The Home of God

By

3.7.24 |

Symposium Introduction

Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz’s book The Home of God: A Brief Story of Everything (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2022) is one of the latest publications by members of the Yale Divinity School’s Center for Faith and Culture. Focusing on two key biblical writings, namely Exodus and the Gospel of John, this book offers a strong case for interpreting the overall aim and shape of God’s action as making a dwelling among creation. The two authors make the case for “home” as a particularly rich and helpful theme (better, they argue, than “temple” or “kingdom”) and as a crucial red thread within the Bible. To them, it is not just “a” central biblical theme, but probably “the” central one, even though this thesis has—to their (and perhaps our) surprise—almost never been stated or explored in the course of two millennia of Christian theology.

After a “Prelude” and an “Overture” in which the stark ambiguity of “home,” as places of growth, joy and love, but also as places of abuse, disjunction and suffering, is taken seriously, and in which the authors acknowledge their debts to other scholars, past and present, the book comprises four parts (most parts comprising two chapters): “Exodus” (part 1), “The Word of Life” (part 2, on John’s gospel), “The Spirit of Life” (part 3, also on John), and, finally, “The Fullness of Life” (part 4, with special reference to the final chapters in the book of Revelation).

Part 1 centers on the central story in the Hebrew Bible, i.e. how God liberates the children of Israel from the “house of slavery.” The Scriptures address the inevitability of dysoikic (17) reality head-on. The event of liberation is not self-enclosed: liberation is given for the sake of life, and not just “any” life, but life as part of God’s household. Here the theme of the tabernacle becomes significant as the tangible sign of God’s presence “in all the travels of the Israelites” (68, quoting Exod 40:36).

Part 2 turns to the “new exodus” (74) signaled by the dwelling of God in human flesh: God came to dwell into and among “his own” (ta idia; John 1:11). The two authors are mindful of the fact that, both in the book of Exodus and in the fourth gospel, “presence” does not go without “absence” (75). They then ponder the continuities and discontinuities between John’s gospel and the book of Exodus: notably, whereas the Hebrew Scriptures envision a dwelling of God among God’s people, the gospel writer speaks of God dwelling in the disciples of the incarnate Word (135).

The eschatological promise and its fulfilment, when our dysoikic realities begin to be and will be wholly healed and transformed into the new world in which God dwells, are the themes of Part 3. The telos of God’s ways is not a flight away from the world, but its transformation. The judgment of Babylon, for the sake of liberation from sin and death, is a key component of the apocalyptic vision of the New Jerusalem in the last book of the Bible. The book of Revelation urges us to look at the final “this-worldly eschatological culmination” (190). All in all, The Home of God is a condensed, compelling theological analysis and account of a key biblical theme. It offers a “biblically articulated theology of life” (28) in the midst of ambiguity and sin, with an eye toward the full realization of God’s intent.

As such, this book deserves a broad critical engagement in order to discuss its main theses, its usage and interpretation of Scripture, its reformulation and reframing of sin (hamartiology as dysoikology, as it were) and liberation. Hence the panel of scholars gathered here to critically appraise Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz’s monograph. In this symposium, no less than seven contributors delve into The Home of God in order to identify and ponder the strengths of the work as well as its weaker points.

In the symposium’s first essay, Keri Day notes the strength and indeed the boldness of the book, insofar as its authors do not merely suggest the theme of “home” as one helpful lens through which we may read the Scriptures, but rather as the best suited theme in order to interpret the canonical texts. Day then raises several other important questions, e.g. on the risks that might come with selecting the gospel of John, thereby leaving the synoptics aside, or on the place of “desire,” both divine and human, in a theological construal of God’s intent to make a home in the midst of creation.

The second essay, by Juliane Schüz, raises methodological questions related to “dogmatic storytelling,” in critical conversation with the subtitle of the book (“A Brief Story of Everything”). How does the narrative approach of the book relate to the classical dogmatic method that centers on established themes or loci? And what are some of the implications of the narrative approach for the treatment of themes such as faith, grace, and sin? Schüz wonders whether the two authors do not blur at times the distinction between divine and human agency.

Emmanuel Durand’s response also begins with a methodological question, on the not always clear underlying “anthropological register” which could facilitate the reception of such a book in today’s world, not just among committed Christians but more broadly. Close attention to Scripture is to be praised, in Christian theology, but the slight risk is then a greater gap with our contemporaries. While Durand expresses deep appreciation for the book, he wonders why the theme of the “city” is not explored in greater depth by the authors.

The fourth essay, by Beth Felker-Jones, applauds the authors for their emphasis on the “worldliness” of God’s project. This emphasis, in her view, “opens us to much needed possibilities for theological imagination and the embodiment thereof.” But, like Keri Day, she suspects the two authors go a bit further than necessary in prioritizing the “home” metaphors over other key biblical metaphors. Scripture overflows with metaphors, so why select one as “the” richest or most significant? And how would the theme of “home” look if other biblical books had been highlighted? A second question follows, on the theme of “home”: shouldn’t the book have paid more attention to the nitty-gritty of homes, including dish-washing, laundry, messy kids’ rooms, and so forth, also with an eye toward the historical roles of women in these homes? And what about the neighborhoods in which homes are built and in which people live, taking into account segregation and red lining practices?

In his essay, Hong Liang places the book in conversation with Jürgen Moltmann’s works (Moltmann, who is Hong Liang’s Doktorvater, is a key interlocutor for the two authors of the book, as they themselves make clear) before raising the question of the relation between the theme of “home” with the theme of “law,” both human and divine. This question is important insofar as it may help us reflect on the conflicts that occur between homes and within homes “as spaces of law.” For homes are not merely private, social, and material spaces: they are also legal spaces.

The sixth essay, by Chammah J. Kaunda, is an African, Pentecostal response articulated in light of the insights of a particular tradition known as Bemba theology (Zambia), which offers a rich cultural and theological interpretation of the notion of “home.” Kaunda invites us to ponder the kind of “homing” we are called to, and to imagine this as an everyday activity which is orientated toward “redeeming homes” in the face of injustice, violence and destruction, i.e. in the face of the “un-homing of homes.”

The final essay, by Brad East, raises several questions, after some words of praise for the boldness of the book, a boldness signaled by its subtitle. The first question concerns Christian interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures. East wonders whether the authors are too cautious when they wish to maintain Exodus’ “integrity of its own,” not just as a figurative anticipation of Christ. “Gentile Christian interpretation of Israel’s Scriptures is unavoidably and irreducibly ecclesial, spiritual, and christological,” he writes. The second question concerns the church, and the sacraments of baptism and Eucharist, all marginal topics in the book. East wonders why this is so. Finally, he asks about political involvement: is the “household of God” supposed (or called) to take part in political life, where the “old aeon” is all too visible? If yes, how is it supposed to do this?

We are fortunate to have this book. We can thank Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz for their contribution to theological reflection. And we now are fortunate to have these seven essays, written by such insightful scholars. Enjoy!

3.14.24 |

Response

A Transformation Narrative of an Indwelling Spirit

In a time of crisis, many people ask for a vision or a narrative to help them cope, understand, and guide their thinking and actions. When we look at our time, there are many crises in the world which lead to different levels of distress. The most relevant question then seems to be: What is our narrative for a time when faith, church, God, and the language of Christianity are often no longer understood as relevant? How can the good news of God’s love be articulated in our time?

Different times found different foci in their theological response to this question. In Luther’s time, justification by faith alone was lifting the yoke of religious fear. In a time of world wars, dialectical theology that proclaimed God in opposition to the misleading, even war-proclaiming culture of Christian nationalism gave freedom to faith, believing in God as the counterpart to and redeemer of this world.

In present times, it is quite brave to tell A Brief Story of Everything, since we tend to rather argue on specific theological problems instead of engaging with the whole. Volf and McAnnally-Linz decided to tell the Story of Everything as a story of homemaking: The Home of God. This is fascinating to read and easy to follow along. But this fine example of theologically and ethically engaged storytelling leaves me with a pressing question: How do we do theology and how do we tell our narrative? Since, as Barth would say, we start in theology with the Deus dixit in Jesus as witnessed in the Scripture and in the church, we have to wrestle with Scripture, the history of doctrine as well as with our reason as it is shaped in present times and as our questions are shaped by present challenges. The authors take up this challenge by telling a story informed by exegetical insight, a story of dogmatically informed belief interconnected with the theological claims of Luther, Augustine, Hegel, Tanner, and Moltmann (22–28).

So raising the question of method is not a critique of the book, but a question that emerges as I was reading it. Theology as narration of the Christian story is en vogue. In the German speaking realm Ralf Frisch recently read Karl Barth as a master storyteller. Ricœur told us how we grasp reality through narratives. Biblical scholars now work quite often with synchronic readings of the biblical narratives. However, reading a narrative dogmatics was a first for me. On less than 250 pages, it interweaves biblical witness, major theological loci, and themes from our present times into an encompassing tale of the world from beginning to end.

In spite of its brilliant execution, my remaining unease with this method concerns the authors’ claim not to propose a “theory of everything”, but rather to tell a “story of everything” with God as the principal author of that story (19). A theory can be prompted for its interconnectedness with other theories and the other sciences, and it would be under constant pressure to fill any gaps through more theorizing.

So what is the criterion for a convincing narrative? Of course, a story does not have to cover all topics and eventualities. How differently could we tell one story? Could we not tell the same story as a story of the temple or of the kingdom (10–11), and would one end up somewhere different, but no less true to the scriptural witness?

Even the three stories of the biblical books of Exodus, John’s Gospel, and Revelation retold in Home are all different versions of the same story. The authors claim that the latter are “both variations on the theme set by Exodus and a continuation of the same story” (26). For instance, the baptism in John is analogous to the exodus from Egypt as a delivery from slavery, and it is analogous to the exodus from Babylon in the book of Revelation (206).

Thus, The Home of God is a constructive approach to dogmatic storytelling. This approach struck me as most intriguing but also challenging, for the distinctive composition of the story as a whole implies certain theological claims, while its parts come across as exegetical claims or simply paraphrase. The mode of storytelling invites and inspires theological reflection, but it also complicates the dialogue with classical dogmatics.

In what follows, I try to look at the book’s main principle of home-making and then pick up one specific theme, the indwelling, home-taking Spirit, with regard to three dogmatic topics: faith, sin, and transformation.

The basic principle of the story is the meeting of God’s home and the human’s home on earth with Rev 21:3: “Behold, the home of God is among humans” (4). This picks up a strand of biblical imagery which alludes to a rich phenomenology of being at home and making a home. The story of God’s homemaking is told as a critique of our present time in order to evoke the longing for a different, better home of love (see 2). The main thesis is: “Christian faith actually offers a vision of a form of the world toward which we can joyfully direct our hopes and strivings. We argue that creation comes fully to itself when, indwelled by God, it becomes God’s home and creatures’ home in one” (2).

The image of being at home invites further exploration. What does it mean for a person to find a home in faith? How is the reality of our worldly homes with all its challenges (family, mortgage/economy, pollution to name few) altered by faith? And how does the aspect of redemption figure in establishing an oikos?

The story begins with the Exodus out of bondage in Egypt, i.e. with a move from the house of slavery into a people of God in the promised land. The authors tell us about God’s affectionate handling of the Israelites’ suffering (locus: theodicy). They tell us about the trust and faith required of the divinely-elected leader Moses as well as of the people of Israel (as condition and fruit of salvation; 41) to become God’s covenant-people (locus: faith). Thereby faith is directly dependent on the character of God who reveals God’s name and mercy (locus: doctrine of God; 42–47, 56–62). Here the authors introduce the dualism of oikos and dysoikos that will reappear often in the story: Egypt incorporates all dysoikic ways of living, whereas the promised land symbolizes the homelike life (48). Thus, the exodus becomes a story of liberation—even as the homecoming of the people of God is tied to living within the covenant-law that constitutes their home (51).

In the Gospel of John, God’s homecoming is told as the incarnation in a human body, instead of accompanying Israel through the tabernacle (74). The goal of the second part of the book is to explore this shift. God is now viewed as Father, Son/word, and Spirit (loci: the doctrine of the Trinity and the doctrine of the incarnation as true God and true human; 80–96). Jesus reveals God as love (101). In his death and resurrection, the themes of sin, forgiveness and new life are addressed (locus: doctrine of the cross; 110–23) and by Jesus’ resurrection a new worldly presence of Christ in the Spirit is introduced (122). Through faith, one becomes God’s child and a member of the divine household. This life in God’s oikos is mediated by the Spirit yet a voluntary decision for a life in the love of God and others (locus: the doctrine of the twofold law of love as new commandment; chap. 6).

In the final part, the whole story is retold from the vantage point of Revelation. Here, judgement and condemnation are discussed. The tension between God’s renewal and judgment for one’s deeds and sinful willing is solved by painting two alternative futures under the images of the dysoikos, i.e. Babylon, and the oikos, i.e. the New Jerusalem. The narrative arc ends with the “mutual indwelling of God and creation” on this renewed earth (212).

In this story of God and humans finding a home with one another, three interrelated topics stand out to me as especially interesting for further conversation:

- Faith is outlined as trust, assent, and will (136). In coming to faith, one needs all three and must enact them through one’s own capacities in the deepening journey of faith. At the same time, the authors describe faith as the gift of being born of the Spirit (141). However, in their analysis of faith as “seeing,” in John’s Gospel, the authors claim that “a person can commence a journey to receive Jesus” (144). This makes the aspects of election and grace seem less prominent. Here the emphasis on “the need for the reception of God by faith” (27) is especially telling, as it is raised against Tanner’s theory of Christ’s incorporation of the world. Reading along further, one continues to wonder whether the authors consciously avoid talking about grace or whether this is a result of reading John instead of Paul. Likewise, the Israelites’ acceptance of the covenant in Exodus, the “seeing” of faith (see 142-144; 186), and the indwelling Spirit are narrated in ways that often blur the lines between divine action and human deeds.

- According to the authors’ reading of John, sin is not the predominant problem solved by the incarnation (97). Though the book does not spare us the brutal reality of our world, it does not conceptualize it as sinful, rather it is rendered as the contrary to God’s home using the term dysoikic (17). Instead of reading the incarnation as a presupposition of salvation or as the world’s incorporation into Christ, it is conceived as a “dwelling among” (John 1:14) people, thereby bringing creation to its fulfillment (98). Thus, the lifestyle of Babylon is the dysoikic alternative to the New Jerusalem provided by God’s nearness. This modifies Luther’s strict distinction between gospel and law as well as inner and outer person (27).

In their storytelling of the cross, they follow the Johannine sayings about the lamb bearing sin and sins to give life, without giving a reason why the death on the cross was necessary other than stating that it was for forgiveness as a crucial part of homemaking (114, 117).

- The treatment of faith and sin leads me to my third question: what does the transformative power of faith consist in? Put differently: How are the present and the future connected in eschatology? Here the authors again introduce two agents without clarifying their interrelatedness: God giving abundantly (160) and the deed of the disciples (165). Both are tied together in God’s Spirit with the goal of a “transition from the dysoikic realities of the present world to the new world become God’s home” (171). Thereby the Spirit becomes central to the narrative, since the story of redemption does not target a transcendent reality but our present reality, as “Christ’s mission was to change this world” (128). Creation and new creation are tied together by the Spirit, who is “the life-giving Spirit of both the original and the new creation, affirming the first and giving them a foretaste of the second” (129). And it is through the Spirit that God dwells within believers and is with creation in order “to form God’s home” (135). However, the locus of transformation lies in the disciples, who were “transformed from mere recipients of God’s gifts to givers of gifts, God’s and their own in one” (165). Thus, the interim is a time for the church to pursue its mission of home-making by coloring the world with God’s love (164–68).

This again raises in my view the question of agency, which might be easier to tackle in a theory than in a story. What is the active role of the human? Similar to the interpretation of John, the readings of Exodus and Revelation remain ambiguous: “Both the departure from the world as it is (in Exodus, deliverance from Egypt) and the entry into the world become the home of God (in Exodus, God’s coming to dwell in the tabernacle) are God’s work, though humans are not mere passive beneficiaries but joyful participants” (206–7). It is stressed that the home of God “cannot simply be a human project” (208), rather, it is a gift for those who imitate Christ and remains a gift (208–9). But this again oscillates between a gift for the willingly receiving believers and one for humanity as such.

I would like to frame these questions regarding faith, sin, and transformation as an invitation to further unfold the core imagery of “home.” How do we make our home in the world when we are at once invited into God’s oikos and yet still living in the dysoikos of an imperfect world? What does sanctification in faith mean for human agency when God is “in and with” creation? How does the indwelling of the Spirit reflect an existence that finds itself simul iustus et peccator? Perhaps the existential experience of living in the polarity of grace and sin, nearness and concealment introduces a further dramatic arc into the story of God’s home and homemaking between the times.

3.21.24 |

Response

Salvation in the Form of Its Historical Opposites

The Home of God is a masterwork that represents a renewal of theology. Its authors dare to elaborate a systematic discourse that closely approximates biblical language. Many theologians today are seeking an exegetical theology, and Volf and McAnnally-Linz succeed in offering a model of the genre: the Book of Exodus serves as a matrix for the discussion of God’s dwelling with his people; the Gospel of John is the Christological and pneumatological condensation point; and the Book of Revelation symbolically anticipates the denouement of God’s dwelling with his entire creation. The unifying metaphor is that of the household, which is clearly distinguished from the dysfunctional homes we are too often familiar with. God wants to dwell not only with his people, but with every human being. This divine project of dwelling is the vector that unifies the great biblical narrative. Along the way, there is room for a constellation of households, which the authors avoid calling a city (I will come back to this point). At the end of the biblical adventure, God and the Lamb inhabit the new earth along with their people, and the whole earth becomes the Holy of Holies.

The rereading of Exodus here is particularly insightful and instructive, claiming that although Moses plays a special role, God establishes an unmediated covenant with his people. The Tabernacle represents the concrete anticipation of God’s plan to dwell among them. At the same time, the inclination towards apostasy is such that his people can never exist without forgiveness. The tensions characteristic of salvation history are decisive for the ongoing adventure of the covenant: between God’s absence and his presence; between the partiality (towards particulars) and the universality of his covenant; between the gift of the land and incessant wandering. The challenge of absence is met by the portable tabernacle that concretizes God’s way of walking with his people. The scandal of partiality leaves God’s sovereignty intact, but it also signals the universality willed by God, from Genesis, through the election of Abraham. The promise includes the possession of the land, but this remains the conduit for God’s presence among humans. Exodus sharpens expectations and outlines a future to come. The fulcrum of this long story is, according to the Gospel of John, Christ Jesus, who responds point by point to Exodus, intensifying the paradoxes between particularity and universality, absence and presence.

The authors’ rereading of Revelation paints a fascinating picture of the final state of renewed creation, in which the old creation is led by God to its ultimate truth. The earth itself is destined to become God’s home among human beings. Moreover, like the first creation, the new creation is a gift. Humans cannot bring it about through historical millennialism. Here, worship, politics, and economics attain their definitive truth: Culturally, in the New Jerusalem, all humans are high priests. They enter and live in the Holy of Holies; the whole city is a temple of earthly dimensions. Mutual inhabitation no longer occurs solely between God and his people, but between God and the whole of creation. Politically, all people reign with God and the Lamb. The throne is now accessible to everyone, and everyone receives a new and unique name, which demonstrates the impossibility of manipulation. Economically, the new city is endowed with the wondrous features of a garden. The river of life fertilizes the earth and everyone receives life also for the sake of others. Work regains its original meaning: plowing and tending become concrete acts of praise and gratitude. Wealth is now measured by what really counts; accumulation is no longer tallied up. Finally, matter itself is transparent to the glory of God, which shines in all things. The presence of God ennobles physical creation: the whole of creation becomes the Burning Bush that is not consumed. All people are within the manifestation of God. To enjoy creatures inhabited and transfigured by God is simultaneously to enjoy God, but not God alone.

Volf and McAnnally-Linz’s book is edifying in both its theological style and its doctrinal content. In honor of the powerful challenge presented by this masterwork, I will first sketch the book’s method and call it into question from a specific angle, before revisiting one aspect of the work’s content, namely the ambiguous metaphor of the city.

The authors’ project of elaborating a systematic theology in the biblical vein is convincing. That said, it is not free from confessional presuppositions. For example, the insistence on the dialectic of absence and presence, even at the time of the incarnation, as well as the assertion that God’s glory is perceptible only in the humiliated flesh of Christ, are important motifs in the Lutheran tradition. A circularity between the interpretation of Scripture and a specific faith tradition is thus operative in this work, as in any theology that is not a mere exercise of pure reason. However, the main challenge of an exegetical theology seems to me to lie elsewhere: How can we elaborate a discourse that is accessible to our contemporaries, including outside our confessional circles, by adopting a language as specific as that of Exodus and the Gospel of John? The closer a theology remains to the biblical witness, the greater its semantic and soteriological richness. However, it loses its relevance for potential listeners who have not been molded by this same biblical language. This is why anthropological mediations of faith are necessary to make explicit the universal message of the biblical witness. For example, the dialectic between particularity and universality, which plays out fully in Exodus and the Gospel of John, speaks to a widely shared anthropological and cultural challenge: In what form is the universal accessible and at what cost? Is a passage or detour through particularity indispensable for a universal proposal to be credible? Is the partiality of an elective love the only possible demonstration of a love ultimately extended to all? This is the basic logic of election: It is because God chose Abraham with a view to blessing—from near and dear—all of humanity that God’s love became credible in its universal aim. If God had simply said to humanity as a collective, “I love you,” no one would have been moved by such a general revelation. Articulating these kinds of questions reveals the relevance of the biblical witness. Salvation history encounters the divided humanity of Babel, which either doubts the universal or seeks it in oppressive ways. The Jewish tradition and the Christian faith offer a singular response to a challenge of common humanity subjected to conflicting particularisms. The subtitle of Volf and McAnnally-Linz’s work, “A Brief Story of Everything,” signals their ambition to make a universal statement. However, the necessary elucidation of the anthropological register underlying this theological project is missing at points.

As for the book’s content, the integrating power of the metaphor of the household is remarkable. The household is well established as the semantic focal point from the beginning. But while I am convinced by the authors’ proposal, I am puzzled that they hardly exploit the image of the city, which incorporates a multiplicity of related households. Yet the New Jerusalem is a city. This deserves special attention. The biblical history of cities is fraught with ambiguity and sin. The first builder of a city is Enoch, son of Cain (Gen 4:17). Cities soon become synonymous with excess, exaltation, and oppression, with the mad project of Babel—a city with a tower, both under construction and unfinished (Gen 11:1–9). The biblical city often resembles a political deformation of the household, a dysoikos (dysfunctional home) in the terminology of Volf and McAnnally-Linz. They devote a chapter to the Babylon of Revelation. Notwithstanding the disastrous genealogy of human cities, at the end of the great biblical narrative, a new and holy city descends from Heaven. The definitive form of salvation thus appropriates a major deviation in human history: the human project of cities. Similarly, God’s reign appropriates a human history of kingship, which was originally a divine concession to the desire to align with the dysfunctional politics of the nations surrounding the chosen people (1 Sam 8). God thus gives salvation through concrete forms that are marked by a history of deviation and sin. “Make not the house of my Father a house of traffic,” Jesus warns the sellers in the temple (John 2:16). The city, the temple, and the throne have been misappropriated, overexploited, and deformed. God, however, takes up the side roads followed by humanity and by his people: A city descends from Heaven and is wholly a temple. God and the Lamb share the throne, and the elect of all nations now reign alongside them. God’s dwelling place takes on the stigma of human history and religious institutions. These are transfigured and sanctified, but still recognizable. For us, salvation comes in the form of a conversion of these ambiguous realities, and even of its historical opposites: a city-temple and a throne. Only God knows how to accomplish such things.

3.28.24 |

Response

A Theology of Worldliness

On every page of The Home of God, Volf and McAnnally-Linz gift us with a theology for the world, a theology of worldly character, a theology of the worldly and not of the otherworldly. Their theology is one in which this world is becoming God’s true home. It is one in which incarnation “underscores the significance of the home’s materiality and shows that the presence of God in the world in no way detracts from its worldliness but brings the world in its worldliness to fulfillment” (90). It is a theology in which our end is good work in the world that is God’s home, wherein “All that remains is thirsting after more of just that world—more of God and the world in their distinction and unity—and therefore maintaining and enhancing it” (219).

Just this worldliness, I believe, is a vital center of Christian theology because it is so deeply about Jesus, and so, the book opens us to much needed possibilities for theological imagination and the embodiment thereof. Below, I’ll ask some questions about the book in two categories, the first about the book’s claim to narrating the story of everything and the second, related, category, about the nature of the worldliness and the home that we are speaking of and how we might explore further implications of the world as God’s home. As I ask these questions, my doing so is located firmly in the context of my appreciation for the book’s call to worldliness.

Everything

Wolf and McAnnally-Linz insist that they’re telling us the story of “everything” and center that insistence on the image of “home” and of God’s coming to share a home with us as the right image for that everything. They argue, for example, for a shift from temple metaphors to home metaphors as a way of including more of “everything” within our theological accounts. Similarly, they reject “kingdom” as central metaphor “partly because not all of life is politics and partly because the politics evoked by the metaphor of kingdom runs counter to the politics of the New Jerusalem” (11).

I’m puzzled. While persuaded that attending to the right metaphors and imagining those metaphors rightly is a great deal of the theological task, I’m unconvinced of the need for “the” right metaphor, as opposed to many right metaphors, and, if Wolf and McAnnally-Linz want to dig in there, I’d like to hear a great deal more from them about why. Scripture piles metaphor on metaphor in helping us to know God, allowing the metaphors to dizzy us into glimpsing the dazzling otherness of God.

Consider the quote, above, about passing over the metaphor of kingdom; “because not all of life is politics” and “because the politics evoked by the metaphor of kingdom runs counter to the politics of the New Jerusalem” (11). I suppose these two objections to “kingdom” contain a lot of truth, but that truth seems to apply to any metaphor. Surely home, too, cannot describe “all of life,” nor does the metaphor automatically evoke holy, healthy biblical resonances. We’re sinners immersed in a world of sin, and all our metaphors evoke things that “run counter” to the vision of holiness and health revealed to us in Jesus Christ. Volf and McAnnally-Linz are clear about the sinful resonances we may attach to home and coin the word dysoikos to name the harms of home, the “parodic sinful distortion of home,” (15) and the characteristic forms that distortion too often takes. So, home, like kingdom, requires relearning, reimagining, if we are to seek faithfulness. All our metaphors need both exorcism and sanctification if they are to help us speak truly of God and live well together.

My puzzlement over the insistence on one metaphor extends into the book’s method, which Volf and McAnnally-Linz intend to be primarily a reading of Scripture, specifically, in this volume, a reading of “home” in Exodus, John, and Revelation. “We discern God’s character best,” they tell us, “by observing what God does within the story of everything” (43). I, too, see Scripture as the center of the story of everything and am interested in paying attention to God’s character revealed in that story; the method sought by Volf and McAnnally-Linz is a delight; may such readings multiply!

Still, a volume of this size cannot, of course, try to closely read the whole of Scripture, requiring the choice of the three books named. Assuming those books were chosen because they’re helpful for unfolding the reading of “home” provided, we readers may want to know how that reading would change were three other books chosen. Is “home” as persuasive a metaphor if we read Leviticus, Mark, and Hebrews, or might “temple” again make a stronger appeal? And, while it is always refreshing to see theology focus elsewhere than on Paul, we theologians can’t leave him alone, and his corpus might press other metaphors again. Where does cross, for instance, fit with home? I have no objection to a theology centered on “home;” in fact, I rather love it, but I’d like to hear more from Volf and McAnnally-Linz on their insistence on singularity here, and, more generally, on how they’re thinking about hermeneutics.

What kind of worldliness? What matters about home?

At the beginning of the volume Volf and McAnnally-Linz do some work in defining what home is and what matters about it. For instance, home, we’re told, includes relations, resonance, attachment, belonging, and mutuality (14). And, as noted above, they’re aware of the ways home can be twisted, of the harms of home they name as dysoikos. My questions, here, are mostly about wanting more about what home means, more about home gone wrong, and more about the kind of worldliness the metaphor “home” invites us to embrace.

As woven through several strands of feminist thought, the idea of “home” invites us to think about women, about the Kinder, Küche, Kirche of it all. It invites us to think about children, and meals, and gardens, and who does the dishes and cleans the toilets (vital aspects of the work Volf and McAnnally-Linz point to with eschatological longing), and it invites us to worry about and rise up for justice over the ways “home” can cover so many sins in precisely this realm. I kept waiting for the book to get there, excited to see how it would play out, but it didn’t do so. It’s silly to criticize anything for not including one’s own pet interests, but I do think the theme of home begs, here, for more outright feminism and for more attention to aspects of worldliness that have so often been the realm of women.

While Volf and McAnnally-Linz attend to dysoikos, their rejection of the “kingdom” metaphor for the reason that “the politics evoked by the metaphor of kingdom runs counter to the politics of the New Jerusalem,” suggests to me that they still under-attend to those harms of home. Among those harms, they note, especially, slavery and violence, which are important, but most of the account assumes that we’re capable of living “home” fairly well, though the authors know how incapable we are of living the kingdom rightly.

Perhaps it’s too easy to forget that domestic matters are political (“the personal is political,” as some of those feminists would have it), that violence and slavery are explicitly linked to gender, race, and class in ways that poison our homes. Maybe all of life is politics, after all. When the New Testament talks about the family in the home, it remembers this, working into those household codes explicit protections for women, slaves, and children. How does the dysoikos that so damages our homes vary along with culture and context? In North America, we’re so used to thinking about home in terms of the self-sufficient nuclear family, for instance, though that context is foreign to Scripture. Or, to bring matters closer to my own home, in Chicago, how can we theologize home without also theologizing redlining and, long before that, colonialism? I’d love to hear Volf and McAnnally-Linz begin to unfold some of this.

More positively, it strikes me that there’s plenty of opportunity here to provide a further account of home as it relates to the Spirit and the church, to account for homemaking as church-making, after Jesus’s ascension, as we think about the presence of God, at home right here, with us. I think of Luther, one of the figures Volf and McAnnally-Linz name as key for their thought, and his tender attention to the vocation of home and hearth. I think of the art of homemaking, and the men and women who devote love and care to recipes and hospitality and coziness. I wonder about life in the household, and what it has to do with joy, obedience, and mission, and I turn over knotty questions about the boundaries of home: how to be hospitable while also offering the protection home must offer to those who belong there.

I think of kinship and family. How does “home,” as the center of the story of God’s presence, help us to imagine our relationships aright, to those who are blood and those who are not? What does it mean that new birth and adoption—both home and family metaphors—sit at the center of the story of salvation? I think of babies and small children and the sick and the old. I think of the way the New Testament relativizes biological family and babies in favor of the family of the church and evangelism and the fruits of the Spirit. I think of the table as the center of the home and of what it means to feed, to nourish, across years, and of the Lord’s table and the wedding supper of the Lamb. And I wonder, how do these matters matter to the God who makes a home among us? I’m not suggesting Volf and McAnnally-Linz should have answered all these questions, but they are questions their book excites for me, questions it would be lovely to discuss with them, over a cup of tea. I’m grateful for the book and look forward to continued conversations about what it means for God to make a home among us.

4.4.24 |

Response

Does the “Home of homes” need a “law of laws”?

Some preliminary thoughts on The Home of God

We are at a turning point in history. The current conflict and disorientation on the political, economic and ecological level worldwide confronts us with the fundamental question of whether humans as one species can still deal peacefully among ourselves and share this great planet with other living creatures. In their new book The Home of God (2022) Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz approach this question with a “systematically unsystematic” (3) theology of life. This theology focuses on the theological interpretation of home as an “image” (4) of God’s successive home-making works in his creation and the transformation of the world that results from this.

According to the two authors there are three great narratives of home in Western history: the Odyssean narrative, the prodigal narrative, and the Abrahamic narrative. Unlike the Odyssey narrative, which is characterized by its emphasis on the plurality of homes and their potential conflict with each other, the prodigal narrative highlights the universality of home. In contrast to these two narratives, the Abrahamic narrative is based on a concept of the promise of God. This promise makes possible a concept of home that integrates particularity and universality and thus becomes the “home of homes” (175): “Homes nested within a series of broader contexts that are themselves homes and at home with one another” (176).

Volf and McAnnally-Linz argue that the “home of homes,” based on the concept of the Promised Land and the mediating role of God of Abraham between humans and the land, overcomes the “abstract cosmopolitanism” (175) of the prodigal narrative on the one hand, and the “agonistic pluralism” (175) embedded in the Odyssean narrative on the other. To avoid making this concept a vague utopia, they highlight the damage home can cause, such as violence, from a realist perspective and name this potential harm as an “un-homing power” (74) rooted in sin, the dysoikos. As the authors emphasize, the “home of homes” is an eschatological vision that deals with the present state of the world “in the grip of sin” (74) and, more importantly, with its final transformation towards the new heaven and earth.

In its essence, the “home of homes” can be seen as a positive theological vision based on a theology of life. In response to a world currently struggling between globalization and de-globalization, between war and peace, it seeks to offer a promise-based, dynamic, and God-centered reconstruction of global solidarity that begins with the transition of our daily “life in the middle” (229). In this concept of home, which I greatly appreciate, I sense the profound influence of Jürgen Moltmann’s messianic theology of eschatological hope. Indeed, the authors note themselves that Moltmann would be one of the five key interlocutors of their book, and “in spirit and content, the theology in this book is closest to his” (27). Since both Professor Volf and I completed our doctoral studies with Moltmann and still benefit from the theological tradition our “Doktorvater” initiated, I would like first to sketch the theoretical relations, which I discern between The Home of God and some of Moltmann’s central ideas. In a second step, I shall then venture a more critical response to the concept of a “home of homes.”

2.

The Exodus tradition, which documents the cultural memory of Israel’s liberation from Egypt, occupies a central place in Moltmann’s landmark book, the Theology of Hope (1964). The Exodus provides Moltmann with a grand theological narrative to address God’s liberating historical action from a God-centered perspective. The Home of God carries on this Exodus tradition and creatively transforms the classical tension between Egypt and the Promised Land into a tension between “dysoikos” and the “true home in both its material and social dimension” (51), which is related to our current situation.

Another of Moltmann’s core ideas is the eschatological presence of God in his creation. This presence expresses itself in his concept of shekinah that he derives from the Jewish tradition. In his books God in Creation (1985)1 and for The Coming of God (1995)2 the idea of God’s eschatological presence plays a fundamental role. It deepens the promise-based covenantal partnership between God and the created world and opens the cosmological dimension of the covenant. In a similar vein, The Home of God draws on the idea of God’s coming and presence in the world for its theological interpretation of Scripture. The promise and covenant in Exodus, the incarnation in John’s Gospel, and the eschatological vision of the new heaven and new earth in Revelation become different stages of God’s home-making actions in the created world. The concept of “home of homes” thus concretizes and illustrates God’s faithfulness to his covenantal partners, which Moltmann expresses through the concept of shekinah.

A key feature of Moltmann’s theology of hope is that it interprets hope through the interactivity of the covenantal relationship between God and the created world. Within the framework of the covenant, hope implies not only humans’ promise-based hope in God, but also God’s trust-based hope in humankind. We find here the theological nucleus that allows Moltmann to transform his theology of hope into an ethics of hope in his later work.3 Again, we find a systematical relation in The Home of God. Volf and McAnnally-Linz clearly note that the covenant-theological tradition corresponds to humanity’s home-making actions in the world, the former providing moral orientation and inspiration for the latter, which is to be an analogy to the former. This correspondence is necessary because “God cannot simply make the world into home, bypassing free human agency” (192). In this sense, the “home of homes,” which integrates the plurality, particularity, and universality of home, can also be interpreted as a basic moral guideline for the home-making actions of human beings. It leads us to “reconcile with one another, and actively and joyfully live in home-constituting relations” (193).

The concept of the “home of homes” is enlightening and deserves to be further explored and developed. In particular, I am interested how law relates to this concept, whether the “home of homes” alone is sufficient to balance plurality and universality, or whether it needs to be complemented by a theological concept of a “law of laws”? The “law of laws” means that there is a need for “a certain kind of order” in every community of life, and that every order contains “the assignment of responsibilities and the distribution of benefits” (11). Further, such order implies a quest for justice; not a justice that imposes itself top-down through a hierarchical structure, but a justice that reaches out to the whole of creation, including humans and other creatures on this planet and beyond. If we follow the theoretical tradition since the Reformation regarding the dialectical relationship between the gospel and the law, then it can be said that the “home of homes” embodies the gospel side of God’s home-making actions in the world, and, correspondingly, the “law of laws” would address its legal side.

To be sure, The Home of God does not ignore the significance of law. On the contrary, the authors focus on the legal content of the covenant, the legal meaning of the Ten Commandments, the new law implied by the Incarnation, that is, love, and even their discussion of violence in the eschatological context represented by the vision of the lion leaves room for exploring the question of law. What is clear, however, is that their interpretation of the law follows a Pauline historical-theological model, focusing more on the transformation from the old law to the new law, and on the summation of love for the law. From the perspective of a “law of laws,” the universality of law is powerfully expounded here, but the plurality and particularity of laws, which correspond to the plurality and particularity of homes, seem not yet sufficiently addressed. The plurality of laws, however, is crucial for the establishment of a realistic relationship between homes with “boundaries” (175), if they do not want to be forever bound in “agonistic pluralism.” One of the most central issues for the concept of the “home of homes,” it seems to me, is how to deal with the conflicts between homes as spaces of law.

A home represents not only “a social and material space” (11), but also a legal space.4 Thus, the plurality and particularity of homes will inevitably be reflected in a plurality and particularity of laws. At the same time, homes which are different from each other share the same home of the created world, and accordingly, particular laws in pursuit of justice are necessarily related to the inclusive justice for the whole creation. However, because of sin, conflict between the laws is inevitable, and as Moltmann pointed out in his classic work The Crucified God (1972), not only did Jewish and Roman law conflict with each other, but even the incarnate Christ, who was the embodiment of the new law, died in conflict with both.5 The concept of the “home of homes” clearly has the ultimate reconciliation as its goal, but my question is, what does this eschatological, universal reconciliation mean for the plurality of homes in the existing world? According to the authors, the moral imperative of the “home of homes” highlights God’s mediating role between humanity and the land, guiding human beings to reconcile with one another and live in peace, whereas the “law of laws,” in my opinion, deals with the norm of reconciliation and the implemention of divine justice in the midst of conflict.

In sum, The Home of God is a thought-provoking attempt to provide a biblical theological narrative of God’s home-coming actions to counter the alienation of home in the present world. To take his further, I suggest that God’s home-coming actions also contains the dimension of God’s legislation and justice. This legal dimension relates to the laws of the various communities of life on this planet, and it is necessary to present this dimension theologically, especially considering the plurality and conflict among homes in the world we inhabit. An all-embracing theological vision is only compelling if it integrates also this dimension.

Jürgen Moltmann, God in Creation: A New Theology of Creation and the Spirit of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993).↩

Jürgen Moltmann, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004).↩

Jürgen Moltmann, Ethics of Hope (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012).↩

I find Hannah Arendt’s articulation of this issue to be the most illuminating among twentieth-century political theorists. In order to argue for the legitimacy of Israel’s right to judge in the Eichmann trial, she used Israel as a mode for a new interpretation of the traditional concept of territory, “home” for a particular political community, which, in her view, is “that inevitably arises between the members of a group when they are bound together in millennia-old relationships of a linguistic, religious, and historical nature that have also been reflected in customs and laws that protect them against the outside world and differentiate them from one another. Such relationships become spatially manifest in that they themselves constitute the space within which the various individuals of the group relate to and interact with each other.” Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen, Münich/Zürich: Piper Verlag, 12th ed. 2015, 384.↩

Jürgen Moltmann, Der gekreuzigte Gott. Das Kreuz Christi als Grund und Kritik christlicher Theologie, Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlag, 2016, 119–46.↩

4.11.24 |

Response

The Home as a Theo-Biblical Category

Thinking “The Home of God” from Africa

The Home of God: A Brief Story of Everything is provocative, dynamic, paradigmatic, exceptionally crafted, brilliantly paced, and lucidly articulated. It powerfully reminds us that, in a world described as in the middle of a polycrisis, religion, Christianity in particular, has a vision, a framework for the flourishing of all things. The book is weaved with grace. It articulates the idea of “home” as a site of an entangled difference, as being at home in difference; it entails a multiplicity of images. The book offers a new way of thinking that opens up western theology to the plurality of ideas of homes and homing/returns which classical thinking tended or tends to overlook.

All this is to say that I deeply appreciated reading The Home of God, not just as a theologian, a Pentecostal Christian, but more so as a human first, before being an African—an identity perpetually located on the underside of global modernity, the most excruciating way of experiencing and encountering the “home” produced by global coloniality of knowledge, culture, existence and the very idea of home. The authors take the Home of God or God’s Home1 as a metaphorical approach to give an “unsystematic-systematic theological” unveiling of a continuum of history that intertwines the past, the present and the future in the interpretation of the story of everything. The authors take a globally sensitive reading of the Old Testament, particularly Exodus, to demonstrate the significance and the evolution of the idea of home through John’s Gospel to construct a vision of “God Coming Home.”

All this takes us to the opening words of the book, “No keen observation is required to see that something is amiss in the world. More than something—many things. That much is obvious.”2 The “abiding out-of-jointness to things” is, perhaps, an invitation to “carefully discern” the “texture of [human] dislocation—here and now.”3 This is a radical invitation to go back to the drawing board to wrestle with the web of knowledge that conditions human existence, and determine its actual meaning to remap the mindset or re-mind the human mind. To achieve this mammoth theo-biblical task, the authors reimagine, reconceptualize, and theorize “home and homefulness (longing for home). Home is conceived both literally and metaphorically as “a complex web of relations,”4 as a “primary site of integral human life”—“bounded material, social, and personal space of resonant and reciprocal belonging that is at its best when it is situated in a homelike relation to all other spaces on the great ‘home’ that is our planet.”5

In what follows I specifically focus on the idea of “the Home of God” as a political, socio-cultural terrain of webs of ambiguity, paradox, with multiple intersecting constructions, as a search for meaning and struggle to maintain the intricate balance of vital forces. I approach this from an African (Bemba) Pentecostal theological perspective because, as the authors argue, what is at stake in the world today is not merely the ideas of home, but the kind of ideas that could empower humanity to respond paradigmatically to the present conditions of the home. What I have in mind is the eschatology of the here and now or of the moment. This also means, as the authors observe, that the ontological, epistemological and praxeological idea of the home cannot be considered under a single category or defined universally, because in the worldview of the Bemba of Zambia, the Home of God does not exist as a separate substance from God. For God (Kwa Lesa) is Home Itself and the spirituality/vital breath that animates all vital homes. The Home (Imbusa) is the creative, originative and regenerative site of inter-indwelling and mutual participation of all vital beings and nonbeings. Imbusa loosely translates to ‘womb’ in English, yet its essence extends far beyond mere physicality. It serves as the creative and sacred site where the mystical union of God and creation unfolds, embodying the inclusive totality of spirituality and the profound wholeness of life. The inhabitants of Imbusa, whether beings or non-beings, possess no independent life; rather, they inter-indwell and participate in the Home. They are a kind of functional ritual material exemplification of some aspects of the Divine Home. All creation could be said to be a set of micro-ritual manifestations of the Cosmic Home. They represent the myriad manifestations and inhabitants of the One Home—God, each serving as a unique reflection within the unified whole. In this sense, Ubuntu as a key principle of the Home is not a homogenizing, but a harmonizing or a maintaining of the vital equilibrium of the Cosmic Home’s multiplicity of expressions.

In this context, “home” has an ontological diasporic condition: the flickering multiplicity of homes perichoretically intra-dwelling and participating in each other in an ongoing, often chaotic flux and reflux, an assemblage of vital forces into the One Home. Here we are not dealing with a smooth ontology or a linear progression of time and events, but with a paradoxical ontology. Hence, we might appreciate Martin Heidegger’s insight that every temporal disclosure in the symbolic order is always already an infinite concealment.6 The ultimate Home to be realized by the home is always already infinitely realized in Itself. This also means that divinity is always already “manifested-unmanifested” in the temporal natalities of homes. Humanity, like all vital forces, is not merely being-in-the-world, it is being-the-world and becoming-that-very-world, or rather, becoming the Home itself. This homing capacity is the source of narratives, cultures, values, lifestyles, belief systems, and ways of interacting with God and all things.

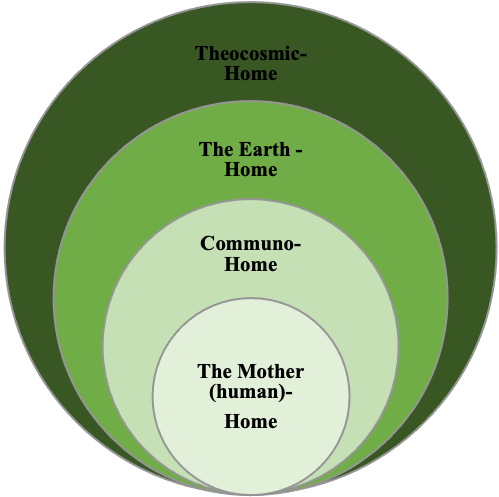

Therefore, the Cosmic Home represents all the critical knowledge, moral practices, and spirituality that form the vital homes. Bemba theology of the home is articulated at four-level as demonstrated in the diagram below.

As the diagram shows, in this home (imbusa)-centric ontology, all creation participates in the homing of life—Lesa. The All-thing is Home. Lesa (Bemba perception and conception of God) is the ultimate Home/Imbusa (par excellence). The earth, the community and the mother are microcosmic wombs/homes. The Home subsists in the homes. It is the singular plurality of life of the Home which animates the vital homes. The Home is the exception that is immanent to all finite homes “and thus,” in the words of Alenka Zupancic, “introduces an opening to the finite, makes [them] not-all, makes [them] infinite. Here, we are in the infinite.”7 In other words, they are marked by intrinsic non-allness, incompleteness, and permanently rocking their destiny in the Home. They are “rooted” in the abyss of divine possibilization which is the active principle of renewal and becoming; “the substance that constitutes of freedom, the capacity to begin.”8

In symbolic terms, the human home, often represented by the mother figure, is seen as more than just a place for gestation. It is conceived as the focal point for the creation, nurturing, and flourishing of life in all its multifaceted aspects. Each vital home is a liminal (ritual) space of becoming through an incessant assemblage of other vital homes and participation in the Cosmic Home. The earth home, communal home, and maternal home are not given but constructed, not determined but contingent. They are mobile, dynamic, reversible, and becoming. Therefore, the home can be un-homed. The un-home-ing seems to be the main characteristic of contemporary reality. All finite homes have the ultimate source of their intrinsic possibility in the Home which is also the possibilizing capacity of becoming. They are complex sites of performative/functional entanglement and actualizations of meshwork interconnected and interconnecting forces of life. Hence, it is within the symbolic home, the material home which the Bemba people create the family shrine—called Maternal Breath. This is an intense site of interaction and encountering of one another, the ancestors, yet-to-be-born, and other living and spiritual forces. The maternal home is understood as a socio-relational practice of life, encompassing more than just physical space but also the intricate web of social, intellectual, mental, spiritual and emotional relationships that nurture and sustain life. Similarly, the earth home is seen as an ecosystem where diverse forms of life coexist, each contributing to the richness and inclusivity of the divine presence within the concept of Home/Imbusa. Both the maternal home and the earth home symbolize the multiplicity and inclusive diversity inherent in the manifestation of the Divine Home, emphasizing the interconnectedness and interdependence of all aspects of existence.

It is the Home that creates the homes. Hence, liminality is the condition of the home. In short, a home is an event of becoming. It is not a noun but a verb. It is what communities and families do. In reality, the idea of home-ing and homing is not just something reserved for humanity; instead, it is an intrinsic aspect that creation is inherently predisposed to manifest. The idea of “homing” implies a continual process of seeking and returning to God, the ultimate Home of all things, reflecting the inherent desire of creation to find its ultimate fulfillment and unity within God. This inherent capacity for homing, along with the quality of homeness, collectively shape and characterize the fundamental identity of all things. By implication, the idea of “God as the Home Itself” is not reduceable to any monolithic category; it is dynamic, fluid, a liminal space of constructions, negotiations and interactions.9 Life is a ritual of rituals; the cosmos is a home of homes, and God is the Cosmic Home of homes. Homeness is an attribute of God. God is an eternal Home to Godself and all creation. To argue that homeness is an attribute of God suggests that the essence of being at home, of belonging and comfort, is inherent to the Trinitarian nature. This concept implies that the Trinity embodies a sense of perichoretic familiarity, security, unconditional love, and fulfillment, akin to the feeling of being in the Trinity as their own Home. It underscores the idea that within the Trinity, there is a profound sense of unconditional acceptance, belonging, and peace, which transcends physical spaces and extends to all aspects of existence. If we dare to boldly suggest that each member of the Triune God is the Home of the other members, we can also correlate that creation is meant to mirror this Trinitarian structure. This implies that everything serves as a home for everything else within the vast multiplicity of differences. Thus, the concept of home transcends its traditional bounds and becomes a metaphor for the entirety of existence.

There is no dichotomy, and there are no confusions in the inherent relationships between the spiritual and the secular, the living and the dead, humanity and other forms of creation, the cosmos and God, and so on. For example, ancestors are regarded as having the ability to manifest themselves through various media, such as natural elements or masquerades. Individuals who believe in these manifestations do not perceive a fundamental division or experience confusion between the ancestor being manifested and the medium through which the manifestation occurs. This implies that those who hold these beliefs see a seamless connection between the spiritual realm and the physical world, where the spiritual presence can manifest itself through diverse forms without creating any significant contradiction or uncertainty for them. In other words, the Bemba philosophy of ubuntu (interpreted from a matricentric perspective) does not subscribe to conflicts or ambiguities in the fundamental connective interactions between various aspects of existence. It upholds a unified and radical view of life, ultimately one that permeates and animates all things. In this perspective, all things participate in this singular life, and since nothing exists outside or above the only life that encompasses all things, nothing can be said to be in opposition or contradiction. Instead, all things are vitally interconnected and can intra-exist harmoniously without creating confusion or conflict. It could be argued that God is the Home in the multiplicity of homes which arise within God the Home of all things.

Here the question arises: how does this help us make sense of the idea of the home in an African Pentecostal theology? African Pentecostalism perceives creation as vulnerable potentiality, as radically open to newness and becoming through the processes of fragilities, instabilities, consistencies, volatilities, and mutual creativities. It understands God and creation as mutually concealed within the mysteries of God. Hence, the Pentecostal position entertains “the idea of radical openness to God”10 and God’s economy in creation, which involves doing something impossible or otherwise new. No circle is closed in Pentecostalism; rather, the between encounters and interactions are ever-open spaces of porosity-permeabilities. Pentecostal courage is grounded in the willingness to recognize the strangeness or the mystery at work in the universe, to seek to discern the Spirit working in them. This discernment suggests an openness to the unexpected, to the seemingly impossible or incredible ways in which reality enfolds and unfolds within the mystery of God in creation, and creation in God through Christ—the redemptive home in which God lives “and through [Christ] that God reconciled everything to” God (2 Cor. 5:19-23). Thus, the essence of African Pentecostal thought consists of incarnation possibilities, multiplicity, natality, and liminality as the bedrock for interpreting and encountering God as the God of otherwise-new things, who relates with reality in mysterious ways. Harvey Cox rightly describes Pentecostalism “as the rediscovery of the sacred in the immanent, the spiritual within” the material.11

Since African Pentecostalism interprets and articulates reality through an African religio-cultural framework that tends to also emphasize incarnation from rituality. In this system of thought, the secret of God as the Home in relation to creation and creation as a home in relation to God is exemplified in the idea of incarnation. Incarnation is first and foremost God’s revelation in creation. Arguably, God’s revelation is not for God’s sake. God does not need a revelation. God is the Revelation Itself. It is for humans’ sake to make sense of themselves and of their place in God the Home of creation, i.e. within creation. The incarnation is a revelation of the divine enigma veiled within the material reality. It unveils the endless possibilities for interpreting how God interacts with the material world. Revelation suggests that creation must realize the revealed incarnational potentiality as itself in God. Everything that is revealed to humanity is for the sake of human becoming and the flourishing of all creation. The incarnation has nothing to do with the trauma of figuring out God, but rather with the fact/goal of trans-figuring creation itself as constitutive of active home potential for becoming and realizing abundant life for all. The incarnation has imperative practical implications for homing and home-ing all things. It has ritualistic dimensions of perichoretic inter-dwelling and mutually bounded, entangled participation through maintaining the equilibrium of different vital natures (homes) without confusion, without division, and without separation in radical mutual homing. The incarnation reveals both the autonomous agency of God and creation. God is the eternal Home, the ultimate source of belonging, stability, flourishing and fulfillment within which creation finds its constant state of homing and home-ing reality. Therefore, Christ’s incarnation is paradigmatic for thinking of the home and homing as ongoing ubuntu-carnations. This way of thinking overcomes the exclusive separation between God’s home and God as the home. God lives in creation; creation lives in God. This should be understood within the Chalcedonian hypostatic principle. However, one may concede that the idea of mutual and mystical inter-dwelling, where God is the eternal Home and creation is a constant process of ‘homing/returning,’ resonates with the mysticism of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, particularly the idea of coincidentia oppositorum.

This also suggests that if we think of homing as an everyday activity of redeeming homes, God’s incarnational dwelling in them is an ongoing divine resistance against injustice and the destructive un-home-ing of homes. The divine resistance against un-home-ing is exemplified in the perennial incarnation as a gracious divine indwelling of and a being-indwelt by ontologically inhomables that define reality today. This functional ontological agapetic/agapeic indwelling suggests that God’s endless promise of love, faithfulness and justice will be fulfilled in the singular-plural inter-dwelling of difference. There is no individual or community, singular or plural, local or universal, only “we-who-are-not-the-same-but-the body-of-Christ-is-us-all-and-in-us-all.”12 The fullness of Christ is in me, and the fullness of all things that are in Christ, including me, is in me. “I am the totality of all that is and or in Christ—Christ-in-me-I-in-Christ-Christ-in-God-God-in-Christ-I-in-God-everything-in-Christ-I-in-everything-and-everything-in-me: Home-is-all, all-is-Home.”

Thus, we can talk of the intra-home—a form of deep home-ing that can only be achieved through vital intersubjective homing–participation. This is exemplified through the revelation of the incarnation of life in Christ (Home) — “becoming new humanity in Christ” (Eph. 2:15), “new creation in Christ” (2 Cor. 5:17). Deep homing/returning is a moral-political imagination or a kind of politics of planetary action embedded in an anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-patriarchy, in a post-anthropocentric and post-dualist critical vital solidarity grounded in the quest for everyday inter and intra-carnations of difference in which all lives matter. Indeed, the ongoing global consciousness of the polycrisis, the emergence of posthumanist thought, the awareness of the superhuman intelligent capacity of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the ongoing rediscovery of the eco-relationality or of the ecological liberation potential of indigenous philosophical systems have set into an irreversible motion a new cosmic vision of the future. This new vision, if it is not disorientated by equally emerging necropolitical or rather necrocosmic forces, is likely to give rise to new forms of co-homing and co-home-ing mutualisms embedded in the creation of deep civilizations of abundant life where humanity is but an aspect of an entangled web of flourishing creation in God, the ultimate Home of all things. It is in this sense that one can argue that Volf and McAnnally-Linz’s The Home of God, can help us construct meaningful theologies of God the Home of Abundance—as opposed to capitalist, lifeless human-centered homes of scarcity.

For the life of the world, Miroslav Volf and Matthew Croasmun argue, “‘God’s home’ is the ultimate goal of human striving and the ultimate object of human rejoicing.” Miroslav Volf and Matthew Croasmun, For the Life of the World: Theology that Makes a Difference (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2019), 9.↩

Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz, The Home of God: A Brief Story of Everything (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2022), 1.↩

Ibid., 1.↩

Ibid., 14.↩

Ibid., 15.↩

Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, trans. William Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977).↩

Alenka Zupancic, “The Case of the Perforated Sheet,” In SIC 3: Sexuation, edited by Renata Salecl and Slavoj Žižek (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 282–96, 289.↩

Nimi Wariboko, The Pentecostal Hypothesis: Christ Talks, They Decide (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2020), 86.↩

Chammah J. Kaunda, ‘The Nation That Fears God Prospers’ (Philadelphia: Fortress, 2018).↩

James K. A. Smith, “What hath Cambridge to do with Azusa Street? Radical Orthodoxy and Pentecostal Theology in Conversation,” Pneuma 25, no. 1 (2003): 97-114, 109. Italics as found.↩

Harvey Cox, The Future of Faith (New York: Harper One/Harper Collins, 2009), 2–3.↩

This way of thinking is inspired by Rosi Braidotti. See her Posthuman Knowledge (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2019).↩

4.18.24 |

Response

The Home of God in the Body of Christ

The Home of God is stuffed to the brim. Or better, it is overflowing, like its vision of human flourishing. For starters, it is a systematic theology. It is also part of a larger multivolume project. It consists of an extended commentary on not one but three major biblical texts (the Exodus from Egypt, Saint John’s Gospel, and the Revelation of Saint John the Seer). It is an intervention in numerous moral, political, philosophical, biblical, and theological conversations. It is a proposal of what makes for the good life, here and now. It is, in short, just what its subtitle promises: a brief story of everything.

Its ambitious aims are commendable. Theology isn’t good for much when it narrows its gaze from everything—God and all things in God—to something less. As Robert Jenson writes, “theology must be either a universal and founding discipline or a delusion.” Miroslav Volf and Ryan McAnnally-Linz agree. Not for them the false humility of modern theology, which John Milbank once called “a fatal disease.” To be true to itself, theology must function, in Milbank’s words, as a “meta-discourse.” In this book Volf and McAnnally-Linz engage in meta-discourse via meta-narrative, that ineradicably Christian scourge of postmodernity. They are right to do so.

The venture of the book is to narrate cosmic reality through the metaphor of “home.” How? By running the metaphor through three climactic points in the canonical story: YHWH’s deliverance of Israel from slavery in the house of Pharaoh; the advent and exodus of Israel’s Messiah in his death and resurrection; and the same Lord’s descent from heaven at the End of all things to make all things new: “Behold, the home of God is among humans!” (Rev 21:3). The dwelling of God not only with or alongside but in and among his people and, ultimately, all of creation constitutes the theme as well as the aim of each episode and the story as a whole. The world is a homemaking project. God is the homemaker. His epiphany is a homecoming. It is a home for Creator and creature alike, which is to say, it must become a home apt for each and each in relation to the other. Glimpsing this vision of the End, Christians—following Volf and McAnnally-Linz—are able to see where the story was always heading and thereby glimpse anticipations of its finale at key moments along the way.

Here is how they put matters about halfway through the book:

From his coming to his own who did not receive him to his glorification in his death and resurrection, Jesus Christ was God dwelling with humans in the middle of the story of everything to enact a new kind of exodus and make a new kind of home. He revealed himself as the God of the burning bush, the I am. He performed life-enhancing signs. He gave as the new law of the household nothing less than the “law” of his own divine life. He became the Lamb who bore the great sin of apostasy out of his even greater goodness. On behalf of his own, he left the house of slavery by passing through the “sea of reeds” on Golgotha and was raised into new life. In all of this—in his entire life—Jesus manifested his glory as the God who became human to dwell among humans in the tabernacle of his body, as fragile and as particular as any human body. At the end of his journey, the mission completed (John 19:30), he ascended into the divine glory that was his from before the foundation of the world, having brought that very glory into the world to renew creation by making it into God’s home (127).

Later, commenting on Revelation 21–22, the authors observe that “God is in the world and […] the world is in God, more precisely […] the world is in God by God coming to be in the world. […] The mutual indwelling between God and the people that is the goal of Jesus’s mission in John’s Gospel becomes full reality in Revelation—with an expansion. The Gospel has in view mutual indwelling of God and people; Revelation has in view mutual indwelling of God and creation” (212).

In sum, Volf and McAnnally-Linz offer a full-bore Christian theological account of the world, human life in the world, and the inner and ultimate meaning of both, rooted in canonical Holy Scripture and responsive to wide-ranging conversation partners, both modern and ancient, religious and philosophical. It is a wise and attractive achievement. The performance is itself part of the achievement. Here is theology with a capital T, humble but not falsely so, willing to take up questions and answer them, not only defer them; questions with considerable stakes.

My own questions are rather more modest. They concern two matters: the Bible and the church. Let me begin with the Bible.

The exegesis on display is marvelous. Although Volf and McAnnally-Linz take biblical scholars as interlocutors, they are not beholden to them. They show no embarrassment in reading the Bible as theologians, as though (contrary to fact) they were on someone else’s turf. Nor do they subject the reader to death by paper cuts, qualifying each and every interpretive claim with a “perhaps” or “some say” or—God forbid—speculative historical reconstruction. They simply read the text as Christian Scripture, since theology, in their words, “has to be, ultimately, rooted in the biblical witness to God and God’s work” (24–25). Amen and amen.