Symposium Introduction

Here is a story perpetually made new: that literary modernism constitutes an aesthetics of shock. From the onslaught of the city, to the perceptual shifts wrought by new technologies, to the disorienting chaos of war, modernism—in this perennial narrative—mediates the psychological wreckage of global modernity, abstracting its eruptive force into stylized literary experiments. Not least as a means of cushioning the blow. As Walter Benjamin argued in his 1939 essay, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” at the heart of the modernist lyric may be the “shock defense,” a way of parrying psychic disturbances by transmuting them into self-contained poetic moments. Rooted in the Freudian insight that preparedness for shock dulls its perception, Benjamin’s essay places trauma and its mitigation at the center of modernist practice. While modernists aimed for formal and perceptual innovation, modernist historiography largely suggests that they did so by preparing not to be shocked, channeling experiential assault into controlled forms of destruction.

Yet as Kate Stanley’s Practices of Surprise in American Literature After Emerson elegantly contends, this narrative of modernism has obscured the important ways in which modernists actively and creatively cultivated the unforeseen—in its most positive valences—as central to their compositional praxis. Against the critical tendency to read modernism’s destabilizing experiments as a monolithic response to the experience of modernity as trauma, Stanley maps out a counter-tradition of modernism emanating from Emersonian pragmatism, a mode of generative indeterminacy and “structured openness” to the world. For Baudelaire himself, as well as for the writers and artists to which Practices of Surprise lovingly attends—Henry James, Marcel Proust, Gertrude Stein, Nella Larsen, and John Cage—Emerson provided a model of creative surrender to the unpredictable currents of experience, and to the transfiguring potential of the fortuitous surprise. Recovering this transatlantic Emersonian legacy, Stanley’s study maps a lineage of modernist practice that inherits and extends Emerson’s emphasis on self-effacing receptivity to the unknown. “The one thing we seek with insatiable desire,” Emerson wrote in his 1841 essay “Circles,” “is to forget ourselves, to be surprised out of our propriety, and to do something without knowing how or why; in short, to draw a new circle.”1 Moving away from the Benjaminian emphasis on shock, Practices of Surprise reminds us of the ways in which modernists desired, embraced, and indeed practiced radical uncertainty, drawing new and more expansive circles at every incalculable turn.

To be surprised in an age of trauma, as modernists well understood (and as they imbibed from Emerson), required sustained and cultivated habits of mind. Shifting the dominant logic of much of the historiography, Stanley’s study centers surprise not as an unlooked-for disturbance—the experience of being buffeted by the contingencies of the world—but as a sudden affective recognition sought and prepared for through an active training of the attention. Modernist surprise, Stanley contends, is a function of disciplined preparation—a mode of reception to the unexpected that careful reading and thinking with others might enable. Through each of her readings, Stanley elucidates pragmatism’s embrace of contingency and “adaptive precariousness” as it served modernism’s broader disruption of conventional aesthetic forms (24). At the same time, she demonstrates how pragmatism comprised (and continues to comprise) a kind of relational ethics, wherein formal and prescriptive dogmas might be tenderly loosened, and through which art might become a collective inhabiting of uncertainty.

Practices of Surprise, in other words, offers surprise as a methodological as well as an ethical and (perhaps most surprisingly) pedagogical imperative. As Kristen Case points out in her essay “Recovering a Pragmatist Pedagogy,” at the heart of Stanley’s study is the enactment of pragmatism as a pedagogical practice, a way of reading and teaching that celebrates creatively honed modes of reception and lively, intersubjective encounters. Asking us to train our attention on this often-overlooked pragmatist pedagogical inheritance—one reiterated and sustained in classrooms but rarely circulated in print—Stanley offers a distinctly alternative critical genealogy, at odds both with the hermeneutics of suspicion and with its various agonists. As Case asks, “What might the discipline of literary studies look like if, rather than hemmed in by a picture of reading as ground zero for the anxiety of influence, it circled around an Emersonian scene of generative reception?” Writing in and about a pragmatist lineage that fundamentally refuses the distinction between criticism and pedagogy—and that foregrounds iterative practice as central to both—Stanley lays out a ground for reading founded not in Oedipal struggle but in mutually transformative acts of recognition and exchange.

This is a fundamentally reparative venture—an effort to recover modernism’s improvisatory spirit, its cultivation of the enlivening surprise over and against (and in the midst of) sense-deadening shock. As each of the essays in this forum take up in different ways, Practices of Surprise both extends and at times usefully destabilizes the “optimistic theodicy” that has haunted pragmatism in the Emersonian strain. While inspiriting precisely the kind of generative openness that Stanley recovers in modernist practice, pragmatism’s sanguinity in the face of radical uncertainty has for many critics made it a difficult language through which to confront structural and institutional forms of violence and constraint. Taking up this abiding tension, Case offers Cornel West’s elaboration of “prophetic pragmatism,” which (in Case’s terms) tempers the “comfortable optimism of white pragmatist thought” with a more straightforward and thorough confrontation with the tragic. Perhaps especially in her reading of the atmospheric turbulence of Nella Larsen’s Quicksand (1928), Stanley signals the limits of pragmatism’s embrace of precarity as a philosophical comportment in the face the very real precarity wrought by structural racism and misogyny. At the same time, in her response to Case, Stanley insists on the “spirit” of pragmatism as an epistemological and pedagogical sanctuary, one where real risks might nevertheless be confronted and shared in the vibrant laboratory of the classroom.

In a similar vein, Mary Esteve asks whether Emersonian pragmatism’s emphasis on ambivalence and endless deferral might have enabled—or even constituted—a falling away from concrete ethical and political commitments in favor of an aesthetics of uncertainty. As Esteve contends, the pedagogical lineage of pragmatism that Stanley elaborates tends to obscure an institutional history that privileged experience at the expense of political belief and actionable intervention. Taking up the centrality of Richard Poirier to Stanley’s own inheritance of pragmatism, and recalling Poirier’s foundational role in the development of Harvard’s Hum 6 course, Esteve points to the way that the institutionalization of pragmatist pedagogy may have helped reify aesthetic detachment and political quietism as norms of academic engagement. At stake in Esteve’s essay and in Stanley’s response are competing understandings of the relationship between pragmatism’s carefully honed modes of perception and liberal democracy’s (at least rhetorical) demand for rational judgment and deliberative action. These understandings emerge through divergent readings of Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04, which interrogates the crisis of global climate change through the entanglements of perception, cognition, and intervention. While Esteve reads the novel as a scathing critique of romantic sublimity in the face of pending global catastrophe, Stanley notes the novel tracks precisely the challenge of integrating rational knowledge of climate change with what it feels like to experience it, contending that the novel’s attention to pedagogy is animated ultimately by a pragmatist ethics of care.

In one of its central moves, Practices of Surprise insists on the paradoxical ways in which surprise is “facilitated by preparation”; surprise, in this model, is a function of rigorously disciplined practices of awareness and attention (4). Yet as Alex Benson suggests, there are different ways to approach the relationship between surprise and discipline, particularly when we expand beyond Emerson to consider other nineteenth-century thinkers of surprise. Reading Frederick Douglass’s Narrative, for example, Benson points to the intimacy between surprise and paranoia; Douglass describes learning to “expect” surprise assaults from the overseer, a kind of disciplined awareness and anticipation necessary for surviving chattel slavery. Echoing Case’s call for tragedy as a potential counterweight to Emerson’s insistence on “optimistic theodicy,” Benson asks, “What does Emersonian surprise look like when what we set it against is not Benjaminian or Freudian shock . . . but rather the moral shocks, the sentimental appeals, of Emerson’s lifetime?” If, as Benson signals, Douglass and other abolitionists aimed for the shocking facts of slavery to be morally instructive, what is gained and lost by a reparative embrace of Emersonian surprise? Taking up this invitation to reexamine Douglass’s own scenes of instruction, and particularly moments of shared reading that constitute the most hopeful moments of his Narrative, Stanley’s response contends that “Douglass’s reparative hope . . . proves to be as much a matter of survival as his paranoid vigilance.” Making room for genuine surprise amidst such compulsory vigilance becomes an important measure of what it means to be free.

Alicia DeSantis takes up the paradox of preparing for surprise in a different vein, arguing that to move beyond the critical context of modernism is to understand such preparation as the most ordinary of experiences. As DeSantis suggests, “the concept of a form of discipline designed to be openly responsive to contingency is not only non-contradictory, it’s in fact familiar—from baseball to baking, ceramics to sex.” DeSantis juxtaposes this more familiar version of paradox with the specificity of literary paradox as the fundamentally unresolvable work of interpretation, and places this latter form at the heart of Emerson’s restlessly oscillatory and often circular metaphors (part of what makes them so challenging for undergraduate readers). In doing so, DeSantis presses on the distinction that Practices of Surprise makes between the kind of rarefied paradox that the New Criticism installed as central to the very definition of the literary object, and the kind of paradoxes that pragmatism embraced as the bridge between literature and everyday experience. New Criticism and pragmatism part ways, Stanley argues, “at precisely the point that the New Critic installs the concept of paradox as a core tenet of close reading,” turning the contingencies of interpretation into “a preformulated program and a prescribed procedure” (40). As both DeSantis’s essay and Stanley’s response suggest, the pragmatist paradox becomes valuable insofar as it exceeds the self-enclosed system of critique to become “a program for more work.” Or as Stanley puts it, “whether Emersonian paradox opens up or shuts down new paths for thinking depends on whether our ‘interpretive oscillation’ ultimately moves beyond itself.”

The question of how pragmatism moves in and beyond paradox into collective action—indeed into something like mutual care—is perhaps the abiding concern in each of these essays, as it is in Stanley’s book. In the forum’s final essay, Lisi Schoenbach describes a divide within pragmatist thought between “problem solvers” and “paradoxical thinkers.” As Schoenbach suggests, problems solvers (embodied by John Dewey and Richard Rorty) approach pragmatism as a set of conceptual tools and values meant precisely to intervene in the endless deferral of decisive action as Esteve describes it, while paradoxical thinkers (including Emerson, Richard Poirier, and many of the figures on which Practices of Surprise dwells) embrace pragmatism as a mode of expression—a poetics of uncertainty. Pragmatist poetics offers a rich language for the affective experience of the revelatory surprise, and thus for the embodied and concrete ways in which language mediates a world of uncertainty. Yet as Schoenbach argues, “individual wonderment, reflection, and personal transformation (the key elements of the paradoxical approach to pragmatism) do not begin to address collective and institutional change across time, social experience, or the social world.” Schoenbach suggests we approach these divergent pragmatist traditions as complementary rather than oppositional; as she points out, for many of the thinkers who people Stanley’s book, artistic experimentation and collective action were deeply interwoven practices.

As Stanley’s response to Schoenbach underlines, what may surprise us most about paradox-minded pragmatism is its emphasis on collaborative world-building as uncertain, risk-filled, and absolutely necessary work. Returning us to William James’s account of pragmatism as “a social scheme of co-operative work genuinely to be done,” Stanley signals how a pragmatist genealogy of modernism may help us better see the relation between the project of following experimental composition to its unexpected, often surprising ends, and the necessarily improvisatory (if no less disciplined) work of social change and collective care. In an era of endlessly shared but unevenly distributed trauma, in which the iterations of state violence and social collapse evince the Benjaminian state of emergency as the very rule by which we live, Practices of Surprise helps us recover the transformative labor of surprise—labor in which the ends are not given, and are thereby not assured. Which is what makes Stanley’s emphasis on the classroom an instructive one; for it is there, she suggests, where practice opens onto new and surprising modes of relation, and where any truly reparative project might wish to begin.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures (New York: Library of America, 1983), 414.↩

1.27.21 |

Response

Emersonian Intimations and Pedagogy

Who doesn’t like surprises? Unless modified by an unfavorable term like unpleasant, nasty, or cruel, the connotative tilt of surprise is toward the propitious. Still, there are some people who embrace surprise more than others, who indeed fathom its profounder intensities and cultivate conditions of mind and circumstance to receive its challenges. For the practitioners of surprise populating Kate Stanley’s eloquent and learned monograph, the experience of surprise possesses the force of a raison d’être. To be clear, these practitioners are not the experience-mongers of today—not the Anthony Bourdains or Sanjay Guptas trotting around the globe for the benefit of television viewers’ vicarious consumption. Rather, they are modernity’s formidable thinkers and artists: freelance essayist-lecturers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Cage who enjoin everyday defamiliarization; modernist writers such as Marcel Proust, Henry James, Nella Larsen, and Gertrude Stein who compose situational and verbal dramas of unexpectedness; pedagogues such as John Dewey and Richard Poirier who develop educational philosophies and curricula that foster learning via experiential disorientation; and scholar-critics such as Philip Fisher, Christopher Miller, and Stanley herself who locate, describe, probe, and largely encourage surprise as a cognitive and perceptual experience.

Stanley is particularly interested in the way Emersonian surprise worms its way into and flourishes in the writing practices of prominent modernists. As they disclose ways of being receptive to disorientation, self-effacement, and seeing the world anew, what shapes these modernists into a group is not only their attunement to surprise, but their immunity to shock. One of the key aspects of Stanley’s book is its argument against historical materialists who have converted Walter Benjamin’s provisional account of shock modernity into totalizing doxa. Such critics thereby reduce modern subjectivity to a defensive crouch, fixated as they are on delineating the everyday bombardments of urbanization, industrial mechanization, capitalist alienation, gender and race dysphoria, colonization, and war. As Stanley persuasively argues, this critical approach winds up “normaliz[ing] shock as the sole variety of experiential suddenness, consolidating a diversity of encounters into a single, and reductively negative, affect” (13). By contrast, Stanley looks to modernism’s pragmatist genealogy, rooted in Emerson’s lebensphilosophie of revelation through disciplined introspection, to recuperate what she calls “a countervailing optic for regarding life as a ‘series of surprises’ unfolding from within, in whatever place and whichever time one’s experience occurs” (13). Despite the polemical confrontation here, these are not so much fighting words as reparative ones. If Stanley’s book is marked everywhere by critical acumen, it also delivers its insights with exceptional geniality.

What follows from Stanley’s reclamation of surprise is twofold. First, she develops her own surprising—at times dazzling—accounts of modernist texts that effectively reinvent the surprise encounter. Chapters on Proust, Henry James, Larsen, and Stein reveal these authors’ idiosyncratic ways of narrating “radical interruptions of expectation at the levels of readerly perception, literary syntax, and formal coherence” (148). James, for instance, over his long career moves away from hardened oppositions between the naïve American sensibility and the European disillusioned sensibility, opting instead to explore more complex interpersonal relations, as well as to embark on more convoluted syntactic adventures that betoken a productive willingness to be surprised by disorientation and to descend into self-erasure. Regarding Larsen’s novel, Quicksand, Stanley makes a fascinating case for the correlation between the main character’s inner volatility and the narrative’s figuration of meteorological atmosphere, particularly of clouds and storms. This correlation becomes the novel’s way of breaking out of the antagonistic logic of double-consciousness made famous by W. E. B. Du Bois and replacing it with a less predictable, less oppositional, and decidedly more Emersonian mode of double-consciousness. The close, patient, and erudite analyses performed in these chapters bring literary-historical specificity and heft to Stanley’s claims about modernism’s debt to the disciplined practice of experiencing surprise.

Second, Stanley’s book expresses a commitment to the integration of Emersonian surprise into contemporary pedagogical practice. While an ancillary concern of the book, this intriguing proposition gains visibility in the book’s introduction and coda, thus inviting our further consideration. In her introduction Stanley describes an extension of chain-linked pragmatist mentors and tutors over generations: from Emerson to William (and, consequently, Henry) James, thence to John Dewey, Gertrude Stein, and Robert Frost, thence to midcentury teachers and scholars, and finally to Stanley’s present-day mentors, such as Joan Richardson and Ross Posnock. On the one hand, this narrative of torch-passing adds individuating warmth to a centuries-long history. On the other hand, its personalism obscures somewhat the role academic institutions have played in the making of a pedagogical tradition. To be sure, Stanley mentions the centrality of Harvard during the James era as well as later in the mid-twentieth century when, alongside Amherst, it developed general education courses that were informed by pragmatist methods. Similarly, the coda’s discussion of John Cage’s practices of surprise nods to his time at Black Mountain College, where pedagogical experimentation drew on Dewey’s ideas of experiential education.

By and large, however, Stanley understands pragmatist pedagogy as an individuated enterprise, where the chain of transmission is sustained through a process of self-selection. This perspective shapes, for instance, her illuminating discussion of the important critic and teacher Richard Poirier, who is usually overshadowed in the discourse of pragmatism by more prominent figures of his generation, such as Richard Rorty and Stanley Cavell. In the 1950s Poirier participated as an instructor in the development of “Hum 6” at Harvard, the experimental general education course in reading and interpreting literature that proved central, as Stanley explains, to combatting New Criticism’s restrictive agenda (38–40). While informative as far as it goes, Stanley’s focus on Poirier’s intramural opponents in New Criticism forecloses attention to the broader implications of pragmatist experimentalism itself, and steers her toward credulous approval of Poirier’s defense of literary pragmatism’s political inefficacy. She notes (quoting Poirier) that “where scholars ‘might possibly begin to help change existing realities’ is in their capacity as teachers and mentors. If there’s any ‘social or communal efficacy’ in scholarly work, it’s modestly limited to making room, in class and on the page, for quiet forms of reflection Emerson calls action” (46). One has reason to wonder if both Poirier and Stanley doth demur too much. While they are quite right not to confuse literary studies—or, more to Stanley’s point, an aesthetic practice of surprise—with political action, the question remains as to whether the institutional adoption of these new pedagogical methods was a good thing for undergraduates. It is worth keeping in mind that Hum 6 was a general education course, not a seminar for self-selecting graduate students.

For a more skeptical view of Poirier’s (and his teacher Reuben Brower’s) curricular instruction, we can turn to Michael Trask’s recent book Camp Sites: Sex, Politics, and Academic Style in Postwar America (2013), which examines pragmatist experimentalism in the broad context of postwar school culture.1 If the end of World War II ushered in heightened US defensiveness in the form of an obsessive national security state—in keeping with the shock-and awe-strategy of atomic warfare—it also gave rise, as Trask tells it, to a new academic “style,” adopted by university intellectuals across the disciplines. With this term Trask denotes “manifestations of conduct and attitude,” or what Bourdieu calls “‘dispositions,’ from gestures to norms of interaction, that a social group both forcefully and unknowingly reproduces” (Trask, Camp Sites, 21). At midcentury, the style in ascendance entailed privileging experience at the expense of belief. It encouraged ironic detachment or, in pragmatist parlance, an anti-foundationalist and quintessentially Emersonian sense of being both inside and outside oneself. In turn, this style contributed to the atrophy of doctrinal beliefs and commitments, including the liberal principles and values that leveraged progressive activism (such as combatting injustice, poverty, inequality, and so forth).

Trask zeroes in on Harvard’s Hum 6 and Amherst’s English 1 as examples of school culture’s misguided abandonment of belief. He details their emphasis on new experience and “productive disorientation” (59), pointing to assignments and curricular techniques that (quoting Poirier) “aimed ‘to practice the art of not arriving’” anywhere specific but instead allowed students “to carry on the ‘acutely meditative process’ of indefinite if not indefinable reading” (58). Citing Dewey’s influence on this Emersonian project of self-renewal and transformation, Trask argues that pragmatist ideology tended “both [to] overrate and trivialize experience” (63). With pedagogy organized around the pursuit of new experience, alongside the instruction both to inhabit and distance oneself from new experiences, the value of any specific experience—indeed, the very framework for measuring the value of experience—risked melting into air. While Poirier may have insisted on the distinction between literary pragmatism and political agency, Trask discloses how institutional pragmatism “paved the way for a politics of the noncommittal” (59). Similarly, where Stanley looks to pragmatist practices of surprise for a way “to close the gap between art and life” (29), Trask shows that such a program might well collapse life into an aesthetic state of aloof disorientation. Where Stanley forges a pedagogical “ethics” out of “surprise’s capacity for activating and enriching states of uncertainty, ambivalence, or repetition” (26), Trask contends that pedagogical preoccupation with the self’s potentialities threatens to displace liberal ethics altogether: “What recedes from view is a political framework grounded on ethics, on the appeal to what a democracy ought to be, what normative aims it should have, and what qualities might guarantee or advance those aims” (Trask, Camp Sites, 4).

However much at odds, Stanley’s and Trask’s work on modernism and midcentury culture proves acutely relevant to our contemporary moment. By way of conclusion, I want briefly to turn a highly acclaimed recent novel whose protagonist crystallizes the knotty predicament of being almost as divided as Stanley and Trask are from each other. The narrator of Ben Lerner’s autofictional narrative, 10:04 (2014), is a devotee of Emerson’s foremost heir, Walt Whitman.2 Meditations on his fellow Brooklynite poet are liable to overtake—i.e., sur-prise—him to the point of intense disorientation, of feeling “a fullness indistinguishable from being emptied” (Lerner, 10:04, 109). He is also heir, as are we all, to twenty-first-century effects of climate change—specifically in his case, Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy, which respectively open and close the narrative. Fixated on storm surge and the prospect of being underwater, Ben repeatedly makes reference to octopuses, whose limited proprioception he explicitly, indeed swimmingly, identifies with. While a pleasing figure of disorientation and uncertainty, the creature is also subject to high-end culinary consumption, once it has undergone a kind of prolonged surprise/shock treatment of being “massaged gently but relentlessly with unrefined salt” five hundred times, and to death (153). Its human counterpart, Ben, thus emerges as an open-armed or tentacled recipient of the Emersonian spirit who is also tenderized by both slow-motion and puncturing surprises of climate-change disaster. He can’t be reduced to defensiveness against modernity’s shock conditions, but he also can’t fully ward them off.

More to the point of cognitive and perceptual experience, the octopus is but one figure among many employed by Lerner to gesture toward the hazards of embracing aesthetic experience as a way of life, insofar as this disposition entails relinquishing the kind of rational, integrative understanding needed to picture, develop, and live according to sane environmental policy. It turns out, however, that, besides becoming octopus, the protagonist Ben operates in the world as a pedagogue: he is a self-selected tutor of an eight-year-old boy from El Salvador, an artist / critic-in-residence at Marfa, as well as a university professor. A glance at three scenes in which Ben performs these roles should illuminate the novel’s finesse in conveying the intimate entanglement of Stanley’s and Trask’s clashing orientations toward experience and pedagogy. The first plays out as dicey slapstick; the second as strained farce; the third as realist drama—not quite tragedy, but not comedy either.

In the first scene Ben takes Roberto on a field trip to the Museum of Natural History and undergoes so many “proprioceptive breakdowns” while in charge of the boy that he deems himself “no more a functional adult than Pluto was a planet” (148). Almost losing him in the subway and again in the museum, Ben does manage to pull his adult self together sufficiently to return the kid to his mother. Almost a parody of Hum 6’s experiential learning in which, as Trask explains, the aim was gradually to withdraw the supervisory teacher from the classroom (Trask, Camp Sites, 57), the turbulent undertow of the field trip episode throws troubling light on this proposition. The second scene brings into Lerner’s crosshairs the pedagogical value of aesthetic judgment; it involves Ben’s abandonment of disinterest for immersive experience. While at Marfa he describes his previous assessment of the sculptor Donald Judd’s work as a formalist (or New Critic) might: “I believed in the things he wanted to get rid of—the internal compositional relations of a painting, nuances of form.” He is “left cold” by Judd’s “desire to overcome the distinction between art and life, an insistence on literal objects in real space” (Lerner, 10:04, 178). But now, “as an alien with a residency in the high desert,” Ben morphs into an Emersonian beholder whereby the experience of Judd’s artwork and everything around it—the former artillery shed in which it is housed, the changing light outside that re-colors the dry grasses, the antelope momentarily glimpsed—serve “to collapse [his] sense of inside and outside” (179). Still able to discern, as a formalist might as well, “the material facts” of the piece with instructive precision (179), he now makes grandiose as-if conjectures, intuiting a likeness between the Judd piece and Stonehenge: it is “a structure that was clearly built by humans but inscrutable in human terms, as if the installation were waiting to be visited by an alien or god” (180). This slog toward sublimity reaches its farcical height when “alien” Ben relegates the sculpture to the status of an object fit for climate change: it is “tuned to an inhuman, geological duration, lava flows and sills, aluminum expanding as the planet warms” (180).3 Ah Judd, ah humanity.

In the third scene Ben, shall we say, returns to his liberal senses, displacing wistful naturalism with sober judgment and practical engagement. Ben’s protégé Calvin, it seems, has ingested too many amphetamines but also, as dispensed by his professor, too much deconstruction—which amounts to a kind of Emersonian pragmatism on Adderall. Besides harboring apocalyptic visions of environmental catastrophe and various conspiracy theories, Calvin is unable to ironize—to be both inside and outside—the deconstructive truth of “how the materiality of the writing destroys its sense” (216); he is left dangerously unmoored by “what we talked about in class” (216). Rather than becoming octopus as with Roberto or transparent eyeball as with Judd, Ben becomes resourceful organization man. He reaches out to colleagues, the department chair, and various students who, he hopes, might help Calvin, given the university’s poor “psychiatric services” (218). Even the distressed Calvin sees that Ben is doing “[his] job,” that, in his solicitude, Ben “represent[s] the institution” (219). Calvin’s abrupt departure, however, suggests that Ben may be a day late and a dollar short in this attempted rescue. Nevertheless, the scene registers Ben’s crucial access to a less ironic, less experience-based institutional style. It suggests that the romance of Emersonian pragmatism may do well to be tempered by the practice of rational judgment so as better to meet the contingencies of the way we live and learn now.

2.3.21 |

Response

Nineteenth-Century Shock Value

Thanks in large part to Walter Benjamin, modernist criticism has excessively “normalize[d] shock as the sole variety of experiential suddenness” (13), writes Kate Stanley in Practices of Surprise. Stanley’s call for the demotion of shock as a category of analysis—setting up an alternate narrative of modernism with, instead of shock, surprise at its epicenter—incidentally recalls the opening of another excellent study of American literature: Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection (1997). Hartman writes there that too often the stories told about racialization and the legacies of slavery “exploit the shocking spectacle” (4)—as in Frederick Douglass’s account of the torture of his aunt Hester—whereas in fact such “shocking displays obfuscate . . . more mundane and socially endurable forms of terror” (42).

Neither shocking displays nor mundane terrors play a major role in Stanley’s subtle readings of Proust, James, Larsen, and Stein. Through the resonances that Stanley draws out between their work and several interwoven strands of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s understanding of temporality, epistemology, and perceptual experience, these readings taught me to see the modernists in a new light. They also helped me reconsider another moment in Douglass’s narrative. Or narratives, really, since it’s a moment he revises, the details of which revision offer a point of departure for some questions about the ethics and influence of Emersonian surprise, particularly when this concept is put in conversation with other voices of the period during which Emerson wrote his most influential essays.

In 1833 the slaveholder Thomas Auld sends Douglass to work the fields overseen by Edward Covey. In a well-known passage, Douglass describes Covey’s serpentine techniques of surveillance. From the 1845 Narrative:

He had the faculty of making us feel that he was ever present with us. This he did by surprising us. He seldom approached the spot where we were at work openly, if he could do it secretly. He always aimed at taking us by surprise. (65)

Many other readers have elaborated on the insights that Douglass offers here on the spatial and psychological operations of panoptic discipline, locating Covey’s fields somewhere between Bentham’s prison and Foucault’s carceral society. But Stanley’s attention to how “surprise can paradoxically be facilitated by preparation” (4) might alert us to other meanings, other effects, in the small choices that Douglass makes in writing and re-writing the scene. Here’s the same moment as revised in My Bondage and My Freedom:

He had the faculty of making us feel that he was always present. By a series of adroitly managed surprises, which he practiced, I was prepared to expect him at any moment. (157)

In the 1845 text, “surprise” was closely connected to active verbs—“surprising us,” “taking us by surprise.” In 1855, surprise has been emphatically nominalized and objectified: “adroitly managed surprises, which he practiced.” Whereas the explicit purpose of Covey’s program of torture is to make other persons “manageable” (a term Douglass underscores elsewhere), here what he manages are his own techniques. Douglass’s revisions present Covey’s influence as a more mediated thing, while his own response to these routines of surprise takes a more pointed, more agential, shape. (Life and Times of Frederick Douglass changes a comma, too, but let’s leave that for another day.) In short, Covey’s practice of surprise produces conditions in which Douglass becomes prepared to expect.

Such preparation by surprise is precisely not what Stanley describes as preparation for surprise. Rather, it echoes D. A. Miller on paranoia: surprise “is precisely what the paranoid seeks to eliminate, but it is also what, in the event, he survives by reading as a frightening incentive” (164). (Miller’s line is also quoted in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s influential essay on paranoid reading and reparative reading, which I mention because I found Stanley’s connection between pragmatist models of perception and Sedgwick’s argument stimulating—I’d love to hear more—even though it is only explicitly addressed briefly in the endnotes [183n40].)

From Miller’s description of paranoia, it’s a short hop to what Stanley says about the way that perceptual preparation might run the risk of becoming a routine: “The task of preparing to be surprised is easily inverted into the task of preparing not to be surprised,” in that such a task might “seem to suggest transforming volatile phenomena into regular, even routinized experiences” (3). By contrast, Stanley’s sense of surprise, a preperceptual openness that resists routinization and preconception, has shades of Heideggerian waiting versus awaiting (“in waiting we leave open what we are waiting for,” says the Teacher in “A Conversation on a Country Path about Thinking” [68]), and also of anthropologist Tim Ingold’s sense of the “perpetual astonish[ment]” of “those who are truly open to the world” (75). Ingold, it should be noted, contrasts such astonishment with “surprise,” which he denigrates as “the currency of experts who trade in plans and predictions” (63), but substantively his view of things would seem to affirm Stanley’s.

Even as I learned from the novel connections that the book draws between Emerson and later writers, I wonder about the centrality and even the necessity of the former. Although the Proust chapter works to imagine literary historiography outside its usual lines of descent, Practices of Surprise does seem invested in an account of “influence” (see this term at for instance 4, 30, 55) and even inheritance (29, 57), and when one influential figure is so strongly stressed it’s hard not to wonder about the gaps in the family tree, the laterals left aside. Bergsonian duration surely would have been just as relevant as Emerson to the account of temporality in Stein, for instance. And Charles Sanders Peirce does not rank in the narrative of pragmatism offered here, despite centering a theory of knowledge on ideas about surprise, through his concept of abduction as the logical process by which scientific inquiry tries to make sense of “surprising facts,” viewing “them in such new perspective that the unexpected experience may no longer appear surprising” (28).

Those examples’ absence is no cause for criticism; I mention them mostly as a small sign of the stimulating spread of the ideas introduced here. But the strong view of Emerson’s line of influence does, I believe, produce at least one straw man in the figure of W. E. B. Du Bois. The chapter on Nella Larsen culminates in a revelatory reading of Quicksand (and particularly of the emplotment of its ending). Along the way, the chapter asserts that insofar as we talk about “double consciousness” in Larsen’s work, it should not be through a Du Boisian framework but rather through the “original” (31, 119, 120) sense of this term—that is, Emerson’s (though it is slightly odd to call this original given the earlier uses of the phrase in medical discourse). Here, Du Boisian double consciousness is taken to assert only rigid conceptual binaries—white/black, interior/exterior—whereas Emersonian double consciousness names a sense of atmospheric flux that is more fitting for the subtle, shifting “weather” of Larsen’s narrative. Emerson’s insights about ambience receive a patient, incisive exegesis, but Du Bois’s concept is assessed and dismissed based on minimal evidence, as though it were a concept that admitted of straightforward definition. That evidence includes a quotation of Du Bois’s account of “two thoughts . . . torn asunder” (Stanley 120), but the elision in that quotation slightly changes the line’s meaning; Du Bois actually writes in The Souls of Black Folk that these two thoughts coexist “in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder” (5). The thoughts aren’t the objects torn asunder; they’re what threatens to do the tearing. They may be “warring” but are not rigidly separated: they tangle in the body. And if we look more widely across Du Bois’s description of the formation and experience of double consciousness, we can see that he actually does develop a pattern of atmospheric tropes not so unlike Emerson’s. Consider: “an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came home upon the four winds” (10). Or: “Much that the white boy imbibes from his earliest social atmosphere forms the puzzling problems of the black boy’s mature years” (118). We could find plenty of other places in Du Bois that develop similar language: skies, clouds, shadows. If such moments received the same attention that Emerson’s prose does here, it seems possible that we’d end up similarly complicating any initial sense of how double consciousness works for Du Bois, and how his thinking grapples with the flux of lived experience.

This is a disagreement regarding a relatively small claim, I realize, about a single writer in a book that convinced me about many others. I mention it, though, because on reflection it led me to a broader question about how the conversation here around surprise might change were it to dwell on more figures who, as Herman Melville wrote in 1849, “do not oscillate in Emerson’s rainbow” (Correspondence, 121)—and therefore who may have helped, by way of counterpoint, contrast, or illocutionary backdrop, give shape to the meaning of Emerson’s concepts.

Which brings me back to Douglass’s responses to Covey. Consider again the way that he describes the perceptual routine of expecting these “surprises” that are not surprises. It’s both an internalization of discipline and a survival tactic. Awaiting and prediction—the techniques of the paranoid—may not be as reparative or as illuminating as other practices of surprise, but surely they name a way of getting by in the context of Covey’s fields. Beneath this observation is a potential reservation about the politics of Emerson’s thinking that Practices of Surprise has already to some degree anticipated (but that I believe merits further discussion) in, for instance, its remarks on the essay “Circles.” Emerson writes: “The one thing which we seek with insatiable desire is to forget ourselves, to be surprised out of our propriety, to lose our sempiternal memory, and to do something without knowing how or why; in short, to draw a new circle” (quoted in Stanley 23). (And by the way, Emerson’s metaphor and argument are perfectly transmuted in the John Cage drawing selected for the book jacket.) Stanley acknowledges that Emerson’s argument, his sense that we’re all comfortably settled and need to shake things up, might “sound like a solipsistic endeavor available only to a privileged few” (24). I’ll confess: yes, I’ve always heard a hint of this. This is not least because, in my experience teaching this essay (and it is an essay that greatly rewards teaching), students often, at some point in the discussion, raise a question whose thrust is something like: What does it mean to dismiss the value of personal autonomy in a society where that is already being systematically denied to millions of people?

In a defense that struck me as slightly (forgive me!) circular, the argument at this point refers us to Emerson’s own insistence: “However, Emerson insists that seeking such surprises is a necessity, not a luxury. ‘The results are uncalculated and uncalculable,’ he writes, and these unknown odds expose all living beings to contingency and risk” (24). Of course, calling a luxury a necessity is also a tried and true sales tactic. I don’t mean to suggest, exactly, that we ought to reject Emerson’s argument—his call for unsettling the self—on the grounds of, say, the sanctity of the bounded liberal individual. For just one of many ways to trouble that category, we could look to Édouard Glissant’s description (and, adapting Glissant’s words in his recent work, to Fred Moten) of the entry into diaspora as “the moment when one consents not to be a single being and attempts to be many beings at the same time” (5). There may be a way to talk about such pluralities and Emersonian flux in the same breath. But this needn’t lead us to elide the distinction between what Judith Butler calls “precarity” (that is, the condition of being rendered particularly exposed to violence and disease) and the universal fact of mortal precariousness. With a sense of universality that echoes an Emersonian claim about “all living beings,” Melville’s Ishmael claims that “all men live enveloped in whale-lines,” whether on a whaling boat or sitting at home comfortably before the hearth (281), but many other moments in Moby-Dick—the racialized conditions of authority in which Pip becomes vulnerable to just such a whaling line, for instance—cut against this, dramatizing the unequal distribution of contingency and risk.

“Shock” offers still another way, in Emerson’s moment, and in abolitionist discourse in particular, to talk about that inequality. Shock is not just different from surprise in its intensity or in the experience of the perceiver. It construes a different kind of thing in the world (an event, an action, a circumstance, a law), and it entails a moral judgment about that thing. Harriet Jacobs describes in her narrative the way that “town patrols were commissioned to search colored people that lived out of the city; and the most shocking outrages were committed with perfect impunity” (103). Charles Sumner says in a speech, much quoted, that the Fugitive Slave Act “violates the Constitution, and shocks the public conscience” (298). By contrast, when John Greenleaf Whittier uses “surprise” rather than “shock” to describe his response to Daniel Webster’s support of the 1850 Compromise (leading Whittier to write “Ichabod”), he knows he’ll have to add some more language to convey the affective and moral dimensions of his response: “surprise and grief and forecast of evil consequences” (184).

So I’m left wondering: what does Emersonian surprise look like when what we set it against is not Benjaminian or Freudian shock—a response to “the onslaught of war, urbanization, and technological change at the turn of the twentieth century” (Stanley 10)—but rather the moral shocks, the sentimental appeals, of Emerson’s lifetime? And how might this way of re-situating the conceptual formation of surprise affect our sense of what it means for Emerson’s writing to echo in these later texts? Perhaps we’d simply come up, again, against one of the key points that Stanley makes: that “Emerson’s larger claim is that ethical investments should not bolster preconceived certainties but should acknowledge the state of contingency that human life, like nature, inevitably asserts” (25). Perhaps, that is, invocations of moral shock do rely on and “bolster preconceived certainties” in their assumption of static principles of value, so that in looking back to nineteenth-century shock we would only find another limited framework that doesn’t possess the qualities of openness to which Emerson attunes us.

On the other hand, such shock could also be understood as potentially transformative. Elsewhere in My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass plays with the language of moral shock in describing his belief that the enslaved person is fully entitled to steal. He sardonically calls his own argument “a profession of faith which may shock some, offend others, and be dissented from by all” (140). Here he acknowledges his readers’ potential recoil from whatever is counterintuitive in this argument, a recoil stemming from some moral preconception, some prior value. But his reference to this response does not reaffirm those assumptions. It calls them out, invites their reconsideration, estranges them. Covey’s “surprises” are meant to discipline. Here, Douglass’s “shock” aims to teach.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? New York: Verso, 2016.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. New York: Penguin, 2003.

———. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. New York: Penguin, 2014.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Penguin, 1996.

Glissant, Édouard, and Manthia Diawara. “Édouard Glissant in Conversation with Manthia Diawara.” Translated by Christopher Winks. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 28 (2011), 4–19.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Heidegger, Martin. Discourse on Thinking. Translated by John M. Anderson and E. Hans Freund. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

Ingold, Tim. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description. London: Routledge, 2011.

Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself. New York: Penguin, 2000.

Melville, Herman. Correspondence. Evanston: Northwestern-Newberry, 1993.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; or, the Whale. Evanston: Northwestern-Newberry, 1988.

Miller, D. A. The Novel and the Police. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Moten, Fred. consent not to be a single being. 3 vols. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017-2018.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Edited by Arthur W. Burks. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1966.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Sumner, Charles. Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner. Edited by Edward Lillie Pierce. Vol. 3. London: Samson Low, Marston, 1893.

Whittier, John Greenleaf. The Complete Poetical Works of Whittier. Edited by Horace E. Scutter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1894.

2.10.21 |

Response

What We Mean by Paradox and Why It Matters

Let’s say we speak pragmatically. If this is the case, I may dispense quickly with praise here. I’ll leave it to other commentators (and there will be many) to mark this book’s accomplishment and insight. Instead I’ll trust that my extraordinary admiration is communicated, implicitly, in the questions that follow. Because, in the best pragmatist tradition, Practices of Surprise presents not a “solution” but a “program for more work.”

And I want to get to it.

“How does one prepare to be surprised?” Stanley begins, drawing out the tension implicit in the question (3). Surprises are, after all, “events for which one is the opposite of prepared” (3). Or, to put the conflict more clearly: “The task of preparing to be surprised is easily inverted into the task of preparing not to be surprised” (3).

For Stanley, however, preparation and surprise are not merely at odds with one another. Rather, Stanley insists, the idea that one might “methodically establish a readiness for surprise” presents us (and her writers) with no less than an “epistemological paradox” (33).

Stanley calls this “the Paradox of Preparation,” and there are good reasons for her to frame the question so forcefully. As she points out, the wish to avoid surprises—to mitigate them, defend against them, prepare for them—has long dominated our critical account of this period. The key term here is “shock,” and Stanley is precise in tracing its circulation, from Benjamin to Agamben, such that I need now only gesture at the ways in which the term—and all the structures it implies: its perceptual framework (the eye), its relation to time and to memory (trauma), its relation to the environment (the city)—has come to shape our understanding not only of literary modernism, but of modernity itself.

For the reader steeped in this critical tradition, the question “How does a person methodically establish a readiness for surprise?” may appear intractably difficult—no less than the full-blown “paradox” that Stanley describes (33).

And yet, the moment one steps away from this context, “preparation for surprise” does not present itself as a paradox at all—not really—and not just because the book itself of course resolves that conflict. It’s not a paradox, I would argue, because it’s not one on its face—which is to say: it’s not a paradox by our most ordinary and familiar measures of what we call experience. “Preparation for surprise” might even reasonably be considered a definition of practice as such—“practice” of the most ordinary, colloquial kind—the kind that athletes and musicians and dancers and doctors do.

The “preparation” here is of course of a specific kind. (One may prepare for a hurricane by closing the windows or one may prepare by opening them; the distinction is an important one.) Still, for most of us, the concept of a form of discipline designed to be openly responsive to contingency is not only non-contradictory, it’s in fact familiar—from baseball to baking, ceramics to sex.

To acknowledge the ordinariness of this structure—to acknowledge it as a familiar field of “action”—is in no way to disparage the work of the book, but rather to confirm its feeling of rightness.

I worry about the use of the language of “paradox” though, or point it out, because there is a real, robust sense of paradox that comes later in the book—a “paradox” that is in fact critical to Stanley’s argument, one that has a precise and even technical function in pragmatist thought.

Needless to say, this is a “paradox” very different from this first one, though not always easy to distinguish. This second paradox is registered in the body, and is one of the key experiences of mind that Emerson and William James, amongst others, draw upon regularly in their work.

This form of paradox is utterly distinct from what we mean when we use the word to describe something that is merely contradictory on its face—something that can conceivably be, with argument or consideration, resolved.

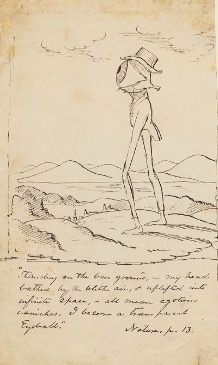

Stanley’s brilliant reading of the “transparent eye-ball” (64) begins to gesture at Emerson’s use of “paradox” in this second, robust sense. As Stanley points out, Emerson, unlike Plotinus, refuses a longstanding distinction between physicality and sight. His figure of the “eye-ball” makes literal the idea that one “becomes vision” (64), and in so doing, Stanley shows, Emerson effectively resolves an apparent impasse.

But it is worth noting that Emerson’s intervention here is not merely philosophical. Rather, the “eye-ball” works in a second rhetorical register as well. When we encounter the line,

“I become a transparent eye-ball,” we are ourselves, as readers, caught up. Any attempt to fully comprehend this image (the impossibility of locating the line of vision; the problem of its materiality—both transparent and an eyeball; its position in the body and out of it at once; its potential literalism and its status as metaphor; etc.) produces a kind of interpretive oscillation that has no apparent resting point. The experience of attempting to “resolve” this image becomes its own kind of circle, one that makes manifest the idea of our own “embodied” vision—circumscribed even in imagination by the body. And in this form of paradox—one which honestly, experientially baffles; one in which it’s possible to understand without fully grasping—we are given a first-hand insight into what it might really mean to in fact “become an object and potentially ourselves” (Plotinus, quoted in Stanley 65).

* * *

To some this distinction will seem quibbling, but Stanley is well aware of the stakes here. As she compellingly argues, a very great deal relies on our ability to agree upon what constitutes an “authentic” paradox, as opposed to a mere semblance of one. Her account of New Criticism shows two paths, forking “precisely at the point that the New Critic installs the concept of paradox as a core tenet of close reading” (40).

On the first path, interpretation produces only its own reflection, “reinforcing its own inevitability as every new example of paradoxical language is uncovered in the closed critical system” (40). But there is, she points out, another way—one modeled by the technique and discipline of embracing the “practice of surprise.” In this model the teacher will likewise “lay out a paradoxical problem presented by the text” (51). In this case, however, the paradox is not imposed upon that text, but rather, emerges from it (51).

Stanley’s own teaching practice reflects this second path. Still, as she readily admits, there is a “potential pitfall in structuring a class like this” (51). Though the right kind of paradox may be demonstrated (pointed to, repeated, pointed to, discussed, repeated, and so on)—it is not subject to easy or even plain exposition.

Emerson’s notorious difficulty attests to this point. As a young reader, that “transparent eye-ball” struck me as weird and abrupt—even perhaps a little bit hokey. (See this goofy—though now iconic—drawing, by Christopher Pearse Church.)

As an adult, I perceive the line differently of course—but I may just as easily have missed it.

I have argued that the line makes Emerson’s argument manifest in the experience of the reader. I should have said: in the reader going slowly enough; in the reader with a teacher to guide her.

I have argued that the process of preparing oneself for surprise does not present an inherent paradox (and I maintain that it doesn’t). But, as Stanley so clearly elucidates, preparation for surprise is nevertheless a perilous process: one vulnerable to fraudulence and fakery, one that opens itself to misinterpretation and misuse, from zombie formalism to idiot compassion.

Which is why it is worth arguing about.

Practices of Surprise offers us this privilege.

2.17.21 |

Response

Paradoxes and Problem Solvers

In Practices of Surprise, Kate Stanley offers a thoughtful, reflective alternative to the shock-centered aesthetic of avant-garde modernism. Her claim is that Emerson’s vision, inherited by, echoed within, and refracted through a range of modernist authors—including Stein, James, Larsen, and Proust—offers the experience of “surprise” as a carefully managed counterpoint to shock. This is not the assaultive, violent surprise of an aggressor leaping from behind a door. Rather, it’s a welcoming vision of surprise—one that reminds me of my son’s insistence, when he was three years old, that strangers were “friends I haven’t met yet.” It’s the cultivation of such an accepting mindset with regard to unexpected concepts, ideas, and aesthetic experiences, that Stanley’s key figures model, and that this lovely book celebrates.

It does so by demonstrating how this “yielding mode of receptive surrender” (79) is achieved not simply through lucky accidents of character and orientation, but is cultivated carefully over time. Stanley takes the traditional story of shock—the quintessentially modern experience of depletion, alienation, and defensiveness—and transforms it into the opportunity for improvisatory, creative, and generative responses to the unexpected and unknown. This process is embodied in Emerson’s stance of radical openness to the world, to which Stanley’s opening chapter is devoted, and which remains a touchstone for the chapters that follow.

The body of her book traces the ways in which a variety of modernist thinkers succeed in carrying on Emerson’s legacy, not only in their experiments with language but in their dogged cultivation of openness and vulnerability in the face of surprise. The book is as much an appreciation and celebration of the texts it examines as it is a series of interpretive claims. In many ways, its subject is love—the love of particular texts, the way we rediscover our love for those texts, the ways in which those texts take our breath away, and how we can sustain such love over time. It’s also about the bonds that arise between teachers and students, genealogies of influence such as those that have been used to tell the story of pragmatism by thinkers as divergent as Cornel West, Jonathan Levin, Richard Poirier, and James Kloppenberg. This is influence without anxiety, however: in this anti-Bloomian narrative, Oedipal struggle is replaced by affection, indebtedness, and cathexis, often unconscious and unacknowledged. In this sense, the book constructs a pragmatist genealogy that is as much emotional and spiritual as it is intellectual. Indeed, the conclusion of Stanley’s first chapter is an extended meditation on the circles of pedagogical and intellectual influence that emanate not only from Emerson, the prime mover in multiple cosmologies of pragmatism, but also from Richard Poirier, the intellectual father or grandfather of most—though not all—literary scholars working on pragmatism today. This question of pedagogical influence is a key component of Stanley’s theory of “cultivated” surprise, in part because the practice alluded to in the book’s title is primarily a skill and not a concept, and the classroom is her model for how such skills are transmitted and internalized over time.

Stanley presents her ideal of cultivated surprise as the solution to an intractable paradox: how does one “prepare to be surprised” (3)? How do we make “newness a routine,” especially when—in Michael Clune’s words—“time poisons perception”(Clune, quoted in Stanley 2)? Here too, her proposed answer is taken from the realm of the pedagogical: “As veteran teachers (similar to, say, proficient musicians) might attest, from a state of adaptive preparation and adept responsiveness, unforeseen spontaneity and inspiration can spring forth readily, even under the most familiar and reiterative circumstances. The goal of education as James frames it, is to programmatically cultivate such spontaneity as a lifelong habit” (6).

The idea that surprise can offer an alternative to shock, that it can be cultivated and developed over time, that key authors of the modernist moment committed themselves to this pedagogical project in ways that have been overlooked, and that the cultivation of such spontaneity would depend upon the right sorts of habits, are insights that share a good deal with the arguments of my first book, Pragmatic Modernism (Oxford, 2012), which Stanley insightfully and generously reviewed in Criticism in 2014. Spending time with this book has given me an opportunity to think about what it might mean to emphasize surprise as a central concept, as Stanley does in her book, rather than habit, the key term of mine. I want to develop this distinction a bit because it helps me to capture what I find especially original and moving about Stanley’s book. It also, as I’ll go on to argue, allows us to think with greater clarity about a longstanding divide in pragmatism-inflected criticism.

While both “habit” and “surprise” may work in concert to cultivate flexibility and openness to experience (the hallmark of all pragmatist thought), they are not simply complementary terms. Habit is first and foremost a philosophical or psychological concept. It describes any specific component of thought or behavior that has become automatic enough to be invisible. Surprise, on the other hand, is not a concept. It is an affective state, an emotionally-charged, fleeting, temporary experience. This flexible and capacious term indicates experiences that expand the self as well as the self’s conception of the world (in contrast to those shock-centered experiences which, in Simmel’s classic account “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” shrink itself into defensive formations such as “the blasé attitude”). Surprise has implications that are ethical, aesthetic, and emotional. It helps to describe an openness to otherness that has Levinasian resonances; it also can help to describe what makes a prose style great. But most importantly, it captures a feeling, an emotional response that grips readers, writers, and thinkers when their established expectation or their sense of the known suddenly expands. To build an argument upon an affective state such as this one brings a very different charge to the discussion—it brings, among other things, a renewed emphasis on the emotional, affective, ethical, and aesthetic elements of the works under discussion and the problems that are being considered.

Stanley’s opening paradox (“making newness a routine”) can be made to dissolve when the problem is framed in terms of habit, and when we imagine the creation of new habits that are, in Dewey’s words, “more intelligent, more sensitively percipient, more informed with foresight, more aware of what they are about, more direct and sincere, more flexibly responsive than those now current” (HNC, 90). To replace surprise with habit, then, is to replace the affective experience of paradoxical puzzlement and bewilderment with a characteristically pragmatist shrug of acceptance and getting on with things. To replace habit with surprise, on the other hand, is to shift into a different temporality, to linger in the slowed-down hinge between habit and shock, taking it as an opportunity for reflective analysis. Both activities are important, and there should be space in pragmatist criticism to accommodate both of them.

Indeed, a major contribution of Stanley’s book is the way her readings continually remind us that “all depends on the feelings things arouse in us” (James, quoted in Stanley 104). Surprise is an affective state of arousal, and it is just one of the inchoate, emotionally-tinged elements of our experience as readers, teachers, and scholars of literature to which she is able to give voice in this book. Her explorations of modernist authors finds her tracing affective and aesthetic dimensions of these authors’ work that have often been taken for granted or simply overlooked. Thus we are given Proust’s extended descriptions of what it feels like to read; we are shown how Larsen’s descriptions of weather work to capture Helga Crane’s attuned sense of “atmosphere,” a sort of electrified hypersensitivity to her surroundings and their emotional charges. We see how James’s navigation of surprise and recognition, the “scenic” and “non-scenic” systems that make up experience, function as his exploration of the psychological problem, treated so brilliantly by his brother William, of how emotions work. We are treated to Stein’s unforgettable description of what it feels like to write, as reported by Thornton Wilder:

Now if we write, we write; and these things we know flow down our arm and come out on the page. The moment before we wrote them we did not really know we knew them; if they are in our heads in the shape of words then that is all wrong and they will come out dead; but if we did not know we knew them until the moment of writing then they come to us with a shock of surprise. (Wilder, quoted in Stanley 155)

In each of these cases, Stanley’s concept of surprise shows us what it feels like to negotiate the hinge between habit and shock and to cultivate the habit of openness to the unfamiliar or surprising. Like the dialectic of habit I describe in my book, Stanley’s account describes a pendulum swing between habit and disruptions to habit, as such phrases as “protracted disorientation and reorientation” (28) “perceptive undulation and literate spontaneity” (44) suggest. But to develop this idea, Stanley turns not to James or Dewey, but to Silvan Tomkins, the father of affect theory. According to Tomkins, surprise can be a “circuit breaker” “when it interrupts a prevailing feeling and clears space into which new responses can arrive” (25). This is meaningful because, according to Emerson, it can break “my whole chain of habits, and . . . open my eye on my own possibilities” (26). That Stanley reaches for Tomkins and Emerson here rather than to Dewey or James may suggest that she is less interested in describing how this process works than she is in capturing how it feels.

This emphasis on the feelings of reading and writing places Stanley in the intellectual tradition of Richard Poirier, an inheritance she acknowledges in her introduction. She shares Poirier’s conviction “that the most important question is not ‘what does this writing mean?’ but ‘what is it like to read this?’—confusing? reassuring? intimidating? cozy? all of these at once?”1 We may also feel echoes of Poirier in the way that Stanley uses the category of surprise to help describe the magic that makes truly transcendent, original, and moving prose. Emerson (himself the very incarnation of such magic) provides the language for Stanley’s reflection about this question, describing his own work, for example, as featuring “a spontaneity which forgets usages, and makes the moment great” (Emerson, quoted in Stanley 21); and reminding us that “the word should never suggest the word that is to follow it, but the hearer should have a perpetual surprise, together with the natural order” (Emerson, quoted in Stanley 18).

Emerson’s ability to explain and describe his own compositional process, and the magic to which this process gives rise, explains why he is the origin point not only for Stanley’s argument, but also for Poirier’s own genealogy of pragmatism. Poirier valued above all else the way that language transforms itself and comes alive, through what he calls at various moments “troping,” or its “active, struggling, exploratory, and exultant performing presence” (Poirier, “Pragmatism,” 76). These various terms for the vivid, complex, self-negating elements of language could also be described as its paradoxical elements. And indeed, paradox plays a key role in Stanley’s account. Not only is her argument a response to the paradoxical question, as I’ve already described, of how one prepares to be surprised; but the internal circuitry and centrifugal force of paradoxical language becomes a figure for the larger experience of surprise, and captures what is complex, challenging, and surprising about the experiments in prose she analyzes. Paradox is also key to understanding the revelatory language and thrilling reflections of Emerson, from whose work her argument—like Poirier’s—takes its inspiration.2

The language of poetry might be the language of paradox, but the language of habit—Dewey’s language—is the language of change across time. Unlike Emerson, Dewey had little use for paradox. He didn’t particularly relish lingering in puzzling dilemmas or insoluble contradictions—indeed, he didn’t really do much lingering at all. Rather, his approach was based in identifying and then solving problems. I bring this up because it points to a distinction between thinkers who approach pragmatism as a set of concepts, key terms, ideas, and values (problem solvers, we’ll call them), and those who interest themselves in pragmatism first and foremost as a mode of expression (we’ll call this group the paradoxical thinkers, and take Poirier as an exemplary case).

In her book, Stanley does make an effort to connect these two constituencies, here represented by Emerson and Dewey, doing her part to reestablish this missed connection of intellectual history by bringing in Dewey early in the book as a champion of Emerson’s work. Her emphasis on the importance of the classroom is also characteristic of a problem-solver’s interest in questions of transmission, communication, and practice. Still, her sympathies ultimately lie with the thinkers who choose living language over water-tight argumentation, as her book’s deep attention to tracing, describing, and meditating on the thrills of pragmatist language clearly demonstrates.

I value the way that Stanley, following in Poirier’s footsteps, encourages me to be reawakened to my own experiences of wonder and surprise when confronted with the sort of living, complex prose to which most literary scholars, and certainly those of us who gravitate towards modernist literature, are drawn. But there is also a place, I would argue, for a pragmatism that is not in and of itself a form of art but that instead attempts to express, explain, and discuss its own ideas and concepts without necessarily typifying those concepts through its own self-consciously paradoxical language. Take Dewey, and his greatest contemporary champion, Richard Rorty: Dewey was a problem solver, a civil engineer, a skeptic, an elucidator, a planner, a skeptic, an educator. Rorty was a brilliant translator of concepts, an explainer, a simplifier, a connection-finder. Both thinkers loved and admired artists immensely, and shared their own theories of art (Contingency, Irony, Solidarity, and Art as Experience), and both were able to turn the occasional felicitous phrase—but neither could be said to have been artists themselves, certainly not in the sense that we may say this of Emerson.

In his review of Poetry and Pragmatism, as Stanley notes, Ross Posnock expresses bemusement at Poirier’s seeming imperviousness to Dewey’s contribution.3 But Poirier is hardly alone in this omission: Stanley Cavell’s essay “What’s the Use of Calling Emerson a Pragmatist?” is little more than a collection of withering potshots at Dewey’s perceived flat-footedness, naiveté, and lack of emotional depth (failures Cavell assumes he shares with the philosophical movement of pragmatism as a whole).4 Certainly, after the Turkish delight of Emersonian sentences and paragraphs it can be hard to be satisfied by a few stale crusts of Dewey’s prose. But this is more than a matter of aesthetic taste and personal preference: Poirier’s rejection of Dewey’s flatness is fundamental to his understanding of what pragmatism is and what its importance for literature might be.

“In Pragmatism and the Sentence of Death,” Poirier explains why he sees pragmatism as the philosophical incarnation of literary greatness:

The greatest cultural accomplishment of pragmatism remains the least noticed, and one which it never very clearly enunciates as a primary motive even to itself. It managed to transfer from literature a kind of linguistic activity essential to literature’s continuing life but which it now wants effectively to direct at the discourses of social, cultural, and other public formations, always with an eye to their change or renewal. (86)

This argument insightfully connects the strenuousness of literary language with pragmatism’s inexhaustible struggle for social and political transformation. But Poirier’s simile—that the restlessness of literary language is like the restlessness of endless pragmatist inquiry—runs the danger of conflating the two categories it compares.

First, pragmatism did not invent and is not necessary to experiments with language. While Poirier is brilliant in identifying the points of contact between pragmatism and its so-called “poetry,” and while it is certainly true that the philosophical commitments of, e.g., Emerson, Stein, James, Proust, and Stevens are instantiated in their use of language, it is simply not the case that all “troping,” as Poirier calls it, is intrinsically, essentially pragmatist. “Linguistic skepticism” and emphasis on “the moment of passage” are features that can be identified in the work of many brilliant writers. In “Pragmatism and the Sentence of Death,” Poirier’s catalogue of works “that display an agitated, critical responsiveness to their own language” (84) includes Shakespeare, Marvell, Swift, Henry James, Wordsworth and Dickens.

In this sense, Poirier’s claims for pragmatism seem to me to be much broader than pragmatism itself—indeed, they seem to take in the whole sweeping vista of literary and linguistic achievement. From another perspective, though, his vision is far more restrictive than pragmatism’s vision allows. Specifically, individual wonderment, reflection, and personal transformation (the key elements of the paradoxical approach to pragmatism) do not begin to address collective and institutional change across time, social experience, or the social world.

At such moments, when we become interested in developing, for instance, a theory of social transformation, paradox can begin to feel a little bit static. While there can be lots of movement within the circuit of the specific contradiction (and this can generate the electricity of a particular sentence or certain elements of the aesthetic effect of Emerson’s prose), a paradox can’t (and doesn’t want to) capture movement forward across time.

Poirier’s approach demands that philosophers be artists. But what he shows is not that pragmatism is great literature, but that great literature gives us a glimpse of pragmatism’s characteristic action avant—or après—la lettre. His argument is convincing because his chosen philosophers, Emerson and James, so happened to be artists or at least very fine and imaginative authors of highly literary prose. By the same token, Dewey’s exclusion from his pantheon makes sense because Dewey’s prose does not embody what Poirier sees as properly “pragmatist” values.

I am tremendously sympathetic to the aesthetically complex demands of paradox-based pragmatist criticism, and convinced by the way this approach, wielded expertly by Stanley and informed by a deep background in affect theory, brings her readings to life and emphasizes the emotional and aesthetic impact pragmatist criticism is capable of imparting. Poirier and his followers have done a crucially important service for pragmatism by placing aesthetic complexity at the very heart of their project. In so doing, they are rebutting a long tradition of thinkers like Lewis Mumford, Walter Lippman, and Louis Hartz who saw pragmatism as synonymous with instrumentalism, positivism, or empiricism, thought it was comfortably hospitable to capitalism, and found it lacking in political meaning, emotional honesty, and aesthetic value.

But I also want to reserve a place for the problem-solving approach represented by Dewey or Rorty. Such an approach has been denigrated for its ability to make seemingly intractable problems disappear by simply disavowing them as problems, as in Dewey’s rejection of philosophical dualisms, or Rorty’s shrugging dismissal of the problems of Western metaphysics. But there are genuine intellectual thrills to be found in these swashbuckling rejections of philosophical pieties, and their disruptions to the well-worn circuitry of philosophical categories can bring breathtaking new possibilities into view. Further, a Deweyan problem-solving approach ensures that questions of collectivity and social transformation remain central to the pragmatist project. It is possible to embrace an ameliorative vision without dismissing history or ignoring the pain and beauty of our broken world. Because pragmatism is a set of procedures, not an ideology, it can include all these elements and more.

Poirier’s pragmatism gives those of us who love language a new reason to love pragmatism, and Stanley’s treatment of surprise gives us a new language to describe that love. Stanley’s book has renewed my sense that the pragmatism’s two strains are not only compatible but complementary. It has given me some new ways to think about how we might bring these positions more closely into alignment with each other, which would, after all, be more in the spirit of thinkers like Proust and James and Stein, for whom aesthetic achievement and the theorizing of collective action and meaning were always inseparable from each other.

Richard Poirier, “Pragmatism and the Sentence of Death,” Yale Review 80.3 (July 1992) 74.↩