Consuming Religion

By

4.22.19 |

Symposium Introduction

It’s easy to feel like a fraud in academia. At least it’s easy for me. Some of my nineteen-year-old students read faster than I do. My favorite authors cite theorists that I have read, reread, and still have no idea what they’re talking about. When I was in law school, I got a “C” in my favorite class. I’m ashamed by the number of books I’ve read with the sole purpose of wanting to be seen as a “serious” scholar in my field. As if some philosopher is going to stop and quiz me at a political theory workshop in twenty years to make sure I really belong there. So much wasted time preparing for a hypothetical conversation with a hypothetical European philosopher at a hypothetical academic conference in the year 2039. Why this need to always feel like the smartest person in the room? Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it?

Kathryn Lofton’s path-breaking book Consuming Religion helps me see my academic imposter syndrome in a clearer light. And the help comes from an unlikely source: religion. It was David Foster Wallace who famously told a bunch of Kenyon College graduates in 2005 that “in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism.” His claim was that we all worship something, even intelligence. “Worship your intellect, being seen as smart,” he says, “you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out.” What makes this a form of worship, at least according to Wallace, is not merely devoting your life to feeling intelligent or even being intelligent, but to be seen as intelligent. In a response to a symposium contributor below, Lofton makes a similar point. “We react because of who we are,” she observes, “and what we want to be seen as doing.”

Unlike Wallace, Lofton is not primarily interested in pointing out the things we treat as religions, or even gods. Her goal is to show how the study of religion is essential to helping us understand the many ways we organize our lives. While her case studies involve the Kardashians, Goldman Sachs, cubicles, and desk chairs, Consuming Religion equips us to examine much more. For example, what drives our obsession “to be seen” in a particular way, as a particular person? Not just as a “serious” scholar but as a “fan” of some celebrity? Why do friends encourage me to go to a Radiohead concert so that, in their words, “I can say I went to a Radiohead concert”? How much of today’s bucket list craze is driven less by our sense of adventure and more by our fixation to “say” we traveled somewhere, to be “seen” as someone who visited that landmark? By helping us examine why we attach ourselves to—and are utterly absorbed by—popular culture, Lofton highlights the important connections between our drives for consumption, entertainment, devotion, and the need to “be seen” by others.

Our symposium features essays from scholars in the fields of American studies, history, religion, and law. In the symposium’s first essay, Carrie Tirado Bramen analyzes the ways her experience at a Justin Bieber concert mirrors what likely took place at various nineteenth-century religious revival meetings. Who actually produces the spectacle, Bramen asks. Bieber or his fans? And who consumes it? Does it make sense to speak of Bieber as a consumer of his own spectacle, or merely just the producer? Tim Gloege, in our second essay, highlights the connections not just between celebrity and worship, but celebrity and sacrifice. In addition, he examines what Consuming Religion might mean for thinking about hierarchy, control, and domination in various contexts—including our institutions of higher learning.

Essays by Rhon Manigault-Bryant and Winnifred Sullivan round out our symposium. Manigault-Bryant considers Lofton’s book in light of the “long, horrid history of black women’s bodies being forcibly and perilously consumed.” By raising questions that implicate us all in the violence of consumption, she forces us to not just recognize our participation in it, but to own that violence as well. “What exactly is getting consumed when we see black women’s bodies on the screen?” Manigault-Bryant asks. “What precisely has our sacred desire to consume done when we consider blackness?” In our final essay, Winnifred Sullivan reads Consuming Religion alongside the 2018 Supreme Court decision, Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, a case involving a baker who refused, on religious grounds, to design a cake for a gay couple’s wedding celebration. Drawing on a rich array of voices like radical feminists, critics of the Wedding Industrial Complex, and even the late great Anthony Bourdain, Sullivan praises Lofton for inviting us to ask the questions that really matter. “Can we find an uncommodified religion,” Sullivan asks, “imagining new ways to share and care?” I sure hope so.

When I assigned Consuming Religion in my senior seminar about faith, vocation, and calling, students were enthralled. Whenever I could tell my lectures were getting boring, when my students started texting, resting their heads down on the table, reaching for a bag of Doritos or a stick of gum, I had one go-to weapon. “You might remember what Kathryn Lofton had to say about this,” I would remark. Before I knew it, heads were up, eyes were open, phones were tossed. Doritos stayed in place. “What she says makes a lot of sense,” a student would consistently point out. “Damn,” said another, “Damn, damn, damn.”

I said the exact same thing when I first read Consuming Religion. It’s the kind of book teachers text their colleagues about as they finish each chapter, sending screenshots of highlighted excerpts throughout the day. It’s the kind of book students talk about after class, in the cafeteria, in their dorms, sometimes until 2:00 in the morning. Some of my favorite comments from students included: “I need to give this book to my little brother”; “Where do I learn to write like her?”; “God, I can’t stand Goldman Sachs” (though, to be fair, the student drew this conclusion not from Lofton’s ethnographic research of the bank, but from a human rights class she took a year earlier); and, last, the predictable, “I wonder what she thinks about Fortnite!” Yes, what does Lofton think about Fortnite? We may never know. But the fact that students now saw Fortnite as something that could not only be played or consumed but thought about—and thought about with tools from the field of religious studies—meant that Lofton had done her job. “Tell us more,” students would always say when she came up in conversation. So, in a very minor token of appreciation for them—and as an apology for failing to do justice to her brilliant insights during the seminar—I helped curate this symposium so Lofton could do just that: tell us more.

4.29.19 |

Response

Consuming Religion and Corporate Belonging

“Consumer culture” is a complex system. It consists in techniques of mass production and mass marketing and mass media, of commodified grains and standardized bolt diameters. It is inscribed in trademarks, contracts, and consumer protections, in certificates of stock and double-entry ledgers. It is powered by generators, transmitted over communication wires stretched thin, and stored in servers buzzing like hives. It is embodied in people who conjure identities from grease and steel, zeros and ones, and by choosing (always choosing). All this is “consumer culture.” It is a system that organizes us and our resources, a tangled set of solutions to contingent problems. None of it was inevitable. There was a time when it was not, and there will be a time when it will not be again.

I think about consumer culture this way because I am a particular type of historian. I was socialized by a university history department and taught its methods: archival research measured in linear feet, deep contextualization of my subjects, and analysis conducted through the narrative form. It shapes the way I approach religious subjects. I seek people and institutions and things. I tell their stories and connect them to other stories about resources, power, relationships, and meaning-making.

This background also shapes my approach to Kathryn Lofton’s remarkable book, Consuming Religion. Although I was not trained in many of the analytical methods it deploys, I am an avid consumer. It helps me see things that were once invisible and ask questions that were otherwise impossible. It makes me reflect on my methods, and keeps me cognizant of the assumptions framing my work.

My contribution is not to place this study in a particular theoretical tradition, nor to evaluate its discursive constructs. Rather I want to take it out in the field as an archival historian. Lofton has crafted an exquisite set of theoretical tools; let’s see what they can do.

***

Theorists of religion have taught me to see religion like any other phenomenon of human culture. Yet curiously, our field often treats the problem of defining religion as exceptional. It results, Lofton wryly notes, “in undergraduate program descriptions and doctoral mission statements that look more like the result of a game of Exquisite Corpse than reasoned roundtable deduction” (3). Yet, definitions are simply ways of freezing in time a complex, ever-evolving, multidimensional set of relations, practices, and ideas. Definitions have limitations and introduce distortions, but these can be overcome by holding to them loosely.

Lofton’s first accomplishment is to offer a more pragmatic approach to the problem of defining religion. Whether we like it or not, affirm it or not, religion “exists”—as a category, a domain, and a divider of things. It exists because millions of ordinary people declared it so and use it as such. And so, it is conjured like the other impossible things we study: race, gender, class, nation, ethnicity, market, and commodity. As humanists, we should be interested in understanding its operations.

Religion has no singular meaning; rather it inhabits a particular field of operation. It relates to our values and the way we understand the world. It organizes. It offers promises of freedom. But above all, it is social. Religious frames are not chosen by us any more than we choose our native tongue. We are socialized into them and they shape our thinking.

This framing runs counter to prevailing assumptions (especially after Charles Taylor) that modern religion is private, individualistic, and chosen. “No matter what you think you are relative to some abstract notion of religion,” Lofton argues, “you are . . . being determined by it” (xi). In fact, these assumptions are evidence of modern religion at work—specifically, a religious frame called neoliberalism, which organizes both our consumption and our vision of “the self in the world as a calculatingly sovereign person” (9). And so, it seems that “the term religion may still have some critical life” as a way of thinking about things social and “certain outlines for human framing” (2).

With the boundaries of inquiry set, Lofton models various techniques for comparing sets of objects and practices that are often poised as binary opposites (either “religion” or “consumption”), but which share deep commonalities. These inquiries feel provisional, even improvisational, in the best sense of the word. What happens when we treat consumption as our preeminent ritual? What are the connections between the operations of modern celebrity and sacrifice? What if we consider cubical space as religious space? “Religion isn’t something that can be solved with one lens, or state in a single sentence,” Lofton notes. “To get at its move of containment, you need to grab for many containers; to get at its claims of freedom, you need to identify many thruways” (261).

***

We can see the power of Lofton’s technique in her bold equation of corporation and sect. In modernity, they “are not mere analogies; they are synonyms. To join a corporation is to join a sect; to join a sect is to join a corporation” (203). Initially, this seems implausible. Is not a corporation a business? And is not profit its singular end? (According to economist Milton Friedman, the high priest of neoliberalism, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”) Are not sects nonprofit entities that, by definition, pursue something other than profit?

But as we drill down, the binary opposition between corporation and sect does not hold. Legally speaking, a “nonprofit” is a “nonprofit corporation.” And what is a corporation, but a “group of people authorized to act as a single entity and recognized as such in law” (203)? All corporations go through the same process of creation; all are treated as legal persons; all can own property and enter into contracts. All, in other words, are variations of the same basic type.

Must the purpose of business always be profit? In 2017, Forbes contributor Jon Markaman used Amazon’s two decades of regular operating losses to suggest that “profits are so yesterday.” This is hyperbole, but there’s no denying that Amazon’s earnings continued to be miserly despite its immense market power. Why the unrelenting quest for expansion at the expense of earnings? A long game to greater profitability, in part, but also a desire for the power to shape social reality. That Jeff Bezos believes a for-profit corporation is the best way to get there does not make the goal any less sectarian.

From the nonprofit perspective, differences between sect and corporation are equally elusive. The sacred 501(c)(3) designation offers freedom from certain tax burdens, regulatory controls, and investor demands. But it also comes with restrictions on things like political speech. Call them revenues or donations, but corporations need funds to keep the lights on. Are investor demands for profit a greater incumbrance than donors’ dictates? Does a nonprofit status impede the self-enrichment of participants? (Ask the executives of Blue Cross / Blue Shield or the megachurch minister with a lucrative book contract.)

Perhaps, then, the primary goal of any corporation, whether Walmart or the Presbyterian Church USA, is simply to survive and then to do something—anything—else. Once you start down this path, it becomes difficult to remember why you ever thought they were different.

Consuming Religion thus helps me un-see the patterns that have imprisoned my imagination. But erasing old boundaries between sect and corporation is only half the revolution. We must now ask whether there are any differences between corporations and whether those distinctions matter.

***

If a corporation is simply a “group of people authorized to act as a single entity,” who exactly are the people we talking about? Legally, we know it consists of the signatories to the articles of incorporation and those listed on the official membership role. They elect a board of directors—the body that appoints and oversees the executives who make the day-to-day decisions. But what is required to get on that membership list?

In for-profit corporations, members are those who own voting stock. And because the amount of stock determines the number of votes, those holding a controlling interest wield immense power—at times, even autocratic control. Corporations with many stockholders might operate more democratically, but corporate control is always for sale.

Nonprofit membership comes in two varieties. The traditional model offers formal membership on a broad basis. Nearly everyone involved in most Protestant denominations or a local housing co-op are legal members of a corporation and participate in corporate decisions. The second variety mimics the for-profit form. These corporations limit legal membership to those who sit on the board, thus bypassing the messiness and inefficiency of democratic governance.

The key division, then, is not between corporation and sect, but between hierarchical and distributed governance. Profit or not, explicitly “religious” or not, this is the division that matters. Because membership matters.

Relations within corporate structures are intrinsically cooperative. If the whole succeeds, members also succeed; if members can’t figure out how to get along, the corporation collapses. But a corporation’s relationships to outsiders are intrinsically antagonistic. And to be clear, employees and customers are outsiders, not members. Nor are participants in nonprofits who do not have voting rights. “Members” of a public radio station or the National Geographic Society are essentially subscribers—consumers of the products the corporation produces. Whatever the rhetoric about cooperative, win-win relationships between corporations and their employees or consumers, such arrangements are transitory and unstable.

Therefore, it is essential to understand the contradictory ends of consumers and the corporations that service them. By my reading, consumers want the freedom to create unique identities by their patterns of choosing. Corporations, in contrast, seek efficiency and predictability. Their end is monopoly: not to meet consumers’ wants, but to control their needs. Capitalism is discontent by design, a system of all but asphyxiated consumer satisfaction. Consumers want meaning through choices; corporations want the old soviet breadline.

We must also differentiate between the wants of employees and their corporations. Employees want safe and meaningful work on their own time, in their own environs, and by their own rules. They want the full fruit of their labor. (Or, perhaps what they really want is no work at all.) Corporate employers want commoditized labor: physical strength and intellect of their workers without their bothersome wills. They make accommodations when necessary—if employees have market power because of unique skills, if governments threaten regulations, if unions threaten strikes, or if mobs threaten revolt. These accommodations can look a lot like belonging. But if labor history has taught us anything, it is that those concessions evaporate when the threat is contained.

Consumer culture, which seems so solid, is actually a braid of opposing interests and mutually exclusive logics and goals. These differences matter. The coercive power of a group over an individual member is real, but different from the power of the corporation over the people it wishes to commodify. If I can borrow from Lofton’s boldness and take my own normative turn, it’s worth asking if one of these corporate forms is better than the other.

***

Consuming Religion offers many other productive avenues to explore. Most tantalizing is that other class of nonprofit corporation lurking in the shadows of Lofton’s book: the university. Academia is ripe for religious analysis. How do the corporations to which academics belong organize us and our scholarly work? Are disciplinary disagreements over proper terminology and methods really sectarian disputes in disguise? Are we the new holy warriors? What might the tools of religious studies tell us about this tangle of institutions and power, rules and resources that is our socializing context?

I am an archival historian. I tell stories. I have been shaped by certain institutions and professional norms. Am I making a sectarian declaration in these statements? I am a scholar without an institutional home. Am I a member of academia or am I merely being commodified by it?

Consuming Religion offers no new coherent frame to replace the old, no final definition of religion that ends discussion. It offers something much better. It reveals new worlds to explore and offers new tools to do that work. It is a new beginning. I can’t imagine that we will ever write our histories of religion (or consumer culture) the same.

5.6.19 |

Response

Consuming to Love, Consuming to Hate, Consuming Religion

I hate the very idea of Consuming Religion, and I hate Kathryn Lofton for writing it.1 There, I have said it, and a veritable gauntlet is now thrown.

And yet this hateful declaration is a misnomer. Kathryn Lofton is not in any way, shape, or form someone to be despised. In fact, she is a delightful human being with an incomparable sense of humor and impeccable musical tastes. And, her book is far from a despicable, empty foray into the spaces where that which is consumed is religion and that which is religion is consumed. Rather, it is an excoriatingly precise, deep dive into how religion completely informs what we believe, what we desire, what we binge, what we buy, what we encounter and what we consume, just as what we consume completely informs what we encounter, what we buy, what we binge, what we desire, and what we believe. I hate Kathryn Lofton and by extension what she has crafted (or, more aptly, conjured) in Consuming Religion because she is so damn right, and her rightness disturbs me.

As is appropriate for religion, I should contextualize my hateful declaration with a confession. Kathryn Lofton and I have some key things in common. Lofton’s consumption portfolio is striking for its intersections with my own. We both inhabit elite academic institutions, and these spaces yield their own particular kinds of students. Yale University, where Lofton teaches, has Goldman Sachs. Williams College, where I teach, has a famed “art mafia” (among other affiliations). As faculty, we both struggle with the complicity of corporatized consumption signified in the branding of the university, and grapple with the “incongruity between pop profile and individual reality” (249). Corporate liquidity achieved. Goldman Sachs and art, like god, endure.

And there is more. I am, like Kathryn Lofton, a religionist. I happen to write and think and teach at the intersection of religious studies, Africana studies, and gender studies, which has taken me on an unexpected journey into the popular. In much of my most recent writing, I have tried to unearth the inherent religiosity of fat drag performance as made popular in films by black male comedians.2 The commodification of religion is also my question, though contemporary film is my surprising spiritual muse.

Like Lofton, I spend considerable time moving beyond the savage intellectual mockery that arises when our colleagues not-so-subtly inquire, “What does this have to do with the study of religion again?” Or, as Lofton so perfectly posits, “These conversations are both serious and unserious. They are serious because I do treat the archive of culture as a repository of religious substance; they are unserious because the fact that I do this has become an easy source of satire” (247). I too boldly swagger toward—only to sheepishly retreat from—the ongoing and arguably tumultuous relationship between religion and commodification, and the satire that accompanies it. As “out there” as this relationship seems, Lofton is in no small company of thinkers. She embraces her community of saints—Emile Durkheim, Peter Berger, Gordon Lynch, Gary Laderman, and Colleen McDannell, among others—with rigor and verve. They have all tried (in numerous and at times disparate fields no less) to make sense of what we mean by “religion,” “popular,” and “culture” and the simultaneously infinite, indecipherable, and clandestine spaces where religion and popular culture meet.3 For me, Lofton’s articulation of religion helps us consider Stuart Hall’s evocative question anew: what exactly is this “religious” in religious popular culture?4

So when I began reading Consuming Religion, I was ready to engage with one of “my people,” who Kathryn Lofton undoubtedly is, because she takes this huge, hard-to-describe thing we call “religion and popular culture” seriously, and she tussles with it at every angle, from all directions, and in all the best academic ways without sacrificing thoughtfulness and accessibility. She is honest about her own fumbling relationship to religion and popular culture and her efforts to maintain the façade of “proper sociological distance” (18). This is the Lofton I especially love to hate. She confronts, with great integrity, the utter idiosyncrasies that belie our understandings of the social and of socialization, upends our deep need for binge-watching Netflix and those dreadful Kardashians; and provokes us with the “malignant ontological consequences” (35) that we have inherited from the office cubicle. (And, in an apt yet ironic turn of events, I have written this engagement with Lofton all the while seated in my beloved Herman Miller chair—an object that I had no idea came with all of its religious ideation and missiological baggage!)

My engagement with Lofton’s work unfolds (perhaps maddeningly) much like my encounter with the text. For the first time in a long time, Consuming Religion is a book that I could not help but read out of sequence. Rather, I followed the ephemeral spirit of consumption that Lofton so poignantly and adeptly lays bare. Take, for example, the following phrase:

I want to illuminate this ubiquitous thing [the creation and mass production of the office cubicle] as an arena for scholarly work in the study of religion, insofar as the very naming of its un-specialness (its neutrality, simplicity, ubiquity) included arguments on behalf of communities, their best practices, and their best minds. (39)

If you had any doubts about the supposed line demarcating the sacred and the secular, read chapters 2 and 4 on the sacred formations of cubicles and soap closely, for they reveal that distinction as a bald-faced lie.

That I savored this book in the way I typically do a novel speaks as much to the appeal of the product as it does Lofton’s writing style. Making the evasive perceptible is Lofton’s goal, and she succeeds as she prompts us to recognize that corporation is in fact another word for sect, reminds us that purity balls are prime examples of appropriate ritual behavior in our modern contexts (which in chapter 3 Lofton craftily names scientia ritus), and terrifies us (well me) for the ways that parenthood is unequivocally a religion or less stringently, a mode of religious expression. Whether we parentfolk like it or not, we are the church of parenthood’s religious agents (and I will say nothing else about this, lest I ruin that especially delightful chapter 7).

Fictional Doubles, Consumption, and the Black Female Body

My love-hate relationship with this book stems from the ways it has provoked my thoughts about my recent scholarship. I consider (mostly while fuming in that same Herman Miller chair) the paradox that lies at the soul of Consuming Religion: regardless of whether we agree (and whether we like it or not), the boundaries between religion, the popular, and culture are so fluid they are indiscriminate, and as such, seep into the everydayness of our interests, our livelihoods, and our very beings. To be religious is to consume, and to consume is to be religious. This is a particularly damning incongruity because Lofton’s claim suggests that no matter how hard we try to isolate and decipher, to extract or to discern, the Spirit of Consumption wins. Every. Single. Time.

This vexing fact is utterly inescapable, and I suppose we would all be better of starting from there and moving on with our lives. And yet, I cannot, for it is the pervasiveness of religious consumption that haunts me, and by extension, my work. I wrestle with understanding the commodification of the black female body. I believe, yes believe, that popular filmic distributions of black women’s bodies are another precarious form of consumption. And, when that already unpredictable visual representation is hyperbolized, parodied, and oversimplified through the performance of fat drag (e.g., black male comedians dressed as women in fat suits), that which is teetering on a jagged edge of cultural commodification becomes an object that we tacitly, yet dangerously consume. That consumption, which I have long known and Lofton affirms, is absolutely spiritualized, and we viewers are granted permission from on high to consume black women’s bodies, and to do so unflinchingly, unapologetically, and uncritically.5

Put another way, there is a long, horrid history of black women’s bodies being forcibly and perilously consumed. Black women continue to contend with these legacies and with what Debra Walker calls “fictional doubles,” where the images of black women that have been externally imagined, created, manufactured, defined, and consumed by others (especially via cultural myths, television, and, as I argue, film) collide with and silence who black women see and know themselves to be.6 It is challenging enough to consider what it means if one is never actually in control of an image, and that the value we ascribe to anything is entangled with how we consume it. Couple this idea with how “being consumed” presupposes being-ness, and black women’s bodies have historically been (in a ontological sense) considered in-human(e), then what exactly is getting consumed when we see black women’s bodies on the screen? What precisely has our sacred desire to consume done when we consider blackness?

It is this all-consuming spiritual labyrinth that is my muse, and that undergirds why I love to hate Lofton. She has, in effect, increased my lexicon for how to consider consumption. Consumption is not, as bell hooks suggests, merely “eating the other.”7 Rather it is as agentive as it is involuntary, and as much about what we choose to believe as it is what we must believe in order to consume. This is a troubling betwixt and between, a haunting that is already and not yet. Lofton intervenes in the “innocent bystander” model of consumption, and in so doing, holds us liable for being anything other than uncritical. She reminds us, “Religion isn’t only something you volunteer to join, open-hearted and confessing. It is not only something you inherit, enjoined by your parents. Religion is also the thing into which you become ensnared despite yourself. Religion is one way to describe how we organize ourselves in the salesperson’s world” (ix).

Kathryn Lofton has deftly articulated the religious essence of consumption, and its subsequent sociality into which we have been initiated, or, as Lofton aptly puts it, captured. And her unearthing of relationships of value is precisely what has captured me. When I consider the meanings of value and consumption in relation to the black female body, I am forced to be even more mindful of the implications of consuming uncritically. In the end, then, I love that in Consuming Religion I have found a work that is so perfectly disturbing.

Reading Consuming Religion left me feeling as if I had been snatched out of my tiny bucolic town (which we locals call “The Shire”), suddenly thrust into the heart of Midtown Manhattan, and just when I thought I had figured out what to make of that ad in Times Square, unexpectedly teleported back into my comfy Herman Miller chair (crisis averted!). Kathryn Lofton has successfully revealed just how pervasive religion is in what we see, believe, and what we consume.

Lofton, Consuming Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).↩

LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant, “Fat Spirit: Obesity, Religion, and Sapphmammibel in Contemporary Black Film,” Fat Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Body Weight and Society 2.1 (2013) 56–69. See also Manigault-Bryant et al., eds., Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Productions (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).↩

Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (London: George Allen & Unwin 1964); Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (New York: Doubleday, 1967); Gordon Lynch, Understanding Theology and Popular Culture (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005); Gary Laderman, Sacred Matters: Celebrity Worship, Sexual Ecstasies, the Living Dead and Other Signs of Religious Life in the United States (New York: New Press, 2009); and Colleen McDannell, Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). See also R. Laurence Moore, Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).↩

Stuart Hall, “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?,” in Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (New York: Routledge), 465–75.↩

This is also taken up in Lofton’s book Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).↩

Debra Walker King, ed., Body Politics and the Fictional Double (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), vii–viii.↩

bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End, 1992).↩

5.13.19 |

Response

No Cake; No Reservations

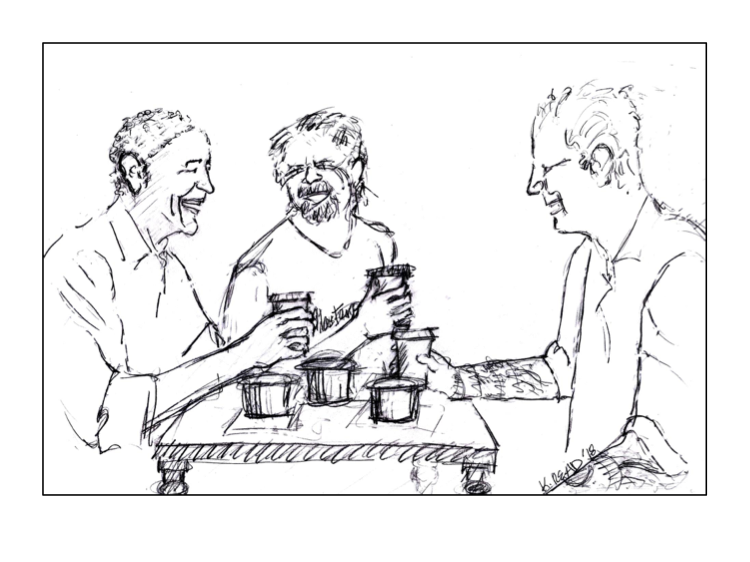

“Barack Obama, Jack Phillips, and Anthony Bourdain”; drawing by Kay Read, author of “To Eat and Be Eaten: Mesoamerican Human Sacrifice and Ecological Webs,” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Material Religion, edited by Vasudha Narayanan (UK: Wiley-Blackwell, in press)

Kathryn Lofton’s new book, Consuming Religion, invites us to consider the distressing and obsessive auto-cannibalism that is contemporary consumer culture in the United States. With restless and characteristic brilliance and erudition, she takes us on a chilling tour of the immense archive of the American marketplace—figured as religious; she combines a serious engagement with the great thinkers on religion with astonishingly complex readings of a varied range of US cultural phenomena: the office cubicle, cleanliness, parenting, the Kardashians, Goldman Sachs, Herman Miller, 9/11, the internet.

Lofton’s title could be read in various ways. But one way to read it is to see it as an indictment of our apparently concerted and active destruction of our very means of survival, the social nature of all kinds of consumption seen to have gone horribly wrong. And we do not seem to be able to help ourselves. Yet, having revealed the sacrificial violence at the heart of our common life today, Lofton also insists in various ways and at various points in the book that “religion may still have some critical life.” She urges us to commit ourselves to making religion “do something different”—to “freedom from the primal horde.” Again and again, she exhorts us, her readers, to do otherwise: “Conceiving of alternative structures of collectivity requires not that we eradicate human desire but that we imagine new ways to share and care for those who have not.” She urges us to share and care.

I am not sure we can do that. I am not sure she believes it is possible. That is, in part, the message of this book, combining the relentless logic of French sociology with the puritanical rage of the American Jeremiad.

I study what law makes of religion. Law and religion are each fields, taken separately and together, in which Americans have tried to make things better. But law’s religion today seems broken. Law seems broken, and religion too. Exposing the interested ignorance of the courts when it comes to religion is child’s play. Any competent scholar of religion can do it. Lofton, too, laments the legal state of things when it comes to religion, particularly corporate religion.

Take the most recent religion decision of the US Supreme Court, Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, decided in June 2018. The case originated in Lakewood, Colorado, outside Denver, when Charlie Craig and David Mullins approached Jack Phillips, the baker-owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop, asking him to design a cake for their wedding celebration. Phillips responded that he could not do that because he was religiously opposed to same-sex marriage.

Craig and Mullins filed a complaint with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, arguing that Phillips had violated the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act. The commission ruled in their favor, as did the Colorado Court of Appeals. Phillips then successfully sought a hearing in the US Supreme Court. The majority on the court, in its turn, in an opinion authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy, reversed the earlier courts’ decisions, finding the Colorado Commission to have been biased against Phillips, as revealed in statements made by commissioners in the course of the hearing. One such statement was this:

I would also like to reiterate what we said in the hearing or the last meeting. Freedom of religion and religion has been used to justify all kinds of discrimination throughout history, whether it be slavery, whether it be the holocaust, whether it be—I mean, we—we can list hundreds of situations where freedom of religion has been used to justify discrimination. And to me it is one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric that people can use to—to use their religion to hurt others.

Because the court found the Colorado Commission’s process to have been hostile to Phillips, the court did not reach the constitutional questions raised in the case as to whether Phillips had either a first amendment free speech or free exercise right that trumped the Colorado anti-discrimination statute.

The ruling in Phillips’s favor was almost instantly drawn into the maw of social media and consumed, à la Lofton, reduced to a meme. This was a common image from those who support same-sex marriage:

There are interesting legal questions raised in the dissent by Justice Ginsburg about the evidence adduced by the majority to prove hostility on the part of the commissioners, suggesting that the majority’s effort to avoid the constitutional question was somewhat disingenuous. Indeed, one might see its refusal to confront the possibility of a constitutional violation at the heart of the encounter as profoundly cowardly, parallel to the cowardice revealed in Robert Cover’s reading of the court’s 1982 Bob Jones University decision. Cover saw the court in that decision as deflecting the racial discrimination question at issue by deciding the case on statutory rather than constitutional grounds.

At a moment when the court is arguably in a profound crisis of legitimacy, calling the court to account is surely right today as it was in 1982. Can we remake this decision to make religion do something different, as Cover tried to do? Can we find an uncommodified religion, imagining, in Lofton’s words, “new ways to share and care?”

As I discussed in a blog post on the Masterpiece Cakeshop decision at the Immanent Frame, religion for both the court and for social media seems to have been reduced today to devout beliefs about sex and reproduction. No actual evidence that these beliefs are religious is needed for this reduction. Opposition to abortion. Opposition to same-sex marriage. Everyone knows that these are nonnegotiable religious positions. While everyone also knows that favoring them is not. Favoring free access to abortion and same-sex marriage is liberal and secular. Accommodating the free exercise of religion has often come to be seen as nothing more than a demand for accommodation of these oppositional “religious” views. This view of the matter can just be asserted. No evidence is apparently needed. Never mind the uncomfortable and inconvenient fact that there are religious-minded and secular-minded folks who take both sides on both issues.

Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Masterpiece Cakeshop reflects these current prejudices, including the often noted tendency of the court to treat religion as a matter of sincerely held belief. In describing Phillips, he tells us that

Phillips is a devout Christian. He has explained that his “main goal in life is to be obedient to” Jesus Christ and Christ’s “teachings in all aspects of his life.” And he seeks to “honor God through his work at Masterpiece Cakeshop.” One of Phillips’ religious beliefs is that “God’s intention for marriage from the beginning of history is that it is and should be the union of one man and one woman.” To Phillips, creating a wedding cake for a same-sex wedding would be equivalent to participating in a celebration that is contrary to his own most deeply held beliefs.

These few sentences anchor the constitutional claim, summing up what it is to be religious today in the United States.

Accommodation of beliefs in opposition to same-sex marriage could get out of hand, however, Kennedy concedes, so several pages later he suggests that it should be limited to clergy. He assumes that everyone would recognize and approve this limitation:

When it comes to weddings, it can be assumed that a member of the clergy who objects to gay marriage on moral and religious grounds could not be compelled to perform the ceremony without denial of his or her right to the free exercise of religion. This refusal would be well understood in our constitutional order as an exercise of religion, an exercise that gay persons could recognize and accept without serious diminishment to their own dignity and worth.

Extending what he took to be a well-understood clerical privilege to others involved in providing services for weddings might, however, create a social stigma parallel to Jim Crow, as he explained:

If that exception were not confined, then a long list of persons who provide goods and services for marriages and weddings might refuse to do so for gay persons, thus resulting in a community-wide stigma inconsistent with the history and dynamics of civil rights laws that ensure equal access to goods, services, and public accommodations.

Well yes. Exactly. Unfortunately religion can’t be divided up that way, especially with respect to weddings. Everyone is involved. The web of consumption Lofton describes with Durkheimian intensity makes up the wedding industrial complex. Read the wedding columns in the newspaper. Clergy are increasingly rare and today living under a cloud of accusations. Instead, there are mail-order ministers, friends, family, and wedding planners. Religion in the United States doesn’t work in that hierarchically imagined way about anything. Kennedy is misinformed. Clergy are rarely consulted or present any more. In traditional Catholic theology, they are unnecessary for the sacrament of marriage.

But religion is always about a community. What community does Phillips belong to? In the opinions in this case, Phillips’s religious objection to baking for sinners appears entirely individual, unconnected to any theological tradition or any religious community in a traditional sense. Indeed, it arguably could not be so linked. His sincere religious objection to baking for sinners might be seen rather as a product of the very consumptive culture Lofton describes, his response to Craig and Mullins wholly patterned by the increasingly divisive and sneering partisan politics of the last several decades.

Is there a way out of this bind? What about the cake itself?

Taking our cue from Lofton, and her theory that our lives as consumers have become even more devoutly religious under late capitalism, we might consider the religious consumption evident in this case as all centered on the cake. All of the characters, Phillips, Craig, and Mullins, were consuming their corporatized religious sacrament through the making and buying of the now de rigueur custom wedding cake. Another cake from the social media response:

With Lofton, I wonder whether it could be otherwise? Whether it is possible to do religion differently? Not as consumption but, as Lofton barely whispers in the last few lines of her acknowledgments, “as something that refused sentiment . . . something that presumed no public recognition or private predictability . . . something that remained within the precarious challenge of encounter.”

Can we together reread religious history as one with the resources for us to reimagine rather than destroy our collective life? With Nancy Levene, in her recent book, we might take up the challenge of what she calls “reforming the collective.” Levene insists that “all human life takes place in collectivities. The question is how to value them.” By “value” I take her to mean at once the need for evaluation and the need for cherishing.

The Masterpiece Cakeshop decision was announced on Monday, June 4, 2018. On Friday, June 8, Anthony Bourdain was found dead in his hotel room in Strasbourg. On June 9, 2018, Courtney Bender drew attention to the link between these two events in a tweet responding to my June 8 blog post on the Masterpiece Cakeshop decision. She wrote: “Spent my day playing out various versions of what might have transpired if Anthony Bourdain had taken No Reservations to Masterpiece Cakeshop.” Immediately what came to my mind was Bourdain seated in the shop with the baker and his customers—on little plastic chairs. A transposition, in other words, of the well-known video of Bourdain and Barack Obama eating at a noodle shop in Saigon, filmed for an episode of Parts Unknown.

As they eat and drink their beer, Obama and Bourdain speak of their common conviction that, in Obama’s words, “people everywhere are pretty much the same.” Around them Saigonese are eating their noodles. A couple. A family. A man alone. Presumably the secret service detail. All on plastic chairs. If we imagine Bourdain as the minister of this church—they are all convened to speak of peace—and, importantly, to eat together in public.

I don’t want to speak for her but I will take it that Courtney was suggesting that rather than regarding the cake decision as revealing the truth about religion and about our unbridgeable predicament, that is, that we are implacably divided between those who do and those who do not favor same sex marriage, we might rather imagine another truth, one argued for by Bourdain in his travel and food program No Reservations. Instead of the tight jurisdictional focus on the opposition between Phillips and Craig and Mullins, trapped as they are into consuming their religion, we might consider a broader community that encompassed all three.

No cake. Just noodles. And beer. Or, as imagined in Kay Read’s drawing at the beginning of this piece, coffee and muffins. No reservations.

We need, as Ben Berger has argued, to change our legal aesthetics. In this other world he imagines, we could speak of the hospitality and table fellowship that all religions teach. We could see a cake shop as religion, a place, in Lofton’s words, “within the precarious challenge of encounter.” In this scenario, Phillips’s evident gift for baking would be in service of this other community. But no wedding cakes.

What if, inspired by the work of radical empathy taught by Hillel Gray at Miami University of Ohio, we listened to Phillips instead of hating on him?

by Rose Harding, a Bloomington artist

Bourdain and Obama are, of course, a part of the very celebrity world of consumption Lofton describes. Community is a fragile matter. Responding to a British politician suggesting that he had no need to visit Ireland to make a plan for the border post-Brexit, actor Stephen Rea in a moving video posted on the Financial Times website, remembering the aftermath of the Good Friday Peace Accords, says, “We’re holding our breath again because we know that chance and hope come in forms like steam and smoke.”

I offer this essay as what James Boyd White calls an “act of hope,” a modest effort to make religion-in-law do something different. And, taking cues from a feminist scholar of religion and a feminist critic of Robert Cover’s work, envisioning a religion not built on narratives of sacrifice.

There is work to be done.

Carrie Tirado Bramen

Response

The Varieties of Religious Experience from Justin Bieber to Beyoncé

Whether it is Oprah or the Kardashians, the signature move of Kathryn Lofton’s work is to unsettle the boundaries between religion and secularism, between the sacred and the profane. Her mise-en-scène is popular culture in all of its range and complexity; and her theoretical guide is Durkheim, who understood religion as a fundamental part of our socialization, best summarized in his dictum: “The idea of society is the soul of religion.” For Durkheim, religion creates identities, solidarities, and meaning for human societies. It is the glue that holds communities together; it is the means by which individuals define their purpose. What interested Durkheim about religion is the same thing that Lofton finds so generative in Consuming Religion, namely the centrality of sociality in discussions about religious practice. To quote Lofton on Durkheim: “Socialization is our humanization, and religion is the primary social form by which our socialization takes place” (18).

In the twenty-first century, our socialization primarily takes the form of consumerism mediated in large part through technology, but this seemingly secular practice does not mean that religion has now been placed on the back burner. Our consumerist habits—defined by the rituals of shopping and celebrity worship—have incorporated the fundamental elements of Protestantism into everyday compulsions and obsessions.

Although Lofton’s breezy and conversational style immediately draws the reader into her narrative, she doesn’t allow us to become too comfortable. By the end of her introduction, she breaks down the fourth wall and addresses her readers directly through the second-person “you.” Reminiscent of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s writerly tactic of addressing her readers directly (echoing in part the Calvinist minister in the pulpit), Lofton writes: “Whatever your spirit, whatever your ritual, you are in it. You are being consumed by the social inevitability of consumer decision.” Lofton calls out any scholarly reader who maintains a condescending attitude toward the subject matter. We are all implicated in the rituals and beliefs of a consumerist culture: “you are in it.” There is no escape. But unlike the Calvinist minister with thoughts of declension uppermost in his mind, Lofton offers the reader a way out: consumer culture can be the opiate of the people, a symptom of our “alienated self-consciousness.” Or, it can be a way to articulate alternative forms of consciousness, which can in turn free us from “the very obsessions it compels” (13).

I take this refrain—“you are in it”—as an invitation to reflect on how I have been implicated in the very consumerist marketplace that we may at times look at with disdain and embarrassment. I recalled how in July 2016, I took my then eleven-year-old daughter to see Justin Bieber in his Purpose World Tour at the indoor arena in downtown Buffalo. The concert experience, combined with what Bieber did after he cancelled his world tour, touches on several key points in Lofton’s Consuming Religion, which are worth discussing at length. How is fandom an expression of religiosity (in this case, of the aptly named “Beliebers”)? And what precisely are the power dynamics of consumerism in the collective mania of a teen pop concert?

Our seats were fairly close, and Bieber’s grandparents who had traveled from Ontario, Canada, were rumored to be nearby. We sat at one side of the stage, so we could see Bieber go from backstage to onstage in a matter of minutes. Two things stand out the most from that evening. First, the contrast between Bieber, hanging out backstage with his dancers casually doing warm-up exercises, and then after the lights dimmed and the smoke machines started working, he transformed into a pop icon before thousands of shrieking girls (and a few moms).

Second, as soon as he appeared at the side of the stage, even before he was visible to the entire arena, the screaming started and it grew more audible and increased with intensity with every step he took. The atmosphere became frenzied by the time he was elevated inside a glass box, as if he were the desired object displayed inside a department store window.

It was the twenty-first-century equivalent of a nineteenth-century revival meeting with everyone standing, while the majority were screaming, jumping, waving their arms, singing, clapping, and for some, even weeping tears of joy. The fact that this took place in Western New York, the burnt-over district of the Second Great Awakening, made the religious undertones even more salient. But the one ubiquitous gesture, which illustrates Lofton’s point about the fusion of celebrity and technology into what she calls “mechanized intimacy,” was taking photos constantly with smartphones. All one could see at points were the flashes going off. When Bieber stopped to converse with audience members between songs, the kids would immediately start taking photos and posting them on Snapchat and Instagram. This obviously annoyed him and was reminiscent of a remark he made during an interview, that he “feels like a zoo animal.”

In contrast to the 19,000 screaming fans, Bieber appeared to be going through the motions, oscillating between boredom and annoyance. He seemed to be counting down each song before he could return to his trailer and head to the next gig. He was on automatic pilot and occasionally he slipped into flagrant lip-synching, which I couldn’t help but like, as a contemptuous gesture on his part in refusing to please his audience. To watch him perform was a reminder that you were watching someone having to work. Unlike the tireless work ethic of the Kardashians, Bieber hasn’t internalized the American obsession with work or what James Surowiecki in the New Yorker has called the “cult of overwork.” Though he was obscenely well-remunerated for the performances, he personified alienated labor. A year later, after sixteen months of touring to over forty countries, he cancelled the remaining fourteen scheduled dates. I was surprised that he stuck it out that long.

After reading Lofton’s book, I reflected on Justin Bieber’s performance and wondered who was “being consumed,” to quote Lofton’s phrase. Was it the screaming fans who were consumed by the sheer euphoria of being in the same physical space as a celebrity pop singer? Or was it Bieber, who has been a vocal critic of his own commodification? To answer this question is to reflect on the power dynamics in the arena. Who ultimately has the power: Is it the charismatic performer who is worshipped as a godlike figure, or the fans who are literally objectifying him through their smartphones?

The final chapter of this anecdote is that Bieber quit his Purpose tour because he found a religious purpose and “rededicated his life to Christ.” He joined the conservative megachurch called Hillsong Church, with branches in NYC and LA, where thousands of young people convene for Sunday services (several services offered all day) that combine rock music with prayer and charismatically delivered sermons. The Australian founder of the church, Brian Houston, published the book You Need More Money, and he and other preachers worldwide share their “Prosperity Teachings” based on the fact that God wants his people wealthy. Described by its detractors as an insidious cult called “hellsong” and by its supporters as a trendy “hipster church,” Hillsong unites spectacle and religiosity, with parishioners breaking into dance with the lights dimmed and the strobe lights flickering. Bieber speaks openly about his enjoyment of the service, posting a clip on Instagram with the caption: “Nothing more fun/cool than praising God.”

The Hillsong Church fuses together religion and pop music into a spectacle that resembles Bieber’s own. But the difference is significant. Bieber prefers to be the consumer of spectacle rather than its producer, to be among the worshippers rather than the worshipped. He wants to partake in the rituals of religion, but he doesn’t want to be the totem.

One of my questions at the end of Lofton’s evocative and engaging book is: why is worshipping so pleasurable, whether it is Bieber at his Pentecostal megachurch or his fans cheering at his concert? And are all forms of fan worship equivalent? I am thinking of the recent exchanges on Twitter about Beyoncé’s performance at Coachella, which her fans renamed #Beychella. From words of praise from fellow celebrities such as Roxane Gay to Janelle Monáe to tens of thousands of messages on Twitter, which included videos of young African American girls dancing to Beyoncé in their living rooms, #Beychella went viral. How would the rich vocabulary of Consuming Religion from “vitalizing power” to ritualization inform a reading of a black feminist icon such as Beyoncé in contrast to the Kardashians and Britney Spears?

To account for multiple forms of celebrity worship it would be helpful to revisit Talal Asad’s critique of Clifford Geertz’s essay “Religion as a Cultural System.” In Consuming Religion, Lofton defends Geertz in many ways that are commendable, but as a literary scholar, I want to underscore a key point in Asad’s critique that echoes Edward Said’s central point about the significance of context. Cultural signs must always be understood within particular cultural, historical, and political contexts. Asad’s main critique of Geertz is his ahistorical understanding of culture, that religious symbols exist sui generis without specific contexts. Geertz’s aim, according to Asad, is “to identify religious symbols according to universal criteria” (249). But such an aim ignores the fact that cultural symbols have multiple and conflictual meanings. To illustrate how the symbolic is a contested terrain, Asad foregrounds the “theme of power and religion” and explores the extent to which “power constructs religious ideology” and creates the “preconditions for distinctive kinds of religious personality.”

By foregrounding the theme of power, we can revisit the varieties of religious experience through the lens of intersectional celebrity and a global fan base. Through his emphasis on sociality, Durkheim has given Lofton the tools to do this, and her wonderfully readable and innovative book has given her readers the opportunity to imagine new inventions of self-consciousness that are now coming into being.

4.22.19 | Kathryn Lofton

Reply

A Response to Carrie Bramen

There were so many moments when I knew the dissertation was a disaster. I knew it in the quiet, lonely moments: staring out the window of my Davis Library carrel in Chapel Hill, NC; staring into a half-eaten plate of sesame chicken at Jade Palace in Carrboro, NC; staring at my feet as I walked slowly home from a working group meeting. “This is so stupid,” I would think. “This is such a mess.”

Like a lot of despairing graduate students, the nail on the dissertation-disaster coffin was when I read a book covering some of its territory. In 2003, I started Carrie Tirado Bramen’s brilliant, idiosyncratic, singular book, The Uses of Variety: Modern Americanism and the Quest for National Distinctiveness (2000) and I had to put it down because it was so exactly what I wanted to write that to continue reading it would place me in the Jennifer Jason Leigh role: I would just be lurking in someone else’s authorial life, wishing it were my own.

Only later, when I was standing up with a little less anxious wobble in a subsequent job as a visiting assistant professor would I make it all the way through Uses of Variety and admire it without berating embarrassment. Even then, I saw in that book the fruition of an intellectual accomplishment I could not achieve, namely to show (in the same way Tracy Fessenden would in her 2006 book Culture and Redemption) how the history of ideas has serious cultural salience for the imperial present-day structuring of religion. I began my dissertation wanting to bring life to concepts as Bramen and Fessenden did because the historians and critics I admired had done so, demonstrating the contingency of practice and concept in ways many other intellectuals had somehow subdivided in the bureaucratization of knowledge. If Fessenden demonstrates definitively how “tolerance” was a self-conscious production of high-minded individuals who were anything but, Bramen exposed how the celebration of diversity in America was always more an elite phantasmagoria of plenty than any kind of meaningful reckoning with human variety. “The rhetoric of diversity provides a conceptual crutch, a deus ex machina that saves us from having to grapple with complicated and partisan stances,” Bramen writes in Uses of Variety.

In her first book, then, Bramen shows how the appropriation of social diversity is emblematic to modern ideas of “American” identity. In her response to Consuming Religion she does what she has done in both of her books (please: stop now, and request from your local library American Niceness, which will prohibit you from ever again saying “that’s nice” without knowing the settler colonial truth of Urban Dictionary definitions): she shows through a powerful particular the dynamic of the whole. A mediocre performance by young Justin Bieber is precisely the right subject to continue to assess, as Bramen writes, who has the power in the exchanges of consumer culture. Unlike my own work (that tends to focus on how individual and commodity surfaces maintain their smoothness), Bramen sees how the surfaces we set (celebrations of diversity and nice smiles from subjugated subjects) quickly show their cracks. Bieber isn’t super psyched to be Bieber! when Bramen sees him. But even—perhaps especially—in that “flagrant” disregard for the performance of presence, Bramen “couldn’t help but like” his resistance. She infers that one of the reasons she, we, they might still enjoy Bieber (even in his diffidence) is because we’re just so tired of labor, we take pleasure in someone’s alienation. Watching flinching entertainers soothes our internal blenching at our everyday flat-note hustle.

Bramen rightly returns us to Asad’s famous critique of Geertz, underlining that Asad argued we should look for the situated realities of power rather than stick with Geertz’s flat grammar of signs. I couldn’t agree more. Consuming Religion didn’t make apparent enough that I treat Geertz as primary resource rather than secondary colleague. I point to Geertz not out of admiration, but in order to expose how much his (poor) definition of religion echoes definitions of corporate culture circulated by management gurus and business school professors. I meant to render Geertz (and scholarship on religion more generally) as complicit with, and therefore necessary for, the understanding of corporations in contemporary America. Unlike Bramen, however, I am less thoroughgoing in my admiration of Asad, since I do not find in his work a rich model for contextualizing power and religion. For that I turn to his late, great colleague Saba Mahmood, who established for so many what it would mean to theorize religion and grapple with its “multiple and conflictual meanings” in particular cultural scenes.

Here though I reveal how I got so wound up in graduate school: I couldn’t stop bandying between my own fandom and anti-fandom, loving Bramen unequivocally and denouncing Geertz; adoring Mahmood and belly-aching about Asad. This oppositional posture contributed significantly to my failed dissertation, and my general ennui as a human person trying to fit in a world with certain forms of equipoise. “Queer lives remain shaped by that which they fail to reproduce,” Sara Ahmed writes. “To turn this around, queer lives shape what gets reproduced: in the very failure to reproduce the norms through how they inhabit them, queer lives produce different effects.”

There is something important about self-hatred among graduate students. Important because of the recognized statistical seriousness of the problem; important because anytime people berate themselves in common ways we ought to step back and ask from whence this patterned psychological reflex comes. I don’t mean providing only more wellness resources (though always, yes, we should). I mean thinking about, as Ahmed has done so powerfully, the intimately human wages of institutionalized knowledge production. There are as many forms of thinking about this as there are students thinking in these systems. For me it meant realizing the power of failure as an alternative relationship to the knowledge institutions that credentialed me. This has included, most poignantly and painfully, shifting my terms of adulation and dismissal of teachers, human and on the page. It meant, to borrow from Bramen, that I had to stop treating Bieber as Bieber!, and interpret the boredom on his face. To see the human inside the icon.

When I think about Bramen’s Bieber preferring the role of Hillsong spectator over serving as stadium-tour star, I am moved anew by a person—Bieber—that previous to this reading I could not stand. For me this is the highest accomplishment of criticism: to put before the reader something that disgusts them, and ask whether we can understand our revulsion through some true thing in their reality. I remain a Bramenite, not a Belieber. But it is unsurprising to me that it took seeing the latter better to renew my commitment to the former. We can’t understand any idolatry without a little comparative religions.