and prophetic work has improved the lives of millions throughout the world. And the perhaps mysterious, (rather than unnatural) call to live exclusively for God and for the need one sees through the eyes of that felt love is too essential to Christian faith to allow hypocrisy and abuse of power take it from us.

II. Implications if the Book’s Thesis is Proven Correct

Theologically, the Church’s credible witness is named as one of the “causes,” or reasons of faith. I can already see the women and men for whom this will be one final push to definitively leave the Church, or to never come close again. For those within, it may be a redemptive scandal, if the Spirit is allowed to take charge, but the fact is that vested interests and the abuse of power affect the leadership of the Church and its duty of pastoral care. That must be the focus of our scrutiny. I intuit the book will bring into question two areas of Catholic faith and teaching, for better or worse, depending on how they are received and dealt with. The first is the Magisterium’s capacity to fulfill its mission to faithfully interpret revelation and the signs of the times for those it governs. How can we trust its guidance if bias blinds or conditions perception and judgement? The second is a consequence of the first: what issues have been and still are sidelined as a result of this situation? Can or should we revisit past decisions on important issues to see if and how context and corruption compromised the promised presence of the Spirit to guide the Church “to the whole truth”?

III Ways Forward?

Ways forward is perhaps a premature title to conclude this review, because recognition of and contrition for what theology calls ‘sinful’ behaviour is an indispensable requirement to genuine change from within – “conversion”, in theological terms – and structural change is slow. But three areas come to mind as essential and urgent, in dealing with the challenges raised:

- Rethinking and teaching the Catholic theology of priesthood in the light of the Second Vatican Council’s Ecclesiology, placing it at the service of, and not above, the People of God.1

- More care in the discernment and human formation of those responding to a possible call to priesthood. In seminary programs, human formation is identified as primary and foundational to any other foundational dimension, including academic preparation and pastoral responsibilities. Accelerating the process or bypassing healthy human maturity in the need for vocations or in the hope grace will supplement what’s missing, needs to stop.[2] 2

- The inclusion of women in every space of the Church’s discernment and decision-making processes, as well as in the training and formation of priests and future leaders of ecclesial governance. This can be done without challenging Tradition as a source of doctrine or the unity of the Church, although it will be threatening for many. The book unveils quite clearly, if only as a sub-theme, that misogyny and repressed homosexuality are often happy bedfellows. There is more than one gender ideology.

Finally, three words cut through the heaviness reading this 600-page book left in me: the implicit hope of an embattled cardinal seeking change, who ends a conversation with a smile and the words: “We will win”. As a Christian whose faith helps her make sense of life and the world around, it gives me hope to remember that truth will always come out, even if too late, for some. And God will make all things new. In the end.

There is exceptional work being done in this field by theologians well equipped to facilitate and lead the shift of culture necessary for future generations of Catholics. A recent document produced by scholars of Boston college is one example of the fruits of such thought, but it is only the tip of the iceberg of what is at our disposal, if we wish to reflect upon it. Cf. Boston College Seminar on Priesthood and Ministry for the Contemporary Church “To Serve the People of God: Renewing the Conversation on Priesthood and Ministry”. Origins, CNS Commentary Service, December 27, 2018 Volume 48 Number 31. Available at https://clergy.org.au/images/pdf/To-Serve-the-People-of-God%20-%20Origins%202018.pdf↩

Again, work in this area is clear: Pastores dabo vobis, Post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation on the formation of priests in the circumstances of the present day (John Paul II, 1992): http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_25031992_pastores-dabo-vobis.html; The Gift of the Priestly Vocation: Ratio Fundamentalis Institutionis Sacerdotalis (Congregation for the Clergy, 2016): www.clerus.va/content/dam/clerus/Ratio%20Fundamentalis/The%20Gift%20of%20the%20Priestly%20Vocation.pdf↩

2.24.19 |

Response

A “Homosexual Sociology of Catholicism” that Wasn’t

Frédéric Martel is a snob. He is unapologetically judgmental of his interviewees’ varying intellectual capacities, their tastes in art, and their knowledge of “literature” (which is almost inevitably French). It’s not a crime to be a snob, of course, and it’s not even proof you’re a bad writer. Martel makes a habit of referring to Rimbaud as only “the Poet”: it’s the only capitalization he deems permissible in a book replete with holy fathers and popes. “Luckily,” he tells us, “in France we believe more in poetry than in religion.” So, I will paraphrase my own muse, Jerry Seinfeld: some of my favorite books are by snobs!

But snobs earn the right to be snobs by doing their job well. I wish I could say this book earns its author’s snobbery. There is, after all, much that is impressive about it, not least its sourcing, its many research assistants, its globe-traveling reporting. And it’s got a sexy story, even if its characters might not be most’s go-to titillation: bishops having sex, and lots of it! And gay sex! From people who don’t like gays! And exclamation points! So many exclamation points! Yet the book often fails as a work of journalism (see Michael Sean Winters’s review), and to the extent it claims itself as a work of sociology—which it often does—it fails even more extensively. It is an important book about an important topic, and it provides us with vital information and analysis, much of it insightful, wise, and carefully gathered. But much else is a gossamer gossip, a stylistic intricacy that rips at the touch.

To be clear, there’s much here that is better sourced and altogether damning, with many set pieces that work brilliantly. A chapter on gay sex workers in Rome is devastating, especially in its focus on migrants’ uneasy relationship to priests, sometimes cruel and obstreperous, sometimes just looking for someone to love. “They want to kiss you all the time,” one tells Martel about some of the priests, and my heart breaks for the sadness of it all. And despite the book’s quidnunc bravado, there’s enough hard data here to make a case for something, and that case is mostly very sad.

One of the most powerful quotes from me in this devastating book was not anything a Vatican courtier whispered about some bishop’s boyfriend or something a dogged journalist uncovered about a homophobic cardinal’s not-even-that-secret penchant for boys. What broke my heart most was this one line, part of a series of devastating interviews with Swiss guards disgusted by their continual sexual harassment by Vatican “celibates”: “Why did they agree to talk to me so freely, to the extent they are surprised by their own daring? Not out of jealousy or vanity, like some cardinal and bishops; not to help the cause, like most of my gay contacts within the Vatican. But out of disappointment, like men who have lost their illusions.”

Martel does not cite the #metoo era, yet his study of these guards gets at much the same points: powerful men take advantage of institutional inequalities such that “consenting adults” are never really consenting. Even when the cardinals and bishops are not attacking minors, they are all too often attacking the vulnerable, or protecting those who do: Swiss guards for one, and also seminarians, as demonstrated in probably the most powerful and damning section, the take-down of the hypocritical and just plain evil former President of the Pontifical Council for the Family, Alfonso Lopez Trujillo.

There’s damning stuff all over this book, especially about the company John Paul II kept, the way Ratzinger steered his ship, and the double-speak of our current Jesuit Pope. Martel treats Francis a bit too kindly—suggesting his back-and-forth on any number of issues is simply a charming Jesuitical strategy rather than a problematic incoherence. American conservatives want to know “what Francis knew when,” and I don’t think they’re unreasonable to make that demand. Yet if it appears that Francis might have been too forgiving of ideological allies, then John Paul II is guilty of much the same and to a much more dramatic degree, supporting terror in Latin America while promoting the unworthy back in Rome, all for his unceasing faith in what he must have been sure was a greater good. Or rather two greater goods, the first folded into the second: communism must end, and Poland must be a key piece of its ending. If Martel had written about whether people were gay as carefully as he wrote about how the popes were political, this would have been a much better (and a much shorter) book.

Part of the reason for the book’s length is its many (sometimes charming, often infuriating) digressions about this or that “sociological” theory of homosexuality in the Catholic Church. And while it’s true that sociology often means different things in different countries, there were many moments in the book that I would not have allowed in an undergraduate term paper, let alone in a standalone book.

First, there is the problem of what social scientists might call “generalizability.” We have data from the Vatican and various religious elites, yet we are often led to believe that these findings are generalizable to the Catholic church writ large. On what basis are we to believe that generalizability holds? To what extent are these specific cultural phenomena unique to what is, in fact, a very small space with a deep cultural importance but no necessary causal or cultural relationship to other places, cultures, and institutions within the global Catholic church?

Second, what are the other hypotheses? We are presented with a long list of “rules” about how homosexuality functions in the Vatican, and some of them seem quite plausible (they are listed above in the symposium introduction) . But a good sociologist knows to test these against competing claims, lest we simply cherry pick our data to prove ourselves right. Martel’s approach comes closest to this when he is testing a concrete claim: while his book is already gaining some notoriety for its suggestive whiffs and tentative hints, when he says something really happened (instead of saying someone else says something happened), he tries to back up the bold claim with other sources, often including court data and other government documents. And, as the acknowledgements indicate, he’s also got a big old team of lawyers. But a sociological argument is not quite the same thing as a straightforwardly falsifiable empirical claim. You need to look for other framings that could account for the data, and then show why yours is actually the most convincing.

Most of these “rules” are quite compelling as sociological hypotheses, and quite a few would make interesting books if they turned out to be right. As they exist now, however, they are supported by rumor, innuendo, and the facts that fit the crime. Martel proceeds by a sometimes-used but much-suspected method we sociologists call “snowball sampling” (that is, interviewing people who recommend similar people to interview), which is often necessary in hard-to-reach and vulnerable populations, but which raises significant questions about the representativeness of the sample to the rest of the Vatican, let alone the rest of the Catholic priesthood. We have no survey or representative interview data from, for example, the nuncios themselves to back up that most of them are homosexual (rule 11); nor do we have a rigorous list of rumors in the Vatican from which we could make claims about their origin and purpose (rule 12). For what it’s worth, much of this might well be true and the rumors and hunches and gut feelings Martel identifies are worth acknowledging and setting up as hypotheses. The best hypotheses begin as exactly these sorts of loosely-sourced hunches, precisely because they often turn out to be right! Yet they can also be wrong, and only the data can tell. And the plural of gaydar, like the plural of anecdote, is not data.

It’s also worth mentioning that there is a ridiculous and Islamophobic essentialism manifested in rule 8 that somehow imagines it is easier for a Muslim man to sell his body to Catholic priests than to find a willing woman with which he could unleash his sexual energy. This is a separate question, by the way, from whether men in communities with strong female virginity policing—Muslim or otherwise—experience first sex with other men. But these communities also tend to have straightforward access to female sex workers.

I should say, however, that I am most impressed (and basically convinced) by rule six, even if I would modify it slightly to suggest that any individual’s homosexuality is actually less relevant that an institutional culture that so resolutely hides sexual life that predatory sex gets the same kind of pass. Conservatives will most likely only find proof the gays really are the problem, yet it seems much clearer to me that the homophobia is the problem: the homophobia that drives men into the priesthood and then compels them to hide from themselves and from others what they feel for other men, and what they sometimes do with them. Proclaiming and strictly enforcing that gays are not allowed into the priesthood will only further a culture of secrets and lies, requiring even more hiding. Don’t forget that a celibate priesthood can be both full of gay men and still normatively straight, with priests allowed to share stories of dates and crushes before entering only if such stories are heterosexual. A straight priest can have a sexuality; a gay priest can have, at best, a hidden and insidious struggle.

So these priests will (and do) hide identities and desires, whether celibate or not, and by the way: Martel seems uninterested and at times insultingly incapable of understanding that one cay be gay and celibate. Yet these priests will also hide the sex, what sex they have, to be sure, but also the sex they know others are having. And it might well be the case such sex only breaks vows. But such sex might also break laws. And more importantly, it might break lives. Yet even this hypothesis, compelling as it is, is an empirical question, one covered much better in the work of Mark Jordan and other scholars of priestly sexuality, though there still remains much work to do.

And that’s my biggest frustration. For as much as this is a work of journalism, it is often not a work of empiricism. Instead, the reader meets with sweeping judgements and damning pronouncements, often based on little more than suspicion and the rigorous methodology known as gaydar. The overall tone is one of sardonic and bitchy remove: this play is narrated by an Oscar Wilde character, full of bon mots and damning wisdom, always smarter and cleverer, alone at the bar, away from the world but close enough to crack wise about it. Yet the errors and overgeneralizations in the book give us reason to doubt the old queen is really as wise as she claims to be.

That last line brings me to another important point for me to acknowledge. I’m a straight guy reading a gay man write about other gay men, and my critiques here could be read as a form of rhetorical domination, calling for a kind of code switching that might be neither necessary nor my call to make. Yet the politics of such rhetorical moves, like the politics of anything, becomes a pragmatic question, as code switchers have acknowledged to themselves for millennia. Who is Martel trying to convince and why? If this is a story, as suggested elsewhere in this symposium, of talking like a drag queen about liturgy queens, then so much the good, and it’s not my place to say anything. But if this is a story about the Vatican, mostly intended for the general population, then the rhetorical style is a distraction. Now it might well be the case that considering this rhetorical style a distraction is a mark of my (and others’) homophobia, and that a kind of gossipy camp is only derided because of our own internalized prejudices. That’s an interesting argument. However, it’s also simply a pragmatic problem: it’s hard to pull off such a big empirical and quasi-sociological project while also making a meta-claim about how we talk about social life.

Finally, I should say that I read enough French to be pretty disappointed by the translation. As just one example: Borges is described as a novelist, and I was a bit shocked that someone as snobby as Martel would have made so glaring an error: Borges is almost as famous for not having written a novel as he is for not having won the Nobel. To his credit, I checked the original French and Martel called Borges “le plus grand écrivain argentin”: it was the translator’s error alone. My worries, on this point at least, were calmed. Martel still has some things to be snobby about.

2.25.19 |

Response

“Troppo Vero”

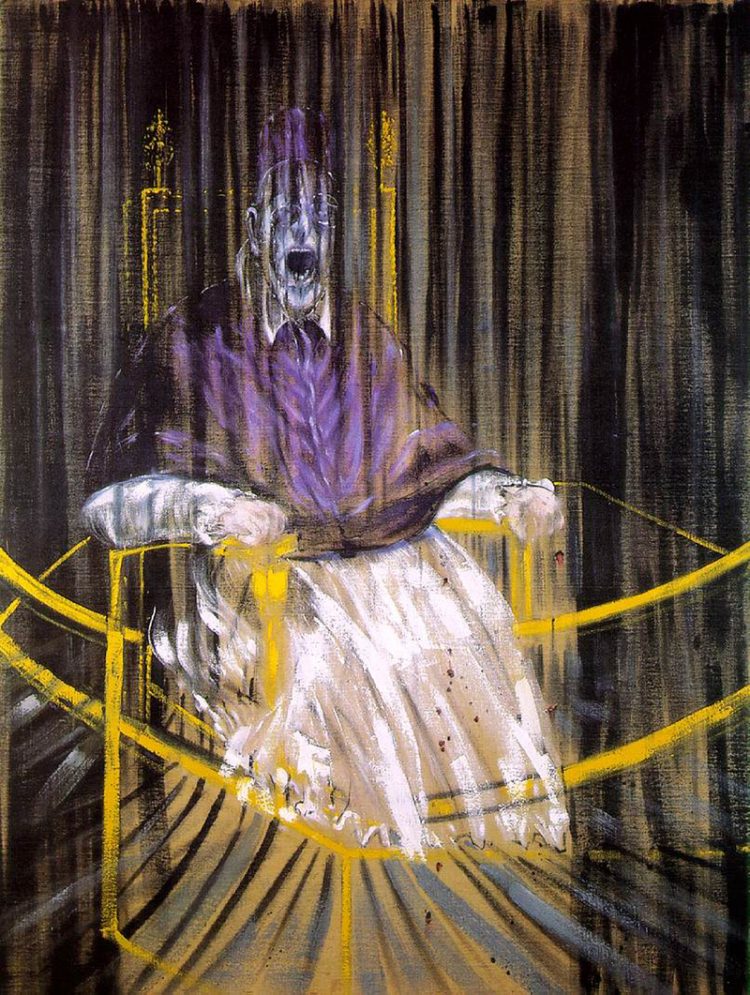

“Troppo vero.” “Too true.” Those supposedly were the words of Pope Innocent X, confronting the Velázquez portrait currently hanging at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome – the same portrait re-envisioned by Francis Bacon in the mid-twentieth century, blurred, distorted, and often screaming. In Frédéric Martel’s new book, In the Closet of the Vatican: Power, Homosexuality, Hypocrisy, the reader encounters a portrait of the Catholic Church, its leaders, and the phenomenon of gay clergy, but one is hard pressed to determine where Martel paints his picture with a hyperrealism indebted to Velázquez, and where his painting is blurred and distorted like that of Bacon. That tension, running through the book – between ugly fact and exaggerated ugliness – makes it a page-turner, and a fun, gossipy read. But as an ecclesiologist, I can observe both the beauty and the danger of Martel’s manuscript. I find deep value in this book, despite its flaws – this is the kind of book that only an astonished, skeptical, even accusatory outsider could write, and the harsh clarity of that vision may end up being a help to my church in negotiating the intersections of clerical sexuality, “the gay thing” in general (in the words of James Alison), clerical sexual abuse of minors, clericalism and clerical power, and, most significantly, a culture of lying in the Catholic Church. And yet, my deep fear is that in presenting what he has learned with inadequate precision and distorted by innuendo, hearsay, and nebulous insinuation à la Bacon, Martel has unwittingly played directly into the hands of those he most wants to challenge – those who want to identify the crisis of clerical sexual abuse as a crisis of homosexuality. Were these voices to win the argument about gay clergy, clerical formation, and same-sex sexuality, they would recreate the conditions that led to a culture of mendacity perfectly calibrated to shield and protect abuse of children and sexual harassment in the ecclesial “workplace.” My fear is that Martel’s portrait might amplify those voices in spite of his stated goals.

“Troppo vero.” “Too true.” Those supposedly were the words of Pope Innocent X, confronting the Velázquez portrait currently hanging at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome – the same portrait re-envisioned by Francis Bacon in the mid-twentieth century, blurred, distorted, and often screaming. In Frédéric Martel’s new book, In the Closet of the Vatican: Power, Homosexuality, Hypocrisy, the reader encounters a portrait of the Catholic Church, its leaders, and the phenomenon of gay clergy, but one is hard pressed to determine where Martel paints his picture with a hyperrealism indebted to Velázquez, and where his painting is blurred and distorted like that of Bacon. That tension, running through the book – between ugly fact and exaggerated ugliness – makes it a page-turner, and a fun, gossipy read. But as an ecclesiologist, I can observe both the beauty and the danger of Martel’s manuscript. I find deep value in this book, despite its flaws – this is the kind of book that only an astonished, skeptical, even accusatory outsider could write, and the harsh clarity of that vision may end up being a help to my church in negotiating the intersections of clerical sexuality, “the gay thing” in general (in the words of James Alison), clerical sexual abuse of minors, clericalism and clerical power, and, most significantly, a culture of lying in the Catholic Church. And yet, my deep fear is that in presenting what he has learned with inadequate precision and distorted by innuendo, hearsay, and nebulous insinuation à la Bacon, Martel has unwittingly played directly into the hands of those he most wants to challenge – those who want to identify the crisis of clerical sexual abuse as a crisis of homosexuality. Were these voices to win the argument about gay clergy, clerical formation, and same-sex sexuality, they would recreate the conditions that led to a culture of mendacity perfectly calibrated to shield and protect abuse of children and sexual harassment in the ecclesial “workplace.” My fear is that Martel’s portrait might amplify those voices in spite of his stated goals.

First, the ugly truth. Martel is neither a believer nor traditionally anti-clerical in the French style – he describes himself as an “atheist Catholic.” He is also a gay man who is the author of a major history of post-1968 gay liberation movements in France. These two biographical details provide the entry by which Martel was able to infiltrate – the word is not too strong – the tightly sealed world of the Vatican, and the yet more tightly sealed world of the closet within it. The book is part Bob Woodward getting the dirt from his inside sources, part Alexis de Tocqueville wandering in a strange new world, and part Page Six of the New York Post.

Many people spoke with Martel about their lives and those of others who probably regret that now. Some probably did so out of a desire to confess, as Martel suggests; others may have been naively charmed by a handsome French intellectual interested in their lives; but, I suspect, many if not most spoke with him in an attempt to weaponize their knowledge of others in the Vatican, and to use Martel as an instrument in the ongoing internecine warfare of Vatican politics. Regardless of their motives, the overall effect of the piece is astonishing, in at least three aspects. First, it provides a detailed, unflattering picture of the intrigues, plots and counter-plots, factions and shifting alliances of Vatican politics. While familiar to many Vatican journalists and scholars, the facts of how human, all too human, the day-to-day battlefield of curial politics is will be, rightly, shocking to many observers, and to many Catholics. A study of those intrigues alone might have been enough to make Martel’s research worth review.

But, second, Martel’s work suggests the inseparability of Vatican politics from the lives of gay clergy – “homosexual” or “homophile,” “practicing” or not, in Martel’s preferred terms. Martel’s contribution is to highlight the connection of the complicated dynamics of ecclesial politics with the complicated lives of gay priests, bishops, and cardinals. Viganò’s questionable “Testimony” and recent reporting by the New York Times have, along with Martel, made the wider public and the wider Catholic Church aware of a phenomenon that many of us have known for some time: that there are a large number of gay priests; some would identify as such, and some would not; some of them are celibate and some of them are not; some of those who are not celibate are, nevertheless, attempting to live lives of integrity and love; and some are very much not. None of this was surprising to me, but much of it was still shocking, particularly with regard to who, exactly, might have been doing what, with whom, and for what reasons. And third, Martel attempts to demonstrate the worldwide scope of the lives of gay clergy and of clerical sexual harassment and sexual abuse of minors (more on the dangers of conflating these three below). Within such a global scope, Martel asserts a systemic pattern; particularly for readers in the United States, Chile, or other countries marked by clerical scandal, who might only have knowledge of problems in their own backyard, Martel’s work suggests that this is not a problem of one bad egg or one bad actor, but a structural issue that the global Catholic Church will need to address. And, unlike many past studies of a particular country, a particular prelate, a particular scandal, Martel’s book has a wider scope than anything I have seen previously on the lives of gay clergy or the connections of that fact with ecclesial mistakes and corruption.

Note my language: Martel suggests, asserts, highlights – but does not prove. Martel has, in recent days, been critiqued for his reliance upon hearsay, insinuation, and anonymous sources. He does himself no favors when he repeatedly fails to resist the temptation to add one more insinuation, one more suggestive question or tenuous connection, one more piece of innuendo, to so many of his reports. In my opinion, had he, or an editor, exercised a bit more discipline and sobriety in his writing, the overall work would have been stronger. The unfortunate tenuousness of these speculations (as well as recurring small factual errors – one gets the sense that the final product was rushed to press to meet this week’s global summit on sexual abuse) makes it more likely that Martel’s work will be dismissed out of hand by some observers.

But the question remains – is it true? I am not in a position to evaluate any of the particulars of Martel’s claims, but neither, frankly, are most other readers. Like that of a journalist embedded in a wartime unit, Martel’s testimony is all we’ve got. And while the reliance upon anonymous sources, hearsay, and rumor is unfortunate, how else could he have gotten any of this information? In some ways, it stands or falls as a whole upon Martel’s truthworthiness, because the nature of the clerical closet is that the things Martel reports would almost never be admitted in public and fully on the record. Which leaves at least two major possibilities. One is that Martel is engaged in a systematic attempt to undermine the Catholic Church by constructing a conspiracy theory where no conspiracy exists. Or, alternately, he has uncovered a system of silence and sometimes corruption, previously addressed only obliquely and piecemeal, and yet pervasive in the Vatican and throughout the clerical world. Based upon the named sources who do go on the record with Martel like James Alison and Robert Mickens, upon the past work of authors like Richard Sipe and Mark Jordan, and upon my own personal, though limited experience, the latter seems far more likely. One can, and journalists and researchers should, further investigate particular details, particular charges and insinuations, and particular places where Martel’s interlocutors have misled him or where he himself has undermined his credibility through insinuation and speculation. But the overall portrait seems vero. E troppo vero.

In many ways, this is a book that could only be written by a relative outsider to the Catholic Church, precisely because it refuses some of the euphemisms and discretion that would come naturally to one inside the church. It is in many ways an uncharitable book that could only be written by someone who respects the church but has no love for the church, and no desire to protect it or its faithful from scandal. Like the child in the story, only someone like Martel could point out that the emperor has no clothes – or, more accurately, could not only full-throatedly shout that the emperor is naked, but describe in detail the not-very-appealing body thus revealed. And what drives Martel’s truth-telling? While Martel remarks repeatedly that he has no wish to judge, there is one sin that, to him, seems unforgivable or at least in need of exposure: hypocrisy. His strongest words and harshest criticism are reserved for those clergy who, while leading the charge against rights for LGBT people, same-sex marriage, and anti-discrimination laws, were sexually active with other men or turned a blind eye to the sexual activities of their associates. Martel’s book is an exposé written precisely for an age of authenticity.

In the longest of long terms, this could ironically be to the benefit of the Catholic Church. In cases of sexual abuse of minors, financial corruption, or alliances with political power, it has repeatedly been outsiders, particularly the modern press, that have been able to investigate and expose ecclesial failure and sinfulness with no holds barred. As I have written elsewhere, addressing the sinfulness of the Church clearly and forthrightly is a necessary first step for ecclesial conversion and repentance, particularly given an ecclesiology of ecclesial holiness that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries mutated into an ecclesiology of ecclesial perfection. But speaking as a Catholic theologian who does love my church, despite all its failings, I wish that we had been able to address our failings in a less embarrassing, less scandalous, and less depressing way.

Which brings me to the question of where, in my opinion, Martel’s book is most in danger of becoming a Baconian distortion, and at the same time in danger of becoming an improvised weapon in the hands of some thinkers and leaders in the Catholic Church. Given the very public equation of the problem of sexual abuse of minors with the problem of clerical homosexuality, speaking and writing about both needs to be done carefully and cautiously. The release of this book on the eve of the Vatican’s global meeting on abuse of minors, and the carelessness with which Martel slides from discussions of the abuse of minors, sexual harassment or assault, and consensual, non-abusive clerical sexual activity, mistakenly allows the three to blur in the minds of those already primed to conflate all three.

Which brings me to the question of where, in my opinion, Martel’s book is most in danger of becoming a Baconian distortion, and at the same time in danger of becoming an improvised weapon in the hands of some thinkers and leaders in the Catholic Church. Given the very public equation of the problem of sexual abuse of minors with the problem of clerical homosexuality, speaking and writing about both needs to be done carefully and cautiously. The release of this book on the eve of the Vatican’s global meeting on abuse of minors, and the carelessness with which Martel slides from discussions of the abuse of minors, sexual harassment or assault, and consensual, non-abusive clerical sexual activity, mistakenly allows the three to blur in the minds of those already primed to conflate all three.

And yet, Martel is right that there is a connection between clerical sexual abuse of minors and sexual harassment, and the unaddressed reality of homosexual or “homophile” gay clergy, and he is not the first person to notice this. The work of Richard Sipe, Mark Jordan, Donald Cozzens, and James Alison, among others, has repeatedly pointed to the overall culture of secrecy and, in Alison’s terms, mendacity that the denial of homosexuality in general and clerical homosexuality in particular has created in the church. If not one of his official “rules of Sodom,” the rule Martel gets to by Chapter 21 of his book is perhaps the key to the whole problem, and worth quoting at length:

Many of the excesses of the Church, many silences, many mysteries are explained by this simple rule of the Closet: “everybody looks out for each other” [Tout le monde se tient]. Why do the cardinals say nothing? Why do they all close their eyes? Why was Pope Benedict XVI, who knew about many sexual scandals, never brought to justice? Why did Cardinal Bertone, ruined by the attacks of Angelo Sodano, not bring out the files that he had about his enemy? Talking about others means that they may talk about you. That is the key to the omertà and the general lies of the Church. The Vatican and the Vatican closet are like Fight Club – and the first rule of Fight Club is, you don’t talk about Fight Club (466-467).

In such a culture, in which my revelation of your abuse of a child or financial mismanagement might lead you to reveal my homosexuality or sexual activity, everybody keeps their mouth shut. This is particularly true in relation to those like Theodore McCarrick or Bernard Law who wielded a great deal of power. It is an ideal environment for a sexual predator, whether he is preying upon children or upon his subordinates. And, if the alarm is raised that the problem is homosexuality in general or “gay clergy” tout court, then we as a church will recreate the very conditions that allowed the abuse of minors, the abuse of power, and all sorts of other forms of corruption to flourish. My fear is that in his blurring of these distinctions, and by the overall tone of the book, Martel may have unwittingly painted a Baconian portrait that, however rooted in reality, could be, at best, dismissed by many as the unsupported gossip of an enemy of the church or, at worst, used to justify increasingly irrational responses to a mistakenly understood situation.

I think it is too early to know whether Martel’s book will be received in the church like a pipe bomb thrown into a crowded room or whether, as in an intervention for addiction, such direct truth telling might finally lead to a more serious conversation about clerical power and sexuality, and where LGBT people fit within the Catholic Church more generally. A book of this sort would not have been my preferred vehicle for beginning or continuing this conversation. Much additional work needs to be done to separate fact from fiction, innuendo or presumption from reality, and, especially, to explain more clearly the complex relationship between the church’s teaching on same-sex sexuality, clerical homosexuality, clerical sexual activity, and clerical sexual abuse of minors. But if this work is entirely dismissed as gossip or trash, we will have missed the opportunity this text provides for greater transparency, greater authenticity, and an overdue ecclesial conversation about LGBT Catholics, including gay Catholic clergy. In a church “at the same time holy and always in need of purification” (Lumen Gentium §8) and a church just at the beginning of understanding the previously overlooked complexity of human sexuality, Martel has painted a compelling, disturbing portrait of what happens when we ignore that complexity. We dare not look away.

2.28.19 |

Response

The Complexities of Truth Telling

I found it difficult to get through Frederic Martel’s In the Closet of the Vatican. It’s long and detailed. The translation is often cumbersome. The subject matter is difficult. I took notes as I read, knowing I would be writing something about the book to introduce this symposium. But I struggled to take in everything that I was reading. Most of the book relies on the testimony of interview subjects. I believed that Martel was accurately relaying what he saw and heard in his interviews. But I am still not sure how to receive it, to categorize it, to determine its significance.

Martel has written a book about duplicity—about double lives, double talk, and double standards. It is also about the tremendous effort required to sustain duplicity and the damage that results from it. But if duplicity requires so much effort, truth telling has complexities of its own. “Truth telling is not simple,” Mark Jordan writes.

It is not like the Norman Rockwell painting in which a ruggedly handsome white man, whose plaid collar is literally blue, speaks to the town meeting at his white clapboard church, while other white men, wearing ties, listen in admiration. Truth telling isn’t like that. Truth’s speakers don’t often radiate handsome honesty. They are disconcerting and diverse rather than comfortably familiar. They are rarely received with admiring attention. And what they have to say can seem beyond hearing—or bearing.1

Jordan’s short book, Telling Truths in Church, written in response to the clergy abuse crisis of the early 2000s, points to some potential complicating factors. One is institutional context. It is difficult to tell truths about and within a church that is “old and arrogant… weighed down by institutional sins… invested in sprawling systems for keeping secrets.” The Roman church, which Jordan emphasizes is no more sinful than other churches, presents special challenges for truth telling, especially given the particularities of its size and its history. Another complicating factor: sensitivities related to the subjects of sex, homoeroticism, and homophobia. “How,” he wonders, “can we begin to talk about the institutional paradox of a church that is at once so homoerotic and so homophobic, that solicits same-sex desire, depends on it, but also denounces and punishes it?”2

Jordan’s question is striking to me in part because it is the question that drives Martel’s writing. In the Closet of the Vatican can be read as an attempt to make sense of this paradox. It seeks to break official silences precisely by uncovering the sprawling systems invested in keeping secrets. The question is also striking to me because of how Jordan frames it theologically. Journalists, he notes, typically rely most heavily on documentary truths, found in files, archives, and legal proceedings. They are “objective,” but for that reason always incomplete. Sometimes, reporters convey the truest and most important truths, the truths of traumatic memories, as they are told by victims of abuse and mistreatment. But those truths must be received for what they are—not as propositional claims, but as “the truth of an unclosed wound.” What often gets lost are the complicated truths of institutions. They are easier to glide past because of the specialized knowledge they require concerning “the regulations, customs, and fictions that enable to Roman church to operate.”3 More broadly, Jordan names the requisite expertise “theology.” I find his description compelling: “taking mature responsibility for the indispensable forms of Christian speaking.”

Responsibility has to be taken in the presence of scriptures and traditions, face to face with the ablest speaking partners, before the challenge of holiness, with a special trust (badly translated as ‘faith’). It also has to be taken through the indispensable forms. At its best, theology is not divorced from the rest of Christian speech. It is not like a superlanguage that judges every other language. Theology is more like a new grip on language, a more supple and more deliberate handling of it. The theologian takes new responsibility for speaking in the confidence that Christian speech has already been used for proclaiming a revelation, for performing sacraments, and for efficacious prayer. Language has been sanctified. We ought to be able to use it to tell sanctifying truths—which is not the same as telling ‘the whole truth and nothing but the truth.’ Taking responsibility for speech requires being especially responsible for its inevitable failures.4

Martel is not a theologian invested in taking mature responsibility for the indispensable forms of Christian speaking. He is not even a practicing Catholic. But if Jordan is right to think of theological truths as institutional truths, it would have been impossible for Martel to pursue his topic without stepping into theology. And if that’s the case, it’s not only telling the truth that isn’t easy. It’s also receiving it. I think that the categories for telling such truths are also important for those who wish to hear them well. I’ve found the categories Jordan provides helpful for interpreting Martel.

Most theologians who have wished to ask about the paradox of homoeroticism and homophobia at the heart of Catholicism (and of Christianity more generally) have written in the mode of counterargument. They have reasoned from scripture, received traditions, and official texts. Here, I think, Martel’s outsider-status helps. Theologically informed about some points, his goal is not to engage in counterargument. His book is not a plea for acceptance within the terms set by the church. This is a good thing, on Jordan’s view, because many such texts are themselves meant to induce silent conformity rather than honest engagement. Reasoning from them is doomed to be a (mostly) losing battle. Better, Jordan thinks, to engage them from a distance—exactly as Martel does throughout—using methods of media and rhetorical analysis. I think Martel can be evaluated by how well he performs his analysis on its own terms.

A second mode of theological engagement is testimony. Martel relies heavily on the testimony of both named and anonymous sources, who “come out” to Martel and reveal their double lives. Jordan exhorts his reader: “Look especially at the testimony of or about the lives of men who live closest to the exercise of institutional power, who live at the center of the institutions.” Martel recounts the testimony with the goal of discerning “the institutional arrangements and practices as they are revealed by testimony.”5 Hearing testimony well, Jordan warns, requires a sophisticated self-awareness of the inherited categories and genres for telling stories about ourselves. I think this point helps to receive the testimony Martel conveys. It is filtered through his own and his subjects’ categories and genres; both Martel and his subjects reveal themselves in what they say. This point invites critical questions about how Martel shapes the testimony and how that testimony has already been filtered to Martel. I will share some of what I noticed. I wonder if Martel has left sufficient space for the genuine theological conviction of conservatives. I think his account would have been more interesting and complete if he had. Additionally, he often relies on a triumphalist narrative about gay rights and gay marriage, borne from a progressive narrative about sexual ethics in the modern world. I think there are good reasons to be more chastened about both, not least because of how it leads him to figure those who are not so modern or progressive. I’m thinking especially of the troubling way he frames Cardinal Robert Sarah’s African tribal origins. Sarah, a convert, remains religiously primitive. He continues to share with the Coniagui tribe “their prejudices, their rites and a liking for witchcraft and witch doctors” (323). One priest Martel interviews suggests that Sarah is “literally frightening” because he “prays constantly, as if he’s under some sort of spell” (324). Martel also frames him as intellectually primitive—revealing the prejudices of his interview subjects. Sarah, he notes, is said not to “have the requisite level of linguistic understanding” to celebrate the Latin mass. One academic criticizes Sarah’s critique of Enlightenment philosophers for revealing an “archaism which places superstition over reason.” Another describes Sarah as a “bottom-of-the range theologian” and calls his theology “very puerile” (325). Martel himself engages quite painfully in such discourse when he described a “hysterical speech” Sarah gave in which “he denounced, as if he were still in his animist village, the ‘beast of the Apocalypse’” (329-330). Surely Martel could have disputed Sarah’s homophobia without accepting the premise that it reflects a primitive African identity, religion, and intellect.

A third mode of truth telling, fragmentary history, involves those truths found in archives, in tracts, in polemics, in poetry, in art and iconography. Such truths are always fragmentary because “evidence has been systematically suppressed—or never registered.” The history based on them will therefore “always be scattered and ambiguous… disorderly and incomplete.”6 Martel’s argument relies heavily on such fragments. He pays meticulous attention not only to art, literature, architecture, dress, comportment, and manner, but also to archives and texts. For example, he discerns what he calls the “Maritain Code” in French philosopher-theologian Jacques Maritain’s letters and writings. This code, he argues, is key to understanding the Vatican. More generally, his reflections on literature (especially French literature), art, and dress are often insightful and sometimes funny. I think they ought to be evaluated for how convincingly they help make his argument—both separately and cumulatively.

Jordan’s final category, provocative analogy, relies on what is known to understand what is obscure. In this case, knowledge of contemporary gay subcultures sheds light on clerical cultures. “We are particularly familiar with how contemporary American men build gay networks or neighborhoods. So, when we come to the distorted and fragmentary evidence for American clerical gayness, we bring clearer pictures for comparison.”7 Jordan offers his own work using drag queens understand Liturgy Queens as an example, which also illustrates how satire can be an especially compelling way to tell certain kinds of truths. “It would be a good thing for theologians to relearn the art of satire… Take truth wherever you find it, but also speak the truth in ways it must be spoken. Satire may be the only way to speak secrets against overwhelming efforts to hide them. Again, the homoeroticism of official Catholic life is sometimes so blatant that only powerful devices could keep us from laughing out loud at its solemn denials.”8 Martel’s work makes most sense to me through this category. He uses provocative analogies throughout his book to make what he has witnessed intelligible. That these analogies tie the argument together that comes through most clearly in the Epilogue, which outlines a series of such analogies to tie up the argument. This category also helps to explain the style and tone in which the book is written, and for which Martel has already been much criticized.

I’m sure Martel’s style—at times melodramatic, campy, catty, and even, to use James Martin’s word, “bitchy”—doesn’t prime more earnest readers to respond to his work with sobriety. But I’m not sure that’s a reason not to write that way. Irony, melodrama, and camp are not incompatible with the truth—even serious, excruciating truths. What if Martel spent 4 years doing 1500 interviews, and the best he could do to communicate what he perceived was to describe a drag performance gone horribly, tragically, culpably, devastatingly wrong? How is one supposed to address it? What form of speech befits it? Martel suggests he is reflecting how his subjects talk. But he also writes as a gay man describing his interactions with other gay men, and he uses language gay men often use when speaking about each other. And it’s not quite an insult for one gay man to refer to a group of gay men as “queens.” It might even be a term of endearment. I wonder: can a gay man like Martel tell the truth to the church? David Halperin has tried to explain why some communities of gay men talk like this:

Gay male cultural practices… tend to place their subjects, whether those subjects be gay or straight, in the position of the excluded, the disqualified, the performative, the inauthentic, the unserious, the pathetic, the melodramatic, the excessive, the artificial, the hysterical, the feminized. In this, gay culture simply acknowledges its location—the larger social situation in which gay men find themselves in straight society—as well as its unique relation to the constellation of social values attached to that society’s dominant cultural forms. 9