The Enchantments of Mammon

12.1.20 |

Symposium Introduction

Good things come to those who wait. For some of the respondents in this symposium they have been waiting for Eugene McCarraher’s The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity since 2005 when McCarraher first published an article by the same title. For the rest of us, the COVID-19 pandemic has thrust us into an uneasy season of waiting—waiting for a vaccine, waiting for the ease of travel, waiting to embrace faraway loved ones, waiting to worship next to our fellow congregants again. A few weeks ago, as my partner walked through her empty church congregation, she saw a Lenten banner proclaiming, “How long, O God, how long?” She later said, “I feel like this has been one long season of Lent.” As I write this introduction, Advent is coming, but I am already too familiar with the depths of anticipating a new world. Many of us actively anticipate a new world free of the entrapments of neoliberal austerity politics and would-be strongmen who use the government’s military to violently suppress protesters proclaiming the value of Black life. As we anticipate liberation, McCarraher’s book can help us realize how deeply fallen our world is—how deeply misenchanted it is by the religion of capitalism and its pecuniary logic.

McCarraher offers a forgotten tradition of imaginary power to encourage our waiting. “The earth,” McCarraher writes, “is a sacramental place, mediating the power and presence of God, revelatory of the superabundant love of divinity” (11). Contrary to popular academic discourse today, our modern world is not disenchanted and religion has not retreated from the scene. Instead, we are living amidst one of the most successful religious transformations our world has ever seen: Capitalism did not disenchant the world, but misenchanted it. McCarraher’s intellectual history of this phenomenon is awe-inspiring in breadth: covering topics and eras like the Diggers, Puritanism, American democratic thinkers like Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Socialist, leftist, and labor movements, Fordism and corporate management literature. In page after page, McCarraher traces out exactly how Capitalism is the dominant religion today and where we might draw resources to imagine resistance.

Imagination is a crucial form of vision for McCarraher, for the tradition that he believes offers the strongest and best counter to the religion of capitalism is the Romantic tradition, or more precisely, as Nicholas Hayes-Mota rightly points out, left Romanticism. Left Romanticism fostered a sacramental imagination that is a “mode of realism, an insight into the nature of reality that was irreducible to, but not contradictory of, the knowledge provided by scientific investigation” (16). Only a sacramental imagination and its “theology of wonder” can offer an ontology and theology strong enough to defeat capitalism’s misenchantment (21).

The participants in this symposium consider the political, economic, theological, and cultural significance of McCarraher’s monumental and important work. McCarraher is a historian and so the book itself is admittedly slim on “good” theology as William Cavanaugh writes (it is certainly full of “bad” theology). Hayes-Mota freely admits that his own experience in the Occupy and New Economy Movements perhaps makes him one of the readers McCarraher had in mind when writing this book, but is not convinced that left Romanticism is a politically viable avenue to the kind of socialism McCarraher envisions. Tracy Fessenden calculates that Enchantments would take the better part of a work week to read through. It is a work of the academy, and largely for the academy, and so is a complicated work bearing the characteristics of its current formation. Yet, as McCarraher reminds us, the sacramental imagination of the left Romantic tradition may have something to offer its readers—perhaps books do still change reader’s lives and the brutality of capitalism has not deprived us of that fact. Fessenden’s response to Enchantments is especially powerful, in my mind, as her insights point out how even in as complete a work like this, new models of inspiration and imagination can be left out, as Fessenden lifts forgotten feminist figures in McCarraher’s own tradition. Philip Goodchild, who finds himself broadly in agreement with McCarraher, critically examines the frame of enchantment for analyzing capitalism. Ken Surin considers how McCarraher’s thesis might apply to forms of capitalism outside the Western world.

I began this introduction with a brief reflection on the season of waiting in which we find ourselves and I claimed that Enchantments can unveil the deep religious roots of capitalism’s misenchantment in our world. I will end this introduction on my own critical engagement with the work. McCarraher’s account—as thorough as it is—is largely silent on the tradition of Black radicalism and racial capitalism, that has long recognized, as Ida B. Wells wrote, “The White man’s dollar is his God.” McCarraher rightly recognizes how US American capitalism would not be what it is without the brutality of chattel slavery and that the religion of slaves carried its own incisive critique of white slaveholding capitalism: “As most renowned slave rebellions demonstrated, the enchanted world of antebellum African-Americans could reveal moral and metaphysical evil with incisive and terrifying vividness” (172). And later in reflecting on the theological significance of slave rebellions and the writings of Nat Turner, “The sacramental theology of the slaves—inhabitants of an enchanted world bereft of any secular, immanent frame—bore the keenest critique of the enchantment of Mammon before the Civil war” (175). But these lines aside, my question can be put forcefully as follows: Can one purport to give a complete history of the religion of Capitalism in our modern world without examining how that religion itself is racialized and deployed to the benefit of economic and political structures that presume to define what is normal—capitalist heteropatriarchal white supremacy?

A deeper engagement with the Black radical tradition would require, as Goodchild points out in his response, that we get a bit more precise of a handle on what we mean by “religion” itself and how it operates. McCarraher’s left Romanticism, as Hayes-Mota suggests, may be ill-equipped to effect the political change he seeks to lift up. The Occupy Movement and the Bernie Sanders campaign are provided as examples, but we should also remember that the Movement for Black Lives policy platform has one of the most radical economic platforms articulated in recent years.

McCarraher has given us a gift of high importance and the simplicity of his thesis does not diminish his brilliance: the world was never disenchanted but rather misenchanted by the religion of capitalism. The book needs to be read by all who study and consider the political, cultural, theological, and economic significance of capitalism in the modern Western world. He has inspired our imagination with visions of a world free of capitalism’s allure and filled with a Romantic sacramentalism. The hard work of building such a world lies to all of us, and we are better equipped for it by McCarraher’s labor.

Response

Introduction to Replies and Reply to Fessenden

Introduction to Replies

Thanks to all of the contributors to this symposium on The Enchantments of Mammon. They convey their praise and criticism with admirable verve and lucidity; indeed, if I’d had them as readers while writing over the last twenty years, the book would have been immeasurably better. And since they’re all broadly sympathetic to the argument, I salute them for their (mostly) impeccable taste and judgment. In reply, I want to say a bit about the origins of the book, focus on what I consider the sharpest and most provocative criticisms, and discuss some of the theological and political implications that they perceive.

In the late 1990s, I was finishing my first book, Christian Critics, a study of liberal Protestant and Roman Catholic social thought and cultural criticism in the United States in the twentieth century, and I was thinking about how one might move from writing about religion as a historical subject to enlisting religion and theology as tools of historical scholarship. Some religious historians were complaining that religious perspectives on history weren’t taken seriously by the discipline as a whole; they wanted “a seat at the table,” as George Marsden put it. While I shared the complaint and the desire, it seemed to me that if we historians “of faith” (to use that clumsy phrase) wanted to sit at the table, then we should have something interesting and compelling to say once we got there. It also seemed to me that, rather than vainly and fruitlessly search for the hand of Providence in history (which is what many of these historians seemed to want), perhaps we should think in theological terms about what human beings are doing. What do the images and likenesses of God desire in the terrestrial realm of history?

That’s one set of questions. Another was emerging from the world that was being born from the maelstrom of 1989, and the apparently final, irreversible victory of global capitalism. This isn’t the place to narrate the rise of what we now call “neoliberalism,” but let it suffice to say that politicians, entrepreneurs, business executives, and elite journalists began to insist that everything had to be recast in the image and likeness of the marketplace, from public agencies (“reinventing government,” as the euphemism went) to one’s personal identity (“Brand You”). “Government should be run like a business,” was the refrain. Indeed, the acolytes of neoliberal ideology attributed an eschatological imperative to the Market. Figures such as Francis Fukuyama were announcing “the end of history,” the consummation of all human endeavor in liberal capitalist democracy. President Bill Clinton informed a meeting of the WTO in Geneva in May 1998 that the worldwide spread of capitalism had ushered in “the fullness of time.” In 2000, John Micklethwait and Adrian Woolridge, Washington correspondents for the Economist, wrote with no irony or embarrassment of the “broad church” of neoliberalism. Forecasting an “empire without end” directed by an elite of “cosmocrats,” they aligned the sway of the United States with the neoliberal trajectory of history, citing Sir Robert Peel’s Tory invocation of “the beneficent designs of an all-seeing Creator.” What struck me was the almost laughably religious import and idiom of this language. But at times it wasn’t so laughable: to wit, Thomas Friedman’s weaponized prophecy in a 1999 essay in the New York Times Magazine:

For globalization to work, America can’t be afraid to act like the almighty superpower that it is. The hidden hand of the market will not work without a hidden fist. McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonell-Douglas, the designer of the F-15, and the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technology is called the United States, Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps.

(Friedman would top that pronouncement. Four years later, asked by the interviewer Charlie Rose why the United States had invaded Iraq, Friedman replied with his signature grandiloquence: “Suck on this.”)

What also struck me and a handful of others was the triumph, not only of business, but of business culture, the sheer inescapable ubiquity of business vernacular and imagery in everyday life that seemed more pervasive than at any other time in history. (The many essays on business—“the God that Sucked”—in the Baffler provided a lifeline for me at this time.) In advertising, marketing, and public relations; in management-speak and financial journalism; in the stream of stock prices that seemed to frame every image on cable news networks—Business inscribed its commands and desires in the firmament of popular culture. And some of the imagery was beautifully, hauntingly enchanting. Two examples come to mind. The first I saw as I watched TV in my hotel room while at a conference of the American Historical Association: a Microsoft ad in which an older Black woman sits on a bench as children dance around her in slow motion, with her arms extended like the Hindu goddess Kali. Another was an Infiniti ad, depicting a bird flying slowly against a background of ominous clouds. We never see an actual Infiniti, but we do hear one word: “Infiniti.”

I began to be impressed by the religious aura that surrounded these images—and putting that together with the eschatological import of elite neoliberal discourse, I started to wonder: is capitalism taking on the quality of a religion? If so, how did we get to this point? Might it always have had this quality, one that’s only now becoming apparent? It occurred to me that, if capitalism has always had religious features, then one of the main stories that intellectuals tell themselves about modernity might be wrong: “the disenchantment of the world,” as the sociologist Max Weber called it, or the appearance of “a secular age,” in Charles Taylor’s formulation, the erosion of belief that the world is inhabited or leavened by deities, spirits, and other invisible, supernatural beings.

The Enchantments of Mammon is my answer to those and other questions about the nature and history of capitalism. It begins from a religious claim: that human beings long for what I call a sacramental way of being in the world, a form of life in which work, material objects, and human relationships mediate the presence and power of divinity. The world, as Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, “is charged with the grandeur of God.” Far from being a fully rationalized political economy—a point on which Marxists and Wall Street bankers would agree—capitalism addresses, in a deceptively “secular” way, the same hopes formerly entrusted to traditional religion. The most penetrating and generous pedigree of criticism and opposition to capitalist enchantment has come, not from the secular Left, but from what Nicholas Hays-Mota dubs the tradition of “Left Romanticism,” the modern heir to the sacramental imagination which has persisted from the late eighteenth century right up to the present day. I celebrate and fully enlist in that Left Romantic lineage, and as Hayes-Mota perceives, my book is “a pedagogy for Left Romantic imagination.”

Reply to Fessenden

Although my interlocuters applaud the book as a whole, Tracy Fessenden, for instance, laments what she describes as “a somewhat static history.” True enough—though I take some issue with her contention that I always ascribe the failure of Romantic politics simply to “some variety of refusal of God’s free grace.” While that refusal is always at work in sinful human beings—even anti-capitalists—I would retort that there were other, more material obstacles to victory whose historiography I dutifully cite. I would also add—not so much in self-defense as in self-description—that while many if not most historians are interested in why and how things change over time, I’m a historian who is interested primarily in why and how things persist and endure over time. Also, even though she does so only in passing, Fessenden also rehearses one of the more annoying and facile criticisms that’s been directed at the book: my alleged idealization (her word is “romanticization”) of the Middle Ages. Apparently, for some readers, to say—as I do—that the medieval era might actually have articulated more genuinely humane standards for economic life than those upheld in capitalist modernity is to be a reactionary of the moldiest kind. On this score, I can do no better than repeat the judgment of the great historian and socialist R. H. Tawney, who observed that if medieval moralists were undoubtedly “naïve in expecting sound practice as the result of lofty pieties alone,” they did not succumb to the modern “form of credulity which expects it from their absence or their opposite.”

Fessenden rightly takes me to task for not including many women among my dramatis personae. (And my compliments to how she introduces her censure: likening my book to an exquisite linen bedcover embroidered by Mary Jane Newell. Well played.) I can only say mea culpa; my only exculpatory plea is that the corporate intelligentsia who comprise most of the cast of characters—advertisers, illustrators, technologists, managers and management theorists, industrial designers, architects, business journalists, and corporate executives—has been overwhelmingly male. But this leads Fessenden into what I think is an even more intriguing criticism: that my failure to include more women underscores a larger failure to “specify the conditions of labor,” especially those of adjunct professors whose underpaid labor enables tenured mandarins like myself to undertake research projects that issue, sometimes, in intellectually impressive but politically feckless briefs against capitalism. It vexes Fessenden that Enchantments is a product of academic comfort and leisure; it reflects the indisputable fact that tenured faculty like me have ample time and resources to produce hefty, serious tomes while “adjuncts do the heavy lifting, and students sleep in their cars.” For all its erudition and eloquence, my book, she angrily observes, will not “save the laboring child from Moloch.”

I’m not sure whether these are assertions or accusations. Perhaps they’re both; to the extent they’re the latter, I plead guilty with extenuating circumstances. As a work of scholarship, Enchantments is admittedly “history from the top down,” for the most part, since the corporate intelligentsia had and still has enormous power to draw and redraw the boundaries of the moral imagination, forging the cosmology, credos, moral codes, iconography, and sacred spaces of capitalism. As a product of contemporary labor conditions in academia, Enchantments verifies my complicity in an expensive, intensely exploitative, and baroquely hierarchical system. I clearly benefit from adjunct labor, and I’m well-paid partly because of insanely high tuition. (No students at Villanova are sleeping in cars, but many will soon be indentured to jobs they loathe in order to pay off their student debt.) But I didn’t create the conditions in which I write, and unlike, I’d wager, many other tenured professors, I’ve known the tribulations of adjunct teaching. (And, hell, for what it’s worth, I’m still paying off my student debt.)

To be sure, if my assay against capitalism “sits uneasily on the shelf,” it does so with many other volumes written by tenured radicals. But—and I write this as someone who’s usually impatient with the cheap, self-indulgent moral posturing of so many of my tribe—I honestly don’t see the point of dwelling on the terrible ironies of left-wing academic production. Like labor organizers, lawyers for immigrants, and advocates for sex workers, lefty academics are trying to right the wrongs of the world with the talents we possess. Some of us (God knows not nearly enough) fight for improvements in the working conditions of adjunct instructors. And we write books that (again, not nearly enough) people will read, ponder, and perhaps move to action. The impact that professors have on students often isn’t visible until well after they leave our classrooms; the impact that scholars have on readers is often similarly inconspicuous or delayed. (And it has to be said that their books are increasingly not being published by trade houses; it’s simply a fact that university presses are becoming the last bastions of serious intellectual work that’s aimed at engaging that elusive creature called the educated lay reader.) So despite all of the ideological absurdity and malevolence that have racked the higher learning over the last generation—none of which has done anything to impede the accelerating corporatization of academic life under neoliberal auspices—the university remains one of the last venues in this country for thinking and writing directed against the injustice and indignity of capitalism. It might be a stretch to believe it, but scholarship can help to liberate children from the gnashing maw of Moloch.

12.8.20 |

Response

A Wondrous Book

The Enchantments of Mammon is a wondrous book. The author says it is the outcome of nearly two decades of reading and writing, and the result, in addition to the formulation of an entirely original thesis regarding the intersection of Christianity, modernity, and capitalism, is a work of encyclopedic erudition.

As I read the book and wondered how I should write my review, I suddenly recalled the parable of the blind monks and the elephant to be found in Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain texts (its Western analogue being Plato’s allegory of the cave). According to one version of the parable, three blind monks hear that a strange animal had been brought into town and was drawing a lot of attention. Intrigued, they went to find out what the fuss was about. Touching it, but having no notion of what an elephant was, they had no idea of what was in front of them. Each monk was allowed by the animal’s mahout to touch one part of the creature, before being asked what he was touching. One monk touched the trunk, and said, “This is a thick snake.” The second touched its ear, and said it was a big fan. The third monk touched it its leg, and said it was a tree trunk.

McCarraher’s book can be assigned (more or less roughly) to the history of ideas, but it also dwells on literature, theology, religious history, the history of economic thought, social theory, politics, cultural history and theory, and philosophy. Hence my apprehensiveness, in reviewing The Enchantments of Mammon, about being in the equivalent place of one of the blind monks touching the elephant.

Despite its massive erudition, and complex arguments brilliantly undertaken, McCarraher’s main thesis is beguilingly simple for those who trawl in this field. Using Max Weber as his foil, McCarraher sets out to show that the great German sociologist was mistaken in his claim that modern capitalism arose from a pervasive disenchantment of the world brought about by Protestantism. Instead, says McCarraher, what happened with modern capitalism was the emergence of a different kind of enchantment, a misenchantment in which the cult of Mammon supplanted the God of the traditional Christianities, not by a sudden dethronement, but by more subtle, elastic, and uneven processes in which the theological frameworks and liturgies of these Christianities were adapted, broadened, torqued even (Mormonism being a case in point here), to encompass the Mammon of capitalism. Capitalism was thus somewhat akin to the avian cuckoo species which evolved to get other “theological” birds to hatch its eggs.

The Weberian Myth (as McCarraher calls it) has been ripe for overturning simply, but not solely, because of what social scientists would call its “selective sampling” of the historical evidence. In The Enchantments of Mammon, the Myth receives a sound intellectual thrashing, and we can say with conviction that McCarraher has given this Myth its coup de grace.

That said, The Enchantments of Mammon poses two issues for this reader, one having to do with the largely implicit or inchoate conceptualization(s) of the capitalisms underlying this book, the other with what comes next, in any kind of reading of the current capitalist conjuncture (and how this will dovetail with McCarraher’s call for a new sacramental materialism)?

When I say the conceptualization(s) of the capitalisms underlying this book are largely implicit or incipient I do not mean this as a criticism—it would take a companion volume (or a series of articles) to The Enchantments of Mammon, probably just as massive as the initial text, to undertake this, and this is not a task to be wished on anyone, even someone with McCarraher’s prodigiously expansive intellectual range.

The Enchantments of Mammon has an extraordinary theoretical scope. It begins with the medieval sacramental economy as a backdrop for the emergence of Protestantism, and encompasses such movements as the Diggers and Levellers, the emergence of Romantic anticapitalism and bourgeois society (along with Marx’s critique of the latter), imperialism, the Arts and Crafts movement, the technocracy and counterculture, management theory and advertising, postmaterialism, as well as the branches and offshoots of these movements.

So on a rough and ready reckoning, The Enchantments of Mammon covers an array of capitalisms: agrarian capitalism (both post-feudal in Europe and the eighteenth and mid-nineteenth century in the US South, the latter taking the form of a slaveholder capitalism); artisanal capitalism (wind and water as the primary technology of energy-power);1 mercantile capitalism (wind and water still as the primary technology of energy-power); early industrial capitalism (steam as the primary technology of energy-power); developed industrial capitalism (the combustion engine and electricity as the primary technology of energy-power); Social-Democratic / New Deal capitalism (Keynesianism and Fordism); digital or investor/financialized capitalism (computerized technologies as the primary technology of energy-power); extractive capitalism (the extraction of minerals and other raw materials as the economy’s engine).

Each of these capitalisms had/has their own strategies of production and accumulation, institutional and organizational structures, and subtending political, social, and cultural forms. And yet they all conduce, or have conduced, to the religion of modernity and its modes of misenchantment, culminating in the cult of Mammon. This is not to criticize in any way The Enchantments of Mammon, since McCarraher’s steady and ultimately inexorable accumulation and presentation of the evidence for his thesis shows that this was indeed the case—as long as there has been capitalism, misenchantment (not disenchantment!) and the cult of Mammon have been with us.

As I said, a useful supplement to The Enchantments of Mammon would be a companion volume conceptualizing the capitalisms that underly this book, which then links these conceptualizations to the many and varied manifestations of Mammon that have pervaded modernity.

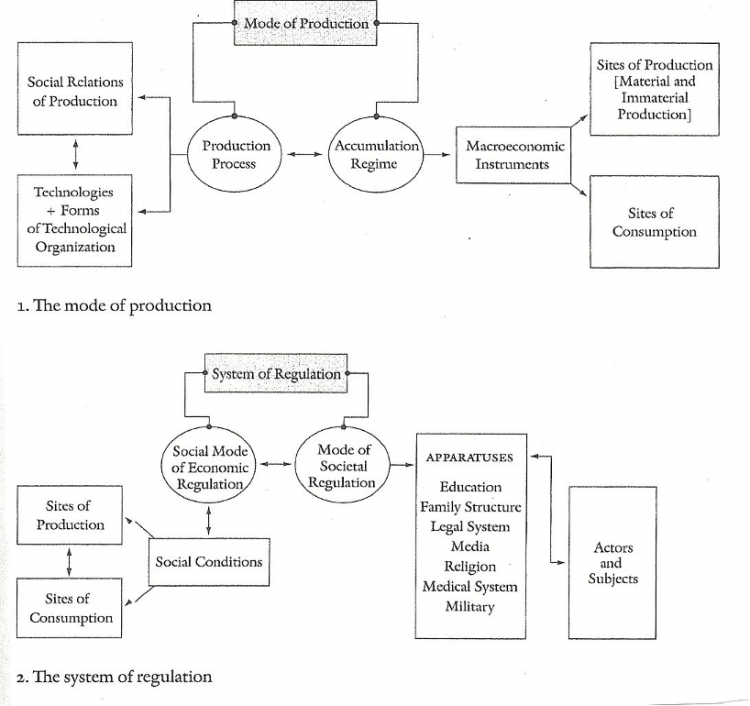

Capitalism consists of a mode of production and a system of regulation (see the diagram below).

Source: Kenneth Surin, Freedom Not Yet: Liberation and the Next World Order (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009).

The mode of production and system of regulation operate in tandem. Where The Enchantments of Mammon is concerned, the focal-point of this analysis will be on the system of regulation, and how this system generates and sustains the version of the cult of Mammon specific to it. Analyzing the differences in the system of regulation particular to this or that capitalism will be important. For instance, a prosperous Calvinist burgher in sixteenth-century Amsterdam (understood here as the personification of a form of consciousness) will embody a very different subjectivity and constitution as an actor compared to a nineteenth-century London merchant with a large tranche of shares in a Jamaican sugar plantation who also happens to be a pillar of his Anglican parish church (again understood here as the personification of a form of consciousness). Again, this nineteenth-century Anglican businessman will be quite different from a twenty-first-century millionaire Mormon investment banker in New York (yet again understood here as the personification of a form of consciousness). All three personifications in this example will be specific and different instantiations of the acquisitive urge and its associated misenchantments, even as Mammon presides over all three lives.

Another separate but related consideration, one well outside the scope of The Enchantments of Mammon because it amounts to a thought experiment (albeit one spurred by the book), will be to see if non-Western forms of capitalism shared the West’s, and Christianity’s, seemingly intrinsic predilection for Mammon-creation and worship. This task is beyond me, but here are some superficial thoughts.

We know for instance that money and markets, and thus a certain version of capitalism, existed in China long before they did in Europe, even though no industrial revolution originated in China (but did in Europe, or England specifically).2 By 300 BCE, China had a market economy, the private ownership of land, a fairly complex social division of labor, movement of labor that was relatively free, and well-developed markets for factors of production and the ensuing products.3

It is virtually impossible to provide a short description of Chinese religious traditions, these being in the main Confucianism, Taoism, and later on Buddhism, the former two preceded by animistic practices with shamanic and totemic elements. Ritual and ceremony were central to all three in varying degrees, and seen as the way for Confucianism and Taoism in particular to access the cosmic source (Tian, sometimes translated as “heaven”). The power of the cosmic source was channelled for the common people by enlightened masters and by folk-religious cults of regional and local divinities, the latter serving primarily as guardian deities.

This Chinese world was enchanted, certainly, at least in terms of the conceptualizations made available by The Enchantments of Mammon. The presence of dead ancestors was incorporated into everyday life, and the guardian deities had to be satisfied and brought onside for good fortune and prosperity.

As an anecdotal rendition of this state of affairs, I recall my visit a few years ago to the birthplace of Mao Tse-tung in Hunan province. As we approached the village where he was born, the multilane highway leading to and from it was lined at intervals with golden statuettes of Mao, with offerings at their base. I asked my hosts what this represented, and was told that the area’s prosperity was so bound up with Mao, both during and after his lifetime, that he had become a (local) deity for many people living there. Mao had after all brought them good fortune and prosperity. Communism professed to be a wholly secular belief system, which I had for some time thought improbable, and seeing figurines of Mao as a deity only confirmed that assessment.

And so this Chinese world and its attendant cosmologies, when present in the context of Chinese capitalist markets—certain generalizations permitting—never underwent anything like the pervasive disenchantments posited by those who still subscribe to the Weberian Myth. Can we say that this Chinese world has always, in this or that way, been enchanted?

There were of course from time to time in China proscriptions, persecutions even, of certain forms of religiosity, notably in the early period of Communist rule, but none of the justificatory precepts embodied in these proscriptions were elevated to a metaphysical or cosmological level, as was the case in the Christian West. The weddedness of capitalism in the Christian West to the cult of Mammon and its consequent misenchantments is therefore an entirely contingent feature of the historical development of capitalism, at any rate, it is confined seemingly to its Western manifestations. The cult of Mammon, or its cognates or equivalents, was therefore somehow not required to underpin varieties of capitalism outside the West, China in this instance.

None of this affects the substance of McCarraher’s argument, since The Enchantments of Mammon is of course confined to the West and Christianity. But it poses the question of the sheer peculiarity of the elective affinity between Western capitalism and Christianity. This cosmological or metaphysical affinity between capitalism and the West’s predominant religion has, it would seem, no ostensible equivalent in the relation between capitalism and religious traditions existing outside the West, at least where China is concerned.

Hopefully someday, someone with the requisite comparativist skills will address this crucial topic in a book or doctoral dissertation.

So what comes next, given that the current capitalist conjuncture is not, on the face of it, a propitious context for McCarraher’s call for a new sacramental materialism.

We have to face the possibility, or perhaps the reality, that capitalism in its latest embodiment has now evacuated in toto the conceptual space in which any prospectus with regard to “enchantment”—whether it be disenchantment, misenchantment, or rëenchantment, or any of their opposites or alternatives—can operate. The entirety of this conceptual space is perhaps now obsolete.

In saying this we need to bear in mind that McCarraher is certainly not an advocate of a rëenchantment of a disenchanted world. As he says in criticizing Charles Taylor, who calls for rëenchantment as a counter to secularism, rëenchantment will not be salient if it has disenchantment as its backdrop: rëenchantment will only be germane if the framework for addressing its theoretical implications and practical possibilities is provided by a misenchantment of the kind characterized by McCarraher. A misenchantment, unlike its counterpart disenchantment, is after all still an enchantment, even if it happens to be twisted into the Cult of Mammon.

So what is this so far hypothetical barren conceptual space posited by me, in which any putative disenchantment, misenchantment, or rëenchantment, can no longer operate?

We can call this particular recension of capitalism “greedy bastard capitalism,” a capitalism which has no need for any pieties or impieties or mispieties (to use a neologism), because it has reached its seemingly ultimate destination, that is, a now inextricable affinity with nihilism.

Have we therefore attained something like an ultimate in capitalist nihilism, one that has, in reaching this point of culmination, has perhaps abolished any need for the Cult of Mammon and its attendant misenchantments.

The Enchantments of Mammon represents, in all its plenitude, something of a theoretical and practical denouement for our current version of capitalism. But McCarraher’s book also portends in its superbly ramified way, this time in practice and not just theory, a far deadlier successor version of capitalism.

Ayn Rand, as depicted accurately by McCarraher, represents something of an apotheosis of egoism and self-interest elevated to the level of a cult. But Rand’s characters however are not nihilists—as McCarraher points out, she imbues these egoists with a certain nobility, implausibly crackpot notion though that may be. Randian egoists have, after all, a metaphysics, however messed up, to underpin their self-bestowed superiority as individuals.

The massive swindlers and crooks of our time—greedy bastards all—are sociopaths with no need for any cult of Mammon, let alone a botched metaphysics, to underpin their rip-offs. Bernie Madoff, Jordan Belfort (the Wolf of Wall Street), and Steve Eisman (the Big Short) are emblematic of this group, and they just grabbed what they could get.

If they had a justification for their actions, it was not a genuine self-justification, let alone one with any metaphysical basis. Rather, for them the fault lay with easy-to-fool clients, referred to by Goldman Sachs bankers as “muppets.” To quote Greg Smith, a former Goldman Sachs employee turned whistleblower, who said in an interview with CBS TV:

“Within week one [of arriving in the London office] I met a junior guy who was 24, 25 years old and the first thing he’d told me was that he had just traded a sophisticated derivative with a ‘muppet client’ who’d paid the firm an extra million dollars because the client was so trusting that he didn’t check the price with other banks,” Smith recalled. “Now you could think to yourself, is this some rogue guy who is just talking callously about clients, but his boss who’s a managing director was sitting right next to him nodding and chuckling along.”4

The image conjured here is of a pride of lions on the African savannah in search of their next meal, eying a herd of zebras or wildebeest in order to get a sense of the herd’s less speedy animals, and then moving in on these hapless creatures for an ever-so-easy kill.

Wittgenstein once said we would not understand a lion if it spoke. The Austrian sage said this in the days before computerized animation—today we can understand lions when they speak. If one such lion in my African savannah example spoke before it proceeded to maul a zebra to death, it could say to its victim: “I’m alright Zebbie, but damn hungry, so I’m going to show you how to fuck-off and die!”

Or in equivalent Wall Street banker-speak before ripping-off a “muppet” to the tune of millions: “I’m alright Jack, you muppet, so you can fuck-off and die!”

Given that we have embarked, ostensibly, on this phase nihilistic capitalism, what then of the arguments advanced in The Enchantments of Mammon, and McCarraher’s call for a new sacramental materialism?

For those with an inkling of what our conjuncture of nihilistic capitalism has in store for most of us, The Enchantments of Mammon provides us with a version of the Pascalian Wager. Most Marxist versions of this Wager take the form of the adage “Socialism or Barbarism.” The Enchantments of Mammon has added an important twist to this Wager, namely, “sacramental materialism/socialism or Barbarism.”

I’m a moderately sane person, so I know what my wager will have to be, given the structure of the McCarraherian Wager.

A technology is defined as a stock of knowledge prescribing and regulating the combination of certain inputs in order to produce a particular product.↩

The authoritative source here is Joseph Needham (1900–1995), whose multivolume Science and Civilisation in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954–) is proceeding after his death. So far twenty-seven volumes have appeared, the first fifteen of which were written by Needham. Needham’s primary thesis is that several Chinese inventions migrated to the West, including dynamite, the magnetic compass, and the mechanical clock. Needham also argued that once these inventions reached Europe, they boosted its economy, and provided some of the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution.↩

See Kang Chao, Man and Land in Chinese History: An Economic Analysis (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 2–3.↩

See Simon Goodley, “Goldman Sachs ‘Muppet’ Trader Says Unsophisticated Clients Targeted,” Guardian, October 22, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/oct/22/goldman-sachs-muppets-greg-smith-clients.↩

12.15.20 |

Response

Hopeless Romanticism?

The Power and Limits of Eugene McCarraher’s Socialist Imagination

Eugene McCarraher is a shameless Romantic. The reader needn’t take my word for it; the author tells us so himself in the prologue to Enchantments of Mammon. There, having just introduced one of the book’s heroes (John Ruskin), McCarraher informs us that “Ruskin’s courageous and bracing indictment of economics arose from his Romantic imagination, and this book partakes unashamedly of his sacramental Romanticism” (16). Indeed it does. Though Enchantments is many things, it is above all, perhaps, a work of Romanticism, and specifically Left Romanticism. One of McCarraher’s primary aims in the book is to reconstruct a tradition for the Romantic Left, whose opposition to capitalism he claims “has proved to be more resilient and humane than Marxism, ‘progressivism,’ or social democracy” (16). Enchantments is not merely a study of Left Romanticism, however; it is an exemplar of it. The book’s historical-cum-moral and theological critique of capitalist “mis-enchantment” (5); its indictment of other left traditions for their complicity in that mis-enchantment; and its tantalizing evocations of an alternative beyond capitalism all arise from McCarraher’s own “Romantic imagination,” and function to cultivate that of his readers. McCarraher’s passionate rehabilitation of Left Romanticism constitutes, in my judgment, the most generative contribution of his remarkable work. Yet I fear that, politically speaking, McCarraher’s may also be a hopeless Romanticism. For however powerful its vision of a world beyond capitalism, Enchantments of Mammon leaves little basis for believing it might be achieved.

Let me begin with McCarraher’s Romantic conception of “imagination” itself, since it resides at the heart of his project. “Imagination,” for McCarraher as for the early Romantics, means not “a talent for inspiring fantasy, but the most perspicuous form of vision—the ability to see what is really there, behind the illusion or obscurity produced by our will to dissect and dominate” (70–71). A creative faculty of moral and metaphysical (in)sight, imagination both dispels illusion and perceives the deeper reality it conceals or distorts. As such, it is not at odds with “reason,” but complementary to it, and in fact its indispensable partner (71). Romantic imagination is antithetical, however, to the reductive forms of rationality associated with the (unreconstructed) Enlightenment, and with capitalism, which McCarraher variously dubs “mechanical,” “instrumental,” or “pecuniary.” These false forms of “reason” represent grotesquely distorted ways of perceiving and responding to reality.

By contrast, McCarraher contends that the truthful way of perceiving reality is a sacramental one. When not stunted or corrupted, imagination “sees” that “the earth is a sacramental place, mediating the presence and power of God, revelatory of the superabundant love of divinity,” and that “abundance and peace are the true nature of things” (12). This way of viewing the real, which McCarraher terms “sacramental realism,” is constitutively but by no means exclusively Christian. Through the mediation of Romanticism, it has flowed into the wider currents of modern culture (68), informing many who no longer identify with Christianity. Nevertheless, McCarraher thinks Christian theology metaphysically secures sacramental imagination, placing it on firmer foundations and defending it against cooptation (100).

McCarraher’s sacramental realism motivates his critique of capitalism. It also inspires his resistance to “realism” in its more usual sense, as “the Medusa’s head raised to admonish all visionaries to stone.” (622). Both capitalism and so-called “realism” (which often plays partner to the former) radically misapprehend, and disfigure, the true nature of the natural and social world. Both presuppose a false ontology of “scarcity and violence,” which imaginatively and actually transforms human beings into competitive egoists with a boundless desire to accumulate wealth and power (12). This desire to accumulate is capitalism’s essence and driving force, that on which all of its subtler, more “enchanting” features ultimately depend. But far from being simply “bad,” McCarraher suggests, the desire to accumulate itself is actually a misdirected form of our noblest and most powerful desire: the “longing for ‘universal communion’” with God, our fellow humans, and all of creation (12). Capitalism’s demonic power—the power of “Mammon”—derives from the fact that it harnesses this sacred human desire for perverse and self-destructive purposes, such that our fondest hopes become at once “consonant and tragically out of touch with the dearest freshness of the universe” (11). Quite literally, capitalism is sacrilege.

The bulk of Enchantments of Mammon is, accordingly, a multifaceted historical critique of capitalism (whose outlines are discussed elsewhere in this symposium). Simultaneously, however, it is a critique of the Left’s capitulation to capitalism. As McCarraher disclaims, he has written Enchantments “out of a belief that many on the ‘Left’ continue to share far too much with their [capitalist] antagonists: an ideology of ‘progress’ defined as unlimited economic growth and technological development, as well as an acceptance of the myth of disenchantment that underwrites the pursuit of such expansion” (17). The problem of the Left, past and present, is precisely its failure of imagination, its inability to see through or beyond the deceptions of capitalism. The one exception is the Romantic Left, whose members McCarraher’s narrative positions as protagonists and representatives of an alternative road not taken. Their “imagination,” as reconstructed and further developed by McCarraher, serves as the basis for his own anti-capitalist vision. He agrees with Adorno that “only a vantage ‘from the standpoint of redemption’” can even perceive, much less dispel, the mystifications of capitalism (431). And only a vantage from the standpoint of redemption can begin to see an alternative.

What is that alternative? Though the details of McCarraher’s “Romantic socialism” are left undeveloped, its primary elements are clear enough. At its core is the artistic/artisanal ideal of non-alienated labor, which envisions labor as a creative (not merely “productive”) activity. Creative labor enlivens and cultivates, rather than stultifies, the worker and her imagination, and produces aesthetic objects that are beautiful as much as useful (17). More institutionally, McCarraher’s vision of socialism entails direct worker control of production and technological development; abolition of the industrial division of labor, and class divisions; “restoration of a human scale in technics and social relations”; the liberation of “the commons” from private ownership and its restoration to “federated communities;” and a “non-extractive” relationship to nature (17, 677). It also presumably implies some kind of ecologically integrated, “post-growth” economy, such as that envisioned in Juliet Schor’s “economics of plenitude.”1 Such an economy would be premised not on ever-expanding commodity production but on maintaining a sufficiency of fundamental human goods (“goods” here not meaning commodities).

While one might fault McCarraher’s socialist vision for its sketchiness, I rather see its unfinished character as an invitation to further imagination. McCarraher’s largely historical work cannot substitute for the present imagination of its readers, and does not try; what it can and does do is incite, sharpen, and expand it. Both McCarraher’s ressourcement of the Romantic tradition and his Romantic critiques operate in tandem to serve this purpose. If the former provides the “standpoint of redemption” and the constructive resources for contemporary anti-capitalist imagination, the latter dispels the illusions that might otherwise lead imagination astray and trains it to see beyond them, not least by illustrating how others have previously failed to do so. The whole work is, in effect, a pedagogy for Left Romantic imagination.

Received as such, Enchantments of Mammon has much to offer contemporary readers, perhaps especially those of my generation. Speaking personally, as a “millennial” Catholic who was also (not that long ago) an “Occupier” and an activist in the New Economy movement,2 I often felt while reading this book that McCarraher had written it for me. Growing numbers of young people now express a preference for “socialism” over “capitalism,”3 though we are often less than clear on what either term means. Moreover, while many of us, especially on the Left, are taking leave of organized religion, the spiritual “desire for communion” remains. As experiments like “Nuns and nones” reveal, that desire sometimes leads to the most “traditional” sources, just because these sometimes prove the most radical.4 On both counts, McCarraher’s profound retrieval of Left Romanticism, which still remains an unfamiliar tradition for many, is an exceptionally welcome act of paradosis. The times are ripe, and the need urgent, for fresh imagination. The alternative, as McCarraher warns us, is “barbarism and ecological calamity” (17).

But the imagination the present requires is as much practical as visionary. To avoid calamity, to the extent that is still possible, we desperately need insight not only into where we should be going, but how we might get there. And on this score, Enchantments of Mammon falls short. Not only does it fall short; I believe its Romantic anti-capitalism may be prematurely self-defeating. Even as McCarraher articulates a vision and arouses a desire for radical social transformation, the larger cast of his historical and theological imagination threatens to rule out the actual possibility of the socialism for which it hopes. By envisioning “capitalism” as “Mammon,” and premising “socialism” on conversion therefrom, he both makes capitalism too insurmountable and socialism too implausible.

As McCarraher sees it in Enchantments, the history of the anti-capitalist Left is one unending record of failure. The non-Romantic Left’s failure is fundamentally a failure of imagination, which bears fruit in a doomed politics. The American populist movement of the late nineteenth century, for example, failed to “dissent in any fundamental way from the tenets of the capitalist covenant” (280). Instead, it remained trapped within the earlier smallholder capitalist imaginary of “producerism,” while also (misguidedly) admiring industrial corporations’ large-scale forms of organization (“intelligent cooperation”) (268). Its more radical counterpart, the American socialist movement of Eugene Debs, suffered from the same problems; it too “did not and could not serve as a reliable, let alone effective, source of opposition to corporate power” (289). As the latter assessment illustrates, McCarraher’s historical narration often implies these movements’ failures of vision also made their political failure inevitable. Because they were still essentially working within capitalism’s (“Mammon’s”) terms, they merely “postponed a reckoning with the errand’s futility”—the “errand” being the perpetual, yet impossible, American attempt to reconcile “capitalism” and “communion” (258). McCarraher’s verdict on populism and socialism is a fortiori his verdict on the American labor movement, which, even at its apex, “remained well within the bounds of the ‘business mind” (462). Still more is this true of the twentieth century’s many “Progressives” and Left liberals, most of whom never even aspired to move beyond capitalism (e.g., 243, 446). Even the postwar “post-materialist” liberals who sought to transcend industrial capitalism from within were likewise guilty of a “failure of imagination,” and so, too, embarked on a fool’s errand (611).

By contrast, McCarraher’s Romantic Left protagonists do not suffer from the same failure of vision (which is why they are his protagonists). And yet, from the vantage point of practical efficacy, their anti-capitalism too is an abject failure. The inability of most to find any wider hearing is a recurring refrain of McCarraher’s narrative, as is their alienation from the popular movements of their day: most of their contemporaries prove simply too bewitched by Mammon. Though Ruskin was a champion of the working class, the bulk of the working class itself proved “indifferent to or ignorant of his work” (90). Bouck White, the lone Christian socialist “unenchanted” by “industrial progress,” is found “unconvincing or irrelevant” by most everyone else (294). The Catholic Workers are “unable to acquire any purchase on the American moral imagination” for most of their history, apart from a shining moment in the 1960s (478–79). Lewis Mumford (“the American Ruskin”) never even tries to translate his social vision into a “politics,” in part because of his disdain for the labor movement (491). Meanwhile, the Romantic Left’s recurrent attempts at utopian communities typically collapse in comically short order (155, 476). Alternately, they wind up coopted, like Left Romanticism’s cultural and artisanal movements: Arts and Crafts ends up “incorporated” (100, 325); Greenwich Village turns bourgeois bohemian (308); and ’60s counterculture finds itself commodified by “the conquest of cool” (558).

Consequently, one arrives at the end of Enchantments of Mammon with nary a reason to hope “socialism” could ever be anything more than a gleam in the eye of the visionary. The reign of capitalism, of Mammon, seems practically insuperable. All prior attempts to overcome it have proved futile, and almost seem fated to have been. Nevertheless, McCarraher adamantly rejects the neoliberal premise that “there is no alternative,” rightly denouncing such claims as a “war on the imagination” (665). Finding “acquiescence” dispiriting, he agrees with Naomi Klein that “we desperately need . . . ‘a new civilizational paradigm’” (672). But does his account offer any grounds for believing we might actually build a new civilization, much less any credible suggestion for how we might get there?

McCarraher finds some signs of hope in the Sanders campaign, more in Occupy (672–73), and still more in Rebecca Solnit’s survey of “the paradise that emerges from catastrophe” in urban disaster zones (after earthquakes, Katrina, 9/11) (674). Most of all, he appears to see in the impending demise of American empire a unique and historically unprecedented window of opportunity, which the Romantic Left should exploit (677). Yet McCarraher also bemoans “that most of ‘the 99 percent’ want to ‘take back’ the American Dream, not awaken from and definitively repudiate it; no depth or magnitude of failure seems capable of occasioning a fundamental reckoning with the futility of the original [capitalist] covenant” (670). Why, then, believe it should go any differently this time?

At this point, it is worth reconsidering the theological underpinnings of McCarraher’s Romanticism. McCarraher is (selectively) fond of Augustine (12–13), and the longer arc of Enchantments is nothing if not an Augustinian chronicle of our contemporary Rome’s splendida vitia. Yet the Augustine of City of God hardly provides a ground for affirming any kind of radical social change (for the better, at least) is possible in history: until history’s eschatological culmination, the damned mass of humanity is too weighed down by the gravity of sin and libido dominandi. It is no accident that Augustine (again, selectively) was the favorite of Reinhold Niebuhr, that most “realist” of modern theologians. Unlike Niebuhr, however, McCarraher neither manifests Augustine’s willingness to accommodate to empire for the sake of an imperfect “earthly peace” (e.g., by using violence and coercion), nor is he willing to give up on the prospect of paradise here below. Instead, from St. Francis, he draws a commitment to “revolutionary militancy” and “realized eschatology” (678). He accordingly ends Enchantments by affirming that “we can reenter paradise—even if only incompletely—for paradise has always been around and in us, eagerly awaiting our coming to our senses, ready to embrace and nourish when we renounce our unbelief in the goodness of things” (679). The project of anti-capitalism, and of true socialism, is thus founded on a call to conversion. If only we “come to our senses,” and see ourselves as we truly are—if only we renounce Mammon’s wiles—we can build a new civilization.

The problem here is that McCarraher’s Augustinian historical vision gives no grounds whatsoever for hoping that most human beings will come to our senses soon, any more than we have in the past. A small minority might, but certainly not enough to actually create a socialist society. As McCarraher observes of Sanders supporters, most of those who want “socialism” now in essence want a return to the New Deal, not conversion to a radically new way of life (672). Conversely, McCarraher’s own account of his Left Romantic heroes leaves little reason for believing their faithful remnant, even if better organized, could withstand Mammon or their own vices for long. His epitaph for Occupy—“Alas, it seemed that humankind cannot bear too much of heaven”—seems applicable to the entire Romantic Left (673).

McCarraher might, I suspect, take up Ruskin’s line in response: the historical failure of anti-capitalism owes less to sinful human nature than to its stunting under capitalism. The fault resides in “the corruption of morality and sensibility” (and imagination) induced by industrial labor, and now also by consumer culture (95). But in reply I would ask: were human beings en masse really any better before capitalism, or any less prone to libido dominandi? How would one defend an affirmative answer, theologically or historically? And how would such an answer avoid precisely that nostalgia for the Middle Ages which modern critics of Romanticism (and Catholicism) have always suspected lurks under the surface? Moreover, even if a “yes” were granted to the former question, given the state of human beings as we are now after centuries of formation by capitalism, how could most of us be expected to “come to our senses,” apart from some divine intervention of a truly unprecedented variety?

It may be telling that McCarraher also finds in Francis an ideal for “greatness of soul in times of calamity, assuring in the face of disappointment that our desires accord with the grain of the universe” (359). For his Left Romantic vision, disappointment seems assured. But might this not owe as much to the limitations of McCarraher’s “imagination” as to the historical and theological reality it purports to see? In effect, by viewing “capitalism” and “socialism” in such starkly antithetical, totalized, and theologized terms—rather than as contingent, contested, and piecemeal historical projects, with complex interrelations—McCarraher has made the choice both too simple and too absolute. And by imagining capitalism as a false god with the full weight of human sin on its side, he has made “socialism’s” historical failure all but inevitable. Ironically, one might conclude of McCarraher what Ivan Petrella once concluded of many liberation theologians post-1989: their “own analysis of capitalism reinforces the latter’s idolatrous tendencies . . . infusing capitalism with the very same aura of ultimacy, definitiveness, and inviolability they bemoan.”5

Enchantments of Mammon thus leaves us with an eschatologically hopeful, but politically hopeless, Left Romanticism. McCarraher’s sacramental vision may well descry the ultimate nature of things. It occludes, however, any path for better conforming society to it, proving more suited to “resisting” capitalism than to building socialism. We need imagination of another—though perhaps complementary—kind if we are to create a better world today. Nonetheless, whatever forms that imagination takes, it will have much to learn from McCarraher.

Juliet B. Schor, Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth (New York: Penguin, 2010).↩

Gar Alperovitz, “The New-Economy Movement,” Nation, May 25, 2011, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/new-economy-movement/.↩

Stef W. Kight, “70% of Millennials Say They’d Vote for a Socialist,” Axios, October 28, 2019, https://www.axios.com/millennials-vote-socialism-capitalism-decline-60c8a6aa-5353-45c4-9191-2de1808dc661.html.↩

Kaya Oakes, “What Can Nuns and ‘Nones’ Learn from One Another?,” America: The Jesuit Review, September 4, 2018, https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2018/09/04/what-can-nuns-and-nones-learn-one-another.↩

Ivan Petrella, The Future of Liberation Theology: An Argument and Manifesto (London: SCM Press, 2006), 85.↩

12.22.20 |

Response

A Critique of Pure Enchantment

“The American Way of Life embodies a mystery which is common to all men—the mystery of the human spirit,” so the editors of Fortune magazine triumphantly proclaimed in 1951, as Eugene McCarraher unearths. Since this mystery includes the fundamental “metaphysical” truths of Freedom, Prosperity and Progress, they reasoned that all people aspire to the American Way of Life, such that “the question of Americans thrusting themselves on anybody can never really arise” (508). Once the laughter and tears provoked by such a self-serving and self-deceptive legitimation of imperialism have died down for any external observer of US foreign policy, a set of more sober considerations might arise. If life in the United States is unexceptional with regards to freedom from discrimination, enclosure, incarceration, exploitation, grinding poverty, meaningless labour, fruitless competition, mistrust, litigation, self-assertion, narcissistic triumphalism, joyless excess consumption—or any of the other misfortunes or illusions arising from what McCarraher terms a pecuniary metaphysics—how, then, can it mistake itself for the mystery of the human spirit? Why is there such a gap between imagination and reality? Moreover, how can the shiny metaphysical truths of Freedom, Prosperity, and Progress prove so alluring despite the difficulties encountered in attributing any coherent meaning or consistent lived experience to such terms?

McCarraher offers us a frame for such considerations in terms of a concept borrowed from the Romantic imagination, from Schiller via Weber: enchantment. He offers an extensive history of the soul of the America through the lens of its enchantments with material life, covering those mainstream figures enchanted by the progress of capitalism while being especially expansive on those countercultural figures enchanted by alternatives. In both cases, it is an ontological imagination—how one imagines reality—that is decisive. In exceptionally elegant prose, McCarraher conjures before us a procession of entrepreneurs, cultural intellectuals, philosophers, economic gurus, and pious individuals that is itself enchanting: McCarraher displays an America much of which one may love. It soon becomes evident that the notion of “capitalism as religion” is not merely a minor thread in the weave of radical philosophy resurging out of Marx, Benjamin, and Agamben in a neoliberal era to describe the “soul at work,” but a perennial theme of the American imagination, whether capitalist or anti-capitalist, religious or secular. It has regularly motivated and directed efforts to establish paradise on earth. Nevertheless, the era of neoliberalism, which is demonstrably an heir to the long tradition of imagining capitalism in redemptive terms, involves a war on any other use of the imagination, or as McCarraher puts it, “a blitzkrieg against utopian speculation, a mission to sabotage the capacity to even dream of a world beyond capitalism” (665). Resources for such alternatives may be found in the tradition of Romantic modernity, which, whether appealing to imagination, wonder, passionate vision, or sacramental consciousness, “has always been a way of seeing, a perception of some truth and goodness and beauty intrinsic to the material world, a view that embraces without nullifying a knowledge obtainable through the sciences” (675).

In these respects, I would like to confess my wholehearted agreement with McCarraher’s project. Above all, I share most of his sympathies, but I would also admit to an overlap of key influences, agreement with his discussions of those figures with whom I am acquainted and consequently trust in his judgements about those with whom I am not, surprise and wonder at much that he presents that is unfamiliar to me, and gratitude for a reading list for further research. What is really at stake, here, is a matter of seeing, touching and engaging with reality. For the dénouement of modern capitalism in ecological crisis and global populism expresses a loss of contact with reality in our daily lives, a loss of contact I see above all in my own discourse and behavior, but also in that of my colleagues, my university, my nation, and the wider public. Rather than simply inhabiting reality, people largely invest themselves in what they project, a reality conjured up with words and agreements in the forms of socially constructed institutions, procedures, standards, obligations, and objectives. Guided by such projections, even the daily life of scholarship and science may be founded on versions of discrimination, enclosure, incarceration, exploitation, grinding poverty, meaningless labour, fruitless competition, mistrust, litigation, self-assertion, and narcissistic triumphalism, if in perhaps distinctive senses.

Nevertheless, for the sake of furthering the conversation, it may be worth pursuing some critical questions. To what extent can capitalism be identified with peoples’ imaginations of capitalism? Even if a certain production and direction of imagination is an essential component of the capitalist machine, might capitalism itself be an entirely secular reality, best described from the perspective of political economy, despite so many proponents and detractors drawing on the vocabularies of religion to imagine its nature? The frequency of voices imagining capitalism as a religion does not establish that it is indeed best understood in these terms. Linked to this is the knotty question of what actually constitutes a religion, itself a problematic notion invented to name the other of modern, secular reason. Does religion consist in an ontological imagination, a sacralizing of everyday realities? Furthermore, might it not be the case that the common feature of the “American way of life,” in all its mainstream and countercultural varieties, is a certain prioritization of the imagination and its investments, whether this is filled with markets, corporations, machines and commodities, or whether it is filled with smallholdings, utopian communities, and the dignity of crafts, or even whether it is filled with a return to premodern religious orderings of material life? Might Romanticism itself be the perennial accompaniment to modern capitalism, one of its products, yielding enormous opportunities for profit as well as unproductive waste? In other words, can any utopian imagination of anarchist or religious community offer a durable, habitable, sustainable and desirable alternative to the secular progress of speculative boom and bust that constitutes the history of capitalism itself?

Here I might appeal to a French fellow-traveler of the syndicalist, anti-modern, interreligious tradition charted so well for the United States, one whose sojourn in New York in 1942 was too brief to evoke more than a couple of passing mentions in McCarraher’s account: Simone Weil. Rooted nevertheless in a Baconian and Kantian version of modern reason, she offered a distinction between imagination and free work based on the conditions of a market-based society: “People used to sacrifice to the gods, and the wheat grew. Today, one works at a machine and one gets bread from the baker’s. The relation between the act and its result is no clearer than before. That is why the will plays so small a part in life today. We spend our time in wishing.”1 Her diagnosis is that imagination is fueled by the social context of the market insofar as people are first rendered impotent. If what one wants and needs is obtained by money rather than direct activity, then passive imagination replaces real activity engaging with the conditions of one’s existence.2 Projecting and imagining possible futures is no substitute for grappling with the real conditions of existence, the real relations between what one offers and what one receives, or the real limits to possibility that ought to form the object of a science of economics. In this respect, I find those brief paragraphs on political economy near the opening of each section of McCarraher’s book where he summarizes the transitions of the social and material ordering of the American economy in each successive era more enlightening than the metaphysical speculations of the writers within these eras. For political, economic, and ecological life provide conditions and limits that are not always taken into account in imaginations of capitalist or anti-capitalist futures.

What is required, perhaps, is a critique of pure enchantment in a Kantian sense: how might we distinguish between when enchantment expresses an encounter with “the dearest, freshness deep down things” and when it expresses a narcissistic entanglement in the projections of collective imagination? One of the purest examples of the latter adduced by McCarraher would be the psychoanalytic theory of the commodity purveyed by Ernest Dichter, eroding the difference between materialistic and idealistic values, advancing the work of advertising through which objects have a soul or meaning insofar as commodities “permit us to discover more and more about ourselves.” McCarraher successfully draws the inexorable conclusion: “A soul thus projected is redeemed through consumption, a consummation afforded only through the ritual or purchase and the sanctifying grace of money” (563). Imagination, here, is conceived as pure projection: the life of the consumer helps one to know one’s inner self in the form of intentions, investments, or desires. Yet if money is the sole criterion of reality on Dichter’s account, since one cannot know whether one’s wishes, investments, or imaginations are real until one proves it by paying for things, then on Weil’s account it might be the primary criterion of unreality. Following Gerard Manley Hopkins, “dearest freshness” might offer a better criterion of reality that is far from incompatible with an expressive imagination. In this case, as McCarraher helpfully summarizes the Romantic imagination, “imagination was not a talent for inspiring fantasy, but the most perspicuous form of vision—the ability to see what is really there, behind the illusion or obscurity produced by our will to dominate” (70–71). One may therefore posit a difference in kind between enchantments: capitalist enchantment involves projection, where human life is believed to flourish, in the words of James Rorty, as a “parasitic attachment to an inhuman, blind, valueless process, in which money begets machines, machines begets money, machines beget machines, money begets money” (450). In Romantic enchantment, by contrast, imagination may express the real conditions of existence, and human life flourishes through vision of the deep meaning which is already found in things.

What, then, is disclosed by such imaginative vision? If something habitually called “capitalism” structures the real conditions of our existence, what does it begin to look like if one sets aside the metaphysics of Freedom, Prosperity, and Progress that captivate through enchantment, and tries to view it through the lens of an alternative religious metaphysics? Does contemporary economic life continue to resemble a free market or is it shaped largely by enduring obligations? Does economic life continue to resemble capitalism, in the sense of delaying consumption for the sake of investing in greater means of production, or is it an exercise in consumption and wastage at the expense of the conditions of existence that make it possible? Of course, there are many lenses for viewing reality, and many dimensions of economic life that can be made visible. But it seems to me that “enchantment” has its limitations as a metaphysical lens, whether it is a matter of understanding capitalism or religion. For modern economic life, as I see it, is constituted by contingency, crisis, debt, contract, obligation, practical necessity, and uncontrollable feedback processes as much as it is constituted by enchantment, a will to consume, or a will to dominate. Both economic and religious life offer ways of ordering conduct and thinking oriented towards an unknowable future, and both economic and religious life reshape themselves out of an inner necessity or vocation. If we can set aside empirical investigation and analytical dissection in order to display the “dearest freshness” of the metaphysical categories that structure our lives, for good or ill, whether in modern thought itself or in the conditions of modern life, then we might be one step closer to stepping out of a disastrous tunnel vision into the clear light of day. As McCarraher indicates, the overlap between economic and religious life might be just the place to find the metaphysical lenses which can renew our vision of reality.

12.29.20 |

Response

The Importance of Theology for This Book

I have been waiting for The Enchantments of Mammon for a long time, ever since Gene McCarraher published an exciting article by the same name in Modern Theology back in 2005. In the intervening years, McCarraher apparently kept busy; the nearly eight hundred pages of the book reflect a lot of hard work. The thesis—that capitalist ideology is an altered form of theology—is not new; Marx himself said so. Authors occasionally refer to the religious nature of capitalism, but they usually do so in an unsystematic way that allows the reader to assume that “capitalism is a religion” is just a metaphor, thus keeping the boundaries between enchantment and disenchantment, religious and secular, intact. McCarraher is convinced that it is not just a metaphor. What is significant and new about McCarraher’s book is the thoroughness, one might say exhaustiveness, with which he makes his case. Through a detailed intellectual and cultural history of American capitalism—written with McCarraher’s characteristic verve—one sees the aspirations to transcendence, metaphysical implications, and sacramental practices embedded in our economic system. With so much evidence in its favor, the reader cannot help but feel the weight of the argument. McCarraher’s book is a tour de force; even the most resistant readers, if they make it through to the final page, will feel compelled to surrender.

If the argument is persuasive, the implications are profound. It means not merely a revision of the way that we see capitalism, but a revision of the entire narrative of secularization that has marked so much of contemporary discourse. It means that the history of the modern West is not the story of the marginalization of religion, but rather the replacement of Christendom with the hegemony of a new—and in some ways more powerful—“religion”: capitalism. The new dispensation is more powerful partly because we think it is “secular”; we think the functioning of markets is in some sense “natural,” rather than supernatural. To see capitalism as a “religion” would be to expose it to challenge in the ways that all “religion” is now exposed to challenge.

McCarraher’s book can be read in some ways as a more thorough and incisive retelling of the story that Max Weber was trying to tell in his Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Like Weber, McCarraher shows that capitalism emerged in the wake of the Reformation along with a new theological dispensation, a new way of configuring sacrament, vocation, work, and grace. Unlike Weber, McCarraher makes the case that capitalism does not leave theology behind, but rather incorporates it in a mutated form. Theology persists overtly in Christian defenses of capitalism—which continue powerfully among white evangelicals today—and covertly in secular defenses of capitalism, whose proponents—even militant atheists like Ayn Rand—cannot resist using theological language.

Where McCarraher makes especially original contributions is in his thorough archeology of twentieth-century corporate thought. McCarraher examines academic apologies for capitalism, but most interestingly does a deep dive into management theory and in-house advertising strategy to show what the practitioners of American capitalism were thinking. McCarraher makes the case that the emergence of the corporation in the late nineteenth century demolished the foundations of the Protestant capitalist covenant and essentially replaced the church as the location of common action. In management theory, McCarraher finds the “mechanization of communion.” In advertising and consumerism more broadly, he sees a new practice of sacramentality, the conscious animation of inanimate objects that appeals to our deepest longings for transcendence. As everywhere in the book, McCarraher captures the advertising executives saying so in their own words.

As a Christian, however, McCarraher wants to go beyond the unmasking of covert “religion,” which could easily go in a Marxist direction toward the attempted debunking of all enchantment as mere human projection, mere superstructural delusion. We have never been disenchanted, nor could we be, argues McCarraher. We humans have an innate desire to find transcendence and divinity in material creation, the “dearest freshness deep down things,” as McCarraher quotes Gerard Manley Hopkins. Capitalism is therefore not disenchantment, as Weber thought, but misenchantment, in McCarraher’s felicitous term (5). We must and do seek the vestigia of God in creation, though we often look in all the wrong places. “Hence the importance of theology for this book, as I root my affirmation of the persistence of enchantment in a theological claim about the world: that the earth is a sacramental place, mediating the presence and power of God, revelatory of the superabundant love of divinity” (11).

The theological claim is to me the most interesting and provocative claim of McCarraher’s book. Exposing the theology of capitalism is tremendously important, but without a positive theological claim, a Marxist could easily read the book as nothing more than a lengthy confirmation of the ideological character of both capitalism and theology. Without a positive theological claim, an apologist for capitalism meanwhile could simply embrace the sacramental nature of capitalism, agreeing with McCarraher that capitalism is a new form of enchantment. Indeed, McCarraher gives example after example of corporate theorists and marketing practitioners who embrace the new religious dispensation wholeheartedly and shout it from the rooftops. To them, there is no unmasking necessary. McCarraher’s book can only function as a critique of capitalism if capitalism can be shown to be misenchantment, not enchantment, and that can only be accomplished if we have some theological criteria with which to separate good enchantment from bad enchantment.

Nevertheless, McCarraher in this book only makes a few brief gestures toward such criteria. Despite “the importance of theology for this book,” there is not much theology in it, or, to be more accurate, not much good theology in it. One page after staking a claim to the importance of theology to the book, McCarraher admits “However significant theology is for this book, I have relied on a sizable body of historical literature on the symbolic universe of capitalism” (12). In other words, this very long book is full of bad capitalist theology gleaned from cultural history, and not much good theology derived from theologians.