Phantom Africa

By

3.18.19 |

Symposium Introduction

Brent Hayes Edwards’s monumental translation of Michel Leiris’s puzzling, infuriating, and thoroughly fascinating Phantom Africa makes available to a new—and newly critical—generation of students and readers a crucial document of colonial ethnography with profound import for literary history and modernism and surrealism in particular. Originally published in 1934, Phantom Africa is as generically wild as it is ideologically fraught, veering from essayistic critiques of the imperial object-gathering enterprise in Africa to rapturous fantasias that imagine cross-cultural knowledge-gathering in terms of radical eroticism and psychic revolution.

In the simplest terms, Phantom Africa is an impressionist’s diary, written by a man disillusioned with the literary culture of Paris, and recounting in granular detail his experience of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti (1931–1933), financed by the French government as its first ethnographic expedition in sub-Saharan Africa. As the mission’s “secretary archivist,” charged especially with documenting each object requisitioned as booty for display in Paris, Leiris was both faithful to this mission and deeply invested in his own position as an outsider to it, oftentimes in what now read as unappealingly heroic and salvific terms. At the same time, the book is marked by a desperate and accelerating sense of melancholy, a growing conviction that the cultural and linguistic abyss between the European observer and the Africa he is charged with grasping is too wide, too cavernous, and too ontologically destabilizing to bridge. There is also the tedious reality of bureaucratic travel: “All these days remain hollow,” Leiris writes, “my motions are purely mechanical. Again, I am being driven to hate my companions.”

Given the purpose of the mission, one doesn’t have to venture many guesses as to why. In preparation for his journey, Leiris writes of the “white mentality” that perceives everything other “in an entirely phantasmagorical way.” Displacing this mentality is, for him, a way to “undermine . . . racial prejudice, and iniquity against which one can never struggle enough.” Phantom Africa, and the non-specialist ethnography it both invents and records, attempts to reckon with this habit by way of a strict empiricism turned most energetically on the writer himself. The journal is infused with Leiris’s own sense and obsessive tracking of the observer’s subjective particularity. Like a latter-day Montaigne, he writes of his heartburn, his Rabelaisian lunch. And his own reflections become, in the later prefaces to the work, the subject of his scrutiny once again. As Justin Izzo suggests in his response, “What results is a mise en abyme of selves, different versions of Leiris (Leiris 2.0 or 3.0, we might say) who critique the political positions of earlier iterations and cause the journal’s original self to recede and become phantomlike.”

These moments and meta-moments within and between the publications of the text confess the science’s non-objectivity a form of accusation, illuminating the mission’s total co-optation into the projects of imperial resource extraction. Nevertheless, the “Africa” that appears in these pages is stubbornly ghost and ghosted. As in many earlier travel narratives attached to the requisition and management of far-flung territories, the epistemic interval Leiris constantly confronts and attempts to bridge amplifies what Amiel Bizé calls in her essay “ethnographic desire”—a “passion” “for speaking of what he does not know,” the “ethnographic bug” that bites him. For Bizé, this desire, offered in the mode of confession, both motors the narrative and constantly threatens to undo it.

Edwards’s introduction and apparatus illuminate these tensions and problematic self-positionings in ways that will be and already have been incredibly productive for students and scholars of imperial and literary history. In this way, Edwards’s Phantom Africa is a gift not only to an English-language readership, but to anyone interested in Leiris’s legacy and the discursive history of a continent that—in the hands of its Western observers—is continually and purposely made to fade from view. Leiris was not the first to stage such an erasure in the terms of keenly documented unknowability—what Keugro Macharia refers to as scholars’ cynical deployment of “the problem of the inexpressible, the untranslatable, the undecipherable, and many other negating prefixes: in-, un-, de-, imp”—nor would he be the last. As Chinua Achebe notes in his indelible repudiation of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the modernist and surrealist canons in particular trade in the coin of obscurity and obfuscation when it comes to Africa. For Achebe, Conrad is “engaged in inducing hypnotic stupor in his readers through a bombardment of emotive words and other forms of trickery.”

Particularly enriching is Edwards’s inclusion, as beautifully laid-out sidenotes, of Leiris’s letters to his wife, Zette, with whom he corresponded voluminously during the mission, his mother, and more—Amah Edoh rightly called the decision “inspired.” The letters offer a valuable and fascinating picture of the literary and observational decisions that shaped Phantom Africa, peculiar as the outcomes or these writerly choices may be in generic and tonal terms.

Vast, uncomfortable, historically essential—the appearance of this work in English almost a century after its publication raises fraught disciplinary and affective questions for its readers. In addition to Bizé’s useful meditation on ethnographic desire, and Izzo’s reflections on Leiris’s ontology and the limits of contemporary discursive barrier policing between literature and anthropology, this dossier contains perspectives that foreground in affective terms the challenge of reading a text as “new” in a present in which the arrogance and racialized injustice in and behind Leiris’s writing is nowhere near eradicated. Kaiama Glover’s essay frames these issues in terms of spatial, temporal, and linguistic translation, beginning of course with Leiris’s own project of translating what he saw and what he heard for the mission and for the broader readership he imagined. For Amah Edoh, “Phantom Africa brought about (to my dismay!) moments of intense recognition and resonance . . . the overwhelm; the beginner’s faith in the promise of ethnographic research as a mode of and means to definitive knowing” but also ambivalence, “points of disjuncture” that are “momentous.”

Chinua Achebe, “An Image of Africa,” 1785.↩

3.25.19 |

Response

The Moment of Translation

But at the moment of translation, everything is ruined.

—Michel Leiris, Phantom Africa (October 11, 1931)

I

Multiple and complex layers of translation separate the colonies and sovereign nations across the African continent Michel Leiris traversed in the early 1930s from the early twenty-first-century English-language reader of Phantom Africa. These layers are both temporally and spatially consequential. Between 1931 and 1933, several more-or-less competent and more-or-less willing African interpreters translated their world to Leiris, helping him to perceive, in real time, truths that otherwise would escape (and often nevertheless did) his French European eyes and ears. Largely reliant on these interpreters throughout his journey, and constantly frustrated by what he knew to be their insufficiencies, mocking deceptions, and willful refusals, Leiris sought to transcribe—also in real time—all that he “understood” into his journal. Thus did he set out to translate the accumulated experiences of his travel across the African continent—along with the African languages and cultures he encountered there—for a metropolitan French readership, endeavoring mightily all the while to avoid what Edwards calls the “inevitable distortion” (5) of exoticism.

Of the many fascinating dimensions of this process, one of the most compelling is the extent to which it hinges on the impossible bind of Leiris’s desire-effort to translate Africa. It is crucial to understand the mission as a whole as an ambitious overarching experiment in cultural translation. Ten Frenchmen sought to apply their diverse skills and competencies to making black Africa legible to white Europe. In effecting this translational process, they relied fundamentally on countless, punctual moments of interpretation wherein they could not be entirely sure to have understood anything essential or, at times, even true.

Leiris makes numerous references to his frustrations in the face of translational impossibility. Because he was so meticulous in reporting his interactions with his African interpreter-interlocutors, we readers bear witness to the sustained tension between Leiris’s desire for information that would reveal to him the human truth of the people whose world he temporarily inhabited, and the wariness of those people and/or their interpreters in trusting him with this information. This was, of course, the central bind of the entire expedition, and it saddened and enraged Leiris in equal measure.

Leiris’s affective response to the limits of translation and of his translators—his annoyance and resentment, his anger and his suspiciousness—expose the limits of his self-awareness at the time of the mission and suggest also the limits of the project as a whole. If, that is, a stated objective of the Mission Dakar-Dijbouti was to reveal and record—to translate—the humanity of the African “Other” to a European scientific audience, that objective required knowledge of the “Other.” It required comprehension in its most rooted sense—as understanding, yes, but also as a means of completely taking hold of or seizing.

II

In this respect, Phantom Africa recalls another important mid-century French text that similarly sought to intervene in metropolitan-colonial relations and that similarly turned around questions of visibility and power: “Black Orpheus,” Jean-Paul Sartre’s preface to the 1948 Anthology of New Negro and Malagasy Poetry in French, compiled by Negritude poet-philosopher Léopold Sedar Senghor. Given that “Black Orpheus” is nearly fifteen years Phantom Africa’s junior, there are ways in which it may be anachronistic to compare the two. It is true that at the time of the mission Leiris had not yet come around to an explicitly anti-colonialist politics and that he was, in 1934, a far less sophisticated thinker of race and imperialism than Sartre. Nonetheless, the stakes underlying the two texts—the question of Europe’s imperial gaze, colonial resistance to that gaze, and the ambivalent positioning of the progressive French intelligentsia in the face of these changing dynamics—are remarkably similar. Phantom Africa and “Black Orpheus” exist on a continuum of European male (the question of gender is crucial and is taken up below) attitudes toward and presumptions about nonwhite subjects that are firmly anchored in the relational hierarchies of colonialism.

The series of provocative question-declarations Sartre puts forward in the very first paragraph of “Black Orpheus” interpolate a white readership that he at once admonishes and acknowledges as his geopolitical kin:

When you removed the gag that was keeping these black mouths shut, what were you hoping for? That they would sing your praises? Did you think that when they raised themselves up again, you would read adoration in the eyes of these heads that our fathers had forced to bend down to the very ground? Here are black men standing, looking at us, and I hope that you—like me—will feel the shock of being seen. . . . Today, these black men are looking at us, and our gaze comes back to our own eyes; in their turn, black torches light up the world and our white heads are no more than Chinese lanterns swinging in the wind. (13)

The remarkable pronominal instability that runs throughout this introductory paragraph attest to Sartre’s self-positioning as liaison-interpreter. And as he proceeds in his pronouncements on the black poetic imagination, it becomes apparent that he is caught in a bind not dissimilar to that which underpins Leiris’s narrative. It is the bind Frantz Fanon, writing critically about “Black Orpheus,” identifies in his fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks (1952), notably, the extent to which the role of sympathetic European intermediary-translator is de facto and inevitably corrupted by the relations of power that mark the colonial era. The European’s right and capacity to know is never disputed, nor is the presumption of universal human movement toward a common goal; Europe’s desire to com-prehend through a rendering transparent of the Other—through a translation of the Other into French metropolitan terms—stands as the legitimate and ultimate objective. That is, while Sartre begins “Black Orpheus” with a forceful claim for reversing the colonial gaze and accepting “the shock of being seen,” he nevertheless proceeds to define “Negro poetry.” He frames his translation within a Hellenic myth and then concludes by coopting black aesthetics into Hegel’s formulation of dialectical materialism—i.e., a universalizing German philosophical conceit.

To consider Leiris’s ambivalent narrative alongside the blind spots in Sartre’s categorical denunciation of white supremacy provides insight into the emotional contours of Leiris’s engagement with the African interpreters and translators he relied on during the mission. More than anything else, Leiris wanted to know—to com-prehend Africa and its people both broadly and in their specificity. This was his principle preoccupation, personal as well as professional. He wanted to understand Africa not merely for the sake of science, but in the interest of empathetic engagement. As Edwards notes, and as is evident throughout Phantom Africa, Leiris was interested foremost in the “human significance” of this African adventure. For reasons genuine if condescending, Leiris sought to appreciate and to document the humanity of the people he met. Yet, from the very outset, the extent to which Africa would remain “ultimately unknowable” (52) made this a near-impossible task.

Within just a couple of months of being on the expedition, Leiris was confronted with the limits of his understanding—with the firm and deliberate impediments to carrying meaning across the barriers of language and culture.

Such instances of mistrust, if not downright conflict, between Leiris and his “native informants” were numerous. Some of them, Leiris seems to have taken in stride: he acknowledges, for example, that “the natives often pass off as casual amusement something whose religious purpose they wish to conceal” (note to letter dated July 22, 1931); or, later, “it seems we are making little headway and the people, though they give up little secrets, carefully hide the essentials” (October 3, 1931). Others, he did not: “Livid with rage at a man who shows up to sell grigris and who, when I ask him the magical formulas that must be recited when using them, gives a different version every time I make him repeat one of them so that I can write it down, and, every time that one is to be translated, gives even more new versions” (September 27, 1931). Indeed, there were limits to Leiris’s tolerance for being kept in the dark. And in such moments, his patience sorely tried, he recognized just how unlikely it was that he would achieve any of the noble humanist objectives he had set out for himself. “On reflection,” he writes of an exchange with the father of an informant, “this all seems very artificial to me. What a sinister comedy these old Dogon and I have been playing! A European hypocrite, all sugar and honey, and a Dogon hypocrite, so trite because so much weaker . . . will not be brought any closer by the exchange of fermented liquor. The only link there is between us is a common duplicity” (October 4, 1931).

Despite his best efforts to contextualize his interlocutors’ stonewalling and misinformation, Leiris nevertheless could not help but take personally such failures of translation: “I despair of ever being able to get to the bottom of anything. Merely to have bits and scraps of information concerning so many things infuriates me” (October 5, 1931). Unable to abide an African humanity that might not only be illegible to his European consciousness but that might insist on and defend its illegibility, Leiris experienced these encounters as instances of treacherous translation. Beyond frustration, Leiris on many occasion felt betrayed: “I have been duped,” he rages, “furious and mortified” (October 28, 1931), “old Ambibe has lied to me from start to finish of my work with him, giving me a mass of details, certainly, but deliberately withholding the essential things. I could almost wring his neck” (October 30, 1931). Begrudging, ultimately, the limitations of the privileged metropolitan gaze, Leiris’s expectation of transparency, and the extremes of depression or outrage that ensued in the many instances of its unlikelihood, show just how and to what extent “translation (as a form of mediation between Europeans and Africans) is complicit in the exercise of colonial power,” as Edwards points out (46).

III

It is unsurprising that, faced with these instances of transparency refused, Leiris imagined sex or romance as the sole space of immediacy available to Africans and Europeans.

In this respect, there is yet another “colonial” text that sheds light on Leiris’s desire for translation of the non-European Other, one even more contemporaneous with Phantom Africa than Sartre’s essay: the 1935 feature film Princesse Tam-Tam. A striking example of interwar era colonial cinema, the film’s premise parallels the original impulse behind Leiris’s participation in the mission, that is, the quest to discover in Africa the purpose and passion that had been diminished in the Parisian metropolis. Princesse Tam-Tam tells the story of Max de Mirecourt, a Parisian novelist with a severe case of writer’s block. De Mirecourt is convinced that the life he leads in the capital with his party-hopping, socialite wife has drained him of all creativity, and so he has run away to Africa in search of inspiration. He finds what he needs in the person of Alwina, an impishly alluring and childlike shepherd girl played by world-renowned African American entertainer Josephine Baker. De Mirecourt proceeds to involve Alwina in a suite of adventures and misadventures, of fantasies indulged and disappointed, but ultimately leaves her to her mystifying and incontrovertible otherness—to her Africa—amongst the squalor and simplicity of her animals, unchanged by their encounter. He returns to Paris and to his beautiful blond wife, his love affair with both resurrected by his flirtation with the Other and, more importantly, his fortune assured by the success of the novel he writes based on his African journey.

Like the fictional de Mirecourt, Leiris had left to Africa bored and largely disgusted by the vie mondaine of 1930s Paris, and “increasingly riven by depression and anxiety” (4), as Edwards notes. Heady with African American music and “the ritualistic qualities of black culture” (6), like many of those in his Negrophilic intellectual circles, Leiris sought a dramatic change in environment that would facilitate an equally dramatic change in his personal relationship with a world he increasingly disdained. He was hoping to find, in other words, a cure for his misanthropy.

For the most part, Leiris was frustrated in this objective. Yet there is a way in which Leiris’s African experience mirrors the successful failure of de Mirecourt’s, right down to the unconsummated infatuation with a brown damsel in distress and subsequent return, one manuscript richer, to France and a French wife. Specifically, during the last leg of the mission, the period of engagement with the Abyssinian zar possession cult, Leiris found himself hopelessly captivated by a zarine named Emawayish, “who wants to go to Europe, or at least to Eritrea” (August 24, 1932). “Completely devoted” (August 26, 1932) to her, he indulged in a platonic sort of courtship, attempting to get to know her, bringing her gifts, and otherwise trying to improve what he perceived to be her tragic circumstances. As time passed, however, he became increasingly disillusioned—from believing that she alone allowed him to be “morally reconciled” (September 21, 1932) to a point where, not only was he “no longer dazzled” (October 31, 1932), but where her behavior made him “feel disgusted” (November 8, 1932).

Ironically, however, it is through this gradual disenchantment that Leiris arrived at a victory not unlike that of Princesse Tam-Tam’s de Mirecourt. Disillusionment became liberation: Leiris found himself freed, like de Mirecourt, to fall in love with his wife again—“I’m looking forward to hearing some jazz and going dancing with you when I get back. . . . When I get back, we’ll have to have fun, to dance. With you I’ll have to lead the life of a sailor finally back on solid ground” (letter to Zette, November 28, 1932)—and to return to Paris and the literary life, certain now that he had not been missing anything elsewhere. Like de Mirecourt, he came back to embrace Europe’s promise, cathected in his beloved, who, as Edwards notes in the concluding passage of his introduction, was in many ways the motive force behind his entire enterprise of journaling and self-searching. Like de Mirecourt, he came to see Africa as “poetry probably not quite as beautiful as [he] had believed” (September 1, 1932).

This said, and in a way not dissimilar to Sartre’s claims regarding the “Negro’s” capacity to rejuvenate a soulless Europe, Leiris ultimately did get what he needed from his journey across Africa. He got his mojo back. And he got a book out of it, albeit one that would be neither read nor appreciated by those it translates. Though unable to cross the barriers of culture and consciousness that would have engendered true empathy and understanding, Leiris was unblocked where it mattered. The Africa he encountered in its rawest form worked its magic on his European soul.

From the Latin com- [altogether] + prehendere [to grasp].↩

Leiris’s investment in the Mission Dakar-Dijbouti is greatly informed by his intention to render African cultures less opaque so to protect them effectively. If these cultures are better seen, appreciated, comprehended, perhaps they will not be subjugated, destroyed, pillaged. As Leiris explains in a letter to his wife, “the notion that anthropology had a usefulness that was in some sense moral led to the belief that, since the ends justified the means, there were some situations in which it was permissible to do almost anything in order to obtain objects that would demonstrate, once they were installed in a Parisian museum, the beauty of the civilization in question” (letter to Zette, September 12, 1931). Though this motivation, and the dubious practices it allowed, stand firm, Leiris nonetheless was aware of the paternalist paradox he had advanced: “I have the strong impression that we are going in a vicious circle: we pillage the Negroes under the pretext of teaching people to understand and appreciate them—that is, ultimately in order to mold other ethnographers who will go in turn to ‘appreciate’ and to pillage them” (letter to Zette, September 19, 1931).↩

“Translation is, etymologically, a ‘carrying across’ or ‘bringing across’: the Latin translatio derives from transferre (trans, ‘across’ + ferre, ‘to carry’ or ‘to bring’).” Christopher Kasparek, “The Translator’s Toil,” Polish Review 28.2 (1983) 83.↩

“Immediate” as in im-mediate, as in not mediated—without translation.↩

4.1.19 |

Response

On Ethnographic Desire

I have as little taste as I have talent for speaking of what I do not know, and the only thing I know well is myself.

This, from the entry of April 4, 1931 in Michel Leiris’s Phantom Africa, is as much example of Leiris’s tendency to contradict himself as of his confessional style. Leiris seeks repeatedly to position his journal as a reflection on its author more than as a commentary on “Africa”—since, as he tells us in the book’s title and in its preface, the continent presented in his journal is no more than a phantom. This has been taken as a forward-looking acknowledgment of the role of subjectivity in knowledge production. And indeed, it is a valuable counterpart to ethnographic work of the time, both because it depicts the conditions of that work and because it presented the possibility of a form of writing about “the other” that was more doubtful about the nature of identity or self and its relationship to otherness.

But the journal’s confessional mode operates to obscure as much as to reveal. In positioning his writing as being primarily about the search for himself—the elaboration of an individual subjectivity—Leiris opposes his approach (“half-poetic, half documentary”) to “objective” science with its detached view. But by “confessing” his subjectivity Leiris also holds it up as a shield obscuring the fact that he is very much—even obsessively—involved in the project of documenting otherness. How exactly, then, does “subjectivity” work here? I want to think about this through the lens of ethnographic desire, in order to try to articulate what may be misleading about the opposition of subjectivity and objectivity, or even literature and science. In fact, the obsessive form of Leiris’s narration reveals what his own analysis cannot—the ways in which he is drawn into the mission’s project.

Leiris clearly has a taste for speaking of what he does not know. More than a taste, a “passion,” one of his preferred words. It is clear from the early pages of Phantom Africa that Leiris is smitten with ethnographic desire; he wants to know—not himself, but the other. In his descriptions of his work as part of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti, Leiris writes of a quest for knowledge that waxes and wanes like lust, fed by an attraction to precisely that which is not himself.

Sameness bores Leiris. His initial impressions of the mission are that it is an “insipid activity” to go to another continent in order to “buy in a systematic fashion” the “work tools” of people who are “hardly any more interesting in the end than the residents of Auvergne or any other lost countryside” (98). But after seventy or so pages in which he frequently bemoans his disappointment at realizing that he will not be able to escape himself through encounter with the other . . . the other appears. The ethnographic bug bites. As the mission prepares to leave for Dogon country, an atmosphere of anticipation arises in his writing: “Already we can think of nothing but the Habé whom we will soon see” (131). A few short days later, he is ardent. In a letter to his wife Zette he writes, “I continue to devote myself fully to my work and have even given myself over to it with real passion . . . What gives me moral comfort, and confirms my conviction of the necessity of this voyage, is that it is truly impossible to meet people this outlandish in the metropole” (134).

And then, suddenly, he is jaded: “It seems we are making little headway and the people, though they give up a few little secrets, carefully hide the essentials.” This cycle repeats throughout the text—passion, even obsession, followed by a kind of irritated despair at his research subjects’ unwillingness or inability to give him access to their lives and secrets. Sometimes this despair opens into a critique of the mission itself,

Of course, the project of the mission—to collect and document—and that of Leiris’s journal were quite different. As Brent Edwards writes in the introduction to his English translation, Phantom Africa is not itself an ethnography, and indeed, Leiris offers little that could be considered properly ethnographic. But if the “findings” of the mission’s work are not presented here, the structures that supported that work are: Phantom Africa offers a remarkably clear account of both the material and the affective infrastructures underpinning ethnographic work in the 1930s. On the one hand, through the details of everyday life, Leiris allows us to see the money, the transport, the tents, and the entire administrative apparatus of officials, communications, and social life that made the mission possible. And on the other, through his accounts of his own changing emotional state and glimpses into that of his companions, he allows us to see what Edwards calls the mission’s “common sense” (19) as well as its cravings and compulsions, in a way rarely so freely admitted. It becomes evident that the Mission Dakar-Djibouti was built on both a politically-driven and a felt attraction to difference. This is useful not merely as a document of a discipline in formation, but also as an example of the kind of information one might want in order to think carefully about the co-constitution of institutional forces and seemingly individualized desires.

In her (2007; 2014) work on ethnographic refusal, Audra Simpson describes the impulse to produce knowledge about difference as “anthropological need.” This need is tied to the requirements of governance (administrative regimes need to know in order to govern, and their “knowledge” is organized around units of otherness) but is also driven by the fact that “those in the metropole” needed to “know themselves in a manner that accorded to the global processes underway” (2007:67). Thus anthropological need had to do with more than the administrative efforts of the colonial regime. It had to do with an entire affective structure surrounding the production of knowledge about difference that was embedded in museums, in academia, in literature, and in the arts, and which tied the colonies to the metropole through the gathering and circulation of information (see also Conklin 2013).

Ethnographic refusal is then a conscious strategy to make certain kinds of knowledge inaccessible, in the context of histories in which the knowledge of and the governing of difference are difficult to untangle. As Simpson writes, for the anthropologist to acknowledge and participate in a refusal to give information is to recognize the implications of knowing. Simpson’s work comes after a period of self-critique that anthropology had simply not undergone by the time of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti (in France at this time, anthropology was only just beginning to consolidate itself as a discipline). It is interesting nevertheless to consider the question of refusal, because Leiris himself writes about it so frequently, and because it tells us something about the nature of his ethnographic desire.

Leiris regularly encounters refusals but only on a few occasions does he recognize them as such. Such moments clarify both the form and the limits of his ability to see the project in which he is involved. Take this example from the entry of August 26, 1931:

The old woman barely speaks. She smiles maliciously, parries all my questions, and transforms everything into utterly harmless facts. . . . I discover over the course of the afternoon that the reason she is unwilling to say more is that the woman who preceded her as head of the sect was arrested fifteen years ago by the French authorities, beaten, imprisoned, and exiled in Kati where she died in horrible misery. . . . When I learn the reasons for the woman’s muteness, I am . . . incensed with the administration, that iniquitous organization that allows such things to happen under the pretext of morality.” (144)

Despite what he was later to learn, Leiris’s language describing the encounter—“smiles maliciously,” “parries,” “utterly harmless facts”—lets the reader know that during the interview he was angry at this woman’s refusal. Only further down the page do we learn that his anger was soon after transferred away from the woman and toward the colonial administration. In keeping with the immediacy that Leiris cultivates throughout the book, the reader follows the author’s change in mental state as though tracking the events as they unfolded. This strategy is intriguing as an example of Leiris’s confessional style; Leiris does not hide his own initial annoyance, even as he later sees the refusal to have been justified. He appears to be revealing the injustice of his own irritation—but the immediacy-effect also leaves intact the palpable sense of frustrated desire. And despite his “incensed” response to a colonial abuse of power, Leiris does not seem to perceive his own wish to acquire information as a product of the same context. The relationship between knowledge and power (indeed, oppression) that his interviewee can see so clearly remains somehow unseen or at least unspoken by Leiris himself. So he acknowledges the logic of the woman’s refusal, but as an exception.

I’ve called Leiris’s interest in the other “ethnographic desire” because of the explicit parallels he draws between romantic obsession and the craving for information, but also because the idea of desire—as opposed to that of, say, the “gaze”—helps one better understand how anthropological need is deployed through the bodies and minds of ethnographers. The “detached gaze” that was cultivated and produced by scientific writing is also anchored in the work of individual researchers, whose desires have to be interpellated into the project. More, the very structure of desire seems well suited to describe some of the particular problems of self and otherness that lie at the heart of the ethnographic question. Desire, argues Judith Butler, is a pull toward the other through which one dialectically defines oneself. Appearing to arise from an interiority and yet shaped from without, desire is also at the heart of the paradox of the subject—because to be “a subject” is at once the precondition for agency and a form of subordination. Indeed, it is precisely by creating the interior space of subjectivity and shaping its desire that power operates on the subject (Butler 1997).

This is a long way of saying that I do not view Leiris’s explicit deployment of subjectivity as a writing technique to be separate from his passionate desire to gather information about the people he was encountering. Even the confessional mode itself, which he deploys frequently, is deeply involved in the issue of wanting to know. To think about this, I refer to Susan Sontag’s 1963 discussion of a different French ethnographer, Claude Lévi-Strauss. Sontag describes here a familiar contrast between the literary and the scientific. For Sontag, Lévi-Strauss’s vision of anthropology appears “literary” in its ambitions. Lévi-Strauss understood the anthropologist’s calling, Sontag writes, as a “systematic déracinement,” a self-alienation through the encounter with the other. Yet its methods (namely, structuralism) are dry and cold and “scientific.” In its effort at creating a totalizing structure, it seeks to “vanquish” its subject, to reduce otherness to “purely formal code” (1996: 77). Sontag points out that while these two tendencies seem to be at odds they are in fact linked, because the anthropologist is in control of, and even consciously exploiting, intellectual alienation. Thus, she writes, anthropology is characteristic of a modern sensibility, one which “moves between two seemingly contradictory but ultimately related impulses: surrender to the exotic, the strange, the other; and the domestication of the exotic, chiefly through science.”

Lévi-Strauss begins to be an influential scholar about a decade after the Mission Dakar-Djibouti, and he is the most important French figure in the consolidation of anthropology as a discipline with a canon, a method, and a theory. His brand of anthropology is therefore different from the more fragmented approach of Griaule and co., who represent anthropology before structuralism became the triumphant framework that it was to become. But Sontag’s description of structuralist logic helps to articulate how one might be misled by the question of the literary versus the scientific, or of the subjective versus the objective. Leiris mobilizes the confessional mode to argue that the work makes no claims to total representation, that it is literary/essayistic rather than “scientific,” and that its gaze is turned inward. This is complicated, however, because the shaping of Leiris’s desire reveals that subjectivity itself is what draws him so powerfully into the mission, indeed into the entire complex of “anthropological need” in the interwar period. At least in the context of French intellectuals’ engagement with the colonies in the interwar period, we can see that both the poetic and the scientific are modes for elaborating this dialectical movement around the question of otherness.

Phantom Africa has had a far greater impact as an example of literature than as a work of anthropology, and within anglophone anthropology it is virtually unknown. The book’s bordered circulation both speaks to the deep cleft between francophone and anglophone anthropology and reveals French anthropology’s much closer relationship with the arts, both literary and visual.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Conklin, Alice L. 2013. In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France 1850–1950. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2007. “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures 14: 67–80.

———. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sontag, Susan. 1996. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Dell.

For instance, this quote, which Edwards discusses in his introduction: “All this constant buying leaves me perplexed, because I have the strong impression we are going in a vicious circle: we pillage the Negroes under the pretext of teaching people to understand and appreciate them—that is, ultimately in order to mold other ethnographers who will go in turn to ‘appreciate’ and to pillage them.”↩

An example: “Livid with rage at a man who shows up to sell grigris and who, when I ask him for the magical formulas that must be recited when using them, gives a different version every time I make him repeat one of them so that I can write it down, and, every time that one is to be translated, gives even more new versions” (170).↩

The question of refusal and Leiris’s inability to accept it beyond the individual exception is useful for prodding a disciplinary conversation within anthropology around the complicity of anthropology and colonial power. The relationship between anthropological knowledge and power cannot be reduced to the question of whether ethnographers were complicit with or critical of the colonial regime. Whether or not members of the mission were critical of the colonial administration, the expedition’s rapacious desire for collecting is part of the same complex that also undergirded colonial governance (Bennet 2017). (And in fact, examples sprinkled through Phantom Africa reveal moments when the colonial administration actually protected communities from the expedition’s insatiable appetite for objects, again complicating the question.)↩

This is in part related to a distinction that Alice Conklin describes in the institutional formation of francophone vs anglophone strands. French anthropology was institutionally organized around the museum, where the British and US traditions were consolidated around the university.↩

4.8.19 |

Response

Refractions

I was wary of Phantom Africa when I first learned of it. The title alone (and, in all transparency, its juxtaposition with the author’s French name) suggested trafficking in the tropes of a dark, exotic, unknowable Africa. Brent Hayes Edwards’s introduction in this new, translated edition of the book went a long way towards allaying my concerns. In an extensive and deeply thoughtful discussion of how Michel Leiris’s text has been taken up by commentators (including Leiris himself) across the fields of history, literature, anthropology, in the United States and in France, from its first publication to the time of this translation, Hayes Edwards establishes that the complexity, multiplicity, and ambiguity of Phantom Africa form the basis for the book’s enduring relevance and value. He convinced me that the book was worthy of serious engagement, rather than the dismissal towards which I had initially been inclined.

Phantom Africa interpellates so many parts of my being—as a black woman, as a West African, as the child of people who grew up as subjects of the French Empire, as someone obsessed with understanding my inner worlds; and of my experience—as a recently minted anthropologist, moreover, one who works on the idea of Africa and whose first fieldwork experience is still quite fresh. It isn’t difficult to see how this book, a compendium of hundreds of entries often blurring the lines between field notes and journal entries that chronicle a white French man’s journey on an ethnographic expedition through West and East Africa to collect art and artifacts—sometimes by force—at the height of European colonialism on the continent would trigger a great deal of aversion within me. But it also sparked resonance. The dozen or so drafts of this essay on my computer attest to how difficult I have found it to reconcile these two reactions.

On one hand, I found Phantom Africa violent. At the most fundamental level, in the very premise of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti it documents, in the assumption that the members of the expedition had the right to access people, spaces, objects, and knowledge in the various locales they visited. The mission, and other ethnographic voyages like it, were premised on the conviction that collecting and documenting artifacts from colonies, by whatever means necessary, would ultimately benefit the populations from which these objects were taken. Indeed, one of Leiris’s stated motivations for taking part in the mission was the possibility it presented for helping to “dissipate” and “undermine” racial prejudice (Leiris 1930, quoted on p. 5). And yet, as Edwards notes, “there can be no doubt that [the expedition] was undertaken explicitly in the service of the French colonial empire” (3).

One of the most egregious examples of this violence and the ways it intersected with colonial regimes of oppression is the case of the mission’s acquisition of a kono, a sacred ritual object, in Bla, a village along the mission’s itinerary in Niger in 1931. When despite their initial approval, villagers ultimately refuse, through a variety of stalling techniques, to turn over the kono to the anthropologists, Marcel Griaule, eminent anthropologist and expedition leader, threatens to have the police take them before the colonial authorities. Once the village chief’s “permission” is thus secured, Griaule and Leiris enter the hut and remove the kono, “creeping out like thieves while the devastated chief flees” (154).

The text’s violence also manifested in Leiris’s observations, in the banal ways that an otherwise sensitive description slipped into painful tropes. Here, the trope of the African-as-child:

A great religious emotion: this dirty, simple, elementary object whose abject quality is a terrible force because it holds in concentrated form what these men consider to be absolute, and because they have stamped it with their own force, like the little ball of earth a child rolls between his fingers when playing with mud. (147)

Here, that of the African-as-animal lookalike:

Baba Keyta takes me to an old sorceress, literally as pretty as a monkey . . . We find her with a group of other women . . . One is lying on a mat and looks quite nasty; the other is lolling on her mother’s bed, next to her, and either watches me or gazes off into space, as beautiful, literally, as a beautiful cow (it is no laughing matter). There is also a young Toucouleur girl who comes and goes from time to time and who also sits on the bed, as pretty as a common gazelle, literally, and again it is no laughing matter.

1 (143–44)

Or again in the expression, however self-reflexive, of his power and status as a white, French man: “I realize in a dazed stupor, which only later transforms into disgust, that you feel pretty sure of yourself when you’re a white man with a knife in your hand” (156), Leiris writes about his part in the theft of the kono.

Leiris became increasingly aware, as the mission progressed, and certainly by its end, that he had been not only implicated, but complicit, in the very structures of oppression that he had believed himself to be challenging through his ethnographic work. In the foreword to the 1934 edition of Phantom Africa, he observes that his journal reveals him to be, among other things, “biased—even unjust—inhuman (or ‘human, all too human’), an ingrate, a false brother, who knows?” And in the foreword to the 1951 edition, he describes the publication of his journal entries even though do not reflect his current perspectives as “a sort of confession.” But Leiris himself seems to recognize that there are limits of the redemptive powers of contrition:

If I put forward in my defense, as I did sixteen years ago, the precedent of Rousseau and his Confessions, it is with far less assurance, for I am now persuaded that no man living in this iniquitous yet indisputably modifiable—in at least a few of its most monstrous aspects—world we live in should be able to get in the clear by means of a flight and a confession. (65)

I am inclined to agree.

***

And still, as I read through it, Phantom Africa brought about (to my dismay!) moments of intense recognition and resonance. These moments centered on the text as a record of a first-time ethnographer’s experience—still fresh in my memory, being just a few years removed: the overwhelm; the beginner’s faith in the promise of ethnographic research as a mode of and means to definitive knowing; and—not unrelatedly—the sometimes unacknowledged personal agendas that can graft themselves onto this initial (and initiatory) experience.

For Leiris, part of the appeal of the mission was the methodical, scientific nature of ethnographic research, and its promise of rigor; rigor that could produce facts, and facts which could in turn help fight prejudice against blacks and Africans. But there was also the lure of dépaysement, that untranslatable French term for being out of one’s familiar context, losing one’s bearings, on which so much of the learning that happens in fieldwork is taken to depend. And its promise of greater clarity, both outwardly—onto the research subject, and inwardly—as if we are able to access a core, elemental version of ourselves once what is familiar is shaken off. The deep dive of fieldwork presented Leiris with the possibility of leaving parts of his self behind, the hope that “this long voyage in remote lands—and true contact, via scientific observation, with their inhabitants—would transform him into a different, more open man, cured of his obsessions,” as Leiris noted himself (59). Further, as Edwards points out, by undertaking this voyage in Africa specifically, Leiris also sought to satisfy his own fantasies of “the dark continent.”

Leiris was clear on his personal agenda for the voyage; it was a quest to forget. In my case, however, it was only a couple of years after completing my dissertation fieldwork—for which I had returned to Togo, my home country, to conduct ethnographic research after a twenty-plus-year absence—that I realized that subtending my research’s interrogation of the aesthetic and material renegotiation of Dutch Wax cloth designs’ “African-ness” as its manufacturer remade itself into a global brand was a personal interrogation of my relationship to Togo, of the extent to which it was still, could still be “home.” In Togo, Dutch Wax cloth designs are memory objects par excellence, commonly referred to as “our grandmothers’ cloth.” During a follow-up fieldwork trip to Togo after graduating, I wrote to my dissertation advisor:

I’ve been in Lomé for the past month. It’s been good work-wise, with lots of ideas and writing, and I’m finding being here much more manageable than I did during the dissertation research. I’ve been thinking a lot about how my research seems to be running parallel to some sort of quest to understand my own personal history better; that hadn’t been as apparent to me before as it has become during this trip.

And to a dear friend back in the United States:

[I’m realizing] that a big part of my wanting to come to Lomé is about not wanting to be afraid (anymore). As I think I mentioned, since my family left, Lomé has been shrouded in a lot of fear in my family. Mainly because of what the conditions were when we left, when the country was on the brink of a civil war, disappearances were happening left and right, bodies kept getting pulled out of the laguna by the dozens, there was a curfew, and incessant reports of arbitrary uses of violent, often lethal force. Clearly life has gone on, and things are nowhere near as tense as they were at that time, but the feeling of fear has remained, for me at least. And I think I’m tentatively trying to conquer it, to settle on a different story.

My personal agenda for this research, it turned out, was a quest to remember. And like Leiris’s, my personal agenda demanded, took over, space in my writing. I struggled with writer’s block when I was writing up my dissertation until I gave myself permission to incorporate more personal, memoir-type writing into the text.

Which leads me to my favorite part of Edwards’s new edition of Phantom Africa: the inspired decision to include excerpts from Leiris’s letters to his wife, Zette, back in Paris throughout the voyage. The juxtaposition of the missives with his journal entries made palpable (and immediate) Leiris’s vulnerability, his loneliness while in the field (“I no longer have the least affection for any of my companion and I feel so alone among them . . . The only thing that connects me to life is your letters,” he writes to Zette about five weeks into the mission [87]). The letters help to make him a more sympathetic character.

Anyone who has carried out fieldwork will attest to the crucial role that your community back home—friends, partners, graduate school cohort mates, dissertation committee members when you’re lucky (I was)—play in the fieldwork experience. They sustain you through the inevitable meltdowns, they give you a space to air out your frustrations, they anchor you. Further, the correspondence also allows you to process what you are seeing and experiencing in the field, to give voice to the emotional experience of it all. When I was leaving for dissertation fieldwork, my graduate school advisor encouraged me to keep track of the emails I sent to loved ones while in the field, and to return to them when the time for writing came; the casual and conversational nature of those exchanges can make for particularly insightful and sharp analysis. Indeed, in his letters to Zette, Leiris tended to take a more pronounced, reflexive distance from the project he was embarked on, and was most transparent about his own ambivalence about it all.

***

Despite these moments of recognition, I remain ambivalent towards Leiris and Phantom Africa. For if resonance there is between our experiences as first-time ethnographers, the points of disjuncture, centered on our respective situated positionalities as ethnographers in the field, our different historical contexts notwithstanding, are momentous. It might seem unreasonable to situate Leiris’s voyage in the 1930s and my own experience in the 2010s within the same time-space frame. But the account relayed to us in Phantom Africa are hardly ancient—or even distant—history. After all, a commission established at the sustained behest of African political and cultural actors is at this very moment examining the terms for returning objects taken during colonial era ethnographic expeditions like the Mission Dakar-Djibouti to their places of origin. The story is ongoing. Maybe the kono will find its way back.

Further, in a recent article in one of anthropology’s flagship journals, five black, brown, indigenous, and queer female anthropologists (Maya Berry, Claudia Chávez Argüelles, Shanya Cordis, Sarah Ihmoud, and Elizabeth Velásquez Estrada) poignantly relate the ways in which their gendered and racialized embodiment has punctuated their field research (Berry et al. 2017). Despite existing writing on the specific challenges that female anthropologists face in the field, Berry et al. tell us, “the notion of engaging in fieldwork is often approached by activist anthropologists [and, I would argue, in the field more broadly] in a gender-neutral way, one that still assumes an unencumbered male subject with racial privilege, to whom the field means a space far from home that can be easily entered and exited” (539). Through accounts of harrowing situations they each found themselves in, the authors cast a light on the ways that inhabiting their black/brown/indigenous and female bodies rendered them vulnerable to the very power dynamics, the very violence, that their research as activist anthropologists sought to engage. Taking the field experiences of anthropologists who are not white men seriously, they contend, requires rethinking the premises of fieldwork and of its place in anthropological praxis. Here too, then, the story—and the work—is ongoing.

It might seem unfair to read Phantom Africa through the lens of the present, but the enduring relevance of place, history, race, and gender in anthropology today—from the ethnographer’s positionality in the field to the projects of knowledge production that ethnographic research is and has been complicit in—make it almost impossible not to.

Works Cited

Berry, Maya J., et al. “Toward a Fugitive Anthropology: Gender, Race, and Violence in the Field.” Cultural Anthropology 32.4 (2017) 537–65.

Leiris, Michel. Phantom Africa. 1931. Translated by Brent Hayes Edwards. New York: Seagull, 2016.

Admittedly, Leiris is an expert and somewhat equal opportunity shade thrower, with plenty to spare for the Europeans with whom he interacts.↩

4.15.19 |

Response

The Black Translator

in Pursuit of Phantoms

Recently I taught Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the classic 1941 collaborative experiment in documentary by writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans. In the midst of their unsparing and impassioned portraits of three white tenant farmer and sharecropper families in rural Alabama in the 1930s, there is a short chapter titled “Near a Church.” Agee and Evans had come upon a modest, rough-hewn, but breathtakingly beautiful country church and, in awe at “the subtle almost strangling strong asymmetries of that which has been hand wrought toward symmetry,” they decide to photograph it.

Wanting to take shots of the interior as well as the exterior, they briefly consider forcing the locked door, but hesitate when they notice a young black couple coming toward them up the road. The man and woman glance at Agee and Evans, “without appearing to look either longer or less long, or with more or less interest, than a white man might care for,” and take in the scene of the two strangers lurking by the house of worship with their tripod and camera. Unceremonious greetings are exchanged, and the couple continues on their way. Without the slightest accusation, Agee writes, the couple “made us, in spite of our knowledge of our own meanings, ashamed and insecure in our wish to break into and possess their church, and after a minute or two I decided to go after them and speak to them, and ask them if they knew where we might find a minister or some other person who might let us in, if it would be all right” (36–37).

The couple had advanced about fifty yards down the road, and Agee hurries to catch up with them. The man and woman notice him following them: “they turned their heads (toward each other) and looked at me briefly and impersonally, like horses in a field, and faced front again; and this, I am almost certain, not through having heard sound of me, but through a subtler sense” (37). He tries to wave at them but they turn away so quickly they do not notice. A few seconds later, impatient, and realizing that he is not advancing fast enough to overtake them, Agee breaks into a trot. He writes:

At the sound of the twist of my shoe in the gravel, the young woman’s whole body was jerked down tight as a fist into a crouch from which immediately the rear foot skidding in the loose stone so that she nearly fell, like a kicked cow scrambling out of a creek, eyes crazy, chin stretched tight, she sprang forward into the first motions of a running not human but that of a suddenly terrified wild animal. In this same instant the young man froze, the emblems of sense in his wild face wide open toward me, his right hand stiff toward the girl who, after a few strides, her consciousness overtaking her reflex, shambled to a stop and stood, not straight but sick, as if hung from a hook in the spine of the will not to fall for weakness, while he hurried to her and put his hand on her flowered shoulder and, inclining his head forward and sidewise as if listening, spoke with her, and they lifted, and watched me while, shaking my head, and raising my hand palm outward, I came up to them (not trotting) and stopped a yard short of where they, closely, not touching now, stood, and said, still shaking my head (No; no, oh, Jesus, no, no, no!) and looking into their eyes; at the man, who was not knowing what to do, and at the girl, whose eyes were lined with tears, and who was trying so hard to subdue the shaking in her breath, and whose heart I could feel, though not hear, blasting as if it were my whole body, and I trying in some fool way to keep it somehow relatively light, because I could not bear that they should receive from me any added reflection of the shattering of their grace and dignity, and of the nakedness and depth and meaning of their fear; and of my horror and pity and self-hatred. (37–38)

It is an indelible portrait of the visceral terror of what it meant to be African American in the US South in 1936, when the most innocuous interaction could suddenly turn life-threatening. Agee’s wrenching, drawn-out rehashing of his own guilt at finding himself implicated in such a dynamic (“The least I could have done was to throw myself flat on my face and embrace and kiss their feet,” he agonizes pathetically) only serves to underline the precariousness and horror of the racial regime: an ever-present, silent undercurrent of potential violence that could erupt into bloody view at the slightest provocation.

There is no question that, not unlike—although not identical to—the volatile racial climate in Alabama, colonized Africa in the 1930s was suffused with systemic terror to a degree that affected every register of human interaction, from the most official and “impersonal” protocols of governance, to the fundamental civil institutions of work, worship, and learning (as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o once put it, as a schoolboy in colonial Kenya even his relationship to the English language “was based on a coercive system of rewards and terror”),

In addition to documenting the terror of the colonial context in Africa of the 1930s, however, Phantom Africa teaches us something else, too. Even in a situation where terror is systemic and all-pervasive—a cauldron of subjection that operates below consciousness: a stirring in the bowels, a tension in the sinews—the most remarkable thing of all is that the affective palette available to the terrorized is not circumscribed by terror. It is not all panic, distraught bawling, and cowed genuflection.

We might describe this uncircumscribed affective palette as a product of an anoriginal dereliction, a fugitivity that exceeds and, more importantly, precedes and anticipates the modes of regulation that would constrain it. In Foucault’s famous formulation, “it is not that life has been totally integrated into techniques that govern and administer it; it constantly escapes them.”

What do we do with that unruly, unclassifiable range of response inventoried in Phantom Africa—that proliferation of unpredictable and sometimes enigmatic interactions where Africans refuse to be reduced to terror? The children on the beach at Ngor, sailing little toy pirogues and running after the ethnographers’ car yelling “Sunday! Sunday!” (83). Or the two smiling young women who come up to the vehicle as they depart and launch into “a few dance steps, clapping their hands,” leaving Leiris puzzled as to the “exact meaning of this display of coquetry” (86). Or the lamido of Ray Bouba, in northern Cameroon, who receives Griaule’s team with a ludicrously extravagant feast (277–79). Or the inhabitants of Kita (in present-day Mali), who tell the ethnographers that a nearby mountain is teeming with “dangerous and sinister devils,” possibly in order to keep them from stumbling across the many grottoes filled with graffiti of unexplained origin (126). Or the Shilluk men the team encounters at a Syrian trading post by the Nile in Sudan who, when the ethnographers try to photograph them, “move away or turn their faces with expressions like little girls simpering” (332). Or the “elegant” balambaras Gassasa, head of customs at the border in Gallabat, who receives the Mission Dakar-Djibouti wearing “a big revolver on his hip” (356) and obstructs their passage into Ethiopia with an endless stream of paperwork. Or the alternately imperious and ingratiating Malkam Ayyahou, “cackling with laughter” as she singes the hair off Leiris’s forearms and eyebrows with an exuberant explosion of gunpowder during a ceremony in Gondar (475). Or the “dandy” (267) Toucouleur interpreter in Poli (Cameroon), who regales Leiris with “comic imitations of a schoolmaster satirizing a dunce” (268). There are too many to catalogue: indeed, the texture of the book as a whole is this diverse litany of ambiguous human interaction.

In rereading Phantom Africa, I have come to realize that in my introduction I was too dismissive when I wrote that Leiris “has little to say” in the book “about the Africans who served as translators for the Mission” (44). On the contrary, some of the most nuanced portraits in Leiris’s journal are his discussions of the African interpreters who accompanied the Mission Dakar-Djibouti. They are not intimidated or subservient, but complexly human, sometimes mercurial or truculent, and often erudite. Leiris dwells for instance on the “warm and light-hearted” atmosphere in their compound one evening when their Senegalese interpreter and assistant Mamadou Vad, a former railroad mechanic who worked on the expedition for four months in the summer and fall of 1931, “rises with his freshly shaven head from the mat where he has been stretched out and scrupulously records some good story (in Wolof, transcribed not only into French but also into Arabic script) in the little notebook Griaule gave him” (138). Earlier that day, in the car, Mamadou Vad tells “dazzling” and humorous anecdotes: “In Kayes, going to fetch some milk, he surprised a man copulating with his cow; ever since, when he runs into him he asks: ‘How’s your wife?’” (137). Even in this minor example over the course of a single day, what is notable is the complex dynamic between “work” and “play”; if some of the stories Vad records and translates for the team might fall under the instrumental task of collecting information for ethnographic purposes, some clearly do not.

There is obvious affection in the way Leiris habitually describes the interpreters and informants working with the Misson Dakar-Djibouti, men such as Mamadou Vad, Dousso Wologuem, Ambara Dolo, and Ambibe Babadyi. At times they are resourceful, at times they are disinterested, and at times they are capricious or recalcitrant. In November 1931, on a day trip to Yougo, Leiris records that one of their principal Dogon contacts, Ambara Dolo, “who is sporting his ever-present earrings, forage cap, black frock coat with green buttons in the back, breeches, and umbrella, refuses to carry anything but our storm lantern and the big bundle of personal effects he is wearing slung over his shoulder bandolier-style, like a peasant returning from the fair in Fouilly-les-Oies” (207).

When another interpreter, the idiosyncratic former telegraph operator Baba Keyta, a “bearded giant with completely albino legs and forearms” (131), joins the team in Mali, Leiris is enthralled by his charismatic personality and his “sumptuously garbed” appearance (133). One day Baba Keyta turns up wearing “white sandals, an impeccable white suit with a high collar, officer-style, a colonial helmet a bit too large for him—which he adjusts using strips of paper torn from an old issue of La Dépêche Coloniale—and, to complete the image, a narrow-waisted European winter overcoat and a freshly shaven head” (134). Leiris tells his wife that he finds Baba Keyta “comical,” but “deeply moving,” too, because (as Leiris puts it) Keyta possesses “true candor, true fantasy” (135). There is certainly obfuscation in Leiris’s invocation of “true fantasy” here—just as in his effusive descriptions of Africa as an “ocean of poetry” (as I discussed in my response to Kaiama Glover)—and yet there is a quality in the detail of the description of Baba Keyta that goes beyond the instrumentalism of stereotype.

It may be worth reflecting on the fact that so many of the enigmatic interactions in Phantom Africa involve the African translators on the Mission Dakar-Djibouti. As both Kaiama Glover and Amiel Bize discuss in some detail, Leiris and his fellow ethnographers encounter a good deal of hedging, prevarication, and misdirection on the part of the Africans from whom they attempt to extract information. Leiris remarks at one point that “the natives often pass off as casual amusement something whose religious purpose they wish to conceal” (123). Bize comments, “Leiris regularly encounters refusals but only on a few occasions does he recognize them as such. Such moments clarify both the form and the limits of his ability to see the project in which he is involved.” Even if Leiris remains oblivious to their full implications, these moments in Phantom Africa are traces of overt resistance, where the only available strategy for a “native informant” conscripted into the information-gathering drive of colonial anthropology is silence and opacity. But there is something else going on when the resistance is coming not from the “native informant” but instead from the translator—that is, emanating from the very factotum who is meant to ensure the linguistic transparency of the “native” to the anthropological understanding. As I mentioned in my response to Glover, Leiris is particularly annoyed when faced with this impedance (a resistance within the mechanism of mediation). Given how often it happens in Phantom Africa, we might even need to consider the way the book stages the specific opacity of the translator.

There are even corollaries to this question, such as the intriguing fact that a number of these assistants and translators are so young. Leaving the Dogon region in November 1931, the team says farewell to their “best friend among the children,” the eleven-year-old Abara. Marcel Griaule gives him a watch as a present, but the boy is not satisfied: “I want to go with you, monsieur . . .” It is “impossible to take him,” Leiris comments; “he is too weak and small, but we’ll be back again. If he learns French well, he’ll be our head interpreter.”

Or one might point to another of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti’s young assistants, the thirteen-year-old Mamadou Keyta, who joins the team in Bamako in August 1931 as an interpreter, against the wishes of his father (144–45). Impressed by his language skills and his enthusiasm, Griaule tells the boy that he wants to make “a great ethnographer out of him” (!), and they start actively training him and letting him participate in the fieldwork (157). Mamadou Keyta travels with the team for six months, but Griaule eventually concludes that he does not have the necessary aptitude for the profession and sends him back home in February 1932. Keyta is “crushed” by the news that he is being dismissed, Leiris writes, and the boy leaves devastated.

To return to the issues raised in Amiel Bize’s response, here is yet another sort of ethnographic desire. If one wanted to think about the complex and unarguably pivotal role of the African interpreter in the history of French colonization, in other words, Phantom Africa would not be a bad place to start. In fact, the first chapter of Justin Izzo’s forthcoming book is an eye-opening comparison of Leiris’s travel diary with the extraordinary work of Amadou Hampaté Bâ, the towering Malian writer and ethnologist whose writings are in part a profound reflection on his own training in the field during the colonial era.

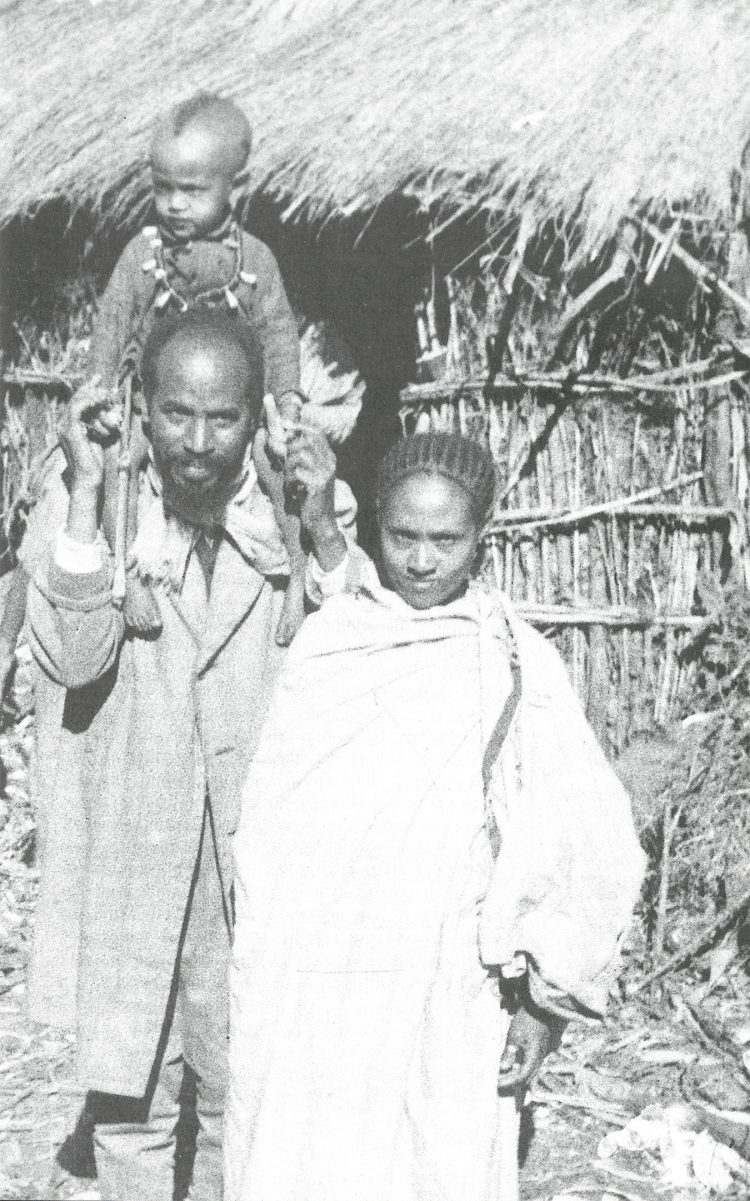

The historical character in Phantom Africa who has stuck with me the most is one mentioned by none of the respondents in this dossier: Leiris’s most important African collaborator during the Ethiopian portion of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti, the Eritrean diplomat, former priest, librarian, teacher, and linguist Abba Jerome. Two decades older than Leiris, Abba Jerome was a highly accomplished yet self-effacing intellectual whose career has been lamentably eclipsed because he published very little during his lifetime. He played a crucial role as a representative of Haile Selassie after World War I during multiple diplomatic missions to Europe, helping especially to negotiate the conditions under which Ethiopia would be admitted to the League of Nations in 1923. After the end of the Italian occupation, he was appointed conservator of manuscripts of the National Library of Ethiopia, where he served until his retirement in 1964, when he was asked to join the faculty of the Ecole Nationale des Langues Orientales in Paris, where he taught Amharic until 1977. (Amazingly, Leiris and Abba Jerome renewed their acquaintance when the latter moved to France, and even returned to their collaboration on some of the research they had pursued together on the zar in Gondar more than three decades earlier.) Abba Jerome died in Cannes in 1983, at the age of 102.

There is not space here to reflect in depth on their collaboration, or to provide a full portrait of Abba Jerome himself. I will only include a few words from Leiris’s tribute to his old colleague, written for a Festschrift edited by the scholar Joseph Tubiana just before Abba Jerome’s death.

Reflecting on Abba Jerome, Leiris writes:

A figure too protean for it to be possible to sketch his silhouette for once and for all, this tightrope walker without a wire or a balancing pole—whose dress, free of any exoticism of country or era but slightly haphazard, was that of a European of the period—seemed to take pleasure as much in adopting (with the aid of his black beard and sparkling eyes) the expressions of a comic opera Mephistopheles, as in taking on the mysteriously grave allure (while he confided some piece of learning, whispering in your ear) of some hermetic philosopher.

12

In one of the entries in Phantom Africa, Leiris remembers, he had described Abba Jerome as “a man with a poetic instinct for information, which is to say, a feeling for the apparently insignificant detail that puts everything in context and gives a document its stamp of truth” (466). Looking back fifty years later, Leiris muses that “the praise I gave him then strikes me now as all too timid: it still considered him from the angle of ethnographic practice rather than that of poetry.” Abba Jerome was a man with a deep “literary” sensibility, Leiris concludes, in a way that went deeper, and beyond, the practicalities of his collaboration in the research:

Beyond the tasks imposed on him by his official role as my translator and scribe, he seemed to find a keen satisfaction in pinning on paper (without thereby transforming them into dead butterflies) the words worthy of attention that we heard in the course of a discussion or that he simply caught out of the air during a ceremony or interview session with one of the possessed among whom we were working . . . I remain profoundly attached to Abba Jerome, a man whose character borders on the phantasmagorical, and who allowed me to discover the mythical world of the zar in a more vibrant way than I could have dreamed.

13

Although I am not an anthropologist by training, I recognize in my own relationship to Phantom Africa as a translator the strange and at times troubling dialectic of repulsion that Edoh describes. Having spent so much time with the book, I’ve thought a great deal about what it means for an African American translator to render this particular volume into English. As a scholar whose work focuses especially on the emergence of black radical thought in circuits of exchange and translation among African diasporic intellectuals and artists in the Americas, in Europe, and in Africa, I’ve also pondered the significance of translating a renegade classic that is the inimitable product of the fraught interface between European anthropology and colonialism.

In 2016, the writer and translator John Keene published a much-discussed manifesto on Poetry Foundation blog Harriet titled “Translating Poetry, Translating Blackness,” in which he makes a forceful argument that “we need more translation of literary works by non-Anglophone black diasporic authors into English, particularly by U.S.-based translators.”

But I feel strongly that we need to be able to stake a claim to the core of the Western literary tradition as well, especially when it is a matter of monumental works by white writers grappling so directly with the place of Africa and Africans in the world. Given the triangulation that brought Leiris from a dilettante’s fascination with African American jazz in Paris of the 1920s to the Mission Dakar-Djibouti and the African continent,

Although none of my generous interlocutors for this dossier have mentioned it, the element of Phantom Africa where I feel that this self-consciousness about my role as a translator had a palpable impact on the form of the English version is something I discuss in the section of my introduction called “Traces of Translation” (43–50). Translating the book, I sensed a resonance between my labor and that of the African interpreters who played such a key part in the entire Mission Dakar-Djibouti. Their scrupulous mediation preceded mine and, in a sense, formed the foundation of the entire enterprise. I was determined throughout to listen for their presence as they patiently ferried language not their own. When I realized that Leiris—in his obsession with immediacy—repeatedly elides the presence of the African interpreters around him with a sly grammatical contortion (using passive formulations such as lui font dire or “have it said to him,” without specifying who is doing the telling) (46), I decided both to describe the effect in my introduction and to keep, wherever I could, the translators in view in the English version, adding brief contextual phrases (e.g., “I have it said through the interpreter…”) (247) to highlight the agency of linguistic mediation. It’s a small thing, admittedly—another pursuit of phantoms. But it was my quiet way of doing justice to the legacy of black translators: my way of keeping Dousso Wologuem and Abba Jerome from slipping out of sight.

Abba Jerome, Emawayish, and her son Guietatcho in the camp of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti on the grounds of the Italian consulate, Gondar, Ethiopia, August 1932.

James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941; reprint Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001), 36. Subsequent page references will be given parenthetically in the text.↩

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, “Translated by the Author: My Life in between Languages,” Translation Studies 2.1 (2009) 18.↩

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26 (2008) 4.↩

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1978), 143. It should be evident that I am alluding here to the argument that Fred Moten has been developing for some time now that “blackness is ontologically prior to the logistic and regulative power that is supposed to have brought it into existence.” See Moten, “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh),” South Atlantic Quarterly 112.4 (2013) 739. One of the places where Moten discusses the Foucault quotation is Moten, “Knowledge of Freedom,” CR: The New Centennial Review 4.2 (2004) 273–74.↩

A wealth of biographical information about Mamadou Vad and the other interpreters and assistants employed by the Mission Dakar-Djibouti has been gathered by Eric Jolly (the historian and director of the Institut des mondes africaines) for A la Naissance de l’ethnologie française: Les missions ethnographiques en Afrique subsaharienne (1928–1939) (2017), a useful website devoted to the history of French anthropology in the first half of the twentieth century. The page regarding Mamadou Vad is available online at http://naissanceethnologie.fr/exhibits/show/mamadou_vad.↩

In fact, Abara Dolo did end up working as an interpreter for the subsequent French ethnographic missions in the region in 1935 and 1937. See http://naissanceethnologie.fr/exhibits/show/abara_dolo.↩

Justin Izzo, “Ethnographic Didacticism and Africanist Melancholy: Leiris, Hampaté Ba, and the Epistemology of Style,” chapter 1 in Experiments with Empire: (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming 2019). For an introduction to Amadou Hampaté Bâ’s brilliant work on the role of African interpreters under French colonialism, one might start with the second volume of his memoirs, Oui, mon commandant! Mémoires II (Arles: Actes Sud, 1994), as well as his masterful portrait L’étrange destin de Wangrin; ou, Les roueries d’un interprète africain (Paris: Éditions 10/18, 1998), the latter of which is available in English: The Fortunes of Wangrin, trans. Aina Pavolini (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2000).↩

For an overview of Abba Jerome’s life and career, see Jacques Mercier, introduction to “Encens pour Berhané,” in Michel Leiris, Miroir de l’Afrique, ed. Jean Jamin (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 1065–66. I also discuss his collaboration with Leiris in researching the zar in my introduction to Phantom Africa (39–41).↩

Michel Leiris, “Encens pour Berhâné,” in Guirlande pour Abba Jérôme: Travaux offerts à Abba Jérôme Gabra Musé par ses élèves et ses amis, ed. Joseph Tubiana (Paris: Le Mois en Afrique, 1983), 1–5. This essay is also collected in Miroir de l’Afrique, 1067–71, although I will quote from the original publication (due to slight discrepancies in the latter version).↩

Leiris, “Encens pour Berhâné,” 1.↩