Crossing the Rubicon

By

10.22.18 |

Symposium Introduction

One wonderful thing about philosophical modernity—the kind that begins roughly with Descartes and comes to something like an end in the twentieth century—is that one knew where one stood. Science was believed (and still is by many) to be the one source of true knowledge. Everything else had to bow before it in one way or another. We only need to remember the huge dominance (at least in English-speaking countries) of logical positivism. As long as logical positivism ruled philosophy, philosophy of religion was suspect. Indeed, even ethical judgments were put into question by the position known as “ethical emotivism,” which held that all ethical statements were not even worthy of the designation “statement” and instead were simply expressions of one’s emotions. For logical positivists, only statements that are tautologically true or empirically verifiable have the right to be called “statements.”

Yet people finally realized that this statement couldn’t pass its own test. The idea that something was only true tautologically or empirically was itself neither true by tautology nor by empirical verification. As a result, logical positivism was discredited. The idea that scientific knowledge is the only true knowledge is much less prevalent today, though it is still the default mode of many people. But the loss of the privilege of science over everything else made many things possible. For instance, it is no coincidence that the Society of Christian Philosophers (largely an analytic organization with about 1,000 members) was founded in 1978, at the time logical positivism was dying out. As philosophers returned to a more pre-modern way of thinking, studying medieval philosophy suddenly got much more interesting. However, many thinkers have decried the loss of the modern consensus for the “postmodern” ways of thinking that were made possible (if you don’t like the word “postmodern,” then feel free to choose your own word). This also comes as no surprise. As I said earlier, at least you knew where you stood during modernity.

Perhaps this is too strong a statement, but I think Emmanuel Falque’s book Crossing the Rubicon couldn’t have been written in the age of modernity. Indeed, while many have found the “return of religion” or the “theological turn in phenomenology” to be a surprise, my reaction is: mais oui, bien sûr! Having been dismissed for so long as simply superstition, suddenly thinking as a religious believer became possible—in some cases, even respectable. Alvin Plantinga has long said that starting with the belief that there is no God is in no way more neutral than starting with the belief that there is a God. The point here is not that you can simply start with any beliefs you like but that there is no neutral starting point. Philosophy, theology, and the branches of science have never been neutral. Further, everything (as Derrida reminds us) has its own set of beliefs. Some of these can be proven but others of them are simply “prejudices” (or what the philosopher R. G. Collingwood termed “absolute presuppositions,” by which he meant the building blocks of thought or things that pretty much everyone takes to be true). Of course, Gadamer, who almost singlehandedly rehabilitated the idea of “prejudice” hardly thinks that anyone is simply entitled to their prejudices without questioning them, but his point is that there is no way of simply getting rid of them (which was the opposite of one of the main points of logical positivism—that you could get rid of them).

More fundamentally, Falque thinks that philosophy and theology, while different, are complementary. Which means the Rubicon can be crossed, or the distance between the Institut Catholique de Paris and the Sorbonne is not quite so wide after all. “Theologians make a point of reminding philosophers that they incessantly surpass the boundaries set by reason,” says Falque. While he does not put it this way, we might say that many things we believe to be “common sense” or obviously correct are things we really don’t much understand. We have been speaking of “matter” for centuries, but what exactly is it? Is there really such a thing as a “force” of gravity or a “law” of physics or is this simply our way of talking about the world? Even though theology and philosophy differ in terms of such things as how they proceed and the methods used, they are not really separable in any strong sense. As Falque puts it, “those who believe that they should still engage in the battle between philosophy and theology should now see that this clash would forever be sterile” (132). Philosophy helps us to understand theology: one need only think of how the formulation of the Trinity is founded upon Greek concepts. The task for theologians, according to Falque, is that they find new ways of formulating theological beliefs that speak to contemporaries.

10.30.18 |

Response

In the Way of Communion

A Reply to Emmanuel Falque's Crossing the Rubicon

Emmanuel Falque’s work calls into question a truism that still governs most European and American philosophy today. Contrary to what is commonly assumed, the philosopher can enter into theological territory without diminishing her specific dignity as a philosopher, and she will become a better philosopher for doing so. “The better one theologizes,” Falque claims, “the more one philosophizes” (107), and conversely, “the more we theologize, the better we philosophize” (25, 147). At a basic level, Crossing the Rubicon is a book about what philosophy is and can be. The strength and surprise of Falque’s argument, as I read it, consists in the way he grounds the crossing into theology in philosophy itself, as philosophy, while at the same time proposing that a specifically-Catholic and confessional approach makes this possible. Such a conjunction may seem counterintuitive at first glance. It is a powerful and compelling proposition, but everything comes down to understanding what it means.

Falque does not pretend to be the first contemporary phenomenologist to make an excursion into theologically territory, but he is unique in the way that he makes the foray explicit and systematic. The problem with other approaches, in his view, is that they tend to remain beholden to an imposed straightjacket: One is either in the realm of philosophy or theology and cannot have both at once. Falque candidly and without inhibition makes the “crossing” itself an unequivocal theme, where “philosophy and theology” ultimately belong together, even while they remain irreducible, distinct, and unconfused. The era of disjunction, as Falque sees it, is over. It is important to emphasize at the outset that Falque does not frame philosophy’s engagement with theology in terms of an appeal to another world or to an indeterminate transcendence, but in what he calls “the human” or “finitude.” As much as the philosophical, the theological, here, concerns first of all the human. The currents of the Rubicon do not run along the outer edge of finitude, but through the middle of it.

One thing I admire about Falque’s text is that it is not first and foremost about texts, but about life, and for those who know him, it is clear that Falque first lives what he writes. “Phenomenology,” perhaps more than “hermeneutics,” is the privileged dialogue partner for “philosophy and theology” in a Catholic mode. In other words, Falque shifts the hermeneutical ground from the text to a more original field of meaning. It is not a question of a communication of consciousness, as for Dilthey, or a fusion of historical horizons, as for Gadamer, but of the living body and the voice. It is already an achievement for Falque to locate the hermeneutical enterprise in a more fundamental field of experience. Ultimately, he is forging a hermeneutic of the Eucharistic body, and this part of his argument in itself deserves attention as a significant contribution to contemporary debate.

One may be tempted to ask: What is our experiential way of access to the meaning of the Eucharistic body and voice? How does this body give itself phenomenologically? Is it possible for the philosopher, as philosopher, to correctly interpret its voice without undergoing the sacramental initiation into the rite? If phenomenology is to retain its rights, it would seem that crossing the Rubicon into theology paradoxically also requires passage through the baptismal font, if something like an experience of the Eucharist is to be describable. Yet Falque rightly refuses any such “forced baptism” of philosophy (or the philosopher) and confirms, correctly in my view, that there is also room for the investigation of phenomena without the imposition of a confessional prerequisite. But can we know that the philosopher and the theologian are treating the same phenomena if the philosopher has not also passed through these waters? There are of course ways of treating the scriptural text, for example, in a non-confessional mode. But the Eucharist as it gives itself? I don’t want to raise this question rashly, so let us first follow Falque’s argument in order to pose it more precisely.

In fact, Falque upends completely how the movement toward confessional faith is construed today, in popular opinion as much as in philosophy. He insists on the universality and priority of an “always believing” condition, whatever the object of this belief may be. No one, neither the atheist nor the so-called believer, is ever in a situation of choosing between non-faith and faith. The world is not divided up, so to speak, between believers and unbelievers. Those are not the options, because believing is not optional at all. We are all believers, and irremediably so, because we are conditioned by a primordial belief in the world. Whether we call it a “world of silence,” obscurity, the “there is,” brute nature, or an anonymous and impersonal chaos, hardly matters. “A same world, always ‘pre-given’ precedes and founds all belief, whether philosophical or theological” (94).

This universal and originary belief in the world is the soil in which the specifically-confessional belief in God finds its ground. Falque is not arguing that a theological content is already present or implied by this philosophical belief in the world. The philosopher can remain “always believing” without making any theological commitment. Falque even goes quite far in arguing that the difference between “philosophical belief” or “perceptive faith,” on the one hand, and “confessional belief,” on the other, is not so much a difference in the subject matter or object of belief, but rather, in the ways or paths to be traveled.

If we then ask what confessing belief adds to universal philosophical belief, the answer is, strictly speaking, nothing. The confession of faith is not imposed or superimposed on philosophical belief, nor does it extend or complete it. Rather, the movement from universal, perceptual faith to a confessing faith is a movement of “kerygma and decision,” in which philosophical belief itself is transformed by the encounter with theology. The decision in question, the decision of confessing faith, is not a matter of an ontic choice of this or that, nor a matter of assuming responsibility for what one has chosen. It is a decision that operates at a more basic level, one might say, as “an ontological act of choice upstream of every choice,” and as a “discovery of oneself in one’s ipseity as a choosing being” (108). Grounded in the question of choosing, this is not a philosophy of religion in general, but a philosophy of religious experience. The experience of the confessing believer is not beside the point.

If philosophy can allow itself to be transformed by theology, such a transformation appears at first to be rooted in the simple requirement that I choose. And it is true: I must choose, and there is no choice. But my ambition to be the first to choose, Falque argues, always turns out to be mistaken. It is not within my capacity. A further meaning of the conjunction with theology is now clear, because the choice I face arises in response specifically to the kerygma, to the proclamation of the resurrection. I do not arrive at this discovery from a position of neutrality. The kerygmatic decision is not a possibility that can simply be read from the tea leaves of philosophy. It is born of an encounter under the shadow of theology. In the proclamation, I encounter the one who chooses me. In this encounter, the meaning of choosing itself is transformed, and I come to see that I am first chosen. “You have not chosen me, but I have chosen you” (John 15:16).

Falque gains much by this approach. He avoids what he considers to be the excessive privilege of passivity over activity, which he thinks is a consequence of the misguided effort to keep phenomenology pure at all costs, or to make revelation a moment of pure phenomenology. As a result, Falque can then also describe confessing faith as an active co-operation with God, rather than simply as a passive moment rooted in the nature of things or in the immanent telos of philosophy. That is how Falque avoids burdening philosophy itself with a content or finality that, strictly speaking at least, is not proper to it. In the conjunction with theology Falque envisions, philosophy’s own integrity is not compromised, but preserved and even secured.

We can now see more clearly how philosophy and theology finally relate in Falque’s schema. They are distinguished by their points of departure (the human as such, or God, respectively); their modes of proceeding (heuristic, or didactic); the status of the object analyzed (possible, or actual); and, finally their object. On this last point, the question of their subject matter, Falque says that philosophy and theology paradoxically “differ least.” Falque here argues that an object, “the same phenomenon,” can fall in distinct ways under the purview of different disciplines. “The force of theology as a discourse beginning with God does not hinder philosophy as a discourse on the God-phenomenon appearing to the human” (126).

But it is indeed possible, and I believe necessary, to ask whether philosophy and theology do in fact, at any point in their joint itineraries, share one and the same object. What Falque, not without reason, seems to take as foregone conclusion—“a community of the object,” shared by philosophy and theology—is for me the very thing that needs to be demonstrated, since it is always possible that the veneer of a common vocabulary masks differences that could well be incommensurable. If we ask how a community of the object might be achieved, it is clear it must be achieved in a way that is legitimate for philosophy and also for theology. I would thus like to ask a question Falque himself poses, although in a different sense than he means it: “Having become allies, have they actually met each other?” (140).

Falque wants to get beyond the point where the two remain only staring one at the other, without entering into any deeper engagement. But is it not also a question of how their objects can be determined to be in common, whether those objects be humanity, or life, or God (assuming “object” is the appropriate term here)? The stakes of finding a common terrain are high. Falque is completely right, in my view, that it is up to philosophy to liberate theology “as it makes it its own object,” heuristically, descriptively, and in the mode of possibility (151). I would add only that the community of object itself must also become manifest. And this question about the object, once posed, then also turns out to include also a question about its mode. How can we describe phenomenologically the revealed and what is “in-common” with it if the manner in which it is revealed is not actualized? For me, this is one of the great questions. For my part, I approach this by asking whether the “life” of phenomenology is the same as the “life” of theology. If it is, we should be able to show that it is. If it is not, we must also wonder, why not?

Falque takes belief in the world as what is most basic and universal, but this is not the shared object that matters most. Over the course of his argument, the common terrain shifts from the “world” as the universal object of belief, to the “human” or “finite” as the point of departure for philosophy. The “human” is philosophy’s proper object, and that which theology transforms. The phenomenological question, in my view, is: how does this sameness, and thus also this transformation or metamorphosis, appear from the inside, that is, for the one or the many who undergo it? In order for such a “community of the object” to become manifest, must phenomenology in some sense not still remain strictly phenomenology, as it enters into theology, in order for a community of object to become manifest precisely as common? If so, I am inclined to say that the conjunction of “phenomenology and theology” may require a somewhat stronger disjunction between them, so that they can be conjoined, so that their juncture is meaningful.

As a way of clarifying the angle from which I approach Falque’s argument, I believe it is also possible to ford the same river by following Augustine and Michel Henry in making not the world, but life, the basis of a common and universal belief. “Even if the mind doubts,” Augustine says, “it lives” (On the Trinity, X, 10, 14). “I was brought up to your light by the fact that I knew myself both to have a will and to be alive” (Confessions, VII, 3, 5). My own approach goes in this direction from the side of theology. Without being able to defend or develop the claim here, I am confident that such an approach will confirm, reinforce, and compliment the broad contours of Falque’s itinerary. One might say that grounding a common belief in life would then make way for a hermeneutic under both elements, that is, both of body and blood—if the “life of the flesh is in the blood” (Lev 17:11).

The work of the theologian, as theologian, cannot remain unaffected by Falque’s claims. For even while he works within the philosophical register, Falque poses a fundamental question to theology about its own mode of proceeding, and it deserves to be emphasized. The didactic or dogmatic way of proceeding becomes a weakness for theology, Falque says, if it is taken as dropping from above, rather than as rooted in a specifically human inquiry from below. “Must we not accept in theology too an order of discovery beginning with the human—from below—that does not surrender immediately to the imperative of the order of teaching beginning with God—from above?” (126). Anyone who teaches theology today confronts the weight of the question. It is beyond the scope of Falque’s book to answer it, and perhaps beyond his stated purview as a philosopher. As a theologian who is also a Catholic, I would argue that theology is not teachable unless it is first rooted in experience. Only by grounding the order of discovery in what manifests itself in experience will theology find a sure didactic path forward, “a common grammar with our contemporaries whose first language is the language of the human . . .” (133, cf. 151). That is now the task and the challenge. Falque has courageously taken the plunge. It is now up to theology to meet him midstream.

11.6.18 |

Response

The Geography of the Rubicon

Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies in the American Context

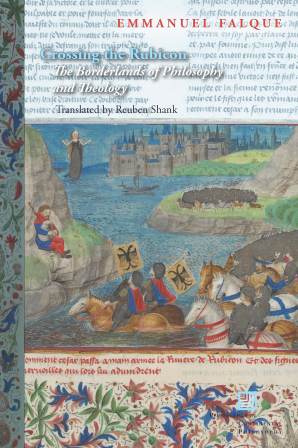

In his “discourse on method,” Crossing the Rubicon: The Borderlands of Philosophy and Theology,

Falque encapsulates his methodological discourse in the following mottos: “The better one theologizes, the more one philosophizes” (107), but also, “the more we theologize, the better we philosophize” (139). The benefits of crossing the disciplinary divide are, in other words, mutual. Falque observes that the benefit has thus far been felt mostly on the side of the theologians enjoying the “immense fecundity of phenomenology” while theology’s “counterblow” has not yet made its impact fully known to the phenomenological world (21)—an inequity Falque seeks to remedy, already implicitly in his previous works,

As the philosopher and the theologian cross in the Rubicon, they will have no choice in passing each other but to let themselves be transformed—each one by the other. The first will teach the second about the human journey. The second will make the first see that he cannot refuse to open himself—upon a decision, of course (Chapter 4, §14)—to the transcendence of the One who comes to “metamorphose” everything, to the extent to which he has first assumed it in its entirety. (151)

Crossing the Rubicon from philosophy to theology, or vice versa, brings the opportunity of growth in either direction.

Nonetheless, the possibility of mutual benefit requires that each remembers their citizenship in the land from which they travel; in other words, Falque is interested in encounter, not conversion. Indeed, this is one of the markers which, arguably, separates him from a previous generation of French phenomenologists who, by refusing the distance between the two disciplines and claiming certain topics (such as revelation, liturgy, Eucharist) as properly philosophical, also were less explicit about the confessional origin of those topics. Distinctly, Falque has no need to “baptize” philosophers like Badiou, Franck and Nancy, who might, nevertheless, make use of theology in interesting ways (138). Despite the fact that Falque employs a militaristic metaphor—Caesar’s crossing is a movement into battle—Falque’s model of the ensuing encounter, he insists, need not result in “crushing” one’s foe, but instead could be understood as an athletic contest in which one encounters an equal adversary against which to test, exercise, and thus, strengthen one’s own abilities (139).

Recalling that, in order to make this crossing productively and safely, one must remember and return to the land from which one travels, it is necessary to mark the distinct topography of each shore in order to be able to make that return. Falque argues that philosophy and theology are distinguished “not so much by their respective contents (after all, the Eucharist, the Passion, or the Resurrection can also be approached philosophically) than by their modes of proceeding—heuristic or didactic” and the direction of their approach, specifically whether the object of study is approached from on high or from below (24). Falque seeks a delicate balance between an over-unification of the disciplines which would confuse their methods and an over-separation which would, prejudicially, exclude legitimate objects of consideration to each. The balance is found thus:

Between philosophy and theology a difference must be maintained between (a) their ways, (b) their modes of proceeding, and (c) the status of the objects to be analyzed, while at the same time recognizing (d) the possible and paradoxical community of objects given to thought. (125)

In this schema, theology proceeds didactically—“what is said in opening must then also be repeated identically at the end”—with dogmatic force and “from above,” in order to treat an object it takes as (or claims to be) an actuality. On the other hand, philosophy proceeds heuristically; with an open and questioning spirit, it proceeds “from below” to consider possible objects (126). Regardless of discipline, however, Falque insists on the greatest overlap with respect to the object of study itself—whether considering prayer, liturgy, Eucharist, Incarnation, revelation, etc. In this way Falque characterizes theology as a “discourse beginning with God” whereas philosophy can be a “discourse on the God-phenomenon appearing to the human” (127). My question is whether this distinction makes as much sense in the American context.

Falque begins his book with a remark that the “relationship between philosophy and theology in France has recently shifted” (16). In France policies of laïcité, which forced theology out of the public university setting, are being challenged, and “locked doors have already given way” (16). What I wonder is if, in the American context, we might observe a self-imposed laïcité within, at least, academic theology. To explore this question, I will consider two centers of theological training in the United States, Harvard Divinity School and Chicago Divinity School. These institutions are interesting to consider not only because they are, arguably, amongst the most influential spheres in which training in theology occurs,

The divinity schools at Harvard and Chicago both offer a PhD degree, as well as MA and MDiv programs, the latter being the terminal degree for students seeking ordination or some other form of ecclesial ministry. This dual focus distinguishes these institutions from others, like Yale and Princeton, both of which institutionally separate theological training from the academic study of religion—institutionally they are geographically located in different schools or departments, with separate faculty teaching and advising the programs. At Chicago and Harvard, on the other hand, one can pursue a PhD in theology, or in anthropology of religions, religious ethics, Islamic studies, religions in America, history of Judaism, philosophy of religions, African religions, Buddhist studies, Greco-Roman religions, religion, gender and culture, and so on. (N.b. the plural, and implicitly comparative, form of many of those categories.) Furthermore, one can also pursue the terminal ordination degree, a masters of divinity. Both the academic and the ordination degrees are administered in the same buildings with the same faculty teaching and advising.

The study of theology in these institutions is less confessionally located and narrowly identified than the study of theology in either a Catholic seminary or Protestant seminary. A Catholic or Protestant seminary can both assume a uniformity of religious identity that is not possible in a more diverse or pluralistic setting such as Chicago or Harvard. Depending on the order of the Catholic seminary, philosophy may play a smaller or larger role in the curriculum; whereas in most Protestant seminaries philosophy will be emphasized less than cognate disciplines such as biblical studies in theological formation. A third possible setting in which we can consider the relationship between theology and philosophy would be larger Catholic universities such as Villanova, Fordham, Boston College, or Notre Dame, which have both strong theology and philosophy departments. These institutions are dually sympathetic towards the kind of relationship between disciplines that Falque advocates: on the one hand, these large Catholic universities historically have been more favorably disposed to the continental tradition within their philosophy departments,

Again, on this point, Chicago and Harvard, seem to occupy a unique and significantly different position as non-sectarian research institutions that continue to hold a place for the study of theology. Not without a shift, I would argue, however, from confessional theology to “academic theology”. This discipline of academic theology needs to be filled out further in order to see where it might fit within Falque’s schema of difference and beneficial encounter between theology and philosophy.

My Doktormutter, Sarah Coakley, would often voice a concern that the study of theology had become a study of “theologology”—that discourse on God had become, in other words, discourse on the discourse on God, a second-order study. If I understand Falque correctly, what Coakley meant by “theologology” is something akin to a process of “vulgarization” which is to be explicitly distinguished from the act of philosophical “thinking” (17)—the former being the mode of communicating clearly historical lines of influence and interpretive explanation. For better or worse, this portrait of pursuit of academic theology is correct. The primary audience of the academic theologian is the academy, and the academy is also the authoritative body determining what counts as evidence and legitimating the discourse as such. The academic theologian does not speak from, or to, a specific confessional location; while the identity of the academic theologian may be confessionally specific, it also may not. In either case, the academic theologian is trained not to fall back on that identity as a foundational authority for his or her argument. Rather arguments are defended and adjudicated based on grounds that are held in common with other disciplines: their reasonableness (understood in terms of internal coherence), as well as their ethical/pragmatic or historical grounds. Academic theologians have as their object of study discourse on God, understood as a human phenomenon and always necessarily placed within its historical context.

In other words, the study of academic theology, at least as it is found in the two major centers of theological study in the United States, proceeds very much “from below,” rather than dogmatically from above. To place it back in Falque’s helpful schema of the three different modes of faith—philosophical perceptive faith, anthropological religious faith, and theological confessing faith—one must conclude that academic theology in the United States can be said to assume, at most, the middle mode of faith which “indicates a possible relation to transcendence, whether or not it is named” (90). If academic theology is dealing in actuality rather than possibility, as Falque determines, than it is merely the actuality of “theologology”—that is the intellectual history of Christian thinking on God, the rich traditions of faith, doctrine, and practice that Christians have diversely produced through the history of Christianity. Put this way, it is difficult to clearly distinguish between the academic theologian and the philosopher of religion. In order to understand this shift in the conceptualization and production of academic theology, it is necessary to discuss its status vis-à-vis the shifts in the study of religion in the United States more generally.

Religious studies, which historically was born out of departments of theology, has for the most part banished its parent: theology has been pushed out of most departments of religion. Up until fairly recently philosophy of religion still held a prominent place within religious studies. However, with the material turn to “lived religion” in the 1990s, and the concurrent radical and thorough historicization of the field which problematized any natural, universal, or ahistoric notion of religion, philosophy of religion also increasingly came under suspicion as a subfield which was seen to be sneaking theology in by the back door.

Lewis defines religious studies as “the disciplined examination of religion, including religious thought, people, movements, practices, materials, etc., as well as reflection on the conceptions of each of these terms, without presupposing the validity of or privileging the study of any particular religion or group of religious phenomena”—neither presupposing the truth nor the falsity of any particular religion (7). In other words, religious studies cultivate a self-conscious discipline of openness. Where does theology fit into this discipline? According to Lewis, theology is too diverse a field to state whether or not it can be fit as a subfield within religious studies. Some theology “excludes itself by making conversation-stopping appeals to authorities conceived as unquestionable” (7–8), whereas the theology which does not, which continues to proceed “from below” clearly belongs within the academy. Note that for Lewis normativity is not the issue; theology and religious studies can and should make normative claims (just as political science, history and literature, let alone philosophy do). What is the crucial marker for entry into the academy is “a principled willingness to submit all claims to scrutiny and questioning, to insist that no assumptions, doctrines, or authorities are beyond questioning” (8)—to proceed “from below,” heuristically rather than dogmatically. Philosophy of religion, as well as any theology “academic” enough to follow these ground rules, can provide conceptual depth and synthetic ability to the study of religion. Thus, according to Lewis, philosophy is necessary to the study of religion, while a non-dogmatic theology is permitted as a subfield. The divinity schools of Chicago and Harvard retain a far more robust and central role for the study of theology within religious studies more broadly, but the non-dogmatic restraints are implicitly shared.

One appraisal of academic theology in the United States might be that it is has given up its own authority to speak otherwise than according to the standards of the secular academy. This negative evaluation may be correct, but it is not the only way to understand the position of theology within the secular university. It is also possible to understand academic theology’s insistence that it too proceeds from below and without the authority of speaking from on high, as itself a theological claim: its own acceptance of the inescapability of finitude, and the appropriate humility in recognition of that. Academic theologians might explicitly identify themselves as Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox, Methodist, Mormon or Anglican, or as non-Christian believers (as Falque reminds us we always believe in something [78]), but they cannot rely on that identity as providing access to a particular type of authoritative evidence for the argument they put forth. In this context it has become more and more difficult to adequately distinguish between the philosopher of religion and the academic theologian. This is precisely what Falque has argued can and ought to be kept clearly discrete in the French academic context in which the Sorbonne and L’institut catholique are both distinct and yet bridged by the Jardin du Luxembourg. The question remains whether, given the diminishing of the methodological distance between philosophy and theology, we can talk in the same way of crossing this Rubicon in the American context.

Emmanuel Falque, Crossing the Rubicon: The Borderlands of Philosophy and Theology, trans. Reuben Shank (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016). Subsequent references will be made parenthetically within the text.↩

See Le Passeur de Gethsémani, Angoisse, souffrance et mort. Lecture existentielle et phénoménologique (Paris: Cerf, 1999); Métamorphose de la finitude. Essai philosophique sur la naissance et la résurrection (Paris: Cerf, 2004); Les noces de l’Agneau. Essai philosophique sur la corps et l’eucharistie (Paris: Cerf, 2011).↩

As judged by placement rates of their graduates into academic positions and publications emanating from the two schools.↩

The University of Notre Dame is the exception here; however, one might argue that in its marriage of analytic philosophy and theology in the formation of “analytic theology” it follows the same pattern as Falque advocates.↩

This Catholic exception to the rule in the American theological scene raises the question of whether there is something uniquely Catholic in Falque’s vision which does not translate as well into other religious contexts.↩

For a recent expression of this suspicion, see Timothy David Knepper, The Ends of Philosophy of Religion: Terminus and Telos (New York: Palgrave, 2013).↩

See Thomas A. Lewis, Why Philosophy Matters for the Study of Religion—and Vice Versa (Oxford University Press, 2016); Kevin Schilbrack, Philosophy and the Study of Religions: A Manifesto (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014); Tyler Roberts, Encountering Religion: Responsibility and Criticism After Secularism (Columbia University Press, 2013).↩

11.13.18 |

Response

Crossing the Rubicon

Foreign Exchange or Hostile Incursion?

Introductory Thanks

My thanks to Bruce Ellis Benson, B. Keith Putt, and the Society for Continental Philosophy and Theology (SCPT) for the invitation to speak on this panel session at the 56th Annual SPEP Conference. My thanks, especially, to Emmanuel Falque for his friendship and mentorship, and for his work that brings us together today. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to both Tamsin Jones and Karl Hefty for their contributions and discussions during this session. It is an honor and a pleasure for me to be with you as a part of this panel today.

Before delving into my assessment of Emmanuel Falque’s project and its implications for the relationship between philosophy and theology, I wish to make a few preliminary observations with respect to Falque’s perspective and overall project goals. I shall then proceed to offer a brief exposition on his new paradigm for philosophical-theological interaction, and subsequently I propose a central benefit that his project affords in facilitating dialogue across differences (or even dissent). I then conclude by opening with a question, namely: does Falque’s account blithely ignore an essential—perhaps necessary and productive—hostility between philosophy and theology?

I. A Preliminary Observation: An Apologetical Justification?

On my reading, Crossing the Rubicon: The Borderlands of Philosophy and Theology is not, despite its title, primarily about the relationship between these two disciplines. Certainly this relationship is a central theme, the argumentation for which merits the consideration and debate of this panel today, but I nonetheless contend that in this text, the philosophical-theological relationship is a secondary or even incidental consideration to Falque’s more primary apologetical attempt at justifying his larger project.

While Crossing the Rubicon certainly does reframe the relationship between philosophy and theology (or, perhaps better, phenomenology and theology), Falque does so in the service of his larger project and, consequently, we cannot understand his “paradigm shift” for philosophy vis-à-vis theology independent of his more primary, overriding philosophical endeavors and concerns. Thus I must begin by noting that this text is not so pure a treatise on the relationship of these two disciplines but rather an apologetical justification of his own philosophical perspective over and above the thought of other French phenomenologists (surtout his mentor and philosophical sparring partner in a self-proclaimed “combat amoreux,” Jean-Luc Marion).

Anyone familiar with Emmanuel Falque’s writings will recognize two common themes that permeate the majority his works and which, I believe, characterize his contributions to phenomenology: (1) the reclamation of the primacy of the incarnate body, even in its finitude and limitations, and (2) a phenomenological perspective that takes immanence, rather than transcendence, as its point of departure. These two common themes emerge as central claims advocated repeatedly by Falque throughout his Triduum Philosophique, his habilitation in Dieu, la Chair, et l’Autre, and they unsurprisingly figure prominently throughout Crossing the Rubicon. (Incidentally, they also represent a stark difference and marked departure from the transcendental phenomenology of givenness, characteristic of Jean-Luc Marion.) Thus, if we are to understand and to appreciate Falque’s claims regarding the relationship between theology and philosophy in this text, we must first acknowledge these two commitments in his overarching philosophical oeuvre.

Falque goes to great lengths in Crossing the Rubicon to defend and to distinguish his “immanent” phenomenology from his philosophical forebears, and he uses such an unabashed traversing of boundaries as yet another aspect to distinguish his phenomenology from his predecessors who failed to make the journey—or, at the very least, those who failed to acknowledge that they made the journey:

“Crossing the Rubicon” is therefore not a reaction in relation to an assigned problem in some set of subject matters—namely, philosophy and theology—and to the mode of being of their approaches, as described by phenomenology, both of which we can only praise and expand. . . . Rather than dividing philosophy and theology up into two utterly separate worlds, we will practice the one as well as the other, seeking in ourselves a new mode of unity.

2

As a mode of unity, Falque here implicitly criticizes those accused of the “theological turn” who nonetheless maintained a strict demarcation between their more philosophical and their explicitly theological works—Lévinas, Ricoeur, even perhaps Marion. He further contends that such an endeavor must not only be embraced by phenomenologists, but also made explicit, and to welcome the transformation that it may elicit in their philosophical works:

The “crossing of the Rubicon”—from philosophy to theology and vice versa—is for myself, as for anyone, all the more justified insofar as we make explicit where we went and are able also to return after having been transformed. The better one theologizes, the more one philosophizes.

3

Here Falque distinguishes himself most explicitly from Jean-Luc Marion, whom he less-than-subtly accuses of engaging in theological projects while nonetheless masquerading as a philosopher, failing to acknowledge his theological tendencies (if not a theological method outright as a phenomenologist from the perspective of transcendence). In contradistinction to theological turn phenomenolgists, Falque wryly observes that “the muddying of the boundaries is not a consequence of the return to the philosophy of religious experience, but a result of the mask worn by a philosophy that does not admit to being theological, albeit in the passage of time and in the unity of the same person or researcher,”

The theological turn is not, in any case, to be either taken or left behind . . . it could well be the case that one is more of a philosopher by being at the same time a theologian, in the unity of the same person, than by always trying to pass as nothing but a philosopher while in fact also practicing theology.

5

Falque thus criticizes this failure to acknowledge the traversal of a boundary, the previous generation’s refusal to recognize the potential for transformation in favor of strictly segregating one’s oeuvre between the disciplines or clandestinely engaging in one while masquerading in the other. Instead, Falque presses further and boldly makes the crossing.

Unique amongst the so-called “theological turn phenomenologists,” Falque brazenly takes this step, arguing both for the need to embrace theology in philosophy (and vice-versa), but also to do so explicitly. Such a step, according to Falque, enables the traversing of a previously-verboten boundary and consequently opens the door to mutual transformation and revelation. He laments that “philosophy has restricted itself to the threshold of the theological discipline, which could actually be practiced at the very same time. This step had to be taken. Elsewhere I have already undertaken part of the crossing. All that was missing was its justification.”

Beyond the more apologetic aspects of Falque’s work, any discussion of philosophy and theology in French phenomenology (irrespective of the theological turn) must acknowledge the cultural and academic milieu in which these debates occur. Much like his phenomenological forebears Lévinas, Henry, Chrétien, Marion, and Ricoeur, Falque writes from within the climate of the French Academy and wider French culture, marked by rigid boundaries between creedal religious faith and laïcité / secularity. Despite such commonalities, while the beginnings of the theological turn met resistance and rejection (notably in the works of Dominique Janicaud in his Phénoménologie Éclatée and Le tournant théologique de la phénoménologie française), Falque belongs to a younger generation of phenomenologists for whom theology in phenomenology—while by no means mainstream or wholeheartedly embraced—is less polemically charged and more widely disseminated in academic philosophy. A notable difference thus becomes clear between Falque’s ability in twenty-first-century France to be engaged more directly with theology without “masquerading” or “muddying the boundaries” from those theological turn phenomenologists of the post-War era.

More significantly, in addition to the generational gap to contextualize Falque’s writing within France, I also suggest a geographical and cultural particularity that heavily colors his perspective. I pose the question as to whether these methodological considerations are pervasive and systemic to phenomenology, or rather a more idiosyncratic manifestation of the French academy given the prevailing structures and attitudes of the French system, cultural values, laïcité, and espoused secularity—an attitude which does not exist nearly as strongly (if at all) in philosophy of religion or religious experience outside of France.

Nonetheless, I leave such observations aside in favor of more substantial critique. I merely note these prefatory remarks—admittedly somewhat longer than I had wished—as something worth acknowledging to ground the context and climate out of which Falque writes.

- Porous Borders: A New Model

Yet what, precisely, does Falque propose concerning the traversal of this boundary and the relationship between philosophy and theology? I make this point briefly in order to use it as a springboard for critique and further conversation. Nonetheless, it is critical to understand Falque’s novel contributions to this understanding of the disciplines’ relationship.

Falque rejects any form of a strict demarcation devoid of contact between philosophy and theology, and equally so the denigration of one in favor of the other (either by secular philosophy of theology as unsubstantiated mere belief or superstition, or by theology of philosophy as banality or a preparatory handmaiden). In order to clarify the singular uniqueness of Falque’s position, consider what I discern as the five prevailing historical models for the relationship, all of which Falque rejects:

- Philosophy serves as a preparatory stepping stone to the more advanced discipline of theology, much as grammar serves as preparatory to rhetoric (Handmaiden model);

- Theology enables the consummation or completion of the work begun by philosophy, and theology builds upon the groundwork of philosophy and brings it to the heights it could not otherwise achieve on its own (Handmaiden model);

- Ultimately there should be no distinction between them, arriving at a complete subsumption or synthesis of the two (Mysticism model);

- Theology and philosophy, faith and reason, operate on two completely separate spheres and are absolutely distinct—contact is neither desirable nor even possible (Modernism model);

- A complementary relationship between two irreducible yet mutually-supportive disciplines, the “two wings by which the human spirit is raised up toward the contemplation of truth”9 (Catholic model)

Falque, for his part, rejects all of the above in favor of a transformative model, one of porous boundaries that maintains distinction and yet enables a mutuality. He advocates the maintenance of the boundaries only so that they may be traversed and continually recrossed—“there and back again”—a porous border across which we are neither aliens nor sojourners, neither refugees nor immigrants, but rather a foreign exchange of travelers transformed by the foreign. He asks, “How does Christian belief . . . change [philosophical] belief per se in any way? In other words, does religious faith, or more precisely confessing faith, only extend or complete philosophical faith—or does it not rather transform it?”

Thus Falque’s conception of the relationship between philosophy and theology is transformative rather than supplemental, metamorphosed rather than completed, mutual rather than complementary, demarcated, segregated, or antagonistic. With at least this (brief) sketch of the relationship between the two in mind, I now turn to consider the laudatory and beneficial contributions of Falque’s perspective.

III. “Now More than Ever”: Dialogue across Difference

Elsewhere I have praised the many insightful contributions of Falque’s larger phenomenological project, specifically in its reclamation of the dignity (and even the priority) of the body in its incarnate finitude, as well as his attempts in promoting a theological phenomenology grounded in the perspective of immanent human experience.

Given Falque’s repeated emphasis on traversing seemingly solidified, unquestionable boundaries, I shall assess how his thought provides a potentially fruitful avenue to foster encounter, dialogue, and even conversion (or “transformation,” to use Falque’s terminology) across insurmountable barriers—dialogue across difference, encounter in place of estrangement, and mutual recognition overcoming rigid segregation.

Falque accomplishes this forcefully and thoroughly throughout Crossing the Rubicon by his repeated emphasis on a commonly-recognized grounding in a form of faith—philosophical faith in the experience of the world before any creedal confession or theological faith. In doing so, Falque emphasizes a shared starting point of immanence and finding a common ground whence to facilitate encounter, dialogue, and mutual recognition. A characteristically Falquean move, this builds upon his previous claims of finding a common ground in human finitude and embodiment as a starting point for dialogue instead of shared transcendent concepts, as he articulates in his Passeur de Gethsémani.

Falque makes this most explicit in his exposition of the philosophical (dare I say, secular) faith that undergirds not just a theological faith and religious belief, but of necessity all human experience. He thus contends that, even with respect to an atheistic or fully secular philosophy, a common act of faith operates:

I could never believe that I do not believe in the world. A “universal ground of belief in the world” remains non reducible . . . the idea of an original faith in the world, or rather trust in the belief that I have of the world, makes the world paradoxically the highest and the most certain of truths in an originary attitude of trust rather than mistrust. That this faith may be philosophical and not only religious is one of the great lessons of phenomenology.

14

Falque thus highlights an implicit yet oftentimes unrecognized common ground—an “originary attitude of trust rather than mistrust”—that provides a common grounding for seemingly opposed or even contradictory beliefs. This opens up a common space for encounter and dialogue across difference. Of necessity, Falque contends that at the root of any form of theological faith or creedal confession shares a rooted patrimony with philosophical, secular “faith” in the world. A secular philosophical position, similarly, shares in the belief structure of a form of faith—faith in the world, in my own existence, in my experience, in the existence of others. For Falque, this patrimony undergirds both philosophy and theology:

There is no confessing faith outside of an original philosophical faith. A common ground of believing always precedes the decided act of believing. To recognize oneself as “believing otherwise” is then not to disregard faith or to condemn the so-called unbeliever. This position is neither a kind of ostracism nor a kind of conformism, nor does it aim to relativize . . . believing theologically in God rests on first believing philosophically in the world or in others.

15

This shared patrimony of faith in the world serves as a starting point—grounded in Falque’s characteristic emphasis on finitude and incarnation—that human beings share phenomenologically, irrespective of creedal confession. Rather than starting from irreconcilable opposing tenets of belief—immanence versus transcendence, atheism versus theism, secularism versus creed—Falque uncovers a common ground where estrangement yields to encounter, a commonality to be shared in lieu of differences to be debated that can overcome antagonism from both sides:

Religious faith, often wrongly mistrusting the world and the ordinary belief of humans, should recognize first the trusting attitude that abides in each and every one’s originary philosophical faith—whether a believer or not. The belief of all humans in others and the world, if it is simply sympathy, always leads to the belief that others are rather than they are not, and inclines humans to entrust themselves to the world rather than distrust it.

16

This act of trust rather than mistrust and a recognition of a common faith removes a certain antagonism or even haughtiness of religious faith over and against secular philosophical faith. By opening up a space for common encounter, an attitude of trust, and a means of dialogue through shared concepts and perspectives, Falque has already overcome a history of remarkable segregation and entrenchment between philosophy and theology. Falque presses even further by actually taking the step—traversing the Rubicon and being the “voyager” to travel into foreign land. In doing so he perceives not only the opportunity, but also the very necessity of theology and faith to ground itself in these more immanent philosophical perspectives and concepts:

Finitude thus serves as the beginning of philosophy as well as theology insofar as no theologoumenon has any meaning outside of a lived experience or a philosophical “existential” which gives it meaning . . . the body for Incarnation, anguish for Gethsemane, eros for the Eucharist, birth for the Resurrection, wandering for sin, childhood for the Kingdom. In sum, it should be clear that a phenomenology from below precedes and grounds any theology from above.

17

Not only does this dialogue overcome differences, for Falque it is absolutely essential to any attempt at theology, “Since God became man . . . it is first through the human that we reach God, only seeing after the fact and with a heart still burning that he was already walking at out side when he was speaking to us along the way (Lk 24:32).”

Granted, not all interlocutors will share that position, but the ability to open a common ground for fruitful encounters and dialogue is certainly remarkable over an issue and in an era so heavily polarized—and not just in the realm of theoretical academic debates. I cannot help but wondering whether the implications of such a prospect for dialogue hold untapped potential for other historically-estranged or opposed groups: theism and atheism, various and differing creedal faiths, the Church and postmodernism, or even into the realm of contemporary politics, to name a few.

IV. A Concluding Question

Despite this, is there not a necessary hostility—or perhaps less charged, a beneficial antagonism—that we should maintain between theology and philosophy?

Crossing the Rubicon provides an exemplary model that enables dialogue across difference, though such a movement also exposes a necessary inner tension that appears irresolvable in the relationship between philosophy and theology—a mutual necessity but also a mutual hostility or antagonism, or (at best) a mutual opposition and critique.

I fear that, in some cases, Falque advocates an overly optimistic view of the potential for this relationship. He concludes, “Entente [in French] has two meanings: listening but also agreement. In this double sense, we should listen for and agree on what such a crossing of the ford might have demanded, or yet led us to believe or think.”

The stranger’s country [become] my own land, without confining me to the status of an expatriate. Of course, no one will forget his country of origin. But we will also remember that only our country of origin makes the opportunity to travel possible, and that we must finally oppose patriotism’s code of silence and disciplinary boundaries and divisions, the transformation of ourselves by that which is foreign.

20

While optimistic and merely a metaphor, we know all too well that this is not always the case. What of the foreigner maligned and oppressed, rejected and estranged, or the refugee rejected and deported? Contemporary philosophical considerations of hospitality, hostility, hostipitality reveal the nebulous nature of these encounters, while the trope of the oppressed “alien and sojourner” is no stranger to theology, either. Perhaps caution is merited, and discernment regarding the value of antagonism and discord.

Such hostility and antagonism are not necessarily evils to be avoided. Mutual critique and accountability prove beneficial, and even necessary, in calling another to account or in fraternal correction. Could not some “hostility” provide the necessary corrective against ideological blindness, or misguided dogmatism?

On this point, I consider the aptness of Falque’s title: Crossing the Rubicon. The allusion to this monumental and mythologized moment of history captures only partially what Falque advocates and embraces: an irrevocable step that constitutes an act of war against the status quo, one that unsettles and provokes, yet nonetheless one that leads to an unquestioning transformation of both the traverser and the traversed—for neither General Julius Caesar nor the Roman Republic were ever the same after that moment. But let us not overlook the necessarily hostile nature of this exchange—or, better yet, this irrevocable incursion and the civil war that transpired. Without antagonism and hostility in the relationship, perhaps Falque advocates not so much crossing the Rubicon as the more docile foreign exchange of crossing the Schengen zone.

Such comments should not be taken to set up a combative relationship with the text in question, and I caution that I make this observation not as a criticism, but rather as a prefatory note to ground and to frame both Falque’s claims and my assessments that follow. In fact, I have written elsewhere in strong defense of Falque’s reclamation of the body and his emphasis on an immanent phenomenological perspective. See William C. Woody, SJ, “Embracing Finitude: Falque’s Phenomenology and the Suffering ‘God with Us,’” in Evil, Fallenness, and Finitude, ed. Bruce Ellis Benson and B. Keith Putt (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017), 115–34.↩

Emmanuel Falque, Crossing the Rubicon: The Borderlands of Philosophy and Theology, trans. Reuben Shank (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 158.↩

Ibid., 107. Emphasis added.↩

Ibid.↩

Ibid., 123.↩

Ibid., 158. Emphasis added.↩

And here I note, while anecdotal and experiential evidence, the observation that for the first two conferences of the International Network for Philosophy of Religion in Paris, France, every paper from a French author or presenter focused on methodological justification, while for the Americans and Australians such justification was taken for granted and moved into the realm of application and description.↩

The hermeneutic grounding of the author or, as Richard Kearney asks, “D’où parlez-vous?”↩

Pope Saint John Paul II, Fides et Ratio, §1. Falque still recognizes and advocates a level of complementarity between philosophy and theology, though he also emphasizes a transformative aspect that goes beyond mere complementarity.↩

Falque, Crossing the Rubicon, 99.↩

ibid.↩

Ibid., 124.↩

See above, note 1.↩

Falque, Crossing the Rubicon, 83.↩

Ibid., 99.↩

Ibid., 83.↩

Ibid., 124.↩

Ibid., 152.↩

Ibid., 153.↩

Ibid., 152.↩

10.23.18 | Bruce Ellis Benson

Response

Always Believing

How to Keep Crossing the Rubicon

At the center of Crossing the Rubicon is a section titled “Deciding.” The first subsection is titled “Always Believing.” Falque cites the challenge, in effect, issued by Pascal: you can either believe or not believe. You have a choice. Yet this choice is based on what Falque calls the “non-choice,” the pressure of having to choose even if one does not wish to do so. Yet this non-choice is even more basic than that in believing in God. For, as Husserl reminds us, we always (already) have an Urdoxa regarding the world. Falque quotes Husserl as saying “an actual world always precedes cognitive activity as its universal ground, and this means first of all a ground of universal passive belief.” There is a Urglaube or primal belief that is central to human existence. What I find particularly interesting about this section is that Falque’s attention is really turned in a very different direction than the hermeneutics of suspicion. Of course, given the ubiquity of “fake news” and the seeming possibility of people creating and living in alternative realities, one might think that a hermeneutics of suspicion is precisely what we need now. But one can (I think quite rightly) counter that, to a great extent, it is suspicion gone wild that has led to this state of affairs. We forget that, even for the ones with whom we most disagree, our shared beliefs far outweigh our differences. Instead, we focus on what separates us, and then wonder why we can’t have any meaningful dialogue. Admittedly, it is hard in this environment of distrust for people (on whatever side) to see that their unity outweighs their disunity. Yet Falque reminds us that belief—of a simple ordinary human sort—is much more basic than disbelief. Even to disbelieve is always already to believe. He puts this very forcefully when he writes: “The idea of an original faith in the world, or rather trust in the belief that I have of the world, makes the world paradoxically the highest and the most certain of truths in an originary attitude of trust rather than mistrust” (83). Thus, one can speak of a “philosophical faith.” Before we ever get to a specific belief like the belief in God, we have a fundamental belief that there is a world and that we are part of it. We can doubt specific sensory knowledge, but we fundamentally have to believe that, by and large, are senses can be trusted.

If Falque is right, then the difference between the believer and the “non-believer” is already problematic. First, if we are all believers, then this terminology may not be completely helpful (and, often, terminology like “believer” and “non-believer” is simply used as a cudgel against the people we don’t like). Second, believing is not something that one does simply on one’s own. We are always part of a community of believers, whether this be a theological, philosophical, or scientific community. After all, to “believe” in the scientific method is not to believe in something that can be proven to be true, except by arguing that it produces good results. But I suspect that believers of any sort (Democrat or Republican, for instance) think that their respective beliefs produce good results and so have proven to be right. Third, it is not always clear the extent to which one believes anything. One can be a religious believer and still have doubts about major aspects of the faith. Even atheists can have doubts! Speaking personally, Thomas Nagel talks of his “fear” of religion, which he distinguishes from “hostility” toward organized religions as opposed to “fear of religion itself.” He goes on: “I speak from experience, being strongly subject to this fear myself: I want atheism to be true and am made uneasy by the fact that some of the most intelligent and well-informed people I know are religious believers. It isn’t just that I don’t believe in God and, naturally, hope that I’m right in my belief. It’s that I hope there is no God! I don’t want there to be a God; I don’t want the universe to be like that.”

Falque wants to move away from any kind of dialogue between philosophy and theology that is designed to “convert” the other. He also wishes to get rid of unhelpful stereotypes about “infidels” versus “believers.” Instead, philosophy can learn from theology and theology can learn from philosophy. In our time, theologians do much more in the way of description in their theology than in the past. And philosophers can ask questions about theological or holy things. One doesn’t have to be a believer in order to have something to say on the topic. So Falque suggests a “philosophy of the threshold” (139), one that gets beyond the model “where the philosopher opens and the theologian fills” (140). After saying many positive things about Ricoeur’s contribution, Falque claims that he only opens the threshold, leaving it to theologians to fill in the void. Even Marion, says Falque, keeps his theological texts separate from his philosophical ones. In order to prove his point, he turns to the classic distinction Pascal makes between the “God of the philosophers” and the “God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob.” Falque notes that, if one studies the distinction Pascal is trying to make, it is not completely clear that there really is a difference here such that one could label one as true God and the other as an onto-theological God.

“The more we theologize, the better we philosophize,” says Falque (25) and comes to a section toward the end of the book with that very name. That statement about theologizing and philosophizing should “serve as the leitmotiv for this liberated theology” (148). Falque calls it the principle of proportionality. He makes it clear that crossing the Rubicon is not a one-way, one-off sort of thing. Instead, it needs to be continually crossed and re-crossed. Falque clearly self-identifies as a philosopher. He is not interested in blurring the boundaries between philosophy and theology so that they no longer maintain their respective identities. But he believes that the time for “conquest” is past and now is the time for a generous spirit on both “sides.” In contrast to “claims of a liberation of philosophy by theology,” Falque proposes a liberation of theology by philosophy that provides an analysis of religious experience. This does not mean that philosophy now becomes simply ancillary to theology. Instead, the goal is to “let themselves be transformed—each by the other” (151). More specifically, he goes on to say that “the [philosopher] will teach the [theologian] about the human journey. The [theologian] will make the [philosopher] see that he cannot refuse to open himself—upon a decision, of course (Chapter 4, sect. 14)—to the transcendence of the One who comes to ‘metamorphose’ everything” (151).

However Falque wishes to “name” his views—as postmodern or some other term—it is clear that what he proposes is far removed from the climate and fears of modernity. Instead of seeing theology and philosophy as opposed (with each “side” claiming superiority), there is the recognition that each is valuable. There is also the recognition that “believers” and “non-believers” aren’t really all that far apart, even though neither category is reducible to the other. One can only hope that the way forward to which Falque points increasingly becomes a reality.

Thomas Nagel, The Last Word (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 130.↩

10.23.18 | Emmanuel Falque

Reply

To Be Modern Differently

I want to thank and congratulate Bruce Ellis Benson for putting his finger on an essential point and difficulty in Crossing the Rubicon. If we are “always believing,” as the title of the third chapter of the book suggests, what is specifically Christian about this? Is belief in the world, in the other, or in a project identical to belief in God?

What really is important for me to underline—as Bruce Benson stresses—is that no point of departure is ever neutral. Maybe this was the limitation of the total absence of presuppositions that the early Husserl claimed in the reduction and the epochē and to which he returned with the Urdoxa or the hypothesis of an irreducible belief by which we are all constituted. There is a “philosophical faith,” as Merleau-Ponty underlines in The Visible and the Invisible, and it this belief that propels us.

Benson is right that this seems to claim less a Christian particularity than it recognizes that we are all first “fellow human” (cf. Bernanos) and that in this respect the believer in God cannot necessarily claim something “more” but rather something “different.” On this also Merleau-Ponty has much to teach us. As long as religious believers, claiming to “have faith,” remain in an “overbearing transcendence” relative to non-believers, they remain always in a kind of “condescension,” in the form of “fear” or “withdrawal,” relative to those who do not think like them. The unilateral situation of the believer to the non-believer who is not necessarily atheist but at least indifferent, is here condemned. Believers cannot simply demand of non-believers or unbelievers to “become like us,” while they do not want to be transformed by the other who dispenses with God or faith as proclaimed. Any dialogical situation requires a possible transformation of the interlocutors. The “reduction to the same” (Lévinas) exercised by believers provides plenty of reasons for making those who do not believe back off and hence to separate “believers” (in God) from non-believers or from those who believe differently (in the world, in the other, even in philosophy). The formulation of the human “always believing” thus seeks to unite rather than separate, although belief in the revealed is not to be identified with the simple faith shared by our common humanity.

In the third chapter of Metamorphosis of Finitude I have insisted against or beyond Henri de Lubac that we are no longer today in the “drama of atheist humanism” and that is because the times have changed. Certainly nothing is easier today, especially in the secularized world of Europe that tends to become generalized. Yet, even for the theologian, a “shared humanity” must take precedence over the simple fact of taking oneself to be “chosen,” “elected,” or “separated out.” What is proper to us relies first on what is shared in common. Christianity sometimes begins to close in on its singular identity when it forgets this.

Is there then a “complementarity” between philosophy and theology as Benson seems to indicate? On this point we can entirely agree. Not only should theology not complete philosophy (hence the criticism of the philosophies of the threshold), but it should also not claim a leap that theology or revelation alone can make happen (hence the criticism of the philosophies of the leap). This is a model of encounter and transformation rather than completion or rupture. Admittedly, the Institut catholique is not very far from the Sorbonne, as the contribution rightly points out. Yet, the Luxembourg Gardens between them have to be crossed and that is a kind of Rubicon where we must meet. God would like to join us, but we must first present humanity as it is, if it is also to be transformed or metamorphosed.

Am I “modern” or “post-modern,” if I am asked what to call myself? Such labels always have the danger of prescribing things and not allowing thought to go about its own way. “Modern” or “postmodern”—it matters little. Maybe the implicit perspective developed here is that of being “modern otherwise.” For the dialogue about the human cannot be confined into professional certainties, which sometimes have the effect of separating the believer from a shared humanity. The “positive uncertainty” must serve today as a point of departure rather than any “negative certainty.” For uncertainty, such as it is shared among all humans, “always believing” in the other and the world (Urdoxa), properly speaking does not reduce the confessing believer but inhabits him or her differently. To be “modern otherwise” means neither to flee nor to marry modernity, but only to enter into an act of “discernment” whether the divine can still be affirmed or even to discover the human as still worthy of dignity and of encounter.