Symposium Introduction

It’s November 2019 in Seattle, Washington. I am attending the annual meetings of my primary professional organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). It is the first time I have spoken to a large gathering of fellow anthropologists since my diagnosis, in 2016, with a genetic connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. For almost the entire previous decade, my life has been occupied with an increasingly unruly body and a complicated, traumatizing medical system; all the plans I had to continue fieldwork in north India have dissipated into the swirl of physician apathy around me: I can’t help you. I don’t know why this is happening to you. Have you tried yoga or meditation? About a month before the meetings, an experimental new treatment has helped my mobility levels; I don’t bring my wheelchair to the conference. I stand in front of an audience without assistance for the first time in years.

It’s not just the first time I’m in front of a professional audience in a while. It’s also the first time I am calling on my training—the training that also built my body, along with my special genetic coding, beginning in ballet and tap lessons at age five—as a dancer, a stage performer. I haven’t “performed,” since I left my playwrighting major in 1995, seduced away by my love for cultural anthropology. But for this presentation, behind me on a large screen, film sequences are spliced together, my (pre-Covid-19) largely housebound life of the previous several years flashing for all to see. Knitting, which I do to pass the time when my hands cooperate; untangling balls of yarn; wrapping a broken wrist (a constant risk, given my condition) in an Ace bandage. Next comes rare footage of myself at age seventeen, dancing on a stage, seeming graceful but now, I can see – I point out to the audience – a body riddled with signs of a deeply problematic hypermobility in almost every joint.

I talk about how embodied autoethnography and spoken word performance are helping me deal with the ethical quagmire of studying a thing that I also am: a confused disabled chronically ill woman in a lot of pain, looking for answers in social media forums and from international specialists and from within my own family history. I talk about the pain—pain so fierce even the guys writing the objective pain scales feel sorry for me. Pain that can’t be written in realist genres so I have to resort to the imagery of childhood nightmares about cartoon villains. And I talk about the loss. The career, travel, more children, I might have had that will never be.

More remarkable than standing on my often-pained legs is that I have given myself permission to put all these things into this presentation: the dancer, the anthropologist, the woman in pain. They’re all on the dais with me. We can say a lot about how far various academic disciplines have come in embracing novel forms of research and presentation. But still. this talk is unusual. How did it come to be?

It was born seven months earlier, when Dorinne Kondo contacted me, having been given my info by a close mutual friend, who told her that I was also working with genre-bending forms of ethnography. That I was also dealing with a rapidly changing adult body that was reshaping the lines between work, art, and survival in my life. “I’m going to put together a panel,” she said, inviting me to contribute. And then she suggested that presentations need not be traditional conference papers – that we might present in whatever genre best suited the work we were doing. A simple suggestion, really, that, it is no exaggeration to say, has changed my life.

*

I read Worldmaking after my first conversation and email exchanges with Dorinne and it was like coming home, attending a joyful all-out dance party, getting a backstage pass to some of the most important productions in recent US theater history, and being deeply challenged as an aspiring anti-racist scholar, all at the same time. So when I heard that Syndicate was interested in convening a symposium about the book, I jumped at the chance to help organize it, a task that has truly been my great privilege. While the pieces collected here will not allow readers to turn away from the realities of anti-Blackness, Asian-hate, the ongoing extractions of settler colonialism, and their intersection with so many other forms of racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, economic oppression and all the structures of privilege and violent erasure that tell people “this is not your world, you have no right to make it,” they will also bring, I believe, great joy.

In recent conversations with Dorinne, we have discussed the way that the kind of joy that arises from work like Worldmaking does not mean happiness. Joy, in this sense, is the erotic, as imagined by Audre Lorde (also referenced in Lin’s piece below): that possibility of connection and meaning that gets you out of bed in the morning in the face of the horror show. These artistic-scholarly responses to Worldmaking also produce joy – the kind that rises up when people tell the truth about a thing in a creative way so that we can feel our connection and distance at the same time: reparative creativity, a concept mentioned in every piece as a keystone of this important book.

In her discussion of the playwrighting and performance practices of Anna Deavere Smith, Kondo describes this simultaneous move in which Smith, or any of us engaged in the work of making art and scholarship rooted in social relationships, leap toward one another through language or performance or embodied listening, without erasing or collapsing power-laden difference. To make these leaps, artist-scholars must practice what she calls “radical availability to others” (106). And, indeed, while none of the authors in this symposium speak from exactly the same racial, social, economic, or historical position, they have made themselves radically available to Kondo’s text, to one another, and to you, the readers. The results are extraordinary.

It is also important to mention that Kondo’s descriptions of working on the dramaturgical teams of both Smith and David Henry Hwang are ethnographic gold that should be taught regularly in performance studies, theater, and anthropology departments around the world.

*

As she says in Worldmaking, one aspect of the theater that drew Kondo from being an observer to a creator of theater is its deep, essential sociality—the way a performance relies on the energy and expertise of so many people working together for a common goal, even if it is no obvious at the outset what that goal is. Kondo has taken that expertise and transferred it back into anthropology and allied fields in such a way that on that stage in 2019 I could feel supported enough to try something I had literally never seen at a professional scholarly conference, something painfully self-revelatory, and feel supported, even joyous, about the whole thing. Her role in our field is path-breaking and her entire career stands as a testament to the effort to create and support truly interdisciplinary work that refuses zealously guarded disciplinary borders—as an earlier-career scholar with the benefit of her mentorship, I can personally attest to the great gift she has given not only me, but so many others.

And look, Dorinne Kondo has done it yet again! Conjured a magical group of serious play-mates and interlocutors to discuss some of the highlights of Worldmaking! The contributions gathered here—which Kondo herself has called an almost embarrassing wealth of intellectual and artistic riches—and the layered, rich, diverse meanings they have all taken from this incomparably creative work—are a testament to Kondo’s importance as a scholar on and off the page. Following her visionary lead, most of the contributors here have chosen nontraditional forms for their responses, from a short play (Lin) to a personal “confession” (Singh) to an artful reflection on the crafting/making of bodies as reparative creativity as seen in the bodybuilding practices of Tommy Kono (Chow). And the dialogue between Kondo and Christen Smith about the staging of “Seamless” at the 2018 AAA, as well as the birth of Wakanda University, should be seen as no less than an oral history of a pivotal moment in the history of anthropology in the United States for the way it is situated in pressing questions about the discipline’s ongoing anti-Black racism, colonial “othering,” and practices of extractive knowledge-making.

*

I could not be happier to share this set of essays with you and to express my gratitude to my friend, mentor, and teacher, Dorinne Kondo.

7.4.22 |

Response

On Late Bloomers

Here’s a secret: I have, for as long as I can remember, felt the deepest desire to perform on stage. And I have, for as long as I can remember, felt ashamed of this desire.

I had one opportunity, at age five, to perform in a church Christmas pageant. My mother desired community for her otherwise alienated mixed-race family and thought church the answer to her wish for inclusion. And so, as an otherwise nonreligious brood, we were suddenly thrust into a world of Christian values and stringent whiteness. By the year’s end, realizing that we were being taught in Sunday school that our Sikh father and Jewish grandmother were going to burn in the fiery pits of hell, my mother withdrew us from the church.

In the months before dropping out, I was elated to be included (along with every other child) in the pageant. Cast as a little lamb from the flock of David, I spent hours memorizing my lines and working on my delivery while my mother glued white cotton balls on a pillowcase and cut out holes for my head and my arms. When pageant day arrived, I slipped on my cotton-ball frock, and hardly cared that my little legs, arms, and head poking through revealed me as the only little brown lamb in the otherwise homogenous flock. At the end of the pageant, the minister’s blue-eyed daughter took center stage, raised her arms high in the air, and belted out from the top of her lungs the final lines of Christian conquest: Today the jungle! Tomorrow the world! Then in unified affirmation of a global conquest to come, all of us echoed her: Tomorrow the world! Draw curtain.

Cut to a decade later, in the early 1990s. I am a troubled teenager bouncing between the offices of the principal and the guidance counselor. I am a disruptive joker in class, cheat on tests for fun, smoke cigarettes in plain sight of the school, ditch classes. But I have also developed a passionate and totally hidden penchant for drama. When the school announces it will stage a production of Anne of Green Gables, I know instantly in my bones that I can be Anne—that I can channel all of my angst and restlessness into this one crowning achievement, and that it will change the course of my otherwise wayward life. I will finally be good at something.

I practice obsessively for the audition, and swallow my pride when I sign up to perform in front of two male teachers with whom I am in disfavor. When the time comes, I shake with nervousness but force myself to become composed, singing about Anne’s first taste of ice cream: Ice cream! Is anything more de-lec-table than ice cream? Why, even the most respectable eat ice cream . . . I have no objective idea of how I am doing, but I am desperately hopeful. As I leave the room, just before the door latches, I hear the teachers break out into unrestrained laughter. And I understand what I hadn’t before—that a fat brown girl who has already been cast as bad is never going to get the part of a waifish redheaded heroin, is not even going to be allowed to play a marginal part in a play by and about good white folks.

I have returned to these formative scenes many times throughout my adulthood: The way I harmonized unwittingly with racism as a child, and later, how I was socially cast as bad, and then acted it out to perfection while being ridiculed for desiring something different. The way I was turned away and then turned myself away from theater’s brute whiteness. I think of them now, rereading Dorinne Kondo’s inspirational Worldmaking: Race, Performance, and the Work of Creativity, a book that most intimately reminds me of how much potential minoritized theater holds for what Dorinne calls reparative creativity, “a working through of life, death, power, connection, humor, joy, in the face of so much that would kill bodies and spirits, the political hope of ‘and yet?’”

Dorinne has herself traveled toward the theater in unexpected ways, first as an “objective” ethnographer working on the craft from a brainy height, and then as one who—despite her own psychic resistance—surprised herself by emerging as a passionate playwright. In the book’s “Overture,” she writes of the day she discovers another relation to theater:

I am here for the inaugural meeting of the first David Henry Hwang Playwriting Institute. Not, mind you, because I think I possess dormant playwriting talent, but because I can use it as a fieldwork technique: to meet people in Asian American theater, to find out about the pedagogies of playwriting, to learn the elements of the craft. No matter how embarrassing, I tell myself that it will be worthwhile for my ethnographic project. (1)

Yet by the second page of the book, our author is entirely ignited by the revelatory work of theater, and her own relation to the craft is radically transformed. No longer is she positioned as a reader and scholar, but as one who hears the scenes, who begins to craft them by and through her own body. So begins Worldmaking, with a scene of Dorinne’s own world shifting—suddenly, powerfully, unexpectedly—through the promises and possibilities of making minoritarian art. And there’s something for me, for us, in this revelation: an embrace of late bloomers, a reminder that we can find our ways toward creative practices and artful lives no matter our points of departure.

Reflecting on her own plays alongside those of David Henry Hwang and Anna Deavere Smith, Dorinne writes: “The work is not about a conventional hero journey in which an individual quest ends in triumphant resolution. All of us spotlight characters who are minoritarian subjects, and we eschew happy closure and epistemological certainty” (45). In Dorinne’s play Seamless, which amplifies and concludes Worldmaking, uncertainty and open-endedness are not the starting points but the horizons of the work. The protagonist, Diane, is a forty-something corporate lawyer who is professionally successful but lacks vital investment in life beyond her upward mobility. She wills herself toward the top of that world by eschewing the more intimate but no less political parts of her life. Seamless carefully and critically unstitches the neoliberal protagonist and ultimately invites her to dwell with the always incomplete, partially unknowable traces of history that she has disavowed in the effort to cast herself as flawless.

What is so brilliant about Seamless is the way that the violence of the Japanese Internment creeps into the play, eventually taking hold and rearing its head. Despite Diane’s willful desire not to learn this history or to see its lasting effects on her family, and despite her parents’ unrelenting need to bury the lived experience, this is a history that demands to be felt, to be vitally acknowledged and to be redressed through the figure of Diane, the one who once believed it was nothing more than a blip in history. By the end of the play, through a series of personal losses, professional choices, and historical discoveries, Diane emerges as quite another kind of human—one committed to sorting through the traces of the past, to making sense as best she can of her family’s fragmented history in order to tend to it differently and to live a life more consciously driven by ethics. Crucially for the praxis of reparative creativity, this is no simple tale of transformation and resolution; she is left not with a sutured end, but with a mess, an incomplete archive, a haunting, and a critical question: “How do these fragments go with all the other fragments?” (309). It is this question that names the ethical orientation of the play: the fragments exist as the messes that have made us, the ones we will never fully understand, but that invite (and sometimes demand) our attention and care. The end of Seamless is the start of something else, a life lived in and with the fragments of the past and in embrace of our messy, unfinished seams.

In Worldmaking, Dorinne-as-author and Diane-as-character both experience revelations that allow them to change course, pivoting toward a wider, more experimental kind of life-embrace. I am indebted to them both, to how in contact with them we are able to imagine our own future-pivots, the ways we might turn ourselves back to those hard, unreconciled pasts. Or how we might discover, suddenly, something so unexpected that we are brought into new forms of intimacy. How I might, after all, take the stage and experience it otherwise.

7.11.22 |

Response

Surviving, Repairing

London, 2020 / Xiamen, 1945

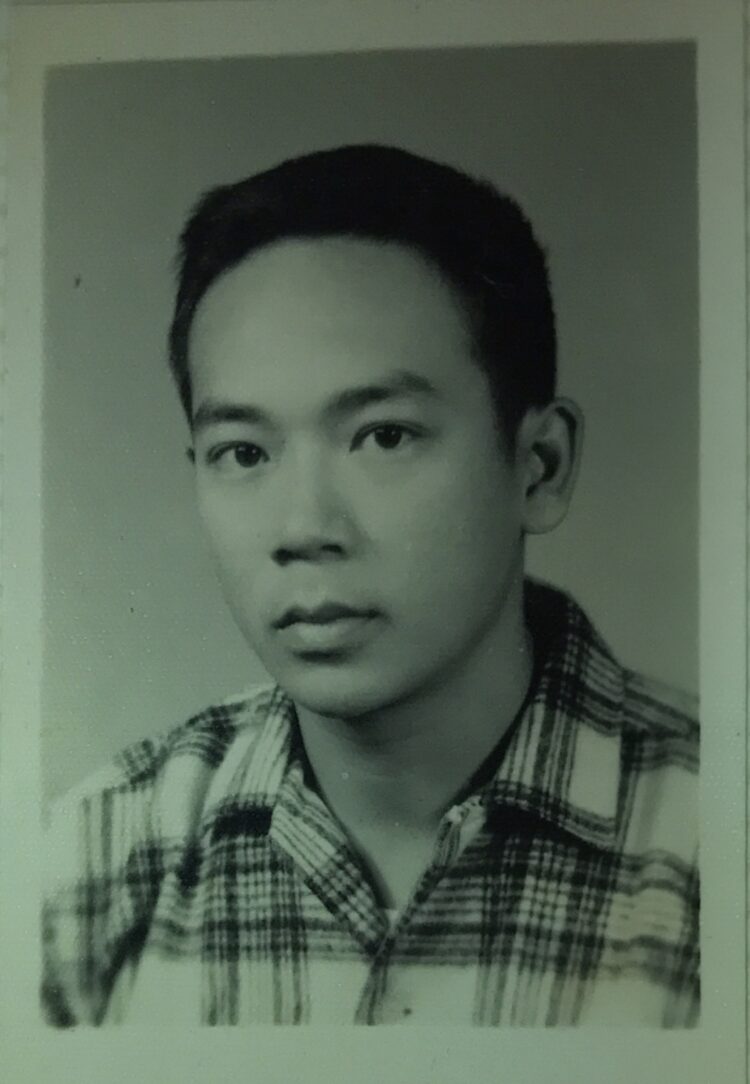

My first engagement with Dorinne Kondo’s Worldmaking was as an actor. In November of 2020, Dorinne was invited to give a virtual research seminar at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, and I played Ken, the father of the play’s protagonist, Diane Kubota, in a reading of excerpts of Seamless, her full-length play about Japanese internment and the afterlife of trauma. Ken reminded me strongly of my late father, despite the obvious differences. My dad was Chinese, born in Xiamen, China; he lived his adult life in Vancouver, Canada, not the United States; and he immigrated to North America as an adult, whereas Ken is a second-generation Japanese American (nisei). My dad was not an internee, like Ken. But nonetheless, imperialist violence haunted his life. His tales of childhood often resembled horrible Asian diasporic literary fiction written for white audiences, story after story of being displaced by the Second World War and growing up hungry and traumatized as a refugee in Hong Kong. Dorinne says that she wrote Ken (who is partially based on her own father) to communicate both a Nisei “emotional taciturnity and an opinionated liveliness” (228). I read this and related, hard. When my dad was lying in hospice, he told me that when he was a child and still living in Japanese-occupied Amoy (now Xiamen), he recalled running along the beach as American planes indiscriminately bombed the town. He remembered the heat on his back as he ran, barefoot, along the sand, shrapnel missing him by inches. This wasn’t, in fact, a horrible memory but a prelude to a rhapsody on the Southern Chinese seaside. “Ai-yahh, those days were fun,” he said. “But, the bombs though. . . . I survived!” he shrugged.

My emotional memory in place, I prepared for the reading by creating a gesture that would never be seen by any of the online audience, seeing as we were performing on Zoom, leaning back in my chair, resting my hands on my belly. It was just a small bit of work to prepare the character, but this kind of physical observation is not far from the acting methodologies of Anna Deavere Smith, with whom Dorinne worked as a dramaturge and whose process forms a long case study in Worldmaking. It is acting as meticulously paying attention, in “painstaking detail [to] a person’s language, speech patterns, mannerisms, without necessarily presuming to know their deep emotional conflicts” (102). Because, honestly, how could I presume to know, really, what is deep down in men like Ken Kubota or Martin Shui Fung Chow? But in the work of the gesture, I could perhaps travel part of the way, understanding what I had observed and seen, now in a felt, embodied and tacit way, the hands on the belly as a gesture of comfort and satisfaction, of listening quietly to the sounds of the house and the life you’ve built all around you after a good dinner. This was always my father’s deepest desire and wish; all he ever wanted for himself and for others: to have a good dinner. And he had many, many in his long life.

Hong Kong, 1952

The hopeful, thought-provoking and above all generous concept that Worldmaking gifts us is “reparative creativity”: “the ways artists make, unmake, remake race in their creative processes, in acts of always partial integration and repair” (5). Although, in qualitative research terms, Dorinne Kondo’s “field” is, like my own, the theater and its spaces of rehearsal, making, and staging, in this short piece of writing I want to instead elaborate the ways in which her work has accompanied me thinking through reparative acts, gestures and practices in the everyday experiences of racialized subjects, historically or in the present, ideas that Seamless embodies. In particular, her challenge to academic tropes of resistance has been especially productive to think with alongside my own embodied questioning of Asian racialization in the West and stereotypes of the model minority—especially in relation to figures and forms of Asian masculinity. As she writes, “The concept of resistance tends to reinscribe a whole (always already masculine) subject, who consciously fights the power” (227). Yet, if what constitutes the Asian American subject is its melancholic inability to come to terms with “loss,” its being already split, partial, unintegrated, then the trope of resistance might disregard how “what appears at first glance to be compliance or submission may produce unexpectedly subversive effects” (226–27). Dorinne asks: “But what about those who just tried to survive? To stay sane? To put one foot in front of the other?” (227).

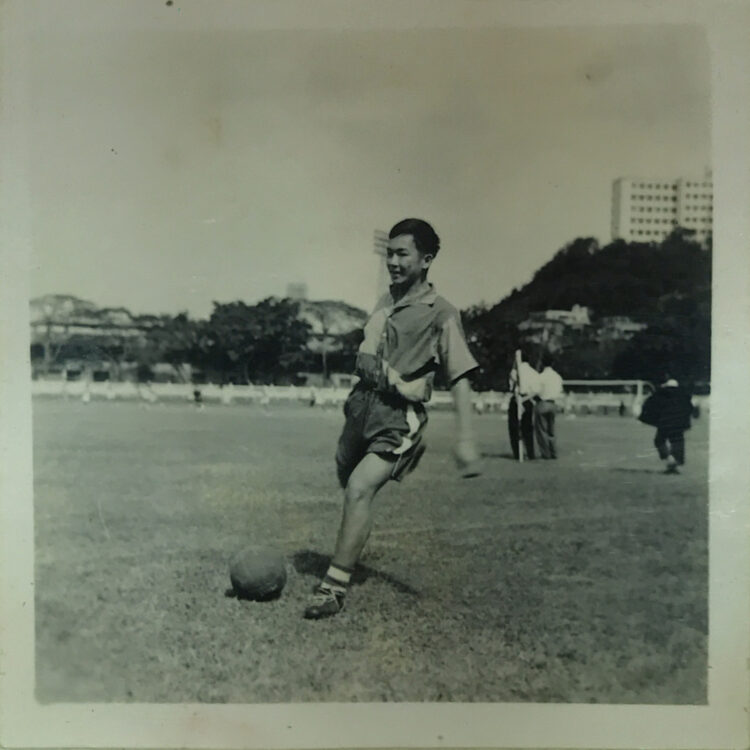

My dad had a tense relationship to resistance. Being a troublemaker—a quality I have most definitely inherited, much to the chagrin of both he and my mother—he resisted everything. He was gifted and clever but possessed of a stubbornness and desire for mischief, thus he was a problem child, and a problem teenager, and posed a problem for institutions like school, police, and family. When he was a boy, he fought the power in exceedingly creative ways. Once, in his bedbug-ridden Catholic boarding school in 1950s colonial Hong Kong, he captured as many of the pests as he could find, starved them, and then released them under the door of the headmaster’s bedroom. As an adult he continued to find himself a problem within institutions throughout his life. The Catholic boarding school was replaced by the factory, the union, and the Canadian government. He was explicitly a Communist, and from a young age, I knew Marx’s adage “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” But towards the end of his life—not coincidentally, as I became politicised—he became wary. Marx was replaced by a series of Chinese tropes about keeping your mouth shut: kah sue-sue, ki kun (wash your feet and go to sleep); pai gue gao chi, pai lang gao yeng yi (bad cucumbers have a lot of seeds, bad people have a lot of words); or he would simply say in English, “Close your mouth and close your heart.” He was, perhaps, scared of rocking the boat; after all, those institutions also held him, gave him stability, money, the ability to raise a spoiled Canadian son and educate him abroad.

Tule Lake, 1942

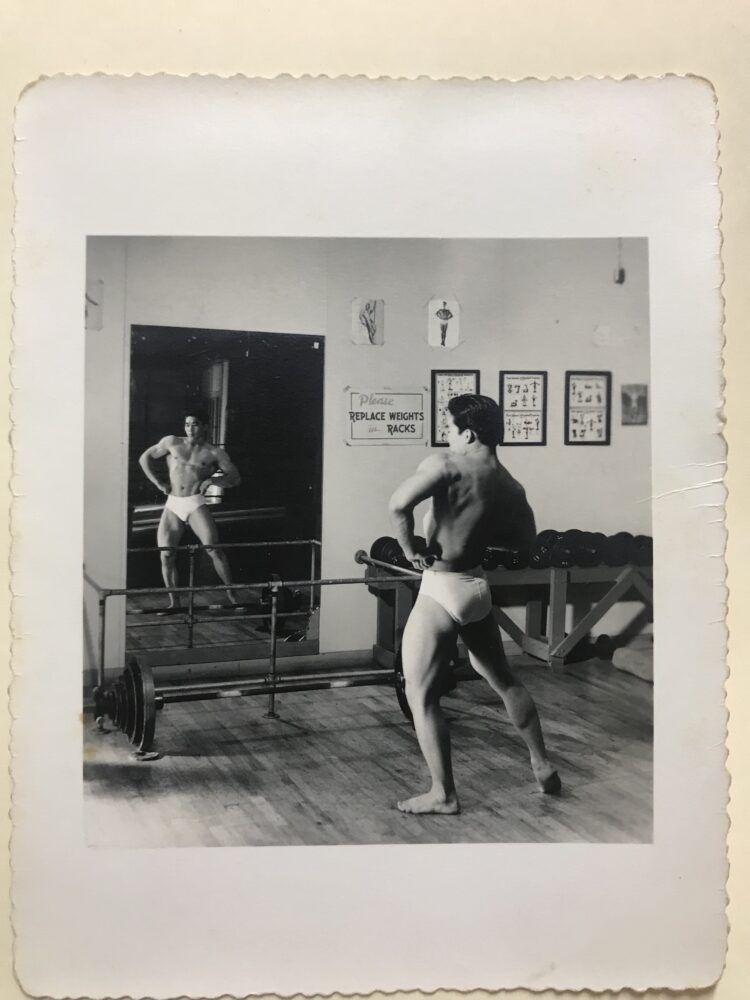

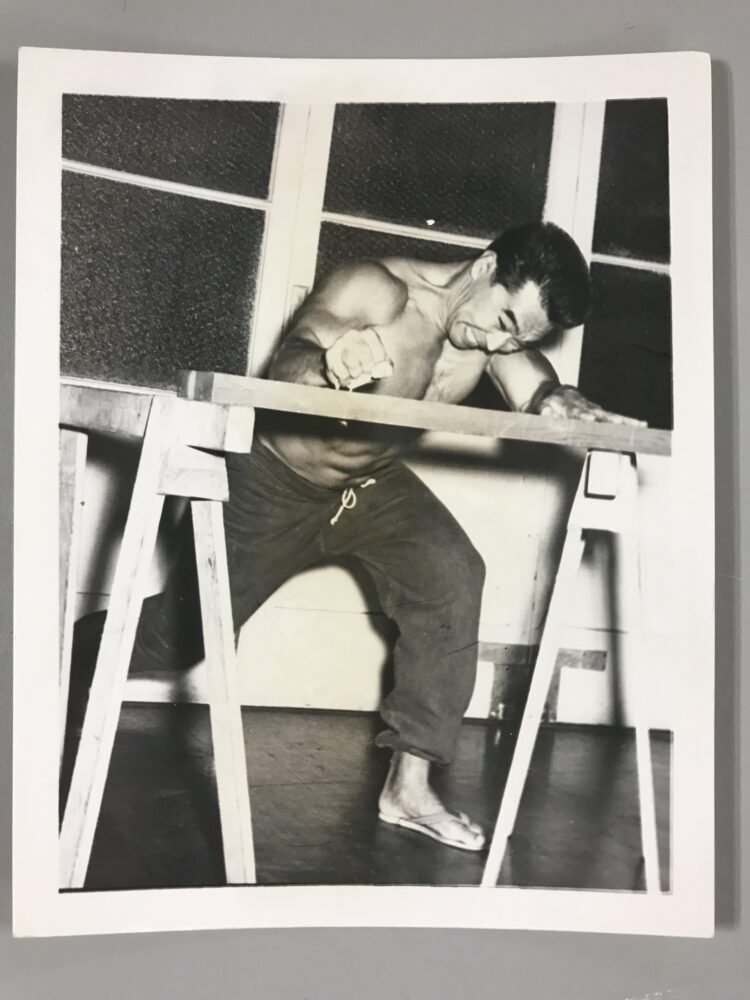

For the last two years I have been working on the archive of another recently departed Asian man: Tommy Kono, nisei, weightlifter, internee. Tommy died in 2017 and his papers were acquired by the H. J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at UT Austin, where I have been a visiting researcher on numerous occasions. Tommy Kono is perhaps the United States’ most celebrated weightlifter, setting records in four weight classes and earning two gold medals and one silver at the Summer Olympics between 1952–1960, as well as winning the World Weightlifting Championships every year from 1953–1959, and the Pan-American Games in 1955, 1959, and 1963. He was also successful in bodybuilding and was named Mr. Universe four times between 1954 and 1961.

Tommy Kono was also an internee. In 1942, at the age of twelve, Kono and his older twin brothers, John and Mark, and their issei parents, Kanichi and Ichini Kono, were relocated from their home in Sacramento, California, to Tule Lake War Relocation Center. It was in the camps that Kono learned to lift weights, from fellow internees, which transformed him from a skinny kid into a champion and a strapping example of Asian American masculinity. (Apparently, the desert air of Tule Lake also cured his asthma.) In Kono’s story, which has been repeated ad nauseum by physical culture media and institutions like the International Olympic Committee and USA Weightlifting, internment is reframed as transformation as well as assimilation.

Worldmaking transformed how I worked on, researched, engaged with, thought with Kono’s archive, his life, his legacy as an Asian American athlete. I will never be as successful a weightlifter as Kono. But I am a weightlifter, and what drew me in the first place to Kono’s archive was that he, a weightlifter who “looked like me,” at least in that racialized way where a Japanese person can “look like” a Chinese-Filipino person. Yet as I worked through his papers I began to recognize that my own desire for Kono to be a role model, a figure of resistance and representation for Asian men, was deeply problematic. My own reparative reading of Kono’s life and archive was speaking over his own reparative creativity. Dorinne’s working through race, trauma, and creative practice thus provided the key to a more nuanced understanding of Kondo’s story, not as assimilation, nor heroism, and more complex space of tension and negotiation of national ideologies and state-imposed violence. In other words, the gestures and movements of weightlifting and bodybuilding in the context of the camps might be reframed as a kind of minoritarian performance.

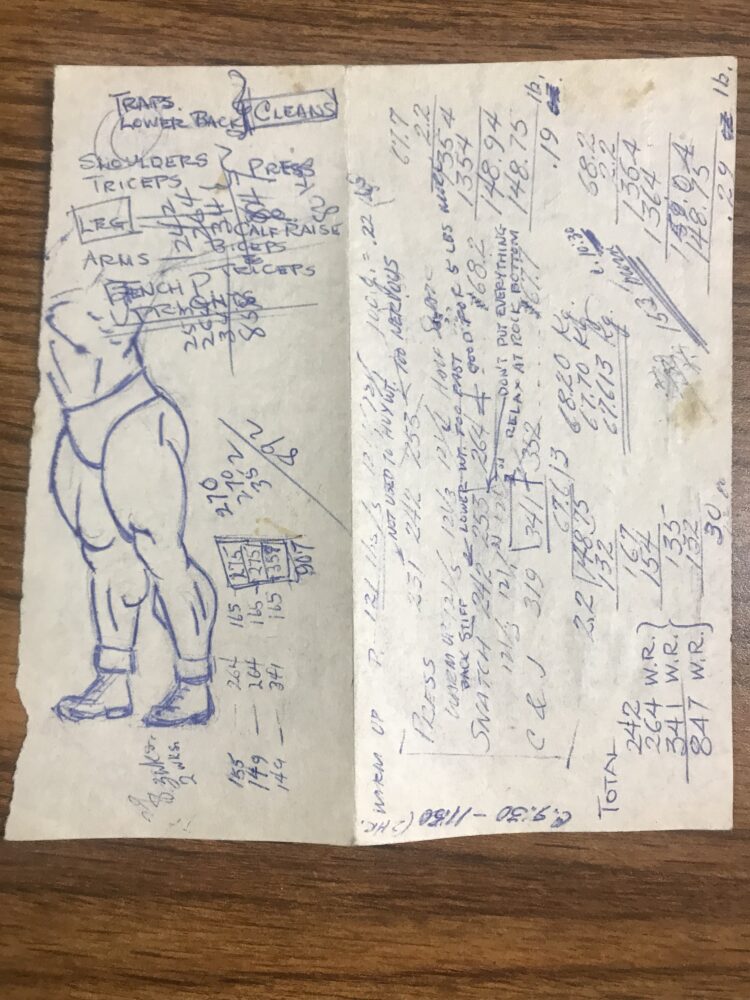

Tule Lake, 1942 / Hong Kong, 1952 / London, 2021

In a forthcoming article for Iron Game History, I describe a singular piece of evidence in Kono’s archive. It is a couple pages of yellowing notebook paper. On each page, Kono has drawn an outline of a body, with diagrammatic boxes and lines pointing to each body part. In each box there is a measurement. Over a period of sixteen months, the charts detail the expansion of Kono’s body. Chest, expanded, from 32” to 37.5”. Arm flexed, from 10” to 11”. Thigh, from 19” to 19.5”. These pages were drawn in 1943–1944. Tommy Kono would have been fourteen, maybe fifteen? I think about this youthful embrace of Kono’s own ability to transform himself as a minoritarian performance of hypertrophic expansion against the restriction of the camps as well as the boundaries of his own body. I think of the meticulous way Kono recreated the drawing of the body on each of the pages, his careful lettering as he measured his biceps, chest, quad, remaking himself, creating an image, a pose, a figure that would eventually enable others to see themselves too.

Reparative creativity, a “turn” of sorts, towards process, craft, labour, making, remaking, worldmaking, attends to what the racialized subject places value on. In other words, it indexes desire in the smallest, even imperceptible gesture and transformation. Desire is the force that motivates transformation in the present against all the evidence that such work will be futile. It moved my father, as a boy, to laboriously collect bedbugs in order to reshape the world of his boarding school headmasters, even if that reshaping amounted to little else than a radical redistribution of misery. But this is reparative creativity too—even if it is just a mean-spirited prank by a wicked mind—like the craftsmanship my father brought to everything his hands touched, whether in the engines he fixed as a mechanic or the food he cooked for his family.

When I step up to the barbell I am confronted with my body, as it is today: my hip, my lower back, my bad knee (the right one). Muscles, joints, tendons. I meet the gaze of others but above all I must see myself: I adjust my body, minutely, meticulously. I make a new image of myself in that moment, and over, and over. I must fail and in that realization make a new image of myself again. And then I pack my things up, shower, reenter the world, and know that tomorrow is another opportunity to do it again.

Artie Dreschler, “A Tribute to Tommy Kono,” TeamUSA.org / USA Weightlifting, April 27, 2016, https://www.teamusa.org/USA-Weightlifting/Features/2016/April/27/A-tribute-to-Tommy-Kono; International Olympic Committee, “Tommy Kono—Weightlifting,” August 3, 1952, republished on https://www.olympic.org/news/tommy-kono-weightlifting.↩

Joshua Chambers-Letson, A Race So Different: Performance and Law in Asian America (New York: NYU Press, 2013), 133.↩

7.18.22 |

Response

Being Kathleen

Reflections on Creative Play and the Reparative Possibilities of Theater in Anthropology

[10/27/18 email message from Dorinne Kondo] …writing to confirm: 1) christen, are you still ok with the swordfight? you are kathleen. could be fun!

“KATHLEEN GOTO—Japanese American, late 30s, assistant professor of psychology at Harvard. Initially a real character, then the devil on Diane’s shoulder” (Kondo 2018, “Seamless”)

Kathleen unsheathes a sword with her free hand and executes a dazzling sword play.

Performance/play is the devil on the anthropologist’s shoulder . . . and we all need the devil in our lives.

In 2018, I received an unexpected yet welcome email from Dorinne Kondo. Although we had not officially met, she was familiar with my work (and I had been very much inspired by hers) and she wrote to ask me to perform in a reading of her play Seamless as part of Wakanda University at the American Anthropological Association Meeting in San Jose, California, that November. It was an odd conference year. The air was heavy and thick with toxic smoke from one in a series of many California wildfire crises to hit the state. We were all nervous about the air quality and I wore an N95 mask to the conference, concerned about the impact of the smoke on my latent asthma. Little did I realize that just two years later mask wearing would become a thing of habit and N95s would become a commodity akin to gold. The smoke-filled air gave the conference an eerie apocalyptic feeling as we tried to make normal out of the abnormal reality of climate crisis and uncertainty. The smoke was not the only newcomer to the conference that year, however. Elizabeth Chin, Danya Glabau and the Laboratory of Speculative Ethnology also brought Wakanda University

Dorinne Kondo has spent her anthropological career interrogating the politics of crafting selves and worldmaking through the lens of performance. At the center of her interrogations has been the question of race, and how performance and race are intimately intertwined. Worldmaking: Race Performance and the Work of Creativity is a continuation of these reflections and inquiries, this time focusing squarely on the theater as a space of race making, world making, creating and iteration. Here, Kondo engages with the theater unabashedly; thinking critically about how race becomes a site of sociocultural negotiation and contestation not only through the act of staged performance but also through the hidden and out-of-sight ways that race is negotiated through the business of theater: its profit margins, its contextualization, and its delicate dance between pleasing the audiences that typically consume the theater and challenging the hegemonic narratives of race that make those audiences laugh, cry, and consume the stage. Kondo’s close relationships with world-renowned playwrights Anna Deveare Smith and David Henry Hwang take center stage in this text as she explores the racial economies of the theater, racial affect, and the anthropology of performance. In this sense, the book is both an exploration of the theater as an ethnographic site of race making and also Kondo’s auto-ethnographic reflection on her work in the theater as a dramaturg and playwright since the 1990s. Crucial to the auto-ethnographic element of the book is the Kondo’s inclusion of the full script of her play, Seamless.

SeamlessIt is the material manifestation of Kondo’s critiques and interventions in Worldmaking—her creative/theoretical intervention in response to her critiques, so to speak. Kondo describes playwriting as “reparative creativity” (209). As she observes, “notions of racial melancholia, show us that the past can never be over in any simple sense; losses are introjected, becoming constituitive elements of the subjectivities of the living . . . our subjectivities are the graveyards of our losses, which never disappear” (210). Racial performance, in this sense, is a haunting.

With Seamless, Kondo hopes to create new ways of being, knowing and representing the Japanese American experience not through stereotype and affective violence (a topic that she eloquently deconstructs in throughout the book), but rather through storytelling that “talks back” to social constructions of race/gender/sexuality/class that often flatten out rather than complexify the multidimensions of race and life. Kondo writes, “Seamless stages the gendered, racialized effects of historical trauma in the aftermath of global conflict” (210). What does it mean to confront our past as a process of identity formation? What role does historical trauma play in defining our racial subjectivities both individually and collectively, and what role does telling these stories play in our collective healing and worldmaking? At the heart of these questions is the relationship between racial trauma and subject formation. Affect sits at the crossroads of this conversation. The theory of racial affect becomes a tool for thinking through trauma as a productive (not positive or inspiring but worldmaking) site of contestation. It is where and how we learn how race fits on our bodies and in our minds. It is the struggle that we have between our individual selves and our collective selves as racial subjects. It is worldmaking in that makes us as subjects and also makes our social world. It is the site of internal and external struggle and it is, in this sense, also a familiar juncture where racial meaning materializes.

Enter Seamless stage left. San Jose.

As we entered the rotunda of the convention center, a familiar sense of apprehension set in—what business does the anthropologist who observes theater have in doing theater herself? No matter how many times I venture onto the stage, I still find myself asking this question, wondering if I am worthy to be under the lights. Yet, Dorinne Kondo continuously pushes us to disrupt this false binary between researcher and performer by reminding us of the place that the theater plays in defining our social and epistemological world. Indeed, only an invitation from her could have convinced me to push outside of my comfort zone to perform in front of my colleagues at the AAA meeting. It is not every day that someone whose work we admire profoundly trusts us enough to represent their vision to the world. I pushed my nervousness to the side and slipped into my performer-self (the one I tend not to share with my academic colleagues, the woman who has performed on stage for much of her life but hides this self from the world for fear of becoming labeled as a scholar who is not rigorous enough). Yet in my discomfort, I also, unexpectedly, found a sense of freedom: me the anthropologist as creative, playful, and theatrical. The only way to defeat the devil is to embrace her, otherwise she never goes away.

KATHLEEN unsheathes a sword with her free hand

and executes dazzling sword play.

I lunged forward into the dual, clacking my imaginary sword together with my nemesis, Diane. The rotunda became an office space and also a material and symbolic site of struggle. As Kathleen, I was the devil challenging Diane to remember her past, the haunting of identity and racial trauma. Yet, as Kathleen I was also sparring with my own anthropological persona; working against the voices that have told me that performance and anthropology can only mix theoretically and not in practice in our anthropological lives. I let myself slip into the performance and in so doing I not only embodied Kathleen but all that she represents as the devil on our shoulder reminding us of the ghosts that haunt our past and present and make us who we are as gendered racial selves (I, a Black woman) and as complex scholar-subjects who can never real be the pure intellectual subject the discipline begs of us.

When we as anthropologists engage in the theater, we not only merge performance and ethnography but we also tap into a perspective of the world—a process of creativity, to paraphrase Kondo—that is its own methodological and epistemic frame. Performance is not just a lens into our social world, it is worldmaking itself, that which produces and creates the imaginaries that define our social and cultural universe. Worldmaking provokes us to recall this creationary power of the theater by thinking about the relationship between theater, performance, race and creativity, not from an abstract and distant perspective but rather from her perspective as an experienced dramaturge and playwright.

Where can an anthropology of the theater take us? In what ways can it be reparative and also “count as serious scholarship and as theory”? In my own work, I argue that performance can be the theoretical and metaphorical lens through which we can refract our everyday reality just enough that we can begin to perceive the nuances of race making and worldmaking that otherwise go unnoticed because they have become too familiar: like the choreography of police violence and the scenario of antiblack state-making. Yet, what Kondo reminds us of is the need to take our engagement with performance, ethnography, theater and anthropology beyond the metaphorical and symbolic realms into the creative and performatic: real theater so to speak. Creative play—from sword fighting to theatrical storytelling—is an imaginative reflection on how we make and create the world and also an epistemological refraction of the world that allows us to see its contours and dimensions in ways that we cannot through our normative tools of anthropological storytelling (ethnography, anthropological theory, scholarly prose). In this way performance is theoretical practice that produces privileged and nuanced insight. It is scholarly and not just creative. It is theoretical and not just reflective. It is worldmaking.

See https://wakandaaaa.home.blog/about-wakanda-aaa/.↩

The photograph features a dress my mother sewed for me, one of a trio of backless halter dresses in bright, “tropical” prints that I took to college. From seventh grade, I was enraptured by clothes and fashion, fostered by a visit to my LA relatives that year. The Hollywood Bowl! The Beatles at Dodger Stadium! The beach! Stylish outfits! Things I had never experienced in my small, Eastern Oregon town, a desolate, high plains desert I then longed to escape. (Now I find it fascinating, given the snobbery of the academy, the relative marginalization of the rural in cultural theory, and the mix of settler colonial populations, from WASPy whites to Basque descendants of sheepherders to a Japanese American population resulting from internment diaspora.) I spent hours drawing versions of fashionable ensembles from the teen magazine Seventeen, drawing women’s eyes (yes, double-lidded—both my mom and I have double lids naturally), makeup, hairstyles. Fashion signified a link to a larger world.

The photograph features a dress my mother sewed for me, one of a trio of backless halter dresses in bright, “tropical” prints that I took to college. From seventh grade, I was enraptured by clothes and fashion, fostered by a visit to my LA relatives that year. The Hollywood Bowl! The Beatles at Dodger Stadium! The beach! Stylish outfits! Things I had never experienced in my small, Eastern Oregon town, a desolate, high plains desert I then longed to escape. (Now I find it fascinating, given the snobbery of the academy, the relative marginalization of the rural in cultural theory, and the mix of settler colonial populations, from WASPy whites to Basque descendants of sheepherders to a Japanese American population resulting from internment diaspora.) I spent hours drawing versions of fashionable ensembles from the teen magazine Seventeen, drawing women’s eyes (yes, double-lidded—both my mom and I have double lids naturally), makeup, hairstyles. Fashion signified a link to a larger world. The photo of my mother was taken when she and my father were dating. She was in her early thirties. Note the carefully waved hair, the perfectly arched eyebrows (that remained perfect throughout her life), the red lipstick. During the 1960s, she adopted black eyeliner to rim her upper lids, a makeup practice I adopted as an adolescent and have never abandoned, even when it was unfashionable. I feel unfinished without it. When I write, I prefer to look “professional,” even when I am alone. Is this, like my black eyeliner, a maternal legacy?

The photo of my mother was taken when she and my father were dating. She was in her early thirties. Note the carefully waved hair, the perfectly arched eyebrows (that remained perfect throughout her life), the red lipstick. During the 1960s, she adopted black eyeliner to rim her upper lids, a makeup practice I adopted as an adolescent and have never abandoned, even when it was unfashionable. I feel unfinished without it. When I write, I prefer to look “professional,” even when I am alone. Is this, like my black eyeliner, a maternal legacy?

Lana Lin

Response

Seams

Characters

LL—Taiwanese American filmmaker, artist, writer

DK—Japanese American anthropologist, dramaturg, playwright

ADS—African American actor, performer, playwright

MK—Jewish Austrian psychoanalyst

DWW—White British pediatrician and psychoanalyst

JW—White Rhode Island professor of English

OAO—White Danish psychoanalyst

EKS—Jewish American poet, artist, literary critic, teacher

DHH—Chinese American playwright, librettist, screenwriter

TN—African American cultural critic and scholar

SA—Australian, British Pakistani feminist writer, independent scholar

AL—Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet

RWG—Black prison abolitionist and scholar

TIME—Spring 2021

PLACE—Online

ACT 1

(The empty space behind the characters is filled with a painting of a life-sized woman, half sitting, half lying, her skin like gold.)

LL: When I was a child, I enjoyed watching the television series Kung Fu, often with my father. Neither of us ever commented upon the fact that the main character, a half-Asian Shaolin monk, was played by non-Asian David Carradine. There was nothing out of the ordinary in this, so conditioned was I to unmarked whiteness standing in as the universal. I had no critique about racial masquerade and no expectation of seeing myself reflected on screen. One could dismiss this as a child’s lack of knowledge, but surely if the world of representation actually reflected the real world, a child could cognitively assess the difference between a white person and a person of Asian descent. The fact that I was trained not to see or even to expect the world of representation to mirror my own is really rather tragic, not something given.

LL and DK: The world of representation is made not given. Who is on screen matters.

DK: Who is standing onstage matters. It may be the first step in confronting the unbearable whiteness of mainstream theater.

LL: And the unbearable whiteness of media.

LL and DK: Who is behind the scenes also matters.

DK: The team of dramaturgs for Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight were unified in a common goal, not in our similarities. We fought, we were brought to tears, but this discomfort, the hard work of adjudicating passionately held, sometimes incommensurable positions, characterized our politics of affiliation.

ADS: She has been known to make me cry.

LL: A Japanese American woman who can make an African American woman cry—that’s impressive.

DK: Dramaturgical critique is a mode of political intervention and a form of reparative creativity.

LL: (To DK.) What you call “reparative creativity” I have referred to as “creative reparative” projects and objects. (To MK.) You taught me that mourning is reparative work. Speech, care, reading, writing, love—these are all or can be reparative performances.

(A video of an infant suckling is projected on top of the painting.)

MK: Let me remind you that the first creation in the mind of the infant is the maternal breast.

DWW: And the baby’s capacity to love emerges from this creativity.

DK: (To MK.) I have been wondering about this painting behind us

MK: Ah, yes, the naked Negress. This was the first painting of a beautiful, wealthy depressive, Ruth Kjär. Evocative, but I was more concerned with the portraits that followed. To be honest my interest was focused on the creative impulse to re-make that which we psychically destroy.

DK: But it is quite disappointing that you skip over analysis of the power-laden valences of this racialized and gendered image.

JW: And you affirm the art historical valorization of the “nude” when you describe the negress as “naked.” The nude is not specifically “raced,” and is presumed to be white. But to paint an unclothed black woman is to paint a “naked, sexualized” woman.

OAO: I spent years tracking down this mysterious painting. It turns out Kjär is a pseudonym. I’m 98% certain that the artist was Ruth Weber who was said “to incarnate the unbearable lightness of being itself” with “a few spatterings of black African blood.” And the painted figure is none other than Josephine Baker!

JW: As I suspected, the artist felt an identification with racial blackness!

DK: In David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face, a white man gets to play a Chinese man. We could say that the play enacts a double layer of cross racial identification, an Asian man identifying with a white man identifying as a Chinese man.

EKS: With a fat woman’s defiance, I identify as a gay man, but the whiteness of my cross gender identification remains unmarked. Is cross gender identification less fraught than cross racial identification?

LL: In my earliest experiences of group dynamics, I would often find myself sitting in a room full of white children with perhaps one other Asian person besides myself, a boy. The presumption that I was a girl gave me a modicum of belonging on the basis of sex whereas my racial status isolated me and made me vulnerable in an ocean of suburban whiteness.

ADS and DHH:

Talking frankly about race can be more intimate than sex!

LL: Returning to the concept of reparation with its multi-layered artistic, psychic, political, legal, and economic meanings . . .

DK: Individuals incarcerated in the Japanese internment camps received $20,000 in reparations through the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

LL: On March 22 this year, Evanston, Illinois, a little over an hour away from the suburb where I grew up, approved reparations for Black residents for codified discrimination, awarding $25,000 to eligible individuals toward housing costs. This is cause for celebration, yet it bears noting that in thirty-three years, the amount of individual reparation has increased only $5,000. And Japanese internment camps operated for four years, while chattel slavery was legal in the US for 244 years.

TN: Racial inertia works to keep the status quo in place.

DK: The metaphor of “repair” resonates powerfully because it acknowledges a savage tearing asunder, after which nothing is ever fully restored.

LL: More than a metaphor, repair is a material process, whether in craft or medical interventions. Creative reparative responses to illness do reparative work. Responses to loss, they attempt to close a gap that cannot be closed but may be at least temporarily bridged.

DK: Our subjectivities are the graveyards of our losses, which never disappear.

ADS: I want the audience to experience the gap, because I know if they experience the gap, they will appreciate my reach for the other. This reach is what moves them, not a mush of me and the other, not a presumption that I can play everything and everybody, but more a desire to reach for something that is very clearly not me—my deep feeling of my separateness from everything, not my ability to pass for everything.

DK: Though we cannot become another, we can leap toward another.

ADS: We can listen for someone’s poem.

DK: But the failures of seamless reproduction—stuttering, tics, rhythmic shifts—can be the sites of political possibility and individual agency.

ADS: Noticing the knots, makings the seams visible.

LL: This goes to how genre and form are related to race-making. Are questions of race in artistic creation always also a question of form? This conversation, for instance, has no dramatic arc, and is almost entirely made up of citation and appropriation.

SA: Citation is feminist memory.

DK: We are constantly engaged in a dynamic of appropriation on a daily basis. Essentialist notions of identity are always already citations of cultural ideals and narrative conventions. Conventional genres assume a universal audience, which is itself a power-evasive move that masks the always already marked character of diverse and incommensurable audiences-in-the-plural, who are unevenly positioned in multiple matrices of power.

(The “naked Negress” painting has disappeared and is replaced by an image of Yong Soon Min’s installation, Movement, which consists of vinyl records, compact discs, mirrors, and paint that form a pattern like a planetary constellation.)

DK: Let us remember not to tether the reparative exclusively to the individual. We need to link the reparative creativity of artistic production to systemic inequalities.

AL: This has been at the forefront of my work as a Black lesbian mother, warrior, poet, which I consider a continuum of women’s work, of reclaiming this earth and our power. Without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression.

DK: (Crosses stage.) If (racial) trauma has an afterlife—if structural racism persists in the very constitution of the subject, whether majoritarian or minoritarian—the postracial becomes an impossibility.

LL: We have never been postracial. The murder of six Asian women in Atlanta on March 16 this year and the never-ending barrage of reports of anti-Asian violence show all too clearly how far from color blindness this country remains. What kind of impact did the Atlanta shootings have on you?

DK: (Chokes, cannot speak, choking on history.)

LL: Let me turn to an anecdote to lighten the mood. Or maybe not lighten it; after all, we’re still in the midst of a pandemic. Since I began with an anecdote, I’ll end with one, and we’ll call it a dramatic arc. In mid-July of last year, a little over six weeks after the killing of George Floyd, I received an email from a white male colleague asking if I might be willing to share links to a few of my short films for his class. He only had the budget to rent one 16mm film print and the rental was earmarked for a white man’s film. Today, less than two weeks since the Atlanta spa shootings, and just over a year since the murder of Breonna Taylor, I received an email from a different white man inviting me to participate on a panel with a white woman and a white man. He confessed that there was only one honorarium and it would go to the person whose income stream was least predictable, which was by his account the white man, who presumably does not hold a university position. These messages frame the past year for me, from lockdown to escalating anti-Asian violence, from the relentless brutality against Black poor lives to the ways in which Covid mortality can itself be seen as a form of racism . . .

RWG: (Somber tone.) Racism is vulnerability to premature death.

DK: Given the power-laden context of affective violence, in which minoritarian subjects repeatedly confront erasure or denigration, reparative creativity becomes a way to give public life to the erased and marginalized.

(Music from the LPs and CDs of Movement rises.)

LL: This is perhaps why I am publicly reflecting on what I would typically keep private. The men who committed these micro aggressions are not Republicans or people who have not benefited from progressive education. On the contrary, they are intelligent Leftists who can critically discuss the problems of settler colonialism, neoliberal capitalism, and the carceral state. They may devote their professional lives to the pursuit of a just, egalitarian, humane and ethical society, yet this vision is suspended in the realm of ideas that may be overlooked in a flurry of email writing. For the rest of us who cannot escape the ways in which our bodies and minds are marked by race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and various states of ability, and age—these identity markers have . . .

DK: life determining impact. Issues of race and class are pervasive and have life-determining impact.

LL and DK: Our redressive outrage can and should be channeled toward world-making that can bear the weight of our marked flesh. (Music cuts out. Blackout.)

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Klein, Melanie. “Infantile Anxiety-Situations Reflected in a Work of Art and in the Creative Impulse.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis 10 (1929): 436–43.

Kondo, Dorinne. Worldmaking: Race, Performance, and the Work of Creativity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Lin, Lana. Freud’s Jaw and Other Lost Objects: Fractured Subjectivity in the Face of Cancer. New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. Argyle, NY: Spinsters, Ink, 1980.

Nyong’o, Tavia. The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance, and the Ruses of Memory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Olsen, Ole Andkjaer. “Depression and Reparation as Themes in Melanie Klein’s Analysis of the Painter Ruth Weber.” Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review 27 (2004): 34–42.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “White Glasses.” In Tendencies, 252–66. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

Walton, Jean. Fair Sex, Savage Dreams: Race, Psychoanalysis, Sexual Difference. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Winnicott, D. W. Playing and Reality. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

6.27.22 | Dorinne Kondo

Reply

Reparation, Creativity, and “the Sadism of a Hostile World”

Lights rise on an image of Yong Soon Min’s installation “Movement,” the cover image for Kondo’s Worldmaking. The (painstakingly chosen) font slowly emerges on the image. DK enters. She brandishes a piece of chalk and traces a rectangular shape on the floor. She examines the shape, turns around to appraise the image of her book. She turns back to the audience, looking quizzical, cocks her head, apparently not quite satisfied.

Slowly, the image of Worldmaking morphs into an image of Lana Lin’s Freud’s Jaw and Other Lost Objects: Fractured Subjectivity in the Face of Cancer. DK gazes at it, touches it, trying to feel its dimensions, trying to develop a haptic sense of its contents. The book opens. We see a page, then another. DK touches the upstage screen, “turning” them feverishly.

DK: Oh my God!

She turns to the chalk outlines of the rectangle she has drawn, takes up the chalk, starts writing. Suddenly a golden light illuminates the space of the book outlined on the floor. The sky opens, and fragments of pages waft down from the ceiling. DK watches in wonder. As the fragments float earthward, she gathers handfuls of paper, first tasting them, then stuffing them into her mouth. Devouring.

LL: You might hurt yourself. Eating so fast.

DK: (muffled, her mouth is stuffed) Making up for lost time.

LL: The oral phase in Klein involves fusion. Aggression Guilt for the aggression.

DK: I love this book! And I feel guilty that I didn’t know about it before.

LL: It would have been nice. How did we not know each other’s work?

DK: I don’t know. I don’t know! I feel like a deficient academic.

LL: Maybe it’s the academic hiving.

DK: Our silos. Film and performance are different.

LL: But not.

DK and LL. That different!

DK: And I feel such affinity. Resonances, moments of “fusion” and a realization of separateness.

LL: Klein. What I called the creative reparative.

DK: What I called reparative creativity.

LL and DK: We both believe in the power of the arts, of work, of writing, of objects, of making, as reparative practices.

DK: As you said about Audre Lorde:

LL: “She mobilizes the oscillation between destruction and creation, between death and life, putting death to use such that survival amounts to an insistence upon ‘not death.’ She does not try to imagine a world without pain and hardship. She tries to imagine a world that can make use of it. She tasked herself to create something new, something that did not seek to restore the past or fill the absences that remained in the wake of devastation.” In the face of bodily vulnerability. Existential vulnerability. Mine, breast cancer. In remission, that aberration of linear temporality.

DK: Mine, open heart surgery that left me at best two-thirds of who I was before. Never completely healed or back to normal. Feeling much worse than before the surgery. Despite numbers and metrics that say I am back to “normal.” But what about my daily violent fatigue?

LL: I talk about Lorde and her difference from Klein.

DK: It’s so important! I want to amplify this point in my next project on fear and its unequal distribution. For me, as a cis-gender Asian American woman, this is the first time—at least in Los Angeles—that I’ve felt such palpable fear of being physically attacked. I’ve been “used to” verbal assault for decades. The worst was New Haven in the late ’80s or early ’90s. Three in twenty minutes. But racial harassment happened regularly in Boston. Only once in LA, even after all these years. Visual, not verbal. Young kids stretching the corners of their eyes into a slant. Microaggressions are another story, of course. So . . . what about populations who live constantly with fear . . . of death, deportation, who cannot sleep safely in their own beds, if they even have one? Some populations are more “vulnerable to premature death,” as Ruthie Gilmore would say, than others. As COVID, racist, gendered, anti-trans violence dramatically underlines. You said so eloquently:

LL: “For Lorde the offenses of sexism and racism converge in their demand to cover over differences that are apprehended as transgressive . . . she recognized that the convergence of multiple registers of identity constructed her and her sisters of color as especially vulnerable to violences of all sorts, including but certainly not limited to ill health, poverty, sexual assault, and discrimination. . . . One could say that the poisonous projections of hatred, which Lorde experienced as a black lesbian, produced what Klein called schizoid defense mechanisms in which parts of the self are annihilated. . . . Klein’s theories on aggression . . . describe it in terms of injury and a threat to survival. But for both Lorde and Klein, aggression can also be self-protective . . . importantly, Lorde’s masochism responds to a sadism that, unlike Klein’s phantasied aggression extends from the reality of a hostile world. “

DK and LL: A SADISM THAT EXTENDS FROM THE REALITY OF A HOSTILE WORLD.

DK: Fear and aggression, not as phobia or as excessive, but a reasonable response to that world.

LL: The creative reparative.

DK: The creative reparative.

LL: The work of creativity.

DK: Reparative creativity.

LL: Fractures.

DK: Fragments.

LL: Moments of joy.

DK: And passion.

LL and DK: And survival. Remaking worlds. But never completely.

They each take a broom and sweep off the chalk. KUROGO carry in a rounded, transparent dome, lopsided and in disrepair. Some panels are torn. A snow globe, perhaps, that LL described eloquently in Freud’s Jaw? LL and DK step inside to inspect. Small, white paper fragments drift down from above, like snowflakes. They enjoy the falling snow for a moment, then start their work of repair, gathering the snowflakes into piles, trying to patch the panels of the globe, as snow continues to fall and lights fade.

Chloe Johnston and James Moreno, “Illuminations/Marginalia,” master’s thesis, Northwestern University, 2007. On a visit to Northwestern’s Department of Performance Studies, I was invited by E. Patrick Johnson and D. Soyini Madison to the rehearsal for an MA thesis production devised by two of their students. Even in rehearsal, “Illuminations/ Marginalia” remains one of the most memorable theatrical experiences I’ve had—epitomized in a scene where a woman gazes in wonder at the light illuminating a book, the falling fragments of paper falling from the sky, and literally devours the pages. Is there a more telling theatricalization of an intellectual’s relation to the book? “Making words flesh,” as the authors say?↩