Bipolar Faith

By

8.5.19 |

Symposium Introduction

My mother has dealt with chronic migraines for almost thirty years now. It’s an everyday occurrence, well at least almost every day. I know because we talk on the phone on a daily basis. Family and friends, with the best of intentions, plead for her to get up. To go out. To do something. She has to convince them that she can’t. She really can’t. My mom has even told me a few times that her morning headache was so bad, so debilitating, so terrifying, that she thought “that was it” for her.

This “it” that my mom speaks of is a kind of “death-threatening pain” that theologian Monica Coleman describes in a 2011 online interview. Discussing the stigma around mental health for many black people, Coleman recounts the following story:

In the midst of a depressive episode, I had a friend say to me, “We are the descendants of those who survived the Middle Passage and slavery. Whatever you’re going through cannot be that bad.” I was so hurt and angry by that statement. No, depression isn’t human trafficking, genocide or slavery, but it is real death-threatening pain to me. And of course, there are those who did not survive those travesties. But that comment just made me feel small and selfish and far worse than before. It made me wish I had never said anything at all.1

My mom can resonate with this guilt, a guilt that piles on after listening to such overpowering voices. She wants to give up. She’s tried every medicine, every cure. She’s probably seen every neurologist in Scottsdale. She even visited an acupuncturist who was featured in her favorite morning news show. Having been a faithful and devoted Catholic all her life, she gets frustrated because she thinks God is frustrated. Frustrated at her. For what, you ask? For not being able to get out of bed. For not being able to do something, anything. For being “useless.” Yes, she has her “good days,” those days that allow her to play with her grandchildren. But these days are rare. And then she feels pressure to feel grateful for the good in her life, similar to what Coleman describes above. “Other people have it much worse,” my mom constantly tells me. “Why am I complaining?”

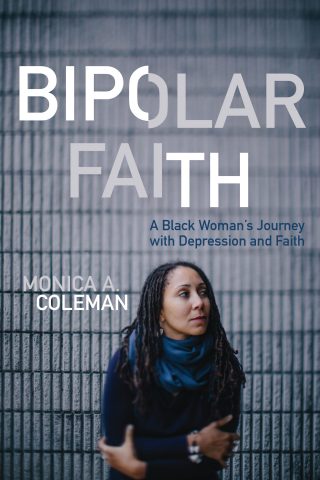

Monica Coleman’s book Bipolar Faith: A Black Woman’s Journey with Depression and Faith is written for people like my mom. By this, I don’t just mean for my mom’s intellectual stimulation, but for my mom’s survival kit. It’s written so my mom can keep going. My mom’s reaction to Coleman’s writing is similar to my students’ when I first assigned Bipolar Faith to them a couple years ago. There was no light bulb that went off, no revolutionary insight that blew their minds. The effect was much more meaningful, more profound than a library of dissertations on the subject. In Coleman’s stories, her words, and her brilliance, my mom and my students found a companion. A companion for an unsteady, uncertain, and scary journey. I’ve never been one to think that a book can change the world. But what I do know is that Bipolar Faith has made my mom’s world a little less lonely.

In the symposium’s first essay, Thelathia “Nikki” Young reads Bipolar Faith as an invitation for people of the black diaspora “to live beyond, not despite, the generational inheritance and tangible effects of individual and collective grief, depression, and trauma.” Praising Coleman’s ability to produce what Audre Lorde called “erotic knowledge,” Young focuses on the book’s call for both a radical honesty towards and a radical refusal of death. “This refusal,” Young writes, “seems to mean . . . developing life-saving rituals.” Young concludes her essay by highlighting Coleman’s “meaning-making map of survival,” and she “honor[s] the ways that Coleman chases livability by navigating the refusal of death.”

The symposium’s second essay features Lisa Powell’s reading of Bipolar Faith, where she explores what these life-saving rituals look like in the context of a white, male, heterosexual world of academia. In a context “surrounded by a disproportionate number of men, taught by men, reading only men,” Powell writes, “it’s no wonder women sometimes become sick.” She finds in Coleman’s work an outlet for which to address the many ways that higher education causes anxiety, stress, and mental illness, but also beats down people with illness (especially as it intersects with one’s race, gender, and sexuality). This includes not being taken seriously as an academic, suffering from an imposter syndrome, and having one’s work rejected for not being “real” systematic theology. “We enter a program of study in service to God, and surrender ourselves to the parameters and criteria of the discipline, but upon entering, find it antagonistic to our perspectives, experiences, and ways of being,” Powell observes. “How do our bodies, our selves, and our faith survive?”

Melanie Webb, in our third essay, draws on Augustine’s Confessions to show how Coleman “exhibits an Augustinian openness to narrative potential” yet rooted in a vastly different confessional tradition—namely that of process theology. Throughout her reflection, Webb uses Augustine and W. E. B. Du Bois to help us understand how artfully Coleman sets up her narrative, even and especially the narrative of her rape. To be sure, what Coleman says matters a lot to Webb, but Webb pays much more attention to how she says it—how, in other words, Coleman “lets her soul speak.” “And as Augustine relies on psalms, so Coleman relies on hymns and spirituals,” Webb writes. “She uses the language passed down by her mother and grandmother; she makes a world with these words.”

In the symposium’s fourth and final essay, John Swinton centers on the recurring theme of diagnosis found in Bipolar Faith. He finds in Coleman’s narrative an account of her “being diagnosed—both by the church and by medicine.” Throughout his response, Swinton addresses the hermeneutical challenges raised by both medial and theological diagnoses. One of the many virtues of Coleman’s writing, Swinton notes, is that she shows how these diagnoses might “be necessary for certain purposes, but they are clearly not sufficient.” After chronicling how “medical imperialism” serves as a sort of epistemic injustice against many patients, Swinton shows how various theodicies play a similar role in religious spaces. Because Coleman resists such imperial and reductionist explanations, he concludes, Bipolar Faith invites both the church and medicine “to listen differently and to hear more faithfully.”

Therese Borchard, “Black and Depressed,” HuffPost, October 15, 2011, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/black-and-depressed_b_926279.↩

Response

A Response to Monica Coleman’s Bipolar Faith

Our livability—the capacity to be and stay alive while pursuing the experience of happiness and liberation—is directly related to the synchronistic, symbiotic, and balanced health of our spirits, minds, emotions, and bodies. Here, I choose to use the plural to signify the depth, necessity, and interdependence of our individual and collective livability, just as Monica Coleman does in Bipolar Faith. “Each component of my life was a connected knot, binding me to other people and practices that kept me alive,” she says (256). As individuals, we most significantly access the possibility of life when we experience such a balance; as a people, we have it when we intentionally work toward, fiercely protect, and continuously ensure the circumstances of livability for and with one another.

Through her heart-in-hand writing approach to theological reflection and process theology, Coleman takes us on a confrontation tour—one which relieves readers of the opportunity to avoid, ignore, or deny the impact of mental illness, relational brokenness, oppression, and trauma on multiple aspects of our lives. Through an agile and graceful dance of introspection, critical narration, social analysis, and spiritual reflection, Coleman invites readers to make room within ourselves to witness and attend to another’s (her) holy work of pursuing life and ongoing livability. In the writing of the text, Coleman compels us not only to think theologically but to feel theologically as well. She blurs the lines between reason and experience, mind and body in a way that allows us to fully engage what Audre Lorde calls “erotic knowledge.” In so doing, we can more fully and honestly nurture our own desire and effort to live beyond, not despite, the generational inheritance and tangible effects of individual and collective grief, depression, and trauma.

Two aspects of Coleman’s book enhance the possibility of such a nurturing for me. The first is her negotiation of relational complexity through the narration of her relationship with her Mama. In fact, one of the most striking lines in the book comes when Coleman reflects on her experience of her mother’s active love as she navigated weeks of “the Illness.”

I have a Mama who stopped her life for six weeks to save mine. . . . She knew how to take care of me. I forgot that. Because she didn’t understand my response to the rape, I forgot. But I knew then. My Mama still knew how to take care of me.” (256)

When her mother traveled to California to feed and nurture her, drive her to class and take notes, Coleman recalled the same mother who decided to save both of their lives by leaving Coleman’s father. Mama, whose response to Coleman’s decision to report the rape emerged from a concern with what people might think and say, responded differently to the illness. Coleman noticed that during the illness, her mother asked her what she needed and gave it to her without judgment or trepidation about others’ assessments of Coleman’s needs and choices. As I read, I considered Coleman’s reflection of the moment to be an important reminder that the sickness that made it so that Grandma could “no longer mother . . . [and] no longer grandmother” was altogether different from the death-dealing Illness that she and her mother barely survived (10). This illness was a bodily response to sadness, depression, fatigue, and loneliness. This illness, as Coleman describes it, was soul-deep.

The second aspect of the book that helps me reflect on our desires and efforts to live beyond grief and depression is a little more difficult for me to name. I’ll admit that it feels patronizing and paternalistic when I say it to myself. But, if Coleman’s book does anything, it calls us to honesty. So, here it is: I am proud of Coleman. I have no right to say it that way, but that’s the feeling that her book evokes. I am proud that she chose life over and over again. It is no small thing to face the depths of one’s own pain and trauma and try, without a clear sense of the outcome, various manifestations of healing. Turning the trope of “strong black woman” on its head, Coleman places herself outside of the value economy of strength and weakness. She situates herself, instead, as a persistent listener to the “still, small voice” that echoes the past, her ancestors, her family, her spiritual comrades, her education, and ultimately herself. While she did not seem to find God in the wind, the earthquake, or the fire—understandably so!—Coleman reflects the ways that she and her loved ones held onto her intention to find and be in relation with God. And, at least in my reading, that intentional refusal was enough for her to survive.

This refusal is a queer process of theological construction. It is Coleman’s refusal to maintain the positivist progression of death, found in the linear logic of trauma-pain-grief-death, which denaturalizes and destabilizes the relationship among them. Through an unapologetic interrogation of linearity and a dismissal of a (theological) narrative coherence that ought to lead to her own destruction, Coleman confronts the nature of inheritance itself. By offering her stories as she does, Coleman helps the reader draw lines between what we take in through our blood and the world around us and what we leave on the threshing floor to wither away and die. In this process, the seeming inescapability of destruction that trauma and depression produce turns into something different: the inescapability becomes the depression, trauma, and death.

When I read the first sentences, I took in a sharp breath . . . and held it. By beginning the book with the unforgiving sharpness of death, focusing on its inevitability and even its justification, Coleman appears to construct a story of resurrection after death. “You can die from grief,” she opens. “You can invest so much of what you need in others that you don’t know how to live without them. . . . I know this because my great-grandfather died of grief” (xv). Yet, after a few paragraphs, I realize that her story is actually one about what it means to benefit from the miracle of and simultaneously hold on to life. In short, hers is not a story of grief-induced death; rather it is a narration of what it means to refuse to die. This refusal seems to mean, for Coleman, developing life-saving rituals (189). It means committing minister-fraud so that you can whisper life into yourself while speaking to others (190). It means pursuing the life of the mind (248), and then healing from the isolating impact of that effort (300). It means therapy in a variety of forms, falling in love, saying goodbye to certain relationships in order to grow, while recognizing the potential of others to help or facilitate that growth. I value this meaning-making map of survival, and I honor the ways that Coleman chases livability by navigating the refusal of death.

8.26.19 |

Response

Whose Story Counts?

Medicine, Theology and the Challenges of Diagnosis

Monica Coleman is clearly one of the leading scholars within the area of theology and mental health. In all of her writings she brings a personal, unique and penetrating perspective to the issue of mental health and mental health care and offers her readers deep insights into the necessity to recognise the complexity of the issues and the deep pain of the experience. In Bipolar Faith she brings new and sometimes quite remarkable insights that emerge from her own narrative of depression. The book is masterful in the way that it winds together experience with theological reflection in a way that shines fresh light on both. It is also deeply poetic and at times quite beautiful. For example Monica’s poignant observation on what it means to cry—“some tears are acceptable”—opens up some fascinating perspectives. It seems that for some, it is alright to cry in the context of worship as you express your awe and wonder at the felt presence of Jesus through the power of the Spirit. But, apparently, it is not acceptable to cry when you are depressed and feeling like the soul of your life has been torn away. She is right, some of us do have some odd spiritual double standards. I wonder where people think Jesus goes when the darkness descends? Are the tears of sorrow that we cry as we search for Jesus in the midst of depression not equally as spiritual as the tears of joy that we weep as we worship and recognise the presence of the Lord? Jesus tells us that he will wipe every tear from their eyes (Rev 21:4). All of our tears are valid and all of our tears are temporary.

As the book unfolds, we finds ourselves drawn into a narrative that is not our own, yet which still manages to find resonance and fit within our emotional and spiritual lives. The ability to draw readers into the depth of a story and wrench out shared feelings, emotions, and experiences in the reader is a mark of a good storyteller. Monica clearly has that gift. I can’t really offer any kind of critique of her work. How could you possibly critique someone’s story? Why would one desire to do so. So other than wondering why, bearing in mind the richness of the narrative and the depth of her trauma, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder seems to become the primary interpretive concept towards the end of the book, I am happy for the narrative to do its own work without my interference. That is not a criticism just an observation and a question. I suspect that Monica has her own theological reasons for taking this position, I just think that the book shows very clearly that there is much more to her experiences than medical diagnoses can really capture, significant as they may be. The diagnosis of bipolar disorder wasn’t always there lurking around waiting to be found. It comes in as a conclusion and a helpful perspective, but it clearly is not an explanation for the things she went through.

There is however one issue that I think it might be helpful for us all to reflect upon, and it does relate to the issue of diagnosis. In Monica’s chapter titled “Diagnosis” she lays out quite clearly the problems and the blessings that diagnosis can bring. It will be worth our while drawing out some of the important points that she makes and infers here as they relate to the book and to the life of the church.

Diagnosis

I’ve been thinking a lot about diagnoses recently in relation to my own work on mental health challenges. What exactly are diagnoses? What do they really explain? Are they helpful re-narrations of a person’s living experiences? Or can they distract us from other stories that may be invaluable for a faithful understanding of caring and being with? I haven’t yet come to a conclusion, but Monica’s reflections on her experience of being diagnosed—both by the church and by medicine—is deeply enlightening. In what follows I would like to offer a few reflections on Monica’s experience of “being diagnosed” within the medical and church communities, and begin to tease out some of the important issues. By using fragments of her narrative I will try to show the epistemological significance of diagnosis for the framing of the experience of depression and in so doing, draw out some medical and theological dynamics that can help deepen our understanding of the practices of naming and the importance of thinking narratively about mental health challenges. Let us begin with two incidents that are described in relation to Monica’s experience of diagnosis; one medical and the other theological. One uses the language of medicine and diagnosis, the other the language of theology and theodicy. Both, in different ways, highlight some key issues that illuminate the tensions within Monica’s acceptance of the explanation of her situation.

The Hermeneutics of Psychiatric Diagnoses

Put simply, diagnosis relates to the identification of the nature of an illness or other problem by examination of its symptoms/manifestations. Diagnosis is a fundamentally hermeneutical project wherein using the knowledge available, we interpret particular sets of experience and come to certain conclusions that fit within our understanding. So, we bring a certain set of experience to the psychiatrist or the pastor. They then interpret these experiences according to whatever framework they have been trained in. Through this process a diagnosis is inferred and ascribed. The problem of course is that when this process has been completed and the diagnosis given, there is a temptation to forget about the original story. The things I have been through are now all explained by this new interpretation and this new name. Bearing in mind the power of Monica’s story, simply to tie all of that down in terms of a catchall medical category just doesn’t feel real. To do so is to lose the power and significance of her story and risk turning her lived experience into pathology and symptoms.

However, diagnoses are first and foremost, as my friend David Finnegan Hosey reminded me recently, stories (if readers have yet to read David’s book Christ on the Psych Ward, it is well worth checking out). They are stories that are based on a re-narration of a previous story. The final version of the explanatory narrative is inevitably determined by the power of the narrator, which is why mental health diagnoses can be tricky. They tend to draw everything into the same re-narration and proceed from there as if that was the only important story that needs to be told. But the diagnostic story is not the only story in town, as Monica’s story so masterfully illustrates. Medical and theological diagnoses may be necessary for certain purposes, but they are clearly not sufficient.

Monica pushes us to look at diagnosis slightly differently. At one point she provides us with this vignette:

I told the nurse that I was sad, tired, and uninterested in eating. She told me that I was depressed and needed medication. In fact, she added, I would probably have to be on medication for the rest of my life. “Can’t I just see a doctor? Isn’t therapy included in my health plan?” The nurse refused to schedule an appointment with a doctor until I agreed. Until I told her I would take medication for the rest of my life. I was desperate, but there was no way I was letting these people give me another pill. Ever. I took my weak sad self home.

This encounter raises fundamental questions about the hermeneutical power of medical diagnosis and the ability of mental health professionals to determine what it is that we are experiencing. “You can only get help if you believe what I believe!” There is no discussion, no other stories allowed; just a statement about how the world really is for you even if you don’t agree. This is medical imperialism at its worst. “You have an illness like any other illness. You will have to take your medication and continue to take it for the rest of your life.” Depression here is narrated primarily as an incurable illness that can only be dealt with by medicine and via medication. But is that really an accurate narration of the situation? As one reads through Monica’s story it becomes clear pretty quickly that whilst biology may be involved in her depression, her social experiences are fundamental to her story. Does it really make sense to suggest that medication can eradicate the significance of our history? Monica’s lament—“Can’t I just see a doctor? Isn’t therapy included in my health plan?”—is basically a cry for her story and her history to be listened to; for the nurse to hear and to recognise that she has a story to tell that cannot be healed by medication alone even if the “symptoms” of her sadness may find a certain kind of alleviation in the interaction of chemicals. It is a cry for the nurse to try to understand that there are many ways in which people’s mental health experiences can be understood and articulated.

At that stage in her story Monica was avoiding taking medication, but not simply because of the side effects. In her perception at that point in time, taking medication was perceived as being forced to make a major change in her identity. She had no desire to become a “chronic mental health patient.” She knew that there were other stories to be told. When eventually she did begin to move towards medication as a viable option, she hesitates:

I held the green-and-white rectangle of pills in my hands. It was a simple question that required a tectonic shift in my own understanding of myself.

As she stands on the precipice of a major change in her identity, her friend reintroduces her to the significance of faith. But the form of faith that he points her towards is different from what we might assume:

You have to have faith,” he insisted. “I do.” I immediately replied. “I don’t think God hates me or anything. I believe in God.” “No. Listen. You have to have faith in the medication. You have to believe it will help you. Or it won’t. You’re going to have to trust this too. . . . It’s not idolatry. If you really believe God is in everything, if you really believe that, then you have to know that God is in the medicine too.”

Theologically I don’t hold the view that would believe that “God is in the medicine,” or that God is in everything. I am not sure that is the best way to articulate the relationship between God and creation. Nevertheless, there is still something powerful about recognising that God can work through the medicine. Depression is a certain kind of pain. Pain prevents us from relating to ourselves, to one another. Pain, as Stanley Hauerwas has put it, is the enemy of community. Having faith that medication can open up new spiritual connections—with God, self, and others—draws the mundane practice of taking medication onto a spiritual plane which transforms this technical human practice into a mode of divine relational healing. Medication may be necessary but it is not sufficient for our healing. There are other stories that need to be told. None of this should be heard as a criticism of mental health professionals. It is however an argument against medical dogmatism and the kind of shortsightedness of those who have a tendency to try to reduce mental health challenges to within the boundaries of a single narrative.

Theological Diagnosis

The practice of diagnosing mental health challenges is not something that is confined to the realm of medicine. One might have assumed that the perfect counter story to the kind of narrative reductionism we have discussed thus far is the gospel. The gospel’s wonderful and transformative story about God who in Jesus and through the power of the Holy Spirit offers love, acceptance, salvation and a place of belonging for all within the coming kingdom. Seems like the perfect answer to reductionism. Jesus the healer promises to end our suffering and heal our brokenness. What better way to re-narrate experiences such as Monica’s? Well, Monica reminds us that she loves and trusts Jesus very much, but his followers . . . notsomuch. Monica tells the story of her encounter with Christian psychiatrists, one of whom just happened to be the mother of her best friend:

[The assessment of the Christian psychiatrist was that] I wasn’t depressed. I was lonely. I just needed better social connections. She recommended a local church I might like. I had a church. I had God. I knew the difference between loneliness and illness. I tried another psychiatrist—the mother of a good friend. She knew I was a minister. She even knew my Nashville church. I began to feel comfortable. As we talked on the phone, I told her about the terrible HMO people. I told her about the woman at the counseling center. I told her that I was looking for a referral for a psychiatrist in my part of town. She told me that I didn’t need a doctor; I needed Jesus. I didn’t hear a word she said after this. I made up an excuse to get off the phone. I tried to be polite because she was my friend’s mother. But no, this was not about religion. The conversation added an hour to my daily crying session. It wasn’t hard for people to understand that? Aren’t I telling people I am sad?

The first psychiatrist did, to her credit, seem to push towards a perspective that recognised that there may be social and relational dimensions to depression. However, again, she simply didn’t listen to Monica’s story. Had she listened she would have known that she loved Jesus and that she was deeply engaged with God’s people even if, at times, that was a hard thing to hold onto. Instead she offers a social model to explain her sadness, as if Monica was somehow incapable of seeing the difference between loneliness and illness. Had she listened to her story instead of writing one for herself, things might have been a quite different.

The second psychiatrist was so deeply immersed in her spiritual projections that she was unable to hear any other story. Worse, by implying that Monica was presently out of touch with Jesus, she engages in what we might call casual theodicy. Casual theodicy is a form of lazy thinking wherein Christians ascribe distance from God, sin, or the demonic to explain the presence of psychological distress. Casual theodicy often ends up blaming the individual, locating the problem firmly outside of the social realities of a person’s experiences and placing it firmly within the realm of spiritual alienation, sin and evil. This way of thinking is lazy because it takes no time and makes no effort to explore the complex processes and experiences that are involved in the development of mental health challenges and the complexity of what it means to move towards healing and understanding. It is not just lazy. It is also malignant. It chooses to point the finger of evil at some of the most vulnerable people in our society. It would be rather unusual if a person was stricken by cancer and a pastor were to suggest that what they really need was not chemotherapy or radiotherapy but Jesus. I wonder what Jesus would do?

Conclusion

The problem with casual theodicists and reductionist medics alike, is that they seek to explain people’s mental health experiences without really listening to or hearing their stories. The beauty and the elegance of Monica’s story as it is laid out in Bipolar Faith, is the way in which it refuses to yield to reductionist explanations—be they medical or spiritual—of what has happened to her. In the end she accepts the necessity for diagnosis and medication, but that acceptance only makes sense as we read the practices of naming and medicating, through her narrated history. Her story helps all of us to see that her depression, like all people’s depression, is multifaceted and multi-storied. Depression needs to be narrated to be believed. But narration alone will change nothing unless there are those around who take the time to listen. Monica urges both medicines and theology to listen differently and to hear more faithfully. And that is a great blessing for us all.

8.12.19 | Lisa Powell

Response

Comment on Bipolar Faith

Katie Cannon calls on womanists to tell their stories: “Anecdotal evidence does a lot to reveal the truth as to how oppressed people live with integrity, especially when we are repeatedly unheard but not unvoiced, unseen but not invisible.”1 She exhorts womanists to “mine” the “biotexts” of the lived experience to communicate the theo-ethical, and in so doing push against the “intellectual colonization” of the institution, which is perpetuated by the “golden-boy-mind-guards in professional learned societies.”2 This is the work of Coleman’s Bipolar Faith; she tells her story and leaves the reader to fill in the critique. Coleman’s book is not an overt indictment of the theological academy or the academic complex, but her vulnerability may be a catalyst to a broader discussion of the spiritual and psychological environment cultivated in academic institutions shaping church leaders, ministers, and professors of theology. It is far safer to speak theoretically about the oppressive structures in our institutions and guilds, than it is to share your experience of it. Telling our stories requires those who are already vulnerable in this white, male, heterosexual context to put themselves at risk professionally and personally. Coleman’s memoire courageously challenges the cult of the mind in academia, as admitting to depression, anxiety, or illness is akin to suggesting you are not fit to the task. Some will assume you don’t have the mental stamina to endure the rigors of “real” or “serious” theological work.

In the comments that follow I do not mean to suggest that the very real biological condition of Bipolar II, and the experience of Dr. Coleman, is just a result of the burden imposed by misogyny and white supremacy in our theological systems and institutions. I would, however, like to engage her experience and offer my own, to spotlight the disproportionate strain placed upon those engaging theology from outside the dominant “norm.”3

It is no shock that graduate students face high rates of depression, anxiety, and mental distress. Studies indicate that PhD students in the humanities and arts fare worst of all.4 Still other studies consider the extra weight of “imposter syndrome,” which is often accompanied with high levels of depression and anxiety, and is particularly prevalent among women and people of color in fields where they are underrepresented.5

Imposter syndrome relates to the assumption often made that these individuals did not earn their position on merit and possibly beat out more qualified white men for the spot because of their minority status in that field. Sometimes these assumptions seep out in passing conversation in the form of microaggressions, such as one I heard from male colleagues in graduate school: “Oh, you won’t have any trouble getting a job; you’re a woman.” At face value, the intention of this statement may be support for the recipient, but it also cheapens her competence and qualifications, and of course it assures the speaker that if he doesn’t get the job, it is because he is a white male.6 Women and people of color in fields dominated by white men carry an extra psychological burden because of these assumptions, feeling that they must constantly prove that they earned their place within a supposed “meritocracy.”7

One study of the experience of students of color in doctoral programs labels this burden the “‘Am I going crazy?!’ narrative.” Students in the study experienced “feelings of racialized and cultural isolation and tokenism” and noted a “lack of diverse epistemological perspectives in the curriculum.”8 They were often the only person of color in class, were discouraged from using “culturally appropriate . . . theories and frameworks,” and were not mentored in the same way as their white peers.9 The students regularly negotiated when and where they should identify the situation and when to “let it go.”10 The result was feelings of “tentativeness, insecurity and doubt,” which often led to self-censorship.11 The “Am I going crazy?!” narrative sounds much like the world women in theology also navigate throughout graduate school and beyond.

Coleman conducted her doctoral studies at Claremont School of Theology in Southern California,12 and although she does not name misogyny or racism in the institution as part of what deepens her depression, the suggestion may lie implicitly within lines like: “My bookshelves with Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker . . . collected dust. The books . . . that nournished the Dinah Project were untouched. I didn’t even read the work by the mentors I garnered at Vanderbilt. . . . Now I hauled around tomes by dead men in my weathered backpack with the Harvard crest. Harnack, Schleiermacher, Kant, Plato, Augustine, Gadamer, Hegel, Dunne, Troelstch, Whitehead.”13 She says she “did nothing but read all day and every day works of dead white men, and secondary literature about them.” She concludes: “It made me sick. Literally” (251).

Once she is diagnosed with Bipolar II and receives medication to help manage it, she realizes medication could deal with symptoms but couldn’t create a support system: “I needed more friends. I needed a church closer than thirty minutes away. I needed activism. I didn’t find that in Claremont. If I wanted to be alive, and stay alive, I needed to move” (294). She decided to leave her residency in the PhD program earlier than typical and move to Atlanta, and although she does not call out the white culture of her PhD program and location, she colorfully describes what awaited her in Atlanta: “urban black culture,” salons that specialized in black hair, concerts by Sweet Honey in the Rock, Caribbean food, cousins, friends, black churches, African dance classes, and a “city full of black people” (298).

My experience as a white woman in theology, who does not have a diagnosed mental illness, is different from Coleman’s. Yet, the experience of doctoral study in systematic theology produced many similar symptoms in my own life. The seminar-style class surely contributed to my insecurity and depression.14 Seminar discussions often diverted on the whim of our most vocal and vehement students, which typically resulted in few female contributions.15 In one a professor awkwardly dealt with this by suddenly announcing the other woman in the class would have a pop quiz that day, a public oral exam in seminar. The following week I was abruptly asked to weigh in on an aggressive debate that wandered far from our assigned reading into books I’d never read.

My first panic attack occurred midway through my first semester, the day before our seminar would devote three hours to reading and discussing my ten-page, single-spaced analysis of Schleiermacher’s doctrine of salvation. I’d never experienced one before. I imagined going into my seminar the next afternoon with nothing, an utter failure, forced to drop out of the program. Somehow near the end of the sleepless night my brain calmed, and I was able to produce something passable for class discussion. But the fear that at any moment my mind would betray me in this way brought a sort of panic all its own for the proceeding months.

I was fortunate to be one of two females in a cohort of five studying systematic theology; the year before only one woman entered systematics, and some cohorts have no women, so it was not unheard of to be the lone female in coursework. In the seminars where we were fortunate enough to have more women, we held abbreviated discussions in the sanctum of the women’s restroom during the fifteen-minute breaks. Here we rapidly and excitedly exchanged ideas, building on each other’s observations, until someone would look at her watch and sigh, and we solemnly returned to the room. Perhaps this was most disappointing during our Theological Anthropology seminar. We were not assigned any women theologians, but long portions from Barth and Aquinas. When a student tried to raise the feminist critique of Barth’s theological anthropology, our professor shut her down with his defense of Barth, claiming such charges are unfair because of his historical context, and defended his decision not to engage this by recounting all the things he personally does for women on campus.

Coleman describes the pressure she felt in her PhD program and her concern that they would find out about her depression: “I wanted to be smart. I wanted to get good grades. I wanted to write a dissertation that made a contribution to my field. I wanted to make them proud. They could not know, they could never know, that something was wrong with my mind” (291). Coleman’s untreated condition gave her insomnia, and the depth of her sleep deprivation left her body depleted; she suffered extended physical illness and a decline of mental acuity. She writes: “I was fearful and ashamed” (297).

My physical symptoms were not as acute, but the shame haunted me, and I tried to hide every sign of weakness; I felt fragile. According to my ophthalmologist, the stress gave me a “lazy eye,” which was causing me to see double. Further, I was a passenger in a serious car accident at the end of my first year, which had me hospitalized for three days with numerous internal injuries and a concussion, followed by weeks on bed rest, which was difficult to accommodate living alone in an isolated PhD program. Fearing the effect of the concussion on my work, or that faculty would assume I’d fall behind as a result, I kept this from them. The following year it was a breast mass, second opinions, and surgery. I kept this private also; I couldn’t make myself more vulnerable, and perhaps I didn’t want to have to mention my breasts. Since our conversations were always restricted to research or teaching, things related to my “personal life” never came up anyway.

I suffered under the weight of dread and fear I would disappoint those people who put faith in me, including my family, but also those who wrote me letters of recommendation and encouraged me in my pursuit of this intellectual life; I was certain I was failing them. I felt shame that I wasn’t actually “cut out” for this, or smart enough. A defensive shell of resentment grew to protect what was left of any belief I had that I could be “successful” in this field or that I had something to offer it.

Relationships with faculty and advisors are commonly cited factors in graduate student distress,16 a situation addressed by post-colonial theologian Susan Abraham. She highlights not only the insufficiency of mentorship like that noted in the “Am I crazy?!” study, but also the actual harm caused in “being mentored by those who refuse to acknowledge their racial, class, gender, sexuality, or religious privilege in the academy,” as this only “serves to deepen the many experiences of alienation.”17 Abraham writes that she received some ruse of mentorship only if she performed to cultural stereotypes imposed upon her as a Catholic woman from India studying and working in the United States. This expectation and lack of true mentorship “became a problem [she] had to overcome emotionally and psychologically.”18

At the end of my first year, my chair asked to be removed from my committee because my research was still concentrated on liberative themes in historical theology, saying: “I assumed you would have grown out of this interest in liberation theology by now.” I intended to follow the advice given me by a respected woman in systematic theology visiting from Harvard who told me to “write a dissertation that will make the boys happy; then write whatever you want.” In the end I wrote on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, hardly making the “boys happy.” When the notice of my dissertation defense was sent out, one professor commented to a member of my committee that he didn’t understand why I chose to write on this woman, as if it were random. Similar comments were made regarding another theology student when she decided to write her dissertation on a woman whose work was not yet published in English, as if it were a shame because she showed such promise. Why are our investigations of the theological contributions of women relegated to a niche subcategory, no longer considered systematic theology?

Perhaps we chose to feature the contributions of women because we needed it for our mental health. After all, female voices were virtually absent from our seminars and reading lists for our “comprehensive” exams, reflecting what was deemed important and relevant, and perpetuating this culture through the future educators trained in this manner. (How do faculty assign copious amounts of reading for seminars and exams and fail to include women and scholars of color, time after time?) In a program surrounded by a disproportionate number of men, taught by men, reading only men—it’s no wonder women sometimes become sick.

I finally sought help, not for depression, but for what I feared was a tumor in my throat when I began to struggle to swallow the softest of food, even soup. I lost weight rapidly. My doctor explained this was not an unusual physical response to extreme stress and put me on an anti-depressant. At the AAR meeting that fall a member of my committee noticed how thin I had become and commented that it may concern potential hiring committees. So I added the worry that committees would think I had an eating disorder or was overly concerned with my appearance and wanted to be this thin. I wonder if skinny male colleagues had to worry about this.

I’m not sure what difference it makes if sexism is overt or simply perceived. The problem pertains to the uncertainty itself—the psychological burden of wondering what comment or lack of engagement is related to your gender—and the stress of navigating these questions constantly. We have to weigh the cost of: drawing more attention to our already troublingly sexed bodies by bringing up an issue when it arises; being punished for playing the “victim card”; or being dismissed as one whose work focuses on women and thus isn’t rigorous or relevant to the discipline as a whole. Even now nearly ten years beyond graduation, though it has lessoned, these nagging question emerge around student comments, speaking invitations, and so on. Katie Cannon says, “We often wonder if our experiences . . . are peculiar to the religious academy or if these are general patterns of misogyny practiced in other fields of study where women have been traditionally barred, such as in medicine and law.”19 We often wonder.

Four years into my PhD program, deeply distressed, I could not pray anymore. The only God I’d known was now identified with their God, the God debated in bombastic and combative tones, the God of those who drowned out the voices of women around the table. I was begging for help from a God for whom these people were the gatekeepers, and I couldn’t trust “Him.”20 I couldn’t cling to this God in my broken vulnerability, but I didn’t have another God to whom to turn. It has taken years to wrench the God of my faith away from the possessive grip of the guarders of conservative orthodoxy, to rebuild trust in God and reconstruct my love of the Christian faith through the work of Cone, Gutierrez, and Kwok Pui-Lan.

Theology is perhaps unique among academic disciplines in that the task is typically related to the core identity of the theologian. It is discourse around one’s life-centering purpose and object of devotion. It touches to the most tender parts of a person’s belief system.21 As Coleman vividly illustrates from her own experience, for many God is the one we turn to in crisis, in our need, and in suffering. What happens when we experience the system around this God-talk as one that bombards us with messages that we aren’t good enough, don’t belong, or that the work produced by people in our communities isn’t a significant contribution to this conversation? What does the context of theological education do to one’s spirit and psyche when “the masterminds of intellectual imperialism encode our candid perceptions and scholarly labor as nothing more than culturally laden idiosyncrasies”?22 We enter a program of study in service to God, and surrender ourselves to the parameters and criteria of the discipline, but upon entering, find it antagonistic to our perspectives, experiences, and ways of being. How do our bodies, our selves, and our faith survive?

Katie G. Cannon, “Structured Academic Amnesia: As If This True Womanist Story Never Happened,” in Deeper Shades of Purple: Womanism in Religion and Society, ed. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 21.↩

Cannon, “Structured Academic Amnesia,” 25, 22.↩

See Anne Joh’s article for AAR’s “Religious Studies News,” May 2014, on doctoral studies and institutional whiteness, https://www.aarweb.org/publications/rsn-may-2014-on-diversity-institutional-whiteness-and-its-will-for-change. My reflections here revolve around a few questions that seem to emerge quite frequently in doctoral studies, especially from students of racial/ethnic minority communities and what institutional racism does to them during the process of going through a doctoral program. How are the needs of these students met or not met within the predominantly white institutions and programs whose curricula often reflect absence and foreclosure of the historical legacy of systemic racism? How can institutions committed to cultivating institutional diversity transform so that all students might thrive during their studies, become well prepared to enter their profession as educators.”↩

One study cites depression rates among humanities and arts at 67% compared to 43–46% for biological or physical sciences and engineering, 34% for social sciences and 28% for business. The same study found 10% of graduate students admitting to suicidal thoughts (http://ga.berkeley.edu/wellbeingreport/). The University of Texas at Austin studied stress and graduate students, and found that 43% of graduate students reported experiencing “more stress than they can handle,” with the highest rates among PhD students specifically. They also found the highest levels of stress in the humanities and arts, where it was over 50% of students (http://gradresources.org/research/).↩

http://www.paulineroseclance.com/pdf/ip_high_achieving_women.pdf.↩

This fallacy regarding the hiring of women and minorities in theology may be exposed by looking at the percentages of faculty members. For example the percentage of women faculty at ATS-accredited schools has seen only a small increase in the last twenty years. According to ATS in 1996, around 20% were female. (https://www.ats.edu/uploads/resources/institutional-data/fact-books/1996-1997-fact-book.pdf). In 2016 the number is around 25% (https://www.ats.edu/uploads/resources/institutional-data/annual-data-tables/2016-2017-annual-data-tables.pdf). Women account for between 45–50% percent of bachelors and masters degrees in religion and nearly 40% of graduates with PhDs in religious fields, and yet the percentage of women on faculty does not reflect this (https://www.ats.edu/uploads/resources/publications-presentations/colloquy-online/women-in-ats-schools.pdf). The increase over the past two decades of supposed affirmative action hires in theology is slim.↩

http://college.usatoday.com/2017/04/24/study-impostor-syndrome-causes-mental-distress-in-minority-students/.↩

Ryan Everly Gildersleeve, Natasha N. Croom, and Philip L. Vasquez, “‘Am I Going Crazy?!’: A Critical Race Analysis of Doctoral Education,” Equity & Excellence in Education 44.1 (2011) 93–114, quoted here at p. 95.↩

Gildersleeve et al., “Am I Going Crazy?!,” 95–96.↩

Gildersleeve et al., “Am I Going Crazy?!,” 103.↩

Gildersleeve et al., “Am I Going Crazy?!,” 100.↩

Coleman now serves as professor of constructive theology at Claremont School of Theology.↩

Monica Coleman, Bipolar Faith: A Black Woman’s Journey with Depression and Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2016), 248, 249.↩

In an article for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Kate Bahn cites the seminar culture as part of the problem for many women in academia (https://chroniclevitae.com/news/412-faking-it-women-academia-and-impostor-syndrome).↩

An exception to much of that described here is Ellen Charry’s Cappadocians seminar. I should also note that Mark Taylor was on sabbatical when his seminar would have been taught, and so he did not offer it during my coursework.↩

See Gildersleeve et al. for a summary of research citing this as a factor.↩

Susan Abraham, “Mentoring (In)Hospitable Places,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 33.1 (Spring 2017), 123. She proposes a “feminist co-mentoring” because “traditional mentoring is not equally accessible to all groups within academia, and members of dominant groups—white, male and heterosexual receive more benefits from traditional mentoring relationships than underrepresented groups.” Here she is quoting Gail McGuire and Jo Reger, “Feminist Co-mentoring: A Model for Academic Professional Development,” NWSJ 15.1 (Spring 2003) 54–72, quoted here at p. 59.↩

Abraham, “Mentoring (In)Hospitable Places,” 121.↩

Cannon, “Structured Academic Amnesia,” 22.↩

The pronoun “him” and “he” were used in abundance throughout these seminar debates, of course.↩

Other disciplines may share some similarities: critical race studies, gender and queer studies, disability studies, etc.↩

Cannon addresses this from the perspective of theological education itself: She concludes that “we end up with education that is unbalanced, knowledge that is incomplete, and a worldview that is distorted” (27).↩

8.12.19 | Monica Coleman

Reply

Response to Lisa Powell

Lisa Powell finds the story I did not tell. She finds the traces of it where it seeps out in the cracks of the story I was trying to tell. Because, of course, the experience of racism and sexism and ableism within the academy—the theological academy—is woven into the fabric of my professional and personal life. The threads are so fine, sometimes, I forget the colors they add to the tapestry.

When I first read Powell’s reflection, her notations felt tangential to Bipolar Faith. Yes, I escaped what felt to me like the God-forsaken context of Claremont Graduate University and Claremont, California. Yes, I read the philosophies of so many dead white men. But that was not the story of depression I was trying to tell. That was the context of one section. Oh, but Powell is right. The dominance of dead and near-dead white men is the context of higher education, of the academy, of the wider world for many women and many people of color. Our histories and perspectives are overlooked; our classroom contributions largely ignored. We are socialized, taught, and justifiably afraid to be vulnerable. We want, at least I wanted, to learn and to show that I could philosophize with the rest of them—the white men. Learning and living and trying to succeed in that kind of atmosphere shapes who we are, and at best, does not ease any stressors, and at worst, facilitates, deepens, and causes anxiety, depression, and more overtly physical ailments.

So if there was anything fueling my silence and deepening my experiences of depression, it was knowing that there is what Powell names as “the cult of the mind in academia,” and that “admitting to depression, anxiety, or illness is akin to suggesting that [I am] not fit to the task.”

Powell names the biotext of Bipolar Faith as womanist work à la Katie Cannon’s naming. Cannon’s recent transition to ancestor status only intensifies the honor of this description. Cannon was to me, as she was to so many, an encourager. She sent handwritten notes of congratulations for every academic milestone. She welcomed me into womanist religious scholarship in theoretical and tangible ways. She encouraged me to furnish the “womanist house of wisdom” that she and her generation of womanist scholars struggled to build. She invited me to discuss the joys and challenges of teaching. She, and her mother, drove from her corner of North Carolina to my corner of North Carolina so that she could talk with my students. And Katie Cannon told the story of how she encountered racism and sexism and how it completely changed the course of her academic career. Her harrowing, difficult, unjust, field-innovating journey gave us black womanist ethics.

By the accident of age and exposure, I found Cannon’s writings. And James Cone and Gayraud Wilmore and Renita Weems and Sallie McFague and Rosemary Ruether and Majorie Suchocki. I found their work before I knew about Barth, Whitehead, Bultmann, Nietzsche, and the boys. So I knew that black women had their own theologies and perspectives in religious studies. It was their writings that lured me to the religious academy. On the one hand, it made the European philosophers more shocking. On the other hand, I knew that they were not the end of religious reflection—only a route to the road I wanted to walk.

Powell reminds me of the parts of my story I hint at, but did not tell. I did not mention how I constantly combined sass with loneliness and what Cannon calls “unshouted courage” to assert my right to be the only black woman in classrooms of fifteen white men, one Asian man, and two white women. That was what coursework looked like for me. Or how I rapped on the door of the one black woman faculty member and asked to sit in her office because no, I don’t need anything, but I just need to hear the cadence of your voice and the rhythm of your gait to feel a little less alone. Upon learning that I was clergy, classmates with one graduate degree less than I treated me as if I wasn’t qualified to study philosophy, and so I wore my Harvard backpack to class as a silent way of sliding my credentials across the table. “I see you and raise you,” I thought. I wrote about West African religion and black women’s science fiction and popular African American religious leaders in my classes on dead white men’s philosophy. These acts were designed to say: “I belong here. This is my field too.”

I never felt that the white maleness of my field contributed to my illness. It’s always been the backdrop in which I’ve lived a public life. Elementary school, high school, college, divinity school. My early childhood lessons on race and humanity contained admonitions from my parents about what Langston Hughes calls “the ways of white folk” and the kinds of overqualification I would need to receive “half as much.” Negotiating white male space is an endemic part of being a living black woman. Did it make me sick? Inasmuch as it makes all black women sick. Or perhaps the better term is “tired.” Because we’ve been doing it for so long. I knew that there was no safety to be found in a place not made for my survival. I did not look to schools or academic programs as safe havens. I came to each with a level of racialized and gendered skepticism. I barely believed my faculty were on my side. It took years for me to see them as allies. I tried to portray them as such in Bipolar Faith.

So, Powell reminds me of my micro-resistances. That I took steps everyday, in little ways (and sometimes in big ways) to assert my humanity, my merit, my intellect, my sanity. Powell reminds me that I long had these taught-and-learned modalities: a small group of tightly-knit friends, music, dancing, church-attendance, extended family, black culture, women’s circles. And when a context did not serve me, I left. I left so I could have some space of acceptance in the desert of white-male-academy. I left to various oases. The oasis of blackness in Atlanta, of feminist Christianity in Circle of Grace, of cousins and music and food that nourished and sustained me while I spent my days in the stacks with the books written by men who died decades before. That was how I answered Powell’s question: “How do our bodies, our selves, and our faiths survive?”