The Hurricane Notebook

9.27.21 |

Symposium Introduction

Philosophical Gothic: Form and Genres of The Hurricane Notebook

I.

Elizabeth M.’s writings were sent to me in the summer of 2014 by Alexander Jech, who had been looking through them over the past year. Alexander had a vision for cleaning up the manuscript well enough to be published as more than just a pile of obscurities. The task seemed monumental, but necessary—a job you can’t say no to, because you’re the only people in charge of deciding whether someone’s story lives or dies. I can honestly say that in the years we have spent working on this book, the labor has been as edifying for us as it has been constructive for the manuscript itself. Any editors of this book, it seems, needed to have been people who would change along the way—people who would change as they worked. We certainly did that.

Some advance readers of The Hurricane Notebook have wondered how to categorize the work into a literary genre. Here, I would like to introduce some clarity on this topic, or explain the lack thereof, before the book enjoys a larger readership. Straightforwardly, there is a real sense in which this manuscript transcends many genres and is not, strictly speaking, within any of them. The content seems to be nonfiction, even though some characters seem not to be obviously identifiable with existing individuals, and many of the conversations seem quite fantastical—vending machine suppliers who double as theologians, and bartenders willing to discuss Kant. So, a nonfiction genre like memoir is not, in my estimation, the correct literary genre within which we should place The Hurricane Notebook. If pressed, I would name three types of literature that the journals of Elizabeth M. can be broadly understood as exemplifying: philosophical dialogue, Southern Gothic, and Greek tragedy.

II.

Although one would be missing much if they understood this manuscript solely as serving a philosophical purpose, its function as a philosophical dialogue is undeniable. The meat of Elizabeth’s journal is the recounting of conversations with her peers, and nearly every one of these conversations is explicitly philosophical in nature. The most important themes draw on existentialist and religious philosophers such as Augustine, Pascal, Kierkegaard, and Dostoevsky, but these dialogues often tackle more wide-ranging material, including traditional philosophical figures such as Plato, Aristotle, Kant, and themes from contemporary analytic philosophy. There is a sense in which these recorded conversations strike the reader as contrived; it is difficult to imagine such a cast of philosophically adept characters as Elizabeth portrays. Additionally, one often gets the idea that Elizabeth’s interlocutors are sometimes speaking for her, and that her own recorded responses to “their” arguments are the worries and doubts with which she is plagued. Plato never placed himself within any of the dialogues he authored, and even Plato’s Socrates cannot be comfortably assumed to speak for him; Berkeley and Hume follow Plato in this practice, so that, similarly, it’s never entirely certain that Philonous and Philo speak for them. Aristotle and Cicero diverge from this pattern; they appear as characters in their own dialogues whose arguments and ideas do appear to represent the views of their authors. Elizabeth, as an author, falls in between these camps. She writes herself in as a character, yet in such a way that we cannot always be confident that the position the author takes is the view she puts into her own character’s mouth.

This may be due to a difference in function between Elizabeth’s dialogues and those of the aforementioned authors. A philosophical dialogue is a type of narrative in which argument constitutes the action, and the central conflict is a philosophical problem whose solution bears on human life. Thus, in the Socratic dialogues, ethical content predominates, and they continually feature dramatic portrayals of aporia—philosophical angst—over these questions. But an author may write in a philosophical mode either for the sake of teaching something the author has learned, or for the sake of addressing the author’s own confusion and angst. The Hurricane Notebook is a work of discovery of this latter type. Perhaps Elizabeth therefore appears in her own dialogues, then, not as a teacher of some truth she wants to give the reader, but as an illustration of her efforts to discover that truth.

III.

Perhaps the least intuitive of my three genre suggestions is Southern Gothic. This categorization is generally applied to works of fiction, but the notebook often reads so much like a novel (albeit a fragmentary one) that it is difficult to avoid making such literary comparisons. Superficially, there is much to support such a categorization. Elizabeth M. lived in, and wrote about, North Carolina, which, while far from the Deep South occupied by Capote’s and O’Connor’s characters, still retains a whiff of Southern spirit. In this way, The Hurricane Notebook is more aesthetically similar to the work of Thomas Wolfe or Toni Morrison—work that contains a bit of Southern aesthetic, but muted, or sitting awkwardly alongside a more stifling presence of Midwestern starkness. This, in some ways, gives the audience an advantage—a strong regional aesthetic, like a strong accent, makes something interesting but easy to misinterpret. In The Hurricane Notebook, unlike typical Southern Gothics, there is no theme of natural decay; rather, the characters are decaying, while the natural world around them flourishes, unbothered.

Elizabeth’s central concerns—redemption and the human capacity for evil—are paradigmatic Southern Gothic themes. Similarly type-typical is her propensity for discussing universal themes of love, guilt, and human nature, using overtly religious terminology and metaphor. Many of her questions—in fact, her deepest questions—are religious in nature, and her search for penance and redemption, while not confidently Christian, is no secular journey. Here we might make a comparison to writers like Walker Percy, John Updike, perhaps even Flannery O’Connor (though O’Connor’s writing differs from Elizabeth M.’s in most other ways). But while fascinated with God and evil, the writing in the notebook is not what one could call orthodox Christianity; it is haunted by these ideas but reflects a spirit uncertain of how to approach them. Elizabeth was heavily influenced by existentialist philosophy and themes of absurdism, and in these ways carries on the torch of Sherwood Anderson and Cormac McCarthy.

The characters of The Hurricane Notebook with whom Elizabeth discusses these ideas are likely the most obvious markers of the Southern Gothic nature of the work. Unlike her depiction of her sister, Sarah, or her friend, Joshua, Elizabeth’s portrayal of her interlocutors—coworkers, college acquaintances, mysterious strangers—are essentially one dimensional. Among those she debates, only her old mentor, Simon, to a degree, marks a partial exception. Her primary interest in keeping a record of these interactions seems to clearly be the ideas discussed therein. The result is that these characters are, for the reader, reduced to a single idea. If there were real individuals behind these characters, they seem to have disappeared into the single thought that Elizabeth associated with their persons. This is one of the primary identifying features of Gothic literature—featuring “grotesques” to keep the reader uneasy. Unlike a typical Gothic, however, our protagonist does not become more distorted, more grotesque, as the story goes on. Instead, the notebook conveys her attempt to arrest her own movement toward grotesquery.

IV.

However, what struck me initially about The Hurricane Notebook, once all the pages were in order and all the shorthand translated, was that it has a very classical structure. In particular, the journals can be read like a Greek tragedy, in which guilt and fate are discovered together. That is, the reader knows of the terrible event that has occurred in Elizabeth’s life, and it’s clear early on from the entries that she is suffering with a sort of depression; yet, beyond these relative superficialities, Elizabeth does not, initially, actually write very much about the event. And so, the impact of the death on Elizabeth is slowly revealed to readers of the journals as Elizabeth acquires greater understanding of life, relationships, and human nature. It is not hard to imagine that this tragic structure was, if not intentional, a natural subconscious effect of her immersion in the classical world. Elizabeth knew Greek and Latin, she knew the great tragedies and comedies, she knew Greek and Roman philosophy; she was already thinking like an Ancient, and no doubt her writing naturally followed suit. It may, in fact, have been intentional—a sort of device for framing her musings, to aid her own investigations into these deep philosophical questions.

For an interesting literary comparison, one might look at Donna Tartt’s inaugural novel The Secret History (1992). Like The Hurricane Notebook, Tartt’s book also has an overtly tragic structure, but in this case expertly transposed into the form of a modern novel—a structure made even more obvious by the fact that the story focuses on a small group of young classics students who meet in Greek class. Also like Elizabeth’s journals, Tartt’s novel focuses largely on the post-tragedy condition of this group of students, especially on their guilt and the subsequent personal unraveling occasioned by this guilt. Despite these similarities, it should be noted that we have no reason to believe Elizabeth M. ever read The Secret History. Throughout her journals Elizabeth M. refers to almost no contemporary literature, preferring to get her fill of fiction from the classics, and such a story of sin and undoing would surely have been mentioned by our author at least once somewhere in her writings.

One obvious, and important, difference between The Hurricane Notebook and The Secret History is the trajectories of the characters. In Tartt’s novel, guilt is shoved under the furniture, and the result is the eventual rotting, a dissolving into something near irredeemable, of each of the main characters. Elizabeth M.’s journals show no sign of such evasive maneuvers; indeed, our mysterious writer forcefully and repeatedly commands herself to face her guilt (or what she believes to be her guilt) honestly—“No lies.” The results of these diametrically opposed responses to terrible guilt are equally opposed outcomes. Unlike Oedipus, she refuses to take her eyes out, and forces herself to see the truth she had suppressed so long. Rather than rotting from the inside out—an ending typical of a classical tragedy—Elizabeth experiences deep intellectual and spiritual growth, even as she walks close to, or perhaps even dances with, madness.

V.

Some readers, after having read The Hurricane Notebook, may want to make a case for other genres. I do not take myself to have covered all, or even most, of the important literary elements of Elizabeth M.’s writings. It is clear, however, that the writings were intended to be a record, not a masterpiece or authoritative statement. It also seems—evidenced by the stylistic changes that progress over the course of the book—that this manuscript was possibly written over the course of years. Such evolutions of style add yet another layer of difficulty when it comes to genre categorization. What begins as almost straightforwardly a philosophical novel is soon punctuated with mysterious letters, ruminations about her friend and sister, flashbacks, poetry, and the slow burn of deepening anxiety. By the end of the manuscript, scenes come at us quickly in the form of four-page chapters seemingly disconnected from the primary narrative. But the connection is, of course, Elizabeth herself. The Hurricane Notebook, ultimately, is a record of an individual trying to pull all the experiences of her life into a story that makes sense to her. And maybe there is not yet a genre for a work like that. Maybe this is the first of a new genre.

10.4.21 |

Response

Self-Making Passion, Betrayal, and Recovery

A Personal Response to The Hurricane Notebook

I. Three Aspects of an Infinite Pathos

The Hurricane Notebook, which I will abbreviate HN, is a remarkable work on several levels, including its vivid attempts to illustrate and explain central Christian ideas concerning sin and redemption. The story of the fishes in the “Matin Sea” sticks with me the most. But I could never do justice to these aspects of “Elizabeth’s” narratives, edited by Alex Jech, or even adequately discuss the Kierkegaardian and Dostoevskian themes found throughout. So I will focus more specifically on the ideas of “self-making passion,” crisis, and hatred, especially as described in a letter that Elizabeth receives from one “Niakani”—an unknown correspondent whose points challenge some of Elizabeth’s principles (9).

These themes run throughout HN, because Sarah has despaired due to some perceived betrayal by Elizabeth, and Elizabeth hopes to find in Niakani’s letter a diagnosis of what went wrong (10). This betrayal of her sister, apparently through total contempt for her lifestyle (or refused empathy), is the sin from which Elizabeth cannot recover. Her recognition of this is a crisis that makes wholeness in personality and purpose unreachable, but apparently not because she devoted herself to something incompatible with her facticity—the “historical, biological, and social” factors in personal identity, including temperament and aptitudes (94). In fact, Elizabeth seems remarkably suited for her philosophical work, and for dance at least as a hobby. Rather, her crisis is due to having caused Sarah’s crisis by refusing to love her, or failing when she was in a unique position to help Sarah through her crisis (148).

Niakani is right, I think, that people need a self-making or “infinite” passion to give overall direction to their identity, or an overall orientation that integrates their concerns (97). Without such a passion, people can muddle on, but always with a suppressed sense of stuntedness or incompleteness that gnaws at whatever sense of meaning they have found. A self-making passion has three conditions according to his explanations.

(1) It involves being “opened” to the world by finding persons, places, or things worth loving for their own sake. The young lad’s devotion to his princess in Fear and Trembling is a ready example: Kierkegaard (Silentio) calls this an infinite pathos because it concentrates the lad’s soul. Christianly understood, these calling are “God’s intermediary to us” (98–99). Goods worth treasuring are disclosed, and we are revealed to ourselves in discovering them, starting to care about them, and eventually committing ourselves to them. This explains why mystic transport out of this world is not the solution. The fishes may peek above the water, but they are meant mainly to focus on the world within their sea; trying to live forever on the surface is neglectful (171–72). This world is not a mere cave to be transcended, even if its design was somehow marred against its creator’s will (as some stories say); it has inherent values waiting to be transfigured or shown in their true light.

(2) But to be adequate, a self-making passion must not ignore important elements of our selves (96), even if they are inconvenient in some respects, e.g., if they are potentially unpopular perhaps even shocking to others. These “rogue” elements (as I will call them) might be potential talents, or nascent interests, or basic psychic tendencies that are already within us before “opening” to related aspects of the world calls them forth in concrete ways. Or they might involve bodily or historical facts, such as an unusual physical difference or a disturbing family legacy that calls for response (and all of the above may pertain to Kierkegaard’s fear of marriage, although it was a mistake to break his engagement).

I am going beyond what the text says here, but these seem like plausible extrapolations. Such elements seem “rogue” because they can make us feel out of place in our assigned groups, as when Ferdinand the Bull loves flowers. Or they can make us feel out of place with ourselves, because are especially hard to understand, or to square with other aspects of our lives. But they have to be worked into the volitional cord that synthesizes our motives (123). Rogue elements are distinct from some psychic inclinations or tendencies that are simply harmful and should be opposed (e.g., some kind of appetite for gratuitous violence). Instead, rogue elements can contribute something; when cultivated, they may attune us to values that significant others overlook. Thus the romantic notion that a private vision or inner inspiration may be worth devotion (179). As Martin Buber said, the thou that calls uniquely to me may be an idea given for me to embody; in that case, devotion to it is not mere narcissism.

(3) Still, despite its concrete devotion to particular goods, Niakani’s infinite or self-making passion has a regulative role. By definition then, we can have (at most) one of these at a time, because it must inform and help govern our other emotional responses and willed devotions, even while they are responding to values and facts in the world outside the self. An infinite passion

[EXT]possesses the power to define, shape, or realign every aspect of the person, thereby giving a single concrete form to the person’s will and inner being. It assigns other passions their function, direction, and meaning, and they allow it the right to condition their role within the individual’s overall life. It gets into everything the person is and draws this together into a combination that makes sense. It holds this dynamic power at all times, and so it is a power whereby a person can attain unity. (97)[/EXT]

This way of qualifying all other pursuits and concerns makes the unconditional concern (Tillich’s term) more like the basis for “purity of heart” in Kierkegaard’s sense. But the more robust we make this regulative role, the more the object of one’s infinite pathos must itself take on infinite value, as distinct from the combination of earthly goods that it is our task to love, in our own unique way. Otherwise the object of infinite pathos cannot adequately support its regulative power.

In short, there is a tension between Niakani’s conditions. If purity of heart can be sustained only in willing “the Good,” as Kierkegaard put it (in his Socratic “religiousness A” terms),

The HN rightly rejects this solution (97, 179–80), but that still leaves us with the problem that right infinite passion, i.e., one that is right for us individually, must still be able to point a way forward when the more particular objects or subjects of our devotions collapse or become inaccessible—which can happen for a host of possible reasons. How can we love Beatrice herself, not just something else that she symbolizes, and yet, within devotion to her for her own sake, also love “the figure of Beatrice”? In other words, how can we remain true to what was worthy in the actual Beatrice when she has permanently gone from us, or has even rejected us? Although she is unique and irreplaceable,

II. The Crisis, Existential Luck, and Modes of Recovery

Obviously this brings us to Niakani’s worry about the crisis. Without the “interconnection with being” or openness, we are curved in on ourselves in sin. To love, and thus to become a self in the full sense, we must allow this relation to specific persons and goals to establish our identity through a “pattern” that will run throughout our participation in the “pageant of life” (101–2), a description I really like. But this requires risk of existential unraveling or collapse (106). Elizabeth imagines Gilgamesh betrayed by an inauthentic Enkidu, or Plato betrayed by a false Socrates; and Christ was surely wounded more by Peter’s denial than by the spear. In this crisis, all sorts of other possible devotions seem viable, when before they were almost “unthinkable” in Harry Frankfurt’s sense. Infinite hatred is one possible response, when the victim focuses on the harm done to her or his self (107), likely with vengeance as a new purpose. The Henri Delacroix case suggests that this can happen even without long-nurtured malice (129).

The challenge here is that the crisis so understood implies that the self-forming passion that was right for a particular individual—without which she cannot be true to significant callings and given aspects of himself—can be destroyed by contingencies ranging from death to misunderstanding and faithlessness, including his own betrayal of another (especially if that drives her into crisis). Call this existential luck. No doubt there are large quantities of existential luck in variations across persons: some just have a much easier set of ingredients to “cook up,” while others have more unusual callings and more recalcitrant rogue elements to develop in some positive way. However, if there were only one type of pattern or infinite passion that fits us, and it could be destroyed by contingencies, then human persons would be subject to more radical existential luck. That is different than our pattern being sinfully destroyed by defiant refusal to love rightly, or to accept given vocations, until it is too late (99). Even if the sense of “original sin” implies paradoxically that such defiance is inevitable despite being free, that is distinct from radical existential luck.

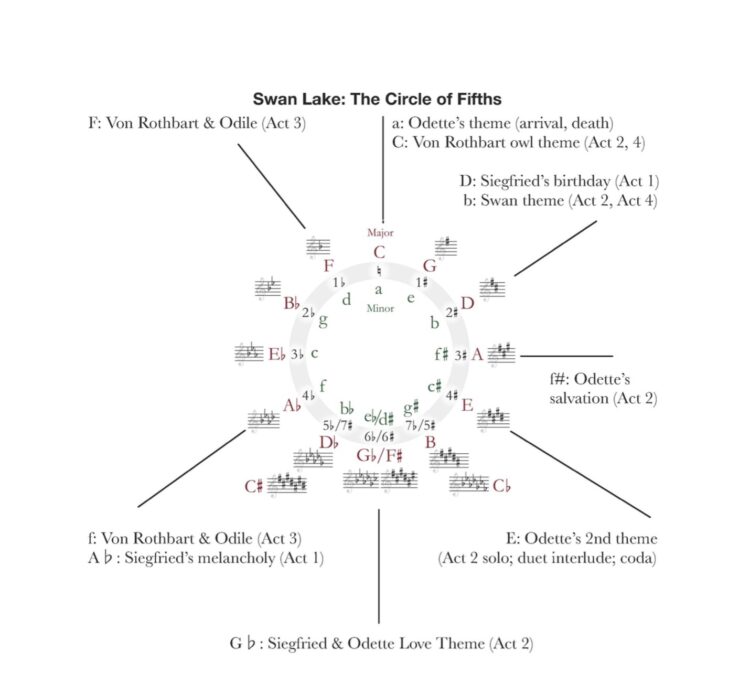

The problem, in short, is that Niakani misconstrues self-making love/devotion as an absolute bond to a particular person or calling. Thus a Plato betrayed by Socrates has nothing else to fall back on: Socrates runs throughout his identity (105). The betrayed one may respond with infinite malice because he “had already allowed her [his betrayer] to define every aspect of himself” (111). Thus Simon’s reaction that Niakani’s “self-making passion” only makes the problem of sin worse: if he betrays his beloved or is betrayed by her, that wrong comes to define everything in him (126). Then of course Henri Delacroix must be completely destroyed by his wife’s perceived betrayal (131). This is the inevitable conclusion if we are defined by a devotion to Beatrice so total that it excludes the “figure” that she imperfectly embodied. Elizabeth’s own dark conclusion from Swan Lake that human love is “our way of trapping each other” into an identity that must destroy us is, I think, a symptom of Niakani’s error (210–13).

To avoid this repugnant conclusion, we have to envision ways that the individual can restore himself with a new self-forming pathos that remains true to enough strands of his previous pattern. Not without loss, as I have conceded, for then the love that was betrayed or fruitless would not have been real; much in the new pattern may still remind him of what was lost. Nor do I mean that the individual can do this all by herself, without any help from others or from God; but that qualifier applies to forming the first infinite passion as well.

First, the victim might consider whether they were mistaken or misinterpreted; Othello, for example, was manipulated into believing that he was betrayed. A little more humility and trust in his beloved might have saved him. Similarly, even if he were certain about his wife’s affair, did Delacroix consider that maybe she was under duress, maybe the other man was even threatening his family? Human beings are not God, and we cannot trust in them against all evidence without limit. But sometimes great humility is needed.

Second, even if the perceived offense is real, there is always the possibility that it was more justified than the victim recognizes. Although Elizabeth badly erred, did Sarah recognize any fault on her own side? In The Scarlet Letter, Chillingworth views Hester as totally in the wrong, and his response is precisely the infinite hatred described in HN (107). And yet, as flawed as Hester may be, it was really he who abandoned her. Similarly, Saliari in the movie Amadeus is clearly wrong to think that God has betrayed him by ruining his self-defining passion for music. He becomes a “Knight of Malice” in Niakani’s sense, hating being as a whole (113), when he could have remained true to what was right in his career as a composer by aiding Mozart and training new musicians. But he resisted such a humble reinterpretation of his calling, and insisted on interpreting it only in a greatness-focused way that was “betrayed” by Mozart’s arrival.

As this illustrates, sometimes even a rebuke or rejection that forces us from the path that guided our journey may communicate precisely what we most need to learn. Recognizing this also opens a way of covering a multitude of others’ sins that is consonant with Myshkin’s recognition of complexity in people’s motives (109). Although we are sometimes genuinely innocent, as Job insisted, we always have more to learn. From a providential view, one’s truest calling may be very hard to discern rightly; and there may be more than one self-making passion that could integrate us, with all our flaws. The guiding pattern that is best for us might only be discoverable in the wake of tragic failure or deep betrayal (by others or by ourselves).

We must be careful not to be satisfied with solutions that are too easy or dismissive here. Existential luck is real, and betrayal can shock a person to their core. Imagine that the heir to a throne who prepared all his life for devotion as head of state discovers that he is a changeling substituted in by his “parents” when their original son died in an accident. The total spiritual vertigo that would ensue, as his whole conception of his place in the social fabric is turned upside down, would approximate to the infinite self-doubt that Niakani describes (105). Recovery in such a case will certainly require a lifeline, or hesed, from others.

Yet the crisis need not refute the person’s most central purpose or the deepest values underlying that purpose. In the movie Braveheart, when William Wallace discovers that Robert Bruce has secretly joined King Edward I’s attack on Scotland, he is cut to the quick, unmoored. But his calling to free Scotland cannot refuted by this cruelest stroke. This is an example of remaining true to the principle in our infinite pathos even through a crisis.

In such recoveries, love from a human person, like Myshkin’s, can be enormously helpful, especially if the collapse of our self-defining project is not (mainly) our fault. But what if the betrayal was our own: what if, when the chips were down, we violated our own deepest commitments? Here too, an impression that this is so can be mistaken. The hero of Ordinary People needs to learn that he was not really at fault for his brother’s death. In Sophie’s Choice, Sophie is also not at fault. And yet one can understand, and even agree with, Sophie’s collapse. For she has come in contact with an evil so enormous, so infinite in both reach and depth of malice, that no recovery might be imaginable without some higher level of grace. This is the most painful of examples, in which the betrayals of others force one to (seemingly) betray oneself. I do not attempt to answer the challenge posed by this case; for me, it encapsulates a grief for all humanity, a sorrow like the girl’s at Matin Lake, deeper than the well of the worlds.

Third, even when staring into the abyss of one’s dreams or the evaporation of hopes through betrayals, the discovery of new goods itself may be able to provide an unexpected ladder. Although this sounds like luck or grace, maybe this possibility is always somewhat accessible, because our self-making passion can never encompass the fecundity of this world and it creatures within it (as Myshkin’s view of nature, which is also found in the Brothers Karamazov, suggests—91). The best literary exploration of this theme that I know is found in Stephen Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, to which I turn next.

III. Covenant’s Crisis and Recovery

Donaldson’s first Chronicles is an epic fantasy trilogy that rivals Tolkien’s in depth with more Dostoevskyian vision.

When Covenant enters the fantasy realm—not through a wardrobe but instead through an accident that knocks him unconscious—he awakens in a world in which all the values that Myshkin perceives are tangible to everyone who has been touched by the power that runs through this Land. But he diagnoses these “cleansed doors of perception” (Blake) as easy escapism, because he does not trust himself: he insists that this must be a wish-fulfillment dream. Betrayed by life and spouse, he thus betrays the world that offers him friendship and reverence: he rapes Lena, the young woman who personifies the Land’s goodness and its covenantal offer to him.

This crime has a cosmic significance in Donaldson’s narrative, and it is Covenant’s personal nadir. But although the crime cannot be undone, the Land is full of grace; while the young woman’s parents are unable to avoid self-consuming hatred in response, many others still believe in Covenant, by “virtue of the absurd,” it seems. Bit by bit, this irenic support allows him to face the reality of what he has done: whether Lena is merely a dream or not, rape is a mortal evil.

After recognizing his crime, Covenant is still too afraid, too broken by his wife’s and his own faithlessness, to devote himself to the Land’s defense.

So Covenant keeps looking for others onto whom he can shift his responsibility to redeem the Land from the doom gathering around it. In particular, he helps his own daughter, Elena, reach a power that she believes might destroy the Land’s demonic enemy. He eventually realizes that this is a betrayal which imperils her, and repents it at the last moment, trying to get her to withdraw. But he is too late: she is determined to use this power. Its destructive results are a further ramification of the evil embodied in the rape.

In the wake of her death, Covenant finally accepts full responsibility. Although he is unravelling, he is able to muster enough strength to save a little girl in our world who has been bitten by a rattlesnake. Mhoram attempts to call Covenant back into the Land just as he is trying to help this girl (a minute in our time is correlated with many weeks in the Land’s time). But Mhoram hears Covenant’s appeal and lets him go,

Clearly Donaldson’s themes are Dostoevsky’s, and Niakani’s.

“Something there is in beauty, which grows in the soul of the beholder, like a flower,” Lena sings when he first enters the Land. While the beauty may die, or the whole world may die, “the soul in which the flower lives survives.”

On the whole, Donaldson’s story is about as good a case for restorative justice as one could make. Beyond this interesting civic application, it is an argument that existential luck is not the sole determinant. Even when the crisis is not (entirely) of our own making, there is a way through it. Covenant is willing to try faith where Kierkegaard could not (or would not) risk his beloved and/or his vocation as a writer. He opens to love and life again.

Of course, sometimes recovery barely has a chance to begin, because the betrayal leaves the victim with no adequate response but to lay down her or his life rather soon afterwards. As I have introduced fantasy examples, let us envision a different ending to Frodo and Sam’s tale in The Lord of the Rings—arguably the ending towards which the narrative development really points. Gollum’s final act of taking the ring and accidentally falling into the fire of Doom is motivated with many foreshadowings throughout the text, and it is the sign of grace. But the story would be even better if Sam had formed a resolute response to Frodo’s great “betrayal.”

In conclusion, HN is right about existential crisis and its spiritual dangers. However, the kind of infinite passion needed to fully integrate a self is compatible with recovery from the crisis, because, beyond the finite goods to which it opens us, it also orients us towards infinite goods that govern how we should pursue the finite ones. Even when Lena is lost, the figure of Lena and her flower survives.

All my references to the Hurricane Notebook are given by parenthetical page numbers.↩

Buber, I and Thou, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Scribner, 1970), 60–61, 83–84, 130 on divine vocation.↩

See Soren Kierkegaard, “On the Occasion of a Confession,” in Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, trans. Howard A. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton University Press1993).↩

While Plato missed this nonfungibility of the beloved, Kierkegaard recognized it: Regine could never merely be his “muse.” His mistake was to imagine that he had to choose between Regine and “the figure of Regine.”↩

This is similar to the problem of narrative continuity through radical character-change and related questions about penance and redemption (184–86). The response to the crisis that I am defending here is anticipated in my Narrative Identity, Autonomy, and Mortality (Routledge, 2011), 124–27, 146.↩

Very likely I cannot articulate recovery for Sophie because for me, this case has come to embody something central to my own self-making pathos, which must always have some roots that are obscure to us.↩

Stephen Donaldson, Lord Foul’s Bane, The Illearth War, and The Power That Preserves (Ballantine, 1977–79). I cited the one-volume paperback reprint, The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant (HarperCollins, 1996). There is a second trilogy and also a third series of four books (The Last Chronicles of Thomas Covenant), which I do not discuss here.↩

Donaldson, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, 293–302.↩

Donaldson, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, 760–68.↩

Donaldson, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, 828–29.↩

Donaldson’s story also draws many mythic motifs from Wagner as well, but for purposes entirely the opposite of Nietzsche’s.↩

Donaldson, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, 1006–9.↩

Donaldson, Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, 57–58.↩

I use the quotes because Frodo’s act is technically a choice, yet it is also meant to be a foregone conclusion for mortal beings (because it represents original sin).↩

10.11.21 |

Response

Why We Write (and Why It Matters that We Do)

When you think about it, that human beings have developed the written word is actually a strange fact. Socrates was famously opposed to the idea of written philosophy because it didn’t allow for the spontaneity required of truth seeking—namely, we need to be able to change our views in light of new evidence and arguments. For Socrates, writing problematically stabilized one’s position in ways that actually eliminated the possibility of further thought. And yet, it is only because Plato (and a few others) wrote about Socrates that we have a record of his critical view of philosophical writing.

Though I am glad that Plato didn’t listen very well to his teacher on this particular point, I also think that Socrates is probably right about the dangers of writing. Kierkegaard says somewhere that life is the moment of decision. I love that description of the lived condition. We are always, at every moment, navigating the world in order constantly to become who we will end up having been. Yet, whatever we write will only stand as a reflection of a particular moment in that becoming. In this way, writing seems to function the way that photographs did prior to the new technology that allows you to hold down a picture and see a few seconds of video on either side of the image that has been captured. Like pictures, no written text will ever be adequate to the lived experience itself. Life is fundamentally excessive, and attempts to domesticate it so that it is easily framed (whether by some strips of wood to hang on the wall, or by front cover art and back cover endorsements) are bound to meet with difficulty.

And yet we write. What might this say about us as the peculiar sorts of beings that we are? I think that it speaks to our fundamental vulnerability. If we were immortals, then we could always write our great book . . . tomorrow.

But we are not immortals.

I think we write because it is the closest thing that we have to permanence in light of essential existential contingency. I think we write because it is what invites others to know that we existed. From “Aaron was here” crudely carved into a desk or a tree, to multivolume academic treatises, writing is a way of making an impact that will hopefully outlast us. Interestingly, though, I don’t think it is primarily about our words living after we pass away, but about us leaving a particular narrative of who it is that we were. We write in order to become authors of our own lives.

I love that line in the movie about C. S. Lewis, Shadowlands, where Lewis comments “We write in order to know that we are not alone.” This idea gets it exactly right. If we were alone, then we would not feel the need or have the desire to try to tell our stories (much less to tell them in particular ways). Writing is a historical phenomenon reserved exclusively for relational beings. The same is true of reading—by definition, really. We read in order to know that others have existed and that it mattered that they did. This realization gives us hope that our lives might also be worth something—worth being read about by others. Importantly, when we read we are not just learning about others, but learning to care about ourselves in the right sorts of ways. As Anne Lamott says in her book about writing, Bird by Bird, “writing motivates you to look closely at life, at life as it lurches by and tramps around” (xii). As she goes on to explain, reading and writing teaches us to pay attention.

David Foster Wallace would likely remind us at this point that we are always paying attention to something, but the problem is that we rarely own up to the fact that we are responsible to choose wisely about what is really worthy of our attention. In other words, there are so very many stories to be read, so very many events to be witnessed, so very many conversations to be had, so very many values to be held, so very many words to be used. Writing is hard work because it requires us to be intentional about all of this. Reading is hard work because it requires us to develop patience in relation to the intentionality of others who decided to write what they did.

So perhaps we do read so that we know that we are not alone, but so too we write so that we can figure out what we think, what we believe, what we value, and why it matters that we do. Simply put, I think we write so that we can figure out who it is that we want to be. We write to introduce ourselves to others after first meeting ourselves in the words that we write.

In The Hurricane Notebook, we are introduced to Elizabeth M., a young woman who is struggling to find herself, having lost her sister, Sarah. Not having accomplished anything truly significant (in the culturally normative sense of the term), not having done anything really distinctive, not having experienced anything all that unique, not being anyone really all that worthy of our attention, Elizabeth M. ends up being radically singular precisely in that she is universally interchangeable.

She is us.

I am her.

Perhaps that is why her story is so valuable. She took the time to write about the conversations that she had because they were the opportunities for her to come to figure out where she stood—about God, evil, providence, nature, and responsibility. She took the time to put her thoughts on paper, to stabilize them even while they likely remained tossed about by the waves of existential storms. By doing so, she records the reality of those storms themselves. There could be no better title for Elizabeth’s story than The Hurricane Notebook because her narrative serves as something of a calm place from which to then see the waves and wind that have passed and that which is yet to come. This book is less about her own life than it is an opportunity for Elizabeth, perhaps unintentionally, to invite us to sit awhile, to pay attention to where she was and why it matters, so that we can then better figure out how to put down the book and get back to the hard swimming required in our own existential storms.

Kierkegaard often comments that faith is like being suspended above 70,000 fathoms. I have often wondered what it is to which Kierkegaard imagines us clinging at that moment. Is God meant to be something like a life-preserver that just happens to be thrown down to us? If so, then why didn’t whoever threw the life-preserver just throw us a rope and get us out of the water? Is God meant to be something like a log that happens to float by and to which we can gain some much-needed buoyancy? If so, then it seems like everything is more a matter of luck, than love.

Eventually, I came to realize that Kierkegaard’s point is not that we should cling to something on the surface, but instead that faith is the fact that we can avoid drowning only by swimming straight down—by diving into the depths, in trust, in hope, and yet not without risk. The Hurricane Notebook is Elizabeth M.’s attempt to dive into the depths of her own life with all the trauma, the uncertainty, the confusion, and yet also the small joys, the beauty of fleeting conversations, and the lasting truth to which those conversations might lead. Thankfully she does the hard work required to invite others to travel with her into these depths. She writes because she is not alone. We read because she invites us to be with her. She invites us out to where we find ourselves suspended above 70,000 fathoms and yet then calls to us from the depths, telling us that the water is fine.

Perhaps in reading her story we can begin to understand why ocean lifeguards dive under waves—because the water is calmer beneath the surface. The depths are scary because they are dark, but they are also where the effects of the storm can be minimized. As she writes at the end of her text, “One way or another—when the storm comes, I will be swimming. I would rather do the diving myself” (373). We don’t avoid the storm by clinging to the floatation device on the surface, but instead by diving deep and risking drowning by learning how to breathe underwater.

In many ways, we might say that Elizabeth’s life is defined by full investment—no half measures. She is either diving beneath the waves or surfing above them, never simply treading water. As she recounts her sister, Sarah, telling her: “But when I’m surfing, God, M, when I’m riding one of those big waves, I feel like I can handle anything else life has for me. You know?” (323). Her sister goes on to wax poetic and yet profoundly existential: “Beauty is a dance of finitude upon the edge of infinity, and the waves are so, so big. I love you. You are utterly beautiful” (323). Notice the emphasis on vulnerability (our finitude as contrasted with the sublimity of infinity) and yet the resolution in concrete relationship: I love you. In this section we find Elizabeth telling two stories at the same time (the page is split into the left column being this memory of her sister and the right column being a memory of a walk with her friend, Joshua). Her memory of her sister ends with the phrase “Up above, the stars shone down upon us, and when we looked back up, they seemed to smile at us with their infinite happiness” (323). The memory of Joshua ends alternatively, and simultaneously, with her words to him: “This is the best moment, Don’t ever forget” (323). In an almost performative rejection of the “benign indifference of the universe” to which Meursault testifies in Camus’s The Stranger, Elizabeth stresses the importance of relational memory. Our identity is a matter of what we have not forgotten about the world and our experience of it. Elizabeth writes so that she won’t forget, but by writing she encourages us not to forget her, and in so doing to become ourselves.

It is interesting that so much of her book is devoted to recounting very technical philosophical conversations about the problem of evil. I admit that initially I struggled to figure out why she would spend so much time doing so—having taught over three thousand college students myself I can’t imagine very many of them devoting so much time to such an activity. Yet, at the end of the book, it all made sense. Her final few lines are as follows:

[EXT]When the pattern goes down, it comes back up dark, bloody, twisted, and we write our life in that blood.

Mom and Dad. I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean for you to lose both daughters. That’s another crime for which I’m not big enough.

Joshua, if you ever read this, I forgive you for not knowing how to answer my questions. Please have a wonderful life. What could you ever have said? I don’t know what I wanted or what I want now. I’m sorry I couldn’t have been better. Play something sad. You’ll know what. Just this one, though: Don’t laugh.

Oh, Sarah. The storm is coming. I want to live. (373–74)[/EXT]

Pay attention to what she is saying here.

She doesn’t end with any grand realizations about the meaning of life or the realities of death. Instead, she ends by admitting that the mystery remains, and yet the beauty does too: of finitude on the edge of infinity. She commits to swim, to dive, and to dance as the storm rolls in. Channeling almost a Whitmanesque demeanor she grasps the answer: “that life exists, and identity” (Whitman, “Song of Joys”). By writing, she has “contributed a verse.” By reading, we get to hear it. Rather than concluding the book with some QED at the end of the argument, she ends with continued desire. Desire is always risky. Hope is always difficult. But, only in the context of her long recounting of the conversations about the problem of evil are her words now not simple resignation. They shift past the first movement of faith into the second: an embrace of finitude as meaningful. She is not now speaking about playing a sad song because nothing matters in light of eternity, but because everything does. As the band, The Gaslight Anthem, writes in their song, “The ‘59 Sound”:

[EXT]Well I wonder which song they’re going to play when we go.

I hope it’s something quiet and minor and peaceful and slow.

When we float out into the ether, into the Everlasting Arms,

I hope we don’t hear Marley’s chains we forged in life. (The Gaslight Anthem, “The ’59 Sound”)[/EXT]

With what she realizes might be her last words, Elizabeth reaches out to those that she loves. She tries to make amends, to ask forgiveness, to give it, and to dive deep into the risky hope that defines the fragility of the human condition.

Kierkegaard says that the knight of faith is able to find the sublime in the pedestrian. In so doing, he, like Elizabeth, realizes that the song being played at your funeral is not somehow disconnected to the deep conversations about theodicy. Instead, wherever one comes down on the problem of evil, we should choose that song well in order to let the song of our lives continue to invite others to dance (even if sad, please don’t laugh—don’t miss the importance of paying attention to where you are and why it matters).

With these last words, she encourages her reader to use their words well. As she prepares to swim out into the storm, she reminds us that we are always, already swimming.

In the end, even if Socrates was right about the potential problems of writing, I am glad that his view has not carried the day. We write not in spite of our being mortal and dynamic, but precisely because of it. We write and read in order to know that we are not alone. When we realize that we are not alone, we should go invite others to become part of our story. Elizabeth’s book is not simply an opportunity to learn about her life; it is a call to become invested in our own. Like Kierkegaard’s use of pseudonyms, Elizabeth speaks to us because it doesn’t really matter if her story is historically true (maybe this story is an invention of the mind of the editor, Alexander Jech?), it is existentially true. It is true in the way that matters most. It does not give us answers to questions that we ask, but instead puts us into question so that the lives that we live (and write) might become the answer we are willing for others to read.

Works Cited

The Gaslight Anthem. The ’59 Sound. SideOneDummyRecords, 2008.

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

M., Elizabeth. The Hurricane Notebook: Three Dialogues on the Human Condition. Edited by Alexander Jech. Wilmington, NC: Wisdom/Works, 2019.

10.18.21 |

Response

In Praise of Open Endings

In her introduction to The Hurricane Notebook, Megan Fritts enumerates the genres to which the book might be thought to belong: philosophical dialogue, Southern Gothic, Greek tragedy, and, notably, “philosophical Gothic” (THN, xi), finally suggesting that the reader is being presented with a specimen of an entirely new genre. At the same time, there are reasons to think that the book intends to exemplify one of the oldest literary genres in existence—namely, wisdom literature, understood broadly enough to include fictional narratives such as The Pilgrim’s Progress. While the diary of the mysterious Elizabeth M. is, in terms of the genre, simply a diary, publication transforms it from a personal document to a novel, making it a vehicle of an existential message which the reader is urged to embrace. Though various authors are alluded to in the text, it is clear that Elizabeth’s favourite thinker is Kierkegaard, whose philosophy runs through the book. Because of that, I will focus on the Kierkegaardian themes.

Wisdom literature is a genre naturally fraught with difficulties, since, in the words of Keats, “we hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us—and if we do not agree, seems to put its hand in its breeches pocket” (86–87). One way to avoid the reader’s distrust is to provide him with some evidence in the form of authentic experience, so the origin of The Hurricane Notebook makes its task easier. The decision to make it accessible to a broader audience is easy to see as an exercise in indirect communication, recommended by Kierkegaard as a way of pushing someone from aesthetic into religious perspective. According to the author of Fear and Trembling, the first and default stage of life is the aesthetic one, characterized by the focus on fulfilling one’s desires and collecting experiences, so that one is guided by what is interesting and fulfilling rather than what is morally good or commanded by God. In order to move to the ethical and ultimately religious stage, one needs to acknowledge one’s moral responsibility and thus guilt, from which only God can liberate. That, in essence, is what happens to Elizabeth, which makes her story a perfect tool of changing the mind of the reader who, like Elizabeth long before the beginning of the book, is stuck at the aesthetic stage—so as “to win and capture him completely by means of an aesthetic portrayal and . . . to introduce the religious so swiftly that with this momentum of attachment he runs straight into the most decisive categories of the religious” (Kierkegaard, 51). That this is the intention of the author (or the editor) is confirmed by the book’s dedication to “the learner,” a Kierkegaardian figure of an addressee of this existential message, but also by the formal and thematic structure of the book, reflecting that of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or.

As noted by Peter Lamarque and Stein Haugom Olsen (332–33), the statements literature might make concerning human condition tend not to be a subject of debate—a feature which differentiates literature from philosophy, which makes claims in order to invite an argument. This suggests that attempts to argue with the message of a literary narrative are by definition uninvited (perhaps especially so in the case of a personal diary). However, things are different when it comes to philosophical dialogue, a kind of conversation favoured by Elizabeth M. and her friends and filling a large part of the book—especially that I share the suspicion of the editors that its characters are fictional. (Though I would venture the hypothesis that Simon, with his complex personality and internal contradictions, is someone Elizabeth really met). At the same time, sharing Kierkegaard’s conviction that a literary work cannot be discussed without taking into consideration its aesthetic characteristics, I will discuss said message in relation to its literary context, drawing my premises from comparing The Hurricane Notebook with another book. What I will say is going to touch upon the issues of sin and the Fall—both of them crucial to the book’s take on Christianity—but I will avoid entangling myself in doctrinal details, focusing on the two literary universes and leaving to the reader the assessment of possible theological consequences of my position.

Fritts suggests that The Hurricane Notebook displays similarities to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, another “story of sin and undoing” (THN, xviii)—and, it can be added, another account of leaving behind the aesthetic stage of life while learning classic Greek. I will propose another point of comparison: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun. Hawthorne’s work, just like the story of Elizabeth, revolves around the themes of evil, repentance, art, memory and the past, presenting moral failure as a path to self-knowledge and personal transformation; among the main characters, each one of whom represents a different attitude to life and God, is a brooding young woman tormented by an indefinite sense of guilt. The turning points of both stories take place in the minds of the characters, not in the half-fantastic physical worlds which surround them—to the degree that some elements of the plot are left unclear. While Hawthorne explains that he wanted to write a romance rather than a novel, “philosophical Gothic” seems to be an equally fitting label for the genre of The Marble Faun: Miriam and her friends are “spokesmen for various elements of Hawthorne’s self-divisive view of his total world” (Brodtkorb, 258), just like the friends of Elizabeth M. look “as if perhaps Elizabeth herself had dreamed them all up merely for the sake of expressing in an external form her purely private spiritual crisis” (THN, viii). This makes both works reflect Kierkegaard’s idea of drama as a form of art in which the spectator finds “a vehicle for the mirroring in an external form of the myriad possibilities latent in his own (emergent) self-consciousness,” so that “the real action . . . takes place in the medium of the imagination” (Pattison, 113).

In spite of all these analogies, the resolution and message of the Hawthorne’s book is the opposite of those in the story of Elizabeth. By developing a paradox mentioned by Kierkegaard, I will show why The Hurricane Notebook would be better off without definitely condemning the perspectives of some of its characters—perspectives whose crucial elements are depicted more favourably in The Marble Faun. (The latter, known as Hawthorne’s most complex work, has been read in very different ways, and, since justifying my interpretation would divert me from the main topic, I will openly admit I am choosing the reading which best suits the purpose of illustrating my case.)

When we encounter Elizabeth M., she has already crossed the line dividing the aesthetic and ethical stages of life after the tragedy which befell her sister. Before that, she was Kierkegaard’s “reflective aesthete,” striving to fulfil her personal ethical and intellectual ideal, but also struggling with boredom and hidden despair. To cope with her sense of guilt, she examines different existential options related to religion, gradually ruling out the attitudes towards herself and God which do not take into account the necessity of submitting to judgment and complete transformation. The people whom she meets during her journey help her reach her conclusion by gradually showing their true colours and, presumably, the true colours of their ideas: the man who chooses to stay at the aesthetic stage is revealed to be selfish and irresponsible, an existentialist rebel admiring Melville’s Ahab turns out to be a Satanic figure, and a stern teacher-cum-lawyer ends up a self-sacrificial saviour. When the symbolic hurricane ends, nothing of the aesthetic perspective is left in Elizabeth, and her approach to evil and human nature has shifted from mildly Pelagian to decidedly Augustinian; she is open to receiving God’s saving grace and becoming a Kierkegaardian true Christian. During her journey, she reflects on such themes as friendship, abandonment, self-knowledge, the nature of artistic performance, and the relation between the student and teacher. I will focus on Elizabeth’s, and the novel’s, conclusion concerning the nature of evil in the context of the aesthetic perspective. Kierkegaard’s idea of the aesthetic and of its relation to the ethical and religious is complex and my reasoning is bound to involve some simplifications, but the gist of it is independent of the points of interpretative controversy.

In The Marble Faun, darkness creeps into the seemingly idyllic life of the four main characters when one of them, Donatello, kills a mysterious man following and visibly frightening his beloved Miriam, a young painter with unknown past who has recently moved to Rome. The rest of the story focuses on the complex changes in the personalities and relationships of the four friends resulting from their encounter with evil (the alternative title of The Marble Faun was Transformation). The characters in Hawthorne experience this encounter as much more inevitable than Elizabeth M.: they find themselves immersed in darkness in spite of their best intentions, and thus experience tragedy rather than guilt. This is especially true about Miriam—a refugee from fate—but also about Donatello, who kills in defence of the woman he loves, and Hilda, who rejects Miriam’s friendship in order to preserve her own innocence. Hilda’s fear of Miriam highlights the fact that in The Marble Faun evil functions like a contagious disease, easily passed on to those who care for the already affected. Miriam, just like Elizabeth M., feels burdened with the death of someone she did not kill—but, unlike Elizabeth, who fully embraces guilt and responsibility for what happened, remains “blackened by evil beyond words and yet somehow still innocent” (Dunne, 34).

As a result of their perception, Hawthorne’s characters, though in various ways changed by the realization of the reality of evil, to some degree retain the aesthetic perspective. While Donatello’s transformation, ending with his free choice to go to prison, can be described in terms of moving from the aesthetic to ethical stage of life, he seems to experience the whole process as a tragic necessity—and Miriam, embracing the sorrow resulting from her personal tragedy, is a classic instance of Kierkegaard’s melancholic aesthete. Where Elizabeth M., determined to reach the truth about herself, is convinced that “hope is the principal means by which someone is caught by a lie” (THN, 47), Hawthorne’s characters are interested in hope much more than in truth, seeing themselves and each other through the lenses of the narratives inspired by the surrounding works of art—like the portrait of Beatrice Cenci, with whom Miriam seems to identify. The vision of God shared by all four is ambiguous, varying between fearful rebellion and the hope that he will somehow free them from judgment and restore their lost happiness—two attitudes firmly rejected by Elizabeth but in their position entirely understandable.

In short, the perception of Elizabeth M. and the characters of The Marble Faun—especially Miriam—reflect two sides of the coin which is the experience of evil: as, respectively, intrinsic and external to humans, connected to agency and guilt on the one hand and necessity and tragedy on the other. Such diagnosis would, of course, be vehemently rejected by Elizabeth, who would argue that the perspective opposite to hers results from the absence of self-knowledge, natural at the point where no effort has been taken to purify the judgment clouded by the original sin. But the original sin and its consequences are constantly at the centre of attention of Miriam and her friends, who “are forced to self-knowledge in order to fulfil themselves as participants in the drama of a fallen humanity” (Hall, 93). The process of self-cognition undergone by Miriam and Elizabeth is similar, but they cannot help finding different things at the end of it. If Miriam’s conviction that her position is tragic is less real than Elizabeth’s certainty of guilt, it is only because Miriam is fictional—but, if we remember that both stories take place in a universe created as the stage for an existential drama, Miriam’s experience may not be necessarily less authentic. This symmetry may serve as evidence that the aesthetic perspective on God and evil deserves equal treatment—or at least equal hearing.

Additional reasons to take the aesthetic perspective into account turn up when the existential message is conveyed by literary means. According to Kierkegaard, indirect communication of ethical and religious truths by means of literature is so difficult because literature belongs to the sphere of the aesthetic, naturally inimical to the ethical and religious perspective; this creates a complex paradox, present in every work of art which tries to convey an ethical or religious message. In the summary of Gabriel Josipovici (112–13):

Kierkegaard wished to draw our attention to the fact that aesthetic objects have a property which makes them absolutely different from the real world, and that we should beware of ever blurring the distinctions between the two. . . . In life we have to make choices (which implies renunciation) whereas in art we do not. The sphere of the ethical, says Kierkegaard, is that of either/or; that of the aesthetic is and/and. . . . Now if Kierkegaard is right, he is faced with a real problem. For how can he argue his case against books, when he has only books to argue his case with?

According to Josipovici, Kierkegaard’s diagnosis can be applied to contemporary literature in general, which (unlike pre-modernist fiction) is full of undetermined states of affairs, making up universes which cannot correspond to physical reality. Let us note that without this property of literature philosophical Gothic would not be possible: a literary universe reflecting a personal drama of an individual can only operate within the aesthetic framework of open possibilities and suspended judgments, diverging from literary realism. This, in turn, suggests that the refusal to take the aesthetic perspective into account, while making use of the modern literary toolkit—which The Hurricane Notebook utilizes with gusto—carries with itself the risk of sounding false or at least artificial. (A further-reaching conclusion would be that the openness and suspension characteristic for the aesthetic stage of life are natural, inevitable elements of human condition as subjectively perceived—provided that literary depiction of the latter, exemplified by the diary of Elizabeth M., can be faithful at least to some degree.)

It is the idea of suspension that forms the core of The Marble Faun’s answer to the classic objection against the aesthetic perspective, namely, that it is amoral—which in The Hurricane Notebook is signalled by Joshua’s decision to break up his relationship with Elizabeth for a “beautiful life” of a professional dancer. While it is debatable whether Hawthorne’s book, as some critics insist, centres around the idea of felix culpa, the experience of moral failure, in spite of all the suffering it brings, does have some positive impact on the characters, imbuing them with maturity and wisdom; the core of this wisdom is the reluctance to judge and condemn. In Hawthorne’s book, paradoxically, the decision to abandon a friend is made as a result of the preoccupation with morality rather than not minding it. “The pure, white atmosphere, in which I try to discern what things are good and true, would be discolored” (TMF, 162–63), says Hilda to Miriam as an explanation why she cannot be her friend any longer—a decision which contributes to Miriam’s despair. In Hawthorne’s literary universe, being good to others results from embracing the vision of evil as tragedy rather than guilt; when it comes to the latter, the book suggests, it is best to suspend judgment—a message highlighted by the fact that the reader never learns whether Miriam was guilty of any crime. Hawthorne’s decision to make her guilt ambiguous is consistent with the book’s openness, embodying the aesthetic perspective. As an example of this kind of openness, Josipovici mentions Kafka’s reluctance to tell the reader whether Josef K. is guilty; notably, Josef’s “How can a person be guilty anyway?” (Kafka, 152) sounds like the opposite of “Everyone is guilty” (THN, 83), in The Hurricane Notebook the motto of Simon. As a sidenote, we may mention that it is not obvious that the sentiment of Miriam (and Josef K.) constitutes a departure from Christianity: as noted by David Parker (5–6), the tendency to abstain from moral judgment is exactly what may be expected from the literature written in the society significantly influenced by the Christian view of the world.

Importantly, The Marble Faun does not call for the rejection of the ethical but for the preservation of the aesthetic within it or along with it. Once Donatello killed the man from the catacombs, neither he nor his friends can remain consistent aesthetes—but they, along with the reader, are invited to keep seeing the world to some degree from the aesthetic viewpoint. As a result, the universe of The Marble Faun is ambiguous: in Kierkegaard’s terms, suspended between the aesthetic and the ethical. The critics suggest that it is exactly this suspension and ambiguity that, in spite of the gloomy ending, provides the book with the element of optimism, since the events take place in “a world where ‘might’ allows the reader to assume both ‘is’ and/or ‘is not’” (Auerbach, 105). This gives rise to a hope stemming from the uncertainty surrounding guilt—the hope to which Miriam clings with the intensity equal to that with which Elizabeth rejects it. Whichever one of them is right, I hope to have shown that Miriam is not without her reasons.

From the perspective of Hawthorne’s characters, it makes sense to hope that God will make things right in the end without the necessity of any further sacrifice on the part of already broken human beings—the view of Max from The Hurricane Notebook. It also makes sense to fear that God who judges and transforms may be humanity’s mortal enemy, which in The Hurricane Notebook is the attitude of Will and Sal, Will’s more menacing philosophical cousin, who insists that “one must imagine Ahab happy” (THN, 6–7). While the views of Hawthorne’s characters do not exactly correspond to those of Sal, Max, and Will, there are enough common points for the analogy to be illustrative. If such views stem from authentic experience, then—a very Kierkegaardian implication—they may lead to alternative roads to God. But, independently of that, if the experience of Hawthorne’s characters reflects a part of reality, behind the views of the characters such as Max and Will is something more than, respectively, naivety and pride—and perhaps the story of Elizabeth would be more convincing if they were not dismissed so easily. This is so especially that the message of the novel—if Josipovici’s remarks about modernist fiction can be extrapolated so sweepingly—goes against the general tendency dominant in contemporary literature. The Hurricane Notebook can be compared to some works of J. R. R. Tolkien in that it invents a new genre in order to, in some respects, resurrect an old standpoint—an impressively ambitious goal and precisely because of that in need of considered justification, so as to show that the spirit of the times is taken seriously as an opponent. One way to achieve this would be to make the ending, already wide open in terms of a plot, more open in the philosophical dimension, by signalling that the stories of Elizabeth’s philosophical opponents—especially Sal, more credible as an advocatus diaboli than as the figure of devil—might somehow end well and that this does not require that they entirely exchange their views for that of hers.

What I said does not amount to an argument with clear premises and conclusion, but I hope it gives some support to the view that some of the corollaries of the views dismissed by Elizabeth M. are worth more attention than she gave them—even in the light of Kierkegaard’s philosophy and especially in the literary context. Of course, every book has the right to have whatever message it wants, and I am not saying that I wish The Hurricane Notebook agreed with The Marble Faun, or that it should forever suspend its judgment on the matters on which they differ. I just think that, given how clear is the book’s desire to influence the views of the reader, balancing this desire with a less harshly definite message would make it easier to fulfil. One does not have to imagine Ahab happy—but perhaps it would be good to try, at least part of the time? After all, as Paul Brodtkorb (266) says about The Marble Faun, “it is of course possible to argue that the ending is not as either/or as it seems.”

Works Cited

Adamson, Jane, et al., eds. Renegotiating Ethics in Literature, Philosophy, and Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Auerbach, Jonathan. “Executing the Model: Painting, Sculpture, and Romance-Writing in Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun.” ELH 47.1 (Spring 1980) 103–20.

Brodtkorb, Paul, Jr. “Art Allegory in The Marble Faun.” PMLA 77.3 (June 1962) 254–67.

Dunne, Michael. “‘Tearing the Web Apart’: Resisting Monological Interpretation in Hawthorne’s Marble Faun.” South Atlantic Review 69.3/4 (Fall 2004) 23–50.

Hall, Spencer. “Beatrice Cenci: Symbol and Vision in The Marble Faun.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 25.1 (June 1970) 85–95.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Marble Faun (TMF). Edited by Susan Manning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Josipovici, Gabriel. The Lessons of Modernism and Other Essays. London: Macmillan, 1977.

Kafka, Franz. The Trial. Translated by Mike Mitchell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009

Keats, John. Selected Letters of John Keats. Edited by Grant F. Scott. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Kierkegaard, Søren. The Point of View. Edited by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Lamarque, Peter, and Stein Haugom Olsen. Truth, Fiction, and Literature: A Philosophical Perspective. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

M., Elizabeth. The Hurricane Notebook: Three Dialogues on the Human Condition (THN). Edited by Alexander Jech. Wilmington, NC: Wisdom/Works, 2019.

Pattison, George. Kierkegaard: The Aesthetic and the Religious; From the Magic Theatre to the Crucifixion of the Image. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

Sr. Ann Astell

Response

Mirrors of Freedom, Fatherhood, and Faith in Alexander Jech’s The Hurricane Notebook

In one of the mysterious notebooks included within Elizabeth M.’s notebook, the pseudonymous author “Niakani” remarks, “I’ve been reading Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky like mad, and I feel I am on the verge of working out a solution.” Having co-taught a Philosophy and Theology seminar with Alexander Jech on Kierkegaard and Dostovesky, I cannot resist returning to the three themes we emphasized in that course—Freedom, Fatherhood, and Faith—in my remarks on Jech’s wonderful new philosophical novel, The Hurricane Notebook. From Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, Jech has drawn inspiration for the fictional notebook itself with its collection of entries by more than one writer, on a series of topics and in styles suited to different genres. From Dostoevsky, Jech has learned how to juxtapose characters who mirror each other in complex ways, not merely as literary foils sometimes enhance a hero’s stature, but as representatives of different philosophical perspectives and choices and as a means for each other’s growth in self-knowledge. These human mirrors, unlike the glassy mirrors in Sal’s house and the formula-laden mirrors in Elizabeth’s parental home (“The Sacrum Arcanum”), allow Elizabeth M. to see herself, to remember herself, in ways that are ultimately life-giving and life-changing.

When we first encounter Elizabeth, she has isolated herself in her apartment, feels “profoundly alone” (5), lacks any relish in living, walks the empty streets at night, is haunted by the memory of her sister Sarah, a recent suicide. She exemplifies “the sinner curved in upon himself” (102). This isolated existence of Elizabeth’s—monochromatic, monotonous, depressive, guilt-ridden, disgusted—is, in turn, a tragic consequence of her earlier withdrawal from the two relationships of human friendship that had been important, beautiful, and joyous for her: those with Joshua and Sarah.

As Elizabeth explores her memories in the seemingly disjointed fragments of the notebook, we encounter Joshua as Elizabeth’s partner in ballet, the dance whose beauty becomes a means and expression both of their relationship and of Elizabeth’s personal wholeness within it. Through Elizabeth’s love for an idealized Joshua—a love that Niakani (echoing Kierkegaard) would call a “self-making passion”—the teenaged girl has made ballet the “pattern” of her life, devoting herself completely to its practice, despite her realization that her talent as a dancer is inferior to Joshua’s. Bitterly disappointed when Joshua leaves to pursue his study of ballet in New York City, Elizabeth’s life loses its wholeness, the “synthesis” she has “posited” (again to echo Kierkegaard’s and Niakani’s language). She embraces the mathematical beauty of chess-playing as a substitute for the pattern of dance, but even her chess-playing, which had formerly been a means for an open relationship with others, becomes different, aimed instead at winning and control. “In chess,” she admits, “making the other player hear the music is a kind of seduction, to trap him” (196).

Her chess-playing (traditionally a symbol for the combination of necessity and freedom in the human condition) becomes an outward sign, a patterned expression, of her willful adherence to “The Sacrum Arcanum,” the abstract ideal that becomes her new “self-making passion.” Elizabeth transforms the old playroom at home, which had been converted “into a home dance studio,” into “The Sacrum Arcanum,” covering the mirrors on its walls with formulaic assertions written with “a black dry-erase marker” in what became “a kind of private language” (153–55). The handwriting on the glass symbolizes her commitment to two assumptions: “One was that the idea, the ideal, was articulable. The second was that the individual was sufficient for the relation to the ideal” (156). Elizabeth’s commitment to an ideal self-sufficiency—embraced as a protection against disappointment and betrayal in relationships—thus becomes her “destiny,” “her whole relation to the world” (156), with tragic consequences for her younger sister Sarah, who in turn feels abandoned and betrayed, and for Elizabeth herself.

When a bewildered Sarah appears on the scene and asks, “What is it?” Elizabeth replies that she cannot explain it to her, asserting that “The Sacrum Arcanum” is vastly different from the “Arcanum” that the two girls had earlier invented as the secret “Twig Latin” of their childhood friendship and imaginative adventures. “The Sacrum Arcanum” belongs to Elizabeth alone. As children, Elizabeth and Sarah had pledged (making exuberant use of a cross-lingual pun) to “re-dime” / redeem one another; they had opened their souls together to the beauty of the world through surfing, dance, and poetry. Abandoned by Joshua, whose dancing complemented and contributed to their shared sense of beauty, a willfully self-sufficient Elizabeth in turn abandons Sarah, who then, rebelliously and sadly, abandons herself to a decadent life of beach-parties and drink. The two sisters no longer speak the same language, share the same interests, move in the same circles. The hyper-virtuous Elizabeth actively avoids and disdains Sarah’s company. Lacking Elizabeth’s Hyperion autonomy, Sarah clings to the party crowd, but also to the memories of childhood beauty and bliss that her sister has forgotten—a fact Elizabeth subsequently discovers through the heart-rending evidence of a left-behind LP record, a letter, and a poem (237). Sarah’s memories, in turn, allow Elizabeth to remember herself—her guilt, but also the ground of her hope for a renewed life.

The chapter entitled “The Black Swan” brilliantly interprets the human/swan transformations in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake as symbols of the perilous transformation of childhood potential (itself a mixture of necessity and freedom) into adult realization. The ballet and the LP recording of Tchaikovsky’s music were important to Elizabeth in her adolescence, inseparably connected to her relationship with Joshua and her memories of him, but also (Elizabeth discovers) to Sarah in her memories of her ideal, her older sister. Elizabeth finds the old LP of Swan Lake, to which she had once danced in Sarah’s company, in her dead sister’s bed—a discovery prompting her compunctious meditation. In the double identity of Odette/Odile, Elizabeth understands herself as one betrayed and betraying. The “joint suicide” (196) of Siegfried and Odette/Odile seems to Elizabeth to have announced “a universal fate” (199), but also the particular, tragic necessities of Joshua’s betrayal of her through withdrawal and of her own betrayal of self and sister. “Swan Lake,” writes Elizabeth, “is my definition, my doctrine of sin, this account of freedom and its loss. . . . Being loved is to kill” (213).