Bridge to Wonder

By

9.1.14 |

Symposium Introduction

9.2.14 |

Response

Theology, Art, and the Beautiful Bridging of Difference

In Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty, the reader is taken on a journey not unlike what Dante experiences in his celebrated La Divina Comedia. Only where Dante is led by Virgil, and later Beatrice, through the depths of the Inferno, up the high mountains of Purgatorio, into the living rose-formed community of Paradiso, in Cecilia González-Andrieu’s text, readers are led across the Golden Gate Bridge to a place of wonder, where an authentic encounter with the divine derives from the full embodiment of what it means to be human. Although hers is not a work of conventional poetry in the way that Dante’s Comedia is, González-Andrieu shares with Dante (and Coleridge, Yeats, Blake, and others) what she explains is one of the “tasks of art”: “to create bridges to revelatory wonder through works of art” (15). The notion of art here employed, as González-Andrieu explains, transcends the “unproductively narrow” view of art that dominates the late modern mind, in which art is more or less synonymous with the fine arts, and instead opens to the premodern idea that art identifies all work of human creativity.

Taken in this sense, Bridge To Wonder, although a work of academic theology, is also and perhaps more so a true work of art, a “living theology” as González-Andrieu identifies it (72), opening the reader to the wondrous origin from which springs both theological inquiry and artistic creativity. There are sophisticated theological arguments made throughout the text, to be sure, but they are constructed upon the concrete foundations of works of art. True to the “method” of the work of art, the arguments herein are “evoked” rather than “proposed.” The name González-Andrieu gives to her unique form of theological aesthetic thinking is acercamiento (90), an intimate connectedness between art and percipient. In these pages, one encounters a truly contemplative theological discourse, energized and sustained by theologically gazing at works of art in order to allow these works to anagogically uplift the intellect to ever-greater dimensions of theological wonder and truth. The book itself presents a kind of gazing, but a gazing that invites, even woos, the reader to gaze with it and beyond it by truly opening the reader’s eyes to the wonder it seeks to explore. And in this sense, the book is truly a bridge to wonder in that it takes its readers to a place of wonder and, once there, frees the reader to explore that wonder anew.

“So this book is about art” (7); “This Book Is Not About Art” (Title, chpt. 2)

What appears in the above citations of Bridge to Wonder as a contradiction is in fact González-Andrieu’s way of getting at what might be called—to borrow the language of William Desmond—the metaxological foundation for all art (see his Art, Origins, and Otherness; Art and the Absolute; Philosophy and Its Others). Art is a phenomenon in between a concrete expressed image and the fuller archetypal referent it aspires to make visible. González-Andrieu’s own identification of art as a bridge fittingly captures this metaxological sense. As a bridge, art is a concrete “this,” something that supports persons who must cross chasms. In this sense, and the fact that the thinking it contains is always founded upon concrete works of art, Bridge to Wonder is indeed about art. However, insofar as art is of its nature referential, always drawing our gaze into itself only to cast that gaze beyond to greater wonder (in the same way a bridge is always oriented toward a place other to the bridge itself), Bridge to Wonder is also about that other place of wonder. Hence, it can also be validly said that this book is not about art. This “between,” or even “metaxologic,” of art is the fundamental ground upon which González-Andrieu takes us on her journey.

Art and the work of art play a fundamental role in the whole of Christian theology since the work that art accomplish is primarily the mediation of revelatory experiences. What we have here in González-Adrieu’s brilliant theological analysis of art is what could be read as the working out of the Balthasarian insight that beauty is a natural form of faith[ref]Cf. Alejandro García-Rivera, The Garden of God: A Theological Cosmology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2009), 4.[/ref]; that is to say, the mystery of faith and the events and experiences it allows find a natural and analogous counterpart in any given person’s experience of the beautiful. The fact that beauty, and by extension art, are never necessarily “religious” phenomena poses a perpetual challenge to any and every theological aesthetic. It is a challenge that makes some form of metaphysical analogy a necessary foundation for theological thinking since the giving over of beauty and art to the world to do with as it wills makes any univocal or equivocal approach to beauty and art inhibiting. This is one dimension where the significance, if not indelible importance, of theological aesthetics for every theological enterprise comes to the fore; it reawakens the theological mind to the need to transcend univocal and equivocal thinking, without dismissing them entirely. And this is precisely what we find in both Balthasar’s insight and González-Andrieu’s working out of that insight in her account of art as a “bridge to wonder.”

If, as Balthasar’s insight contends, beauty can bridge the putative distance between the “natural” and the “beyond-natural,” art performs the work of making this bridge visible to human perception and, consequently, allowing human perception to traverse that bridge, always approaching the wondrous content toward which the art refers. For González-Andrieu, art as a bridge is constituted by its bond to concretes, particularities, and cultures—phenomena that are essential to the work of theological inquiry. Art is a bridge to the past insofar as it serves as a cultural foundation and a community of voices; to the future insofar as it is in a state of perpetually communicating these cultural foundations and voices for posterity. But in order to traverse this bridge, art must be understood in essence as itself a revelatory symbol. The concept of “symbol” in this case identifies an enduring plurivocal (or many-voiced) communication that not only ties a people together across time and space, but also opens them up to a way of seeing. Symbolic seeing enables the objects given in faith to reveal a fullness of reality and to communicate the divine life. In this way, art is understood as the power to transform what is given into something new, to infuse the given—the gift of existence in all forms—with the image of “bridged” or “bridging” creation; that is to say, creation striving after transcendence, striving after its Creator.

Art can also be understood as the power to preserve cultural identity, not as some hegemonic triumph of one cultural form, but as the very possibility of every particular cultural identity. As the bearer of cultural DNA, so to speak, art preserves cultural identity as a living memory, as a way that overcomes time’s fragmenting of the past from the present and future. “Art as the carrier of tradition,” explains González-Andrieu, “speaks to a community and thus can be an effective container and carrier of a community’s sense of God, of its theology” (109). Art is the power to unite the disparate elements of time as those elements are concretized in symbolic forms. This power to unite these otherwise disparate elements, however, only bears efficacy when art as a bridge remains oriented toward the other place, toward the wondrous content to which it always and necessarily refers, and hence out of which it originally sprung. When these disparate elements are not preserved in the communal act of symbolic sharing that constitutes the power of art, which can occur when the original wonder that inspired the works is forgotten, lost, or ignored, these symbolic forms retreat into the transience of time bringing about cultural, and personal, disintegration. “A culture that shares no symbols,” writes González-Andrieu, “would lose its ability to think diachronically with any depth” (56). The loss of this depth is coincident with the disintegration of meaning that shines in all works of art, leaving them with nothing more than an ornamental status.

Here is what might be considered an argument from beauty that touches the discursive impulse in human thinking (as all arguments somehow must) but that does so by transcending that impulse in its communication of a surplus of artistic intelligibility. It is, in a strange irony, what Kant knew as the “physico-theological proof,” which commands the greatest respect because it follows the natural movements of our mind,[ref]Cf. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (London: G. Bell, 1884), A623–4, B651–2.[/ref] though here we might rather say “the natural movements of the human person in her wholeness.” González-Andrieu’s theology of art is, among other things, an argument against the idea—commonplace in our late modern world because it derives precisely from modernity’s mythology of itself and its past—that values and the practices that seek values are simply free floating in the fabric of nature, and can therefore be discerned, acquired, and sustained without any appeal to the cultural, and therefore religious, contexts out of which they originate. That is to say, it is an idea rooted in the belief that only when we really release the pressure of the particularities of religion and culture—so recalcitrant as they are to the purity of universal reason—can our eyes find the clarity necessary to see value and appreciate beauty. This is, of course, nonsense; values and beauty are never neutrally there, but only ever derive from the particularities of a cultural ethos and aesthetic. The idea that values or works of art can simply pass from generation to generation with little to no awareness of their originating contexts is already itself a categorical condition that, rather than giving values or art works greater visibility, significantly obscures them. As González-Andrieu rightly explains, “If the spring from which art flows is devalued (in this case by defining Christianity as speculative, ideal, or imaginary), the art flowing from it is also devalued” (71). In this sense, art as such is one very powerful antidote to the disintegrating force of much post-Enlightenment thinking, or “impoverished modern rationality,” as González-Andrieu calls it (75).

In a word, then, art is the power of integration, personal as well as communal. And what is being integrated across the decay of time is what Alejandro García-Rivera called the “community of the beautiful.”[ref]Cf. Alejandro García-Rivera, Community of the Beautiful: A Theological Aesthetics (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1999).[/ref] It is a community gathered and elevated by the power of beauty, which is to say, by the very power of the God who enters into human culture himself, both as a personal form in the incarnation (the Son) but also as artistic/cultural forms in every act of human creativity (the Holy Spirit?). Beauty transcends all human categories, resists all human conceptions, and is recalcitrant to all attempts to confine or define. Yet it lives, thrives, and inhabits the particular, the concrete, the everyday. Taken together, these two dimensions of beauty convey the often painful the fact that, as Socrates proclaims at the end of the Hippias Major, “all that is beautiful is difficult” (304e). Beauty attracts and entices intellectual effort, gives itself to this effort, and then—like a mysterious lover—withdraws from that effort in order to further stimulate and energize it. But theology is nothing if not about participating in building the community of the beautiful. It must, therefore, look to the particular, the concrete, and the cultural since only here do human beings discover, receive, and co-create their humanity with God and one another. The community of the beautiful is, then, an eschatological community that embraces both heaven and earth. For this reason, the power that the work of art performs can be rightly conceived as a “bridge to wonder” insofar as it integrates, or “marries,” heaven and earth.

Beauty As Difference

Art’s integration, however, depends upon the beauty that derives from difference as such. As a method, theological aesthetics integrates a plurality of voices (or discourses) on a given subject as its work of commun-ifying joins this plurivocity together. It is a method “centrally concerned with expansion and collaboration, with perspectives and also closeness” (133). One of the benefits of art, recognized so keenly by González-Andrieu, can be found in its capacity to allow, even invite, itself to be perceived in a diversity of ways. “[T]he greater the work of art,” she writes, “the more ‘polysemantic’ it should be” (91). Art opens a way of engaging the otherness of difference beyond “forced homogeneity” (univocity), or “confrontational polemics” (equivocity), and instead invites the mode of metaphysical analogy that González-Andrieu calls “thoughtful and respectful engagement”: “This third type of engagement does not minimize differences or difficulties, nor does it blow them up into a polemical frenzy, but rather notices them as productive sites for generating new knowledge” (63).

How does new knowledge come about? It begins by providing a new way of seeing; a kind of seeing that integrates the “headiness” of discursion, conception, and determination, with the “heartiness” of love, desire, and imagination. But in order for art to grant such a way of seeing—and thus knowing—it must first destabilize the knower especially if her forms of knowing have become too embedded uncritically in certain strands of modern rationality. As González-Andrieu keenly recognizes, there is a comfort in our late modern ways of knowing that stress the authority of empirical evidence, the reliability of conceptual closure and definition, and the utility of material mastery (76). Today, many seem to shower in Kant’s sweat, so to speak, generated as it was from the discomfort of reality that does not conform to our categorical modes of thinking. How can such thinking possibly engage the kind of intelligibility that inhabits a realm of mystery? Art in general, but especially what González-Andrieu calls “truthful works of art” (69), serves to destabilize these comforts. It does so not through intellectual arguments—that is, not by entering into the sameness of that comfort—but through the difference of sensuality, where intellect and world first confront one another. This is to say, art’s otherness, art’s difference as art, awakens us from our modern rational slumber, awakens us to a way of seeing and therefore knowing that integrates heart and head, spirit and matter, love and thought.

Art’s power to displace is not effective only against certain forms of modern rationality. It can also displace the very religious categories, concepts, and ideas that it often excites, showing them to be incomplete, even incoherent. This enables a rebuilding, a renewal, or a reawakening to a fuller sense of what these religious elements first sought. Art does both services almost spontaneously inasmuch as its very nature is, what González-Andrieu calls, an “interlacing” of difference and otherness (88ff.) Interlacing is the notion that she uses over and against the notion, prevalent today within many forms of interdisciplinary studies, of intersecting. Where the notion of intersecting, or an intersection, emphasizes a point of encounter with otherness and difference forever proceeding away from this point, interlacing involves a plurality of encounter points that continually merge and wind around one another like the strands of a braid. To put it another way, intersecting calls to mind the Hegelian mode of dialectic, where difference and otherness are really only points of encounter along the way to self’s higher identity, while interlacing is much more akin to Desmond’s metaxological mode in which difference and otherness are continually constitutive of the self and the self is continually constitutive of that difference and otherness.

This metaxologic of art’s interlacing is where a new kind of knowing arises. Knowledge in this case is an act of communal intermediation where knower and known enter into a mutual self-offer. The knower is not merely a passive receptacle of extra-mental data, nor a subjective constructionist burdened with the task of generating the appropriate categories and concepts to make things knowable. Rather, the knower is a participant in the coming-to-be-knowable of a given object. Understood through González-Andrieu’s theology of art, every knowable object gives itself to be known in a rich plurality of ways. Much like the act of artistic interpretation, knowing is bound up with both the object’s self-disclosure and the knower’s own critical self-awareness. But more than that, there is an event happening in between these where the excess of a thing’s knowability invites the knower to higher levels of its excess intelligibility. To see this excess of intelligibility requires more than the light of the knower’s initial starting point. It requires a community of lights deriving from a variety of sources, all of which can be gathered by the knower in her subjective perspective. “In this,” explains González-Andrieu, “what happens as we experience art is a knowing of a different order that ‘transcends mere subjectivity, and draws the mind toward the thing known and towards knowing more’” (70).

For this reason, art offers something much more than works for aesthetic contemplation. It provides a power to bring unity and plurality, sameness and difference, into a non-limiting harmony that, rather than compromising either plurality for the sake of unity or vice versa, allows each to compliment and enhance the other in an act of revelation. Insofar as art is “a work of human making that complicates the natural,” and is “a gift that speaks to a community because it captures the spirit of that community” (111), art conveys a beauty that, in pleasing and delighting us, teaches us about our own beauty. “Our own” here indicates a unique forming of beauty that, as unique, is bound up with our own difference(s), indeed is constitutive of these differences. And, in the light of beauty, these differences become moments of integration and community rather than isolation and atomized individuality precisely because they are beautiful. “In this,” concludes González-Andrieu, “we might understand art as having the capacity to return meaning to one’s humanity”(113). The power of art to reveal is bound up with art’s embodiment of unity-in-plurality, its many voices singing through the unity of its concrete form. In making us aware of an “ever-receding ‘more’” rather than conveying one single meaning, art reveals its capacity to function theologically.

Looking Back Over the Crossed Bridge: Some Reflective Inquiries

I cannot overemphasize the delight elicited in crossing González-Andrieu’s Bridge to Wonder. This is a book that I would strongly recommend to all readers, but especially those theologians who are curious about this new field of theological aesthetics. As I myself reach the end of this bridge—where “end” indicates not the cessation of the journey but the stepping into the wonder to which it has lead me—and as I look back upon the bridge that has led me here, I would like to raise three questions: one rather irrelevant question about Plato and his role in bridge building; a second question concerning the inherent equivocal sense of art; and a third and final question about what we are to do with the other side of the bridge that we have left.

Although the objections raised against Plato throughout Bridge to Wonder are certainly not invalid in themselves (that is to say, relative to the internal content of The Republic, and the social dimension that González-Andrieu emphasizes), relative to a more comprehensive account of Platonic thinking some might find this treatment not only dissatisfying, but also somewhat puzzling. If ever there was a philosopher who could be considered the pioneer of building bridges to wonder surely it is Plato. His whole way of thinking, his whole way of perceiving the world, is everywhere imbued with wonder. In fact, one could argue that it is too filled with wonder, which is why Aristotle rejected some of Plato’s most significant ideas (the theory of forms and the theory of participation to name the most significant). Yet given the two, González-Andrieu chooses Aristotle’s companionship rather than Plato’s in crossing her bridge. To be sure, Aristotle is a fine companion for a variety of reasons, and my question is not directed at his presence. Rather, it is directed at what in my view is a false choice between these two great thinkers. As Albert the Great once remarked in his Metaphysics, both Aristotle and Plato are necessary to perfect a person’s thinking: et scias, quod non perficitur homo in philosophia nisi ex scientia duarum philosophiarum: Aristotelis et Platonis (I:5:15).In the context of a method that aspires to integrate rather than separate, to synthesize rather than atomize, to collaborate rather than isolate, the treatment of Plato in this otherwise remarkable work appears out of place.

This is not to say that the criticisms of Plato are unwarranted, but rather to say that even given Plato’s shortcomings, why not treat him with the power of theological aesthetics? Why not integrate his thinking by assimilating his own bridges to wonder? Yes, he does have many critical things to say about art in The Republic, but what about what he says elsewhere? In dialogues like the Sophist, the Gorgias, and the Phaedrus, one finds there a fuller sense of art that certainly seems to correspond to González-Andrieu’s own desire to explore a more premodern sense of art. Is his condemnation of the arts in The Republic so comprehensive as to render what he says of art in these dialogues irrelevant? In both the Sophist and the Gorgias, Plato’s scorn for art seems more directed, not at art per se, but at the way in which artists can stunt human wonder by absorbing it into the artist’s own vision rather than toward the realm of true forms. In The Phaedrus, Plato distinguishes between the kind of art dependent upon human skill and that which derives from the divine influence (mania as he calls it), with the former receiving Plato’s typical condemnation and the latter receiving praise (250b-e).

The more generous treatment of art in these other dialogues should at least give us pause to consider the ways in which Plato contributes to bridge building and symbol making. We could also consider the bridges and symbols that bear his architectural signature: the image of the Sun, the Cave, the realm of ideal forms—are these not also bridges that take us to wonder? It seems that, rather than leaving Plato behind at the foot of the bridge, it would have been possible to grant him access provided he leave behind some of his anti-artistic baggage, so to speak. But as I noted, this is a very minor quibble with an otherwise magnificent work of theological aesthetics.

Secondly, I’d like to raise a question concerning the equivocal sense of art and ask more precisely where this equivocal sense fits into González-Andrieu’s theological account of art? Perhaps the best way to articulate the equivocal sense of art can be found in the pages of William Desmond’s God and The Between: “The artwork is always, in some measure, equivocal. It allows the promise of fecundity that comes with creative ambiguity. Without this fecundity, there is no festivity, no generation beyond ourselves, no self-transcendence. A condition of the continuation of our self-transcending is the continuation of the fertile ambiguity” (139). The reason for raising this question is not to overcome this equivocal sense for the sake of some more univocally determinate sense of art. To the contrary, I share Desmond’s idea that art’s equivocal sense is an essential dimension of all art, allowing for the excess of its interpretive content as well as the very fruitfulness of human self-transcendence. My question is directed to González-Andrieu’s primary image of art; how does this idea of art’s equivocal sense fit into the image of art as a bridge? It seems that in the context of this image, one could read the two points being bridged as the equivocity that art mediates. Or one could view the bridge itself in an equivocal way as being either an artwork itself or a medium through which we are taken to a realm of artistic wonder. There is also the chasm over which the bridge stands, exhibiting a relation to the bridge itself that seems equivocal—do the chasm and the bridge constituted an unmediated difference? Can the chasm’s otherness be mediated? Or is it simply that the chasm represents that dimension of art that will forever be recalcitrant to art’s integrating power? Again, these are just questions that this remarkable work of theological aesthetics has provoked for me.

This brings me to my final question, which is related to the second question: in the context of the equivocal sense of art noted above, and in the context of González-Andrieu’s image of art as a bridge, how ought a theological aesthetics think the “space” that is being left behind when the bridge is crossed? Or, to put it more directly, what becomes of the side we are leaving? This question may make more sense when located in the Western theological tradition as represented by Augustine and Dionysius the Areopagite. Both figures shared a sense that the world and everything in it serves as a way to God. However, there is a discernable difference regarding what happens to the world once one is on the way to God. For Augustine, it could be argued that things in the world are like ladders that, once ascended, ought to be kicked out from underneath a person. For Dionysius, things in the world are rather like doorways that one must pass through but that always continue to constitute the “space of wonder” just as a doorway to a cathedral continues to stand as a constitutive element of the cathedral once it is passed through. Bridges are meant to be crossed, and the purpose of crossing is usually to leave another place behind. So, in light of this, I wonder what is the place that is being left behind, and whether it ought in fact to be left behind? How does this place then relate to the place of wonder toward which the bridge takes us?

As I look back over the bridge that I have crossed with González-Andrieu, these are the questions that beset me in this new place of wonder. I ask these questions with immense gratitude for being taken across this bridge. Bridge to Wonder is a remarkable work of theological aesthetics, and one that I hope wins the influence it more than merits not only among theologians but for all those who share Augustine’s famous dictum: “our hearts, Oh Lord, are restless until they rest in you.” Building bridges to wonder may be the most important way that we can truly come to rest, which means that as theology proceeds upon its path of development, art could become its most important ally.

9.7.14 |

Response

What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Art and Revelation?

Will Beauty Save the World?

The slogan “Beauty will save the world” is increasingly invoked by religious believers these days. What this might actually mean is not given much thought, as is the case with most reflex responses. The words come from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. The Christians who use the phrase usually think the words issued from the lips of the story’s main protagonist, Prince Myshkin. Nothing could be further from the truth. Dostoevsky’s intended ambivalence toward the phrase is signaled by the fact that Ippolit and Agalya only attribute them to the Prince, but we never hear him using them. The words would be suspect even if they issued directly from the Prince’s lips, because Dostoevsky considered Myshkin to be his biggest authorial failure because the character’s moral beauty and innocence were too weak to save anyone. If anything Myshkin was an example of the “beautiful and lofty” Romantic ideals Dostoevsky fiercely lampooned in Notes From the Underground. And yet isn’t there something beautiful and forcefully prophetic about Alyosha, or even Ivan, in The Brothers Karamazov?

The Catholic Imagination

Cecilia González-Andrieu sets out to explore the many ambivalences of the beautiful in her Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty. On the margins, the work positions itself in the long line of Catholic Studies monographs inaugurated by David Tracy’s The Analogical Imagination and continued by such works as Greeley’s The Catholic Imagination, Pfordresher’s Jesus and the Emergence of a Catholic Imagination, Murphy’s A Theology of Criticism, Heartney’s Postmodern Heretics, and even Massa’s Anti-Catholicism in America. The accent of all these works falls upon stressing Catholicism’s incarnate and sacramental imagination that, as González-Andrieu says, in its best moments “has historically meant to encounter ‘God in all things,’ as taught by St. Ignatius of Loyola and beautifully lived by St. Francis of Assisi” (110). What the author has in mind are not only extraordinary mystical transports, although those are included as well, but rather Catholicism harnessing “the force of the imagination to lift the community’s gaze toward God in soaring cathedrals and haunting music. But beyond this, in its sacramentality, [Catholicism] has also lifted the ordinary—water, wine, bread, oil—seeing in it another dimension that allows us entry into God’s imagination” (110). In Catholic Studies literature these emphases are frequently contrasted with a more dialectical Protestant imagination that tends to see the relationship between God and his creation in more antagonistic terms; these authors frequently cite Barth’s intersecting lines. The scholarship of Matthew Milliner and William Dyrness has helped to bridge the chasm between these two ideal types by unearthing the analogies between dialectics of the Protestant imagination and the analogies of the Catholic imagination.

Even if the Catholic imagination (at its best) is calibrated to see God in all things González-Andrieu does not ignore the ambivalence of beauty. For example, mystical and ordinary beauty can be used to deaden the senses to real suffering in the world; one can come away from exploring the Vatican Museums or from participating in the most exquisitely staged Latin liturgy with only a great appreciation of their formal perfection, but without having been hearing the call to embody Christ’s mercy. Kitsch, with its own brand of beauty, can sometimes make better contact with God’s beauty than the more expensive artefacts as González-Andrieu’s account of a competition between two Lutheran congregations in one church demonstrates. One congregation was mostly white middle class with an exquisite tree with its expensive, tasteful, but anodyne decorations. The other Lutheran congregation was a mostly migrant-worker congregation that still retained the Catholic tradition of decorating its tree with a posada scene (one that recounts the Holy Family’s return from Egypt and its search for an abode) in such a way as to advert to the scandal of its poverty and migrancy (123–29). Interestingly enough, the phenomenologist Jean-Luc Marion also comes out in favor of kitsch for similar reasons in his Crossing the Visible. He believes kitsch prevents us from idolizing the formal perfection of a sacral artwork, because its bad taste of reminds us that the sacral artwork’s main work lies in pointing us beyond toward God and his image and likeness.

Zounds of Beauty

Ultimately, beauty receives an implicitly Christological redirection throughout Bridge to Wonder. This redirection is perhaps best summarized with the following, “What is beautiful can be so most powerfully in that it wounds us and directs us to the longing our wounds reveal. In this beauty that is most fully revealed in Christ, the good and true are woven together and made sensible, so we may want them, grasp them, inhabit them, and love them” (24). In this rich formulation there is an implied critique of Jean-Luc Marion’s teacher, Levinas, and his prioritization of ethics over ontology: the Other does not immediately (terroristically as some might say) evoke a response of compassion and pity. First of all, as Rene Girard has argued especially forcefully in I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, it requires the mediation of the Christian message that first placed the victim at the center of our value systems. Second, art can serve as such a tool of mediation for this Christian inversion of values because it visually depicts the consequences of our victimization mechanisms.

Bridges to Wonder is a testament to the strength of this mediation through its many detailed discussions of the contemporary art scene. The lasting power of the Christological mediation is especially apparent in the several chapters González-Andrieu devotes to the exhibition Seeing Salvation, which was a surprising hit at the National Gallery in London. The exhibition featured mostly Renaissance paintings, a few contemporary paintings, and the unveiling of Mark Wallinger’s Ecce Homo in Trafalgar Square. These mostly traditional pieces of art were on display more or less at the same time as the Royal Gallery’s Apocalypse exhibition that featured the controversial sculpture La Nona Ora that depicts Pope John Paul II being hit by a meteor. Surprisingly, despite the critical acclaim for Apocalypse the less critically acclaimed Seeing Salvation exhibition drew five times more visitors during its run (48–50).

Revealing Orthodoxy

Why is this the case? González-Andrieu speculates that the Seeing Salvation exhibition was able to hit deeper by tapping into the Christological (Christian and Catholic) imagination that has shaped the West. The issue of how much art has helped the Christian revelation penetrate the Western imagination, and how widely intelligible revelation remains, is another key strand in the argument of this book. Bridge to Wonder starts out with a meditation upon Avery Dulle’s Models of Revelation, which zeroes in on how much contemporary theological discussion have centered upon the explication of revelation, have taken revelation for granted, instead of asking the question of what revelation is in itself (11–17). This is a probing question that begs for an answer. González-Andrieu is right on target for highlighting it from the beginning, but the analysis of her book does not answer it directly and systematically enough. The passage we cited above were we are told about beauty (and ultimately art) leading us to “what our wounds” reveal is the only place in the book where there is an approach toward making a Christological connection and redirection for our understanding of how art works with revelation. The rest of the book rarely makes the same connection, because its discussion of revelation, a question the author put at the forefront of her book, is too generic, not Christological, Trinitarian, just plain explicitly theological enough.

For example, we are told that “For a fruitful relationship to exist between art and religion, art has to be cut loose, as it were, from the need to teach by illustration, and allowed to embody these types of rich experience, multiple and varied.” She continues, “Art cannot thrive if it is subjected to the perception that it is ‘controllable’ and held to doctrinal standards of orthodoxy” (82). But the example given earlier of art’s “uncontrollability” from an Ortega y Gasset story about a non-believer being struck by the “pandemonium” of a medieval cathedral complicates the following dichotomy: “Didactic art could never accomplish this pandemonium” (77). We are told, “What Ortega recounts is not a lesson, but an interrogation, a living ‘commotion’” (77). What Ortega recounts in fact is the experience of a practical modern Spanish man encountering the medieval cathedrals that were the sites of didactic art par excellence! They were the Bible set in glass for the mass of illiterate peasants of the times. The choice need not be a dualistic either/or between orthodoxy and creative artistic pandemonium.

After all, orthodoxy, just as much as the biblical stories it derives from, tells the wild story of the God-man in all its messiness. In fact, orthodoxy is a protection against the all too neat rationalizations of heresy, which take what they deem to be the palatable parts of either the Bible or doctrine and blow them out of proportion to the exclusion of everything else. We all too frequently ignore how much orthodoxy’s function is to remove these fences so that theologians with different temperaments—Aquinas and Bonventure, Rahner and von Balthasar, Anscombe and Day—can run the fields freely. At a more than subconscious level González-Andrieu is aware this is a false dichotomy, because she goes out of her way to build up her argument for art as a way to God with many papal pronouncements. Throughout the book we encounter many prophetic passages from John Paul II, from Benedict XVI, and, perhaps most surprisingly, from Pius XII. The much-maligned Pius, a thinker most avoid on principle, gets the last papal word in the closing pages of Bridge to Wonder: “Whatever in artistic beauty one may wish to grasp in the world, in nature and in [humanity], in order to express it in sound, in color, or in plays for the masses, such beauty cannot prescind from God. Whatever exists is bound to [God] by an essential relationship” (163). Here the boundary between nature and grace, plus between art and the hierarchy, remains continually porous through an essential relationship.

Squaring it All with Postliberal Hermeneutic Circles

This essential relationship is then illustrated by González-Andrieu with an analysis of the Buffalo cave-paintings in Lascaux. These most ancient artworks look deceptively naturalistic in execution, but we are told to look more closely, “at Lascaux we perceive the intense aliveness of human artistry, not only in the painting of the shaman, but in the religious ritual, the act of beholding God that the shaman seems to be involved in, as we note his bird-headed staff and exaggerated body position.” Thus, from one of the oldest artistic representations known to humanity we glean the insight about the “inseparability of what is art and what is religious” (163–64). González-Andrieu speaks about the “interlacing” between art and religion, yet, many parts of her account suggest the ties between the arts and religion are much stronger than that.

I would like to go even a step further, and argue that throughout Bridge to Wonder, in its interpretations of plays, literary texts, and paintings (ancient and contemporary) we are continually exposed to the primacy of orthodoxy for hermeneutics. Even when the book wants to mark out a prophetic space in which “art expands what we can see and imagine beyond the boundaries prescribed religious statements” we are soon brought within the ambit of orthodoxy. And so even though prophetic “radical newness may manifest itself outside of proscribed ecclesial structures and what may at any particular point in time be considered orthodoxy” it is still circumscribed within the larger from of the development of doctrine. Because this “potential for renewal has been a central feature of the Judeo-Christian tradition since its beginnings.” There is nothing controversial about such an assertion since long before Newman wrote his An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, Christians were aware that their understandings of revelation necessitated recalibrations, sometimes radical ones. After all, they (like the biblical authors and so on) were the ones making those very recalibrations! The recalibrations constituted new forms of orthodoxy.

In the end, perhaps there is no need to posit a dualism, or even an interlacing, between prophetic art and orthodoxy theology? They seem to be instead involved in a hermeneutic circle that has a lot more in common with the post-liberal theology of George Lindbeck than anything else. I must admit The Nature of Doctrine has always puzzled me with the way it proposed understanding the grammar of a theological tradition through its enactment. I’ve always wondered, “But what about conversion?” How does someone who stands outside that grammar ever enter into it? Reading González-Andrieu has suggested one possible solution to this problem: post-Christian societies remain within this hermeneutic circle, which is why an exposition like Seeing Salvation could be a) intelligible but also b) very appealing to audiences who could pass for being non-religious. Nietzsche constantly complained about the lasting presence of theological categories in the most unlikely places and he probably continues to turn in his grave during these postmodern times. Girard would point out how much we still, in a very Christian manner, all agree that the victim is perhaps the only value all can agree upon in a globalized world.

Breadsticks and Theological Yardsticks

Finally, Bridge to Wonder demonstrates the primacy of theological hermeneutics in its account of the controversy at Assy. The church in the little French town was the pet project of a Dominican, Marie-Alain Couturier, who wanted to turn it into a Mecca of modernist art. The priest saw this project both as an attempt overcome the chasm between modern art and religious people and as an attempt to get modernist artists to get interested in religion. The project was a critical success (by now you, the reader, should be weary of these sorts of victories), however, the parishioners rejected most of the art tout-court. The worst was Richier’s crucifix, which looked like a pair of overbaked breadsticks, even worse, some of the parishioners thought it was literally demonic. The artwork’s lack of appeal, according to González-Andrieu, had to do with the artist’s theological ignorance of basic Christian theology. Richier is cited as saying, “[her crucifix] had no face because God is the spirit and faceless” (146). Yet, according to González-Andrieu, this should have opened the door to a teaching moment. A properly theological-reading—one that eschews dualistic divisions between nature and grace, theology and art—of the crucifix by the parishioners would have recognized the deep wounds of (post-) modern humanity and its tenuous beliefs in vaguely spiritual and faceless deities to which nobody can, nor ought to, dance.

In the end, it seems that the overcoming of such dualisms wins out as the stronger motif in this challenging book. Something more theologically robust needs to take the place of the interlacing art and theology. I, for one, would be very much interested how the author treats the crucifixion (that thing through which art “wounds” us) in relation to art in a way that answers the question that opens up the book: What do we talk about when we talk about revelation? And how does the resurrection fit into this picture? Need beauty always wound? The answers to all these questions would go a long way toward going beyond Dostoevsky’s vague sketches and better explain how beauty, in a Christian theological understanding, might save the world. I hope Bridge to Wonder will be a springboard to books that deal with these questions more closely, just as evocatively but more systematically, without setting up dualistic barriers (even if they are mostly in between weaves) between art and theology.

9.10.14 |

Response

The Enchantment of Lightning

Why Some Bridges to Wonder are Stronger than Others

Cecilia González-Andrieu’s Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty begins with a personal meditation on the Golden Gate Bridge as a metaphor for her project of uniting the disparate worlds of art and theology. I take her opening reflection as an invitation to respond with a similar mediation from a different American coast—reflections that have caused me to reconsider aspects of my original review of her book.

Growing up in New Jersey, I frequently crossed the Delaware River over the baby blue Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Arriving on the Philadelphia end, I remember being puzzled by the 60 ton, over 100 foot tall “Bold of Lightning,” a sculpture by Isamu Noguchi. It sparked neither awe nor delight in me as a child, even while the actual lightning it evoked often did. Like any American schoolchild, I was dutifully catechized with the wit and wisdom of Benjamin Franklin, and it later dawned upon me that the key at the base of the sculpture, and the kite at the top, made it a testament to Franklin’s iconic experiment, one that caused Immanuel Kant to dub him our “Modern Prometheus.” In the famous act that perfectly encapsulates modern ambitions, Franklin domesticated lightning in the name of reason and progress. Relating this story was as close as public schools could get to the Lives of the Saints, and Noguchi’s sculpture merely proffered the accompanying shrine.

Growing up in New Jersey, I frequently crossed the Delaware River over the baby blue Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Arriving on the Philadelphia end, I remember being puzzled by the 60 ton, over 100 foot tall “Bold of Lightning,” a sculpture by Isamu Noguchi. It sparked neither awe nor delight in me as a child, even while the actual lightning it evoked often did. Like any American schoolchild, I was dutifully catechized with the wit and wisdom of Benjamin Franklin, and it later dawned upon me that the key at the base of the sculpture, and the kite at the top, made it a testament to Franklin’s iconic experiment, one that caused Immanuel Kant to dub him our “Modern Prometheus.” In the famous act that perfectly encapsulates modern ambitions, Franklin domesticated lightning in the name of reason and progress. Relating this story was as close as public schools could get to the Lives of the Saints, and Noguchi’s sculpture merely proffered the accompanying shrine.

One might think that the other Philadelphia bridge I grew up traversing, named after Walt Whitman, would offer an alternative to Franklin. Having answered Emerson’s call for a native poet of genius, surely the bard of Camden would generate a more expansive view of lightning. Indeed, the theme of electricity suffuses the entirety of his poetic corpus. But having once apprenticed myself to Whitman’s intoxicating celebration of electric selfhood, I—lacking his native capacities—blew a fuse. Whitman’s erotic lightning is, I’m afraid, as dangerous as it is powerful, and his description of urban democracy eclipsing the weather itself seems, in retrospect, equally naïve. “I have witness’d the true lightning,” he exclaims, “I have witness’d my cities electric, I have lived to behold man burst forth and warlike America rise . . .” It is difficult to walk through Whitman’s native Camden with this sense of urban wonder intact, or to read his adulation of warlike America today without considering military ventures less noble than the Civil War.

One might think that the other Philadelphia bridge I grew up traversing, named after Walt Whitman, would offer an alternative to Franklin. Having answered Emerson’s call for a native poet of genius, surely the bard of Camden would generate a more expansive view of lightning. Indeed, the theme of electricity suffuses the entirety of his poetic corpus. But having once apprenticed myself to Whitman’s intoxicating celebration of electric selfhood, I—lacking his native capacities—blew a fuse. Whitman’s erotic lightning is, I’m afraid, as dangerous as it is powerful, and his description of urban democracy eclipsing the weather itself seems, in retrospect, equally naïve. “I have witness’d the true lightning,” he exclaims, “I have witness’d my cities electric, I have lived to behold man burst forth and warlike America rise . . .” It is difficult to walk through Whitman’s native Camden with this sense of urban wonder intact, or to read his adulation of warlike America today without considering military ventures less noble than the Civil War.

Can contemporary art re-enchant lightning in the way that Franklin and Whitman could not? This is a question considered in Jeffrey Kosky’s provocative publication The Arts of Wonder: Enchanting Secularity. Published just after González-Andrieu’s similarly entitled exploration of art and faith, Kosky’s aim is to “break the necessary condition between secularity and disenchantment.” Kosky even begins by lamenting the world beneath Franklin’s “second sun.” “We have inherited the clear and distinct world of things revealed by the apotheosis of electricity. . . .Nothing now escapes the light.”

Retreating from a world plagued by what Michael Serres dubbed “cancerous growths of light,” Kosky takes a pilgrimage to “the ultimate work of Land Art,” contemporary artist Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field. Kosky’s failure to actually witness lightning during his visit (as so few pilgrims do), is compensated for with rich reflections on everything from the gospels to Aby Warburg to meteorology. In his attempt to re-mythologize lightning, Kosky fruitfully infers that modern critics may need to draw upon religious vocabulary, which could have the effect of prolonging encounters with the many works of art he explores.

Retreating from a world plagued by what Michael Serres dubbed “cancerous growths of light,” Kosky takes a pilgrimage to “the ultimate work of Land Art,” contemporary artist Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field. Kosky’s failure to actually witness lightning during his visit (as so few pilgrims do), is compensated for with rich reflections on everything from the gospels to Aby Warburg to meteorology. In his attempt to re-mythologize lightning, Kosky fruitfully infers that modern critics may need to draw upon religious vocabulary, which could have the effect of prolonging encounters with the many works of art he explores.

Kosky agrees with some celebrants of rationalism that one can pursue “fully-secular and deliberate strategies for re-enchantment.” But he also pushes against the inference that religion is necessarily naïve, irrational or hypocritical. At the same time, he hopes to summon a sense of wonder without a particular debt “to this or that religious tradition, symbol, or concept.” As a result, he deliberately distances himself from Dan Siedell’s God in the Gallery, a book happily committed to the Nicene Creed. Still, the most fruitful texts that Kosky mines emerge precisely from the specifically Nicene context he eschews, and it is questionable whether such fauna can survive outside their native ecosystem. In short, Kosky wants to have his religious cake and eat (or at least nibble) it too.

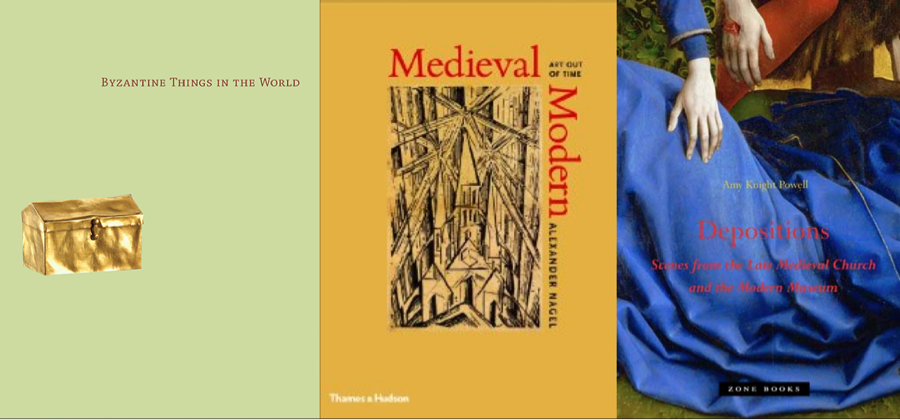

Kosky is not alone. A series of recent books, sensing the impoverishment of modernity, have attempted to put contemporary art into conversation with resources from the classical Christian era, whether verbal or visual. These frequently ingenious publications each make considerable improvements on now tired secular truncations. Byzantine Things in the World is the record of a show that made gorgeous contrasts between the Byzantine and modern holdings of the Menil collection. Infusing Byzantine theological formulae with animistic insights, the catalogue assumes “we live in rationalist times, and we no longer believe in the advent of spirit into our world,” even while it gently bids us to “think ourselves into a universe where the realm of the spirit [is] not so far away.” Likewise, Alexander Nagel’s Medieval/Modern attempts to break down modernist chronologies, revealing structural similarities between medieval and modern works of art, even exposing modernism’s parasitic relation to the medieval. Amy Knight Powell’s Depositions does something similar, violating the art historical obsession with contextual retellings by “promiscuously associating . . . objects of different times and places,” namely late medieval altarpieces and contemporary art installations. But like Kosky, none of these publications, or parallel conferences, seem completely comfortable with the ontological claims of ancient Christian vocabulary. Modern art, in its pairing with the medieval or Byzantine, always seems, so to speak, on top.

Even while modern chronologies are challenged, the underlying metaphysics assumed by such accounts still feel, to me, lingeringly modern. Which is to say that, like Kosky, such publications, brilliant as they frequently tend to be, borrow materials from previously constructed religious bridges, but do so (in my reading, at least) to modify the same wobbling, secular frame.

All of this has caused me to look freshly upon Cecelia González-Andrieu’s Bridge to Wonder, for she does nothing of the kind. Hers is indeed a distinctly Catholic construction, both in her appeal to papal authority and to the contextual reality of her Hispanic Catholic community. Even if she would have done better to appeal to Jacques Maritain (as I suggested in my original review, and which I continue to believe), her nod to John Dewey seems to me now less a compromise than an attempt to meet the secular mindset where it is, a casual suggestion that might draw people otherwise less interested into the orbit of her project. González-Andrieu dares to break the bogus neutrality pact of secular art writing. “It appears that it is only through denying beauty, nature, and God’s immanence in the created order,” she asserts, “that an atheist position can be staked out in art.” Nicene and Chalcedonian Christianity is commendable, she infers, precisely becauseit offer mystery within clarity—two dimensions of theological discourse that Kosky seems to assume must remain separate.

All of this has caused me to look freshly upon Cecelia González-Andrieu’s Bridge to Wonder, for she does nothing of the kind. Hers is indeed a distinctly Catholic construction, both in her appeal to papal authority and to the contextual reality of her Hispanic Catholic community. Even if she would have done better to appeal to Jacques Maritain (as I suggested in my original review, and which I continue to believe), her nod to John Dewey seems to me now less a compromise than an attempt to meet the secular mindset where it is, a casual suggestion that might draw people otherwise less interested into the orbit of her project. González-Andrieu dares to break the bogus neutrality pact of secular art writing. “It appears that it is only through denying beauty, nature, and God’s immanence in the created order,” she asserts, “that an atheist position can be staked out in art.” Nicene and Chalcedonian Christianity is commendable, she infers, precisely becauseit offer mystery within clarity—two dimensions of theological discourse that Kosky seems to assume must remain separate.

When originally reading González-Andrieu’s book, I was puzzled by her chapters that evoked the work of her students, a move which seemed to me—then fresh out of graduate school—unprofessional. But now, having taught for three years, I see what she means. Religious communities such as the Christian college where I teach, offer sanction for the creation of religiously-informed art that regnant critics, due to a frankly confessed prejudice, aver. Micro-art worlds can be stultifying, but they are also frequently more interesting than the predictable McArtworld beyond.

A further cause for reconsideration of Bridge to Wonder was witnessing Cecelia González-Andrieu in person. Saddled with a terrible cold, she nevertheless made the venture to be the keynote speaker at the Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA) conference hosted by my home institution, and gave a spirited address that energized the entire gathering. Sergio Gomez, one of the artists discussed in Bridge to Wonder, accompanied her and gave a similarly evocative presentation of his work. Over and over in Bridge to Wonder González-Andrieu appeals not just to her own insights but to the value of her community, but—in my case—this had to be seen to be believed. As she says in a different context,

A further cause for reconsideration of Bridge to Wonder was witnessing Cecelia González-Andrieu in person. Saddled with a terrible cold, she nevertheless made the venture to be the keynote speaker at the Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA) conference hosted by my home institution, and gave a spirited address that energized the entire gathering. Sergio Gomez, one of the artists discussed in Bridge to Wonder, accompanied her and gave a similarly evocative presentation of his work. Over and over in Bridge to Wonder González-Andrieu appeals not just to her own insights but to the value of her community, but—in my case—this had to be seen to be believed. As she says in a different context,

I am a Latina theologian, and for me the work of theology must always be done “close to home,” as you say. If I am going to be of some service to Christian communities (whether they are artists, or farm workers, or both) I need to speak with these communities, not about them.

Again, it is that very refusal to speak about religion but from within it that sets González-Andrieu apart from the books surveyed above. While previous generations might have dismissed this posture as sub-academic or narrowly confessional, such an assumption can no longer be taken for granted. As the German physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker put it: “In our time a critical examination of secularization is beginning at exactly the same time as secularization is achieving a consistency hitherto unknown.” The formidable tomes questioning the hegemony of an ostensibly “neutral” secularism have been written. Secularism, it is now becoming clear, is already a commitment, even a religious commitment of sorts (and a rather peculiar one at that), which is vulnerable to the same historical scrutiny to which religion has long been subjected.

There is, furthermore, no guarantee that the secular confession gets first dibs at the creationof contemporary artists, as if such artists were somehow automatically on the secular “team.” Jacques Barzun’s diagnosis from decades ago still stands.

There is, furthermore, no guarantee that the secular confession gets first dibs at the creationof contemporary artists, as if such artists were somehow automatically on the secular “team.” Jacques Barzun’s diagnosis from decades ago still stands.

Art [is unable] to reach the divine center from which redemption comes, and is punished for its presumption… Art cannot be ‘a way of life’ because . . . it lacks a theology or even a popular mythology of its own; it has no bible, no ritual, and no sanctions for behavior. We are called to enjoy but we are not enjoined.

As a fish requires water, art’s proven incapacity to enjoin necessitates that it borrow some kind of metaphysics in order to survive. While the aforementioned spate of recent publications reveals a widespread dissatisfaction with the secular milieu, piecemeal supplementation may not suffice. In other words, the bridge to wonder on offer by secularism, even when borrowing heavily from religious discourse, remains a rickety thing.

All of which leads back to the issue of lightning. What my upbringing in suburban New Jersey failed to impart is that lightning never needed the “re-enchantment” for which Kosky and others long. This is because its traditional religious interpretation never disappeared as much as it was forgotten, and only a Hegelian hangover of presumed secular inevitability keeps one from seeing otherwise. Which is to say, Franklin and Whitman are not the only alternatives, even if they remain the primary public options the amnesiac Delaware Valley currently present to its inhabitants.

The secular spell on lightning can be broken in a variety of ways. I recall one evening, at the midnight liturgy at St. John the Forerunner monastery in northern Greece, witnessing lightning in an Orthodox Christian milieu. Within the ancient Byzantine church, the only light to reach the numerous icons came from flickering candles reverently lit by nuns whose black habits merged with the darkness. But when, that same night, a thunderstorm rolled through the mountains, ensconcing the chapel that was pulsating with worship, lightning suddenly flooded the sanctuary with momentary brilliance as if it was the second coming itself. “The Son of Man will be in his day like Lightning” (Luke 17:24). And then the darkness, now paradoxically more luminous, returned.

The secular spell on lightning can be broken in a variety of ways. I recall one evening, at the midnight liturgy at St. John the Forerunner monastery in northern Greece, witnessing lightning in an Orthodox Christian milieu. Within the ancient Byzantine church, the only light to reach the numerous icons came from flickering candles reverently lit by nuns whose black habits merged with the darkness. But when, that same night, a thunderstorm rolled through the mountains, ensconcing the chapel that was pulsating with worship, lightning suddenly flooded the sanctuary with momentary brilliance as if it was the second coming itself. “The Son of Man will be in his day like Lightning” (Luke 17:24). And then the darkness, now paradoxically more luminous, returned.

Had my Emerson-obsessed pubic school education taught me to look beyond the limitations of Franklin and Whitman, there would have been no need for travel to Greece. As with most high school students, I was inoculated against Jonathans Edwards with a mandatory reading of one of his worst sermons. Little did I know, however, that he had broken out of the confines of a narrow Calvinism in order to reconceive all natural phenomena anew. As Perry Miller put it:

Nature . . . was [for Edwards] not a disjointed series of phenomena; it was a living system of concepts, it was a complete, intelligible whole . . . Nature had become as compelling a way of God’s speaking as Scripture . . .

Which is to say, resisting a nascent modernity, Edwards dared to perceive “nature” as cosmos. And yes, of course, lightning is included. “The extreme fierceness and extraordinary power of the heat of lightning,” he wrote in Images and Shadows of Divine Things, “is an intimation of the exceeding power and terribleness of the wrath of God.” Edwards’s insight elucidates an aspect of God that the secular world, to its considerable impoverishment, first caricatured and then expunged. But Edwards’s perspective on lightning is more than outdated old time religion—instead, it fuses the sublime and the beautiful, aspects of glory that the modern epoch saw fit to divorce.

Like another great Protestant project of speculative theology, that of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Opus Maximum, Edwards’s typological system was never completed. And that may be for the best. As Perry Miller understood, there remains “a close connection between typology and Christian art,” making typology an invitation to artists, not just theologians, to participate in the same cosmology. Indeed, as I have pointed out in a different context, it is no coincidence that one of the most enduring essays of modern art criticism begins with a fragment from the same Perry Miller’s reflections on Edwards. Whether through Michael Fried in the 1960s or in more recent reflections today, secular criticism has long seen the need to supplement its own tattering bridge to wonder. And if one crumb from the religious table can go that far, why not then actually sit down to enjoy this open feast?

Perhaps resistance to such an invitation comes from religion’s countless injustices and its seemingly ineludible intolerance. When a Catholic library burned down during his lifetime, Jonathan Edwards called it a fulfillment of prophecy: the drying up of the rivers of Babylon. Even the Anglican tradition that I myself profess was condemnable to him. Shouldn’t such a frank assessment of Edwards be enough to undermine his credibility, as well as my attempt here to put him in touch with González-Andrieu’s Catholic project? Not necessarily. As George Marsden put it, we must sort out “the lasting insights of a great mind of the past from the non-essential assumptions of another era with which those perennial truths may be intertwined.”

Perhaps resistance to such an invitation comes from religion’s countless injustices and its seemingly ineludible intolerance. When a Catholic library burned down during his lifetime, Jonathan Edwards called it a fulfillment of prophecy: the drying up of the rivers of Babylon. Even the Anglican tradition that I myself profess was condemnable to him. Shouldn’t such a frank assessment of Edwards be enough to undermine his credibility, as well as my attempt here to put him in touch with González-Andrieu’s Catholic project? Not necessarily. As George Marsden put it, we must sort out “the lasting insights of a great mind of the past from the non-essential assumptions of another era with which those perennial truths may be intertwined.”

Edwards’s anti-Catholicism was regrettable, and perhaps contextually inevitable. But what unites his evangelical perspective, the tradition in which I teach at Wheaton College, and the richly Catholic perspective of González-Andrieu, is the very Nicene commitment that Kosky demurs. Part of the reason González-Andrieu can celebrate the connections between, as she puts it, “an Anglo American Protestant and a Roman Catholic Latina” is because both traditions are part of the same Nicene bridge. And impolitic as it may be to say so within earshot of most contemporary art critics, the reason this particular bridge to wonder endures is because it was not built by humans, but by the Nicene Creed’s fully human God.

The secular confessional commitment that rules out religious claims has dominated the discourse of art history and criticism to the point that even the publications that attempt to break its hold still find themselves residually constricted. But while this approach has been overwhelmingly prominent, it is still just one approach, no less tenable than religious perspectives. Yes, all human creative enterprises worth pursuing begin with Plato’s wonder (thaumazein),but genuine wonder is never stationary, let alone an end in itself. Human wonder is dialogue, not monologue. The divine response has been given, and it is an answer that evokes even more wonder than the original question itself. Cecelia González-Andrieu manages to inhabit such wonder, winsomely, from her place as a Catholic theologian. The question for me is whether similar commitments can be tolerated in the realm of professional art writing without being struck dead by a fiery bolt of peer review. Such commitments, I confess, sometimes feel to me as likely to be sanctioned by art history and criticism as the Delaware River is likely to one day be surmounted by a Jonathan Edwards bridge.

8.31.14 | Anne Michelle Carpenter

Response

Among the long, black rafters

Introduction

“I stood on the bridge at midnight,” writes Longfellow, “as the clocks were striking the hour.” As the poem continues, he expands his theme of the moonlit bridge and the complex shadows it casts over the water:

Among the long, black rafters

…..The wavering shadows lay,

And the current that came from the ocean

…..Seemed to lift and bear them away

He remembers the sorrows of his “hot and restless” heart long ago, carried away by the years. He imagines others with burning hearts also coming to the bridge in order to un-burden themselves alongside the waters.

And forever and forever,

…..As long as the river flows,

As long as the heart has passions,

…..As long as life has woes;

The moon and its broken reflection

…..And its shadows shall appear,

As the symbol of love in heaven,

…..And its wavering image here.

Cecilia González-Andrieu’s Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty is an effort to draw out the earthly “symbol of love in heaven” as it is expressed in art, especially the visual arts. With due respect to Longfellow, González-Andrieu’s grasp of heaven’s ability to be symbolized on earth is stronger and richer. Rather than “wavering,” divine love expresses itself powerfully through beauty, and indeed, through human works of art. “These works,” she writes, “are a way to know one another through our questions and our experiences as we search and sometimes indeed beautifully find the shimmering glow of the presence of God.”

The figure of a bridge dominates the book with deliberate insistency, ever there to remind the reader that the bridge that Bridge to Wonder attempts to articulate has not always been lauded or perceived by either the art world or the theological one. I took personal delight in the idea that the Golden Gate Bridge is the structure that González-Andrieu has in mind as she works, a bridge that I am coming to know well since moving to the Bay Area of California to teach. The very specificity of the image is significant; just as the Golden Gate Bridge is not any old bridge, González-Andrieu imagines a concrete and generous relationship between art and religion, and not a vague or notional peace accord. In support of this creative relationship of wonder between art and religion, and in support of the book, I would like to forward three interconnected themes that are fundamental to the efforts of Bridge to Wonder, themes deserving of concerted attention that will, I hope, genuinely illuminate the path González-Andrieu has set out to follow. These three themes are (1) overcoming dichotomies, (2) art and religion as experiences of wonder, and (3) wonder as experienced in a tradition. I will highlight important aspects of each theme in order to ask further questions about them and their relation to one another.

1. Overcoming Dichotomies

One of the significant over-arching ideas in Bridge to Wonder involves theological aesthetics as an avenue beyond typical oppositions presented in certain modes of Western thought. Of particular concern here is the old dualism between spirit and matter, which González-Andrieu wishes to overcome by considering the power of “revelatory symbols,” a consciously broad phrase, to unite spirit and matter.

González-Andrieu’s efforts here, consistent throughout the book, are helpful especially when they do not cease their concreteness. While it can be hard to imagine a “revelatory symbol” or a “false dichotomy” from a blank page, the author supplies us with considerable numbers of examples that highlight her meaning. Of particular importance for the book are the examples of two opposed art shows given at the same time with radically different meanings and receptions, Seeing Salvation and Apocalypse, as well as the example of the controversy over the Christ d’Assy. In each case, symbols as revelatory and symbols as dictating a false dichotomy receive careful attention. González-Andrieu also draws considerably from her own experiences of faith and beauty, both as a child and as an adult. This adds not simply personal warmth to the book, but also deepens its express conviction that the wonder of beauty can leave no one unchanged.

These efforts to overcome strained dichotomies remind me very much of Hans Urs von Balthasar’s references to beauty as in some special way the guardian of the “wholeness” of being. In Balthasar’s parlance, we encounter the “form” of beauty in every experience of beauty, a form that is at once specific and transcendent, at once a particular experience and a call to the whole of existence. “The appearance of the form,” he writes in his introduction to Glory of the Lord, “as revelation of the depths, is an indissoluble union of two things. It is the real presence of the depths, of the whole reality, and it is a real pointing beyond itself to these depths.”

Beauty, then, in its accessible inaccessibility through a work of art, can make us aware of this profound complexity [of the mystery of God]—not only by the symbolic representation of the beautiful, but by prompting the movement of our heart in the quest of unattainable Beauty.

2. Art and Religion as Experiences of Wonder

In view of the whole to which beauty testifies, González-Andrieu moves to consider the depths of our religious experiences as well as the depths of our experiences of art, all in order to show that both are in many ways oriented to one another. “Here art shows its ability to speak where words cannot,” she explains, making it fundamental to the task of theology, which is always wrestling to express the inexpressible.

For one, it is clear that art and religion (or theology) remain distinctive. I am not against such a position, but I am interested in how this authentic dichotomy functions for González-Andrieu, and what it means for her.

3. Wonder as Experienced in a Tradition

My rather broad question above may be helped by a fascinating study González-Andrieu makes of the Church at Assy, which had been populated with modern art from contemporary artists of the time. A special point of focus is the crucifix, Christ d’Assy. Of the works in general, González-Andrieu comments, “Theology was absent from the church at Assy because the project was about art as art, and about superimposing this idea on a two thousand year old tradition that understood art as a mirror of ‘the infinite, the divine.’”

Of Christ d’Assy, González-Andrieu, explains that, rather than speaking in the complex “voice” of which art is capable, the work utters a simple “No” or negation to the Incarnation. It articulates the atheism of its artist. “As a source of theology, Christ d’Assy denies the Incarnation through dissolving the body of Christ; neither cross nor man is ultimately present; all that is left is a cipher.”

In this conversation, I want to highlight the importance of the Incarnation in guiding González-Andrieu’s critiques. I am curious how far this sort of logic instructs the building of her bridge, and I am eager that she be more explicit with us so that we might be students of such logic. I am as well interested in how it is possible at all to become a student of wonder, or perhaps more strongly someone who is asombrado. She mentions an instinct that the community has against Christ d’Assy as the authentic instinct of faith. How are we able—if we are able—to encourage this interpretive involvement in wonder on the part of the faithful interacting with the symbolic world of, say, a church, or the natural world? Or, inversely, how are we able—if we are able—to encourage similar investment in Christ and tradition among artists, so that they might in their own ways speak more than a “No” to faith? I am curious if tradition or traditions form a connecting sinew in a conversation such as this.

I am curious as well over why Christ d’Assy continues to be disallowed in a church. It is “a powerful and legitimate examination of radical doubt, but it did not belong in a church.”

Conclusion

I enjoyed reading Bridge to Wonder, as it provoked in my mind many interesting further questions and taught me a great deal about specific forms of art, controversies in art, and responses to art. In a work shaped by two complex disciplines, art and theology, the book nevertheless maintains its sense of its own argument throughout, no easy achievement to say the least. As I have read about the “bridge,” I am in an odd way curious over what continues to be separate, what needs a bridge at all. If art and religion are still too broad for such a consideration, there is yet faith and its relationship to doubt, as expressed in art. It is my genuine hope that I have in some small way led us back to this fundamental question over what is bridged yet separate, which in many ways underlies the book.

As a final note, I want to thank Cecilia González-Andrieu for her book, and for the opportunity to take part in a conversation about it in a public, scholarly forum. I look forward to see how this conversation continues to take shape among its resident scholars.

“The Bridge by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: The Poetry Foundation,” accessed June 1, 2014, http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.poetryfoundation.org/poem/180811.↩

Cecilia González-Andrieu, Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012), 6.↩

Ibid., 18.↩

Ibid., 19.↩

Ibid., 36.↩

Jean-Louis Chretien, The Unforgettable and the Unhoped For, translated by Jeffrey Bloechl, 2nd ed. (Fordham University Press, 2002), 99. “The excess of the event over the look of expectation can show simply the finitude and fallibility of human understanding. But it can also be understood positively as the mark of an origin that is more than human.”↩

González-Andrieu, Bridge to Wonder, 39.↩

Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, translated by Joseph Fessio and John Kenneth Riches (New York: Crossroad Publications, 1983), 118.↩

Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, 19.↩

González-Andrieu, Bridge to Wonder, 58.↩

Ibid., 59.↩

Ibid., 67.↩

Note the continued separation or distinction between the two, as in this excerpt: “I propose that to understand and articulate how the arts work religiously and how the religious works aesthetically is a special kind of engagement in itself, constituted as it is in the how of interlacing the arts and the religious and the what of the uniqueness, integrity, differences, and questions of each, as these are seen in relation to each other” (87). See also the discussion on page 64ff.↩

Ibid., 143.↩

Ibid., 74.↩

Ibid., 145.↩

Ibid., 147.↩

Ibid., 146.↩

12.25.14 | Cecilia Gonzalez-Andrieu

Reply

Response to Anne M. Carpenter

Before his all too early passing in 2010, my beloved mentor, Alex García-Rivera (one of the pioneers in the field of Theological Aesthetics), reminded me that writing about Beauty needed to itself be beautiful. In this way, I think García-Rivera underscored his important category of “living theology.”

Anne M. Carpenter’s evocative title, “Among the long, black rafters,” and her choice of beginning her thoughtful essay with poetry places her readers on a particular moonlit bridge and tells me that she and I understand each other. The beauty of her language, as well as her use of embodied concepts such as “personal delight,” transparently communicate that her question about “how to become . . . someone who is asombrado?” could very well be answered through her own experiences.