Infamous Bodies

By

1.10.22 |

Symposium Introduction

Samantha Pinto’s Infamous Bodies has changed conversations in the field of Black feminist studies, insisting not only on the importance of celebrity as an analytic, but also centering difficult and challenging objects as necessary for the continued vibrancy of our field. Pinto’s book centers the category of celebrity as a way in which Black women come into visibility, and as bodies (famous and infamous) who come to hold cultural and political desires, attachments, and longings. Pinto treats celebrity as a “genre of black political history, one that foregrounds culture, femininity, and media consumption as not merely reflective of, ancillary to, or compensation for black exclusion from formal politics, but as the grounds of the political itself” (3). What do we want from Black women celebrities, Pinto asks, not only in the moment of their fame/infamy, but in the decades and centuries to follow, when their stories are obsessively told and retold? In probing these longings, Pinto pushes her readers—and the fields of Black studies and gender studies—from what she terms the “attendant genres of heroism and tragedy as the model of black political subjectivity” (10) toward a delightfully uncomfortable embrace of uncertainty and vulnerability. She turns attention to Phillis Wheatley, Sarah Baartman, Sally Hemmings, Mary Seacole, and Sara Forbes Bonetta, all of whom have proven to be “difficult” in their complexity, and in their challenges to categories of freedom, consent, contract, and citizenship. In so doing, she suggests the importance of difficult and uncomfortable figures for Black feminist scholarship, as it is these figures that can challenge and unsettle entrenched conceptions of race, rights, and representation. Pinto’s book is breathtaking in its intellectual reach, speaking across multiple fields, including Black feminist theory, literary studies, performance studies, and ongoing debates about rights (and the afterlives of rights) in critical legal studies. The responses to Pinto’s book—from scholars working across fields—are truly a testament to the interdisciplinary reach and provocativeness of Infamous Bodies, a book which has already prompted necessary conversations.

1.17.22 |

Response

Response to Infamous Bodies

Liberal humanist versions of black feminism depend on strategies of legibility and legitimation. These versions rely on the need for individuals to be recognized by and within dominant power structures as rights-bearing, sovereign subjects. Consent, agency, and autonomy are assumed to be the fundaments of freedom. This leads to particular tactics, such as the historical recovery projects that rewrite the complicated lives of black women, representing them instead as triumphalist stories of overcoming adversity, of individual strength and genius. The status of recognition by the dominant body politic takes the place of what could be fundamental alterations to the fabric of historical memory.

I join Pinto in countering the liberal humanist politics of “corrective” narratives. I share a critique of notions of legibility and the narrative obscuration it demands. Such tactics dull the otherwise thorny ambiguities of these women’s lives, where consent, agency, and autonomy are not as clear cut as such liberal humanist narratives would have them. In Black Utopias I argue that Sojourner Truth, as part of a culture of black women preachers in the 1830s and 1840s, must be understood in more complicated terms than liberal black studies and feminisms would proffer—particularly when considering her bonded relationship to her owner and other dominating men, her relationship to her children, and her rejection of a heteronormative domestic life.

In challenging the liberal humanist model of the rights-bearing individual, Pinto posits instead the “vulnerable subject,” in order to displace the ideal of the self-volitional individual as the necessary model citizen for whom the social contract is conceived. This positionality also unseats the ways in which certain black feminisms situate injury and trauma as the common bonds around which to organize. A type of personal agency exists, but through sociopolitical, cultural, and economic contingencies. Pinto picks wonderfully complex figures with which to explore the mechanics of corrective representational strategy at its fracture points. Each of the individual women who organize her chapters—Phyliss Wheatley, Sally Hemings, Mary Seacole (dreadfully underacknowledged) Saartjie Bartman, and Sarah Forbes Bonetta—enjoyed a notoriety in their own time, and there are multifaceted meanings to their fame. I would emphasize, and perhaps explore further, that their forms of celebrity continue to accrue meaning in subsequent eras, and have meanings specific within particular sociohistorical conjunctures. The meanings of their fame rearticulate over time, and I would argue that fame itself means something different now than it did in past eras.

Each of these women’s lives demonstrate the limits of the concepts of inclusion, consent, rights discourse, and the social contract. Considering the particular kind of fame drawn around Phyllis Wheatley is an opportunity to think about the politics of representation and the myth of inclusion. Wheatley was famous for not just her genius, her gift, but also, and perhaps penultimately, for her educability. Wheatley was used to represent if not the negro race, then to demonstrate and prove the race’s educability, a major point of debate within arguments for and against slavery. Contrary to the ideal subject of a capitalist liberal humanism, Wheatley was considered a skilled poet not of her own initiative or wherewithal, but through grooming and training. With the right guidance, then, negros could at least mimic their masters. Pinto’s readings of Saartjie Baartman and Sally Hemings offer rich and textured analyses of the limits of consent as a category for black women. In both cases Pinto challenges notions of romantic love as somehow a deciding factor in whether or not the women consented. Indeed, consent is not a useful category for women for whom consent was not applicable.

I can follow Pinto in her choice of subjects, and her critique of corrective history. But the fundament of Pinto’s project is shaped by a tendency in US cultural studies that strips it of its class analysis, and I find this troubling. Throughout the book Pinto uses the familiar language of cultural studies:

This project insists on the significance of cultural production and reception . . . as a mode that labors alongside law and civic participation in the public sphere to make the “drama” that constitutes and reconstitutes the afterlives of rights.

This description could apply to the many studies influenced by British Cultural Studies scholars, particularly Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall, with his students at the Birmingham Center, as well as the work on culture by US labor historian Robin Kelley. British cultural studies, and to an extent its US variant, challenged a Marxist economic fundamentalism, arguing that we consider culture as critical site of contestation. But as with most US cultural studies, Pinto attempts to deracinate cultural studies from its essential materialism. She continues:

This “drama” displaces a primary critique that locates celebrity culture squarely within the realm of Marxist theory. Infamous Bodies critically and curiously explores what capitalism’s seeming products—celebrity and commodity culture—afforded through and opened up for black women’s embodiment.

In arguing for its efficacy, Pinto implies that capitalism becomes a home, a conduit, for a conditional kind of agency for black women, for whom “law and rights” have never worked. In trying to extract cultural studies from its basis in a critique of capital, Pinto’s study points to a larger problem found in cultural studies as it manifested in the United States. British Cultural Studies was an important revision of Marxism, but was never a refutation of materialism. But in the United States, to quote Charisse Burden Stelly, a deep investment in capitalism and an entrenched Cold War commitment to its preservation created a current of cultural studies that ignored the class critique embedded in the British discipline, for which it was an ethical commitment.

Although I love a counterintuitive argument, celebrity and fame, or infamy, would not be the rubrics I would use to explore the “problem of rights,” not without more attention to what Pinto briefly acknowledges as celebrity’s “inarguable intimacy with capitalism.” (though Pinto does not take anticapitalism as her object of critique, rather Marx becomes her strawman, an undefined Marxism her mark). As many scholarly works demonstrate, we don’t need Marxism to have a healthy critique of capitalism or a class analysis. But an attention to materialism is urgent and essential in our current historical moment of violent inequity.

You cannot shed liberal humanism and keep capitalism, for they are yoked. Liberal humanism is part of how capitalism is articulated. I would also wonder at the ways modern forms of celebrity differ from the forms of notoriety explored throughout Infamous Bodies. Modern celebrity is bound up, constituted by liberal humanism: the reification of the possessive individual, the model of freedom based in competitive aspiration, wealth, and privilege. Yes, an old-school, white-boy Marxism is insufficient to examine our current world. Even as labor in many parts of the world remains power’s distributive center, capitalism’s multiplicities have turned all parts of our bodies, our thoughts and desires, into potential marketing opportunities. We are now in a world where everything and everybody must brand themselves, a very unfortunate choice of words when it comes to black women.

Pinto’s work also reveals a bifurcation in US Black Studies. Anti-capitalist strains in early black studies was all but subsumed, as Black Studies joined and became naturalized within the academy. Instead, a conservative lineage of class striving was shored up, one in which a figure such as Paul Robeson was all but forgotten (now lovingly remembered by Shana Redmond in Everything Man). But such black studies, that holds capitalism to account, has a long and resilient genealogy. Such a genealogy of black feminism can be traced, from the Combahee River Collective through the works of such scholars as Angela Davis, Hazel Carby, Ruthie Gilmore, and Stephanie Smallwood.

Pinto works with great nuance in many of her chapters, and I appreciate this challenge to a reductive argument. It is only in the last section that, as it turns to contemporary celebrity, this nuance in the text is lost. What Pinto calls no more than fitful reproach, or bad faith, is a critique that would acknowledge the ways a liberal feminist embrace of celebrity culture, represented here by Oprah, Beyoncé, Megan Markle, and the like, reproduces pernicious myths associated with a particularly acquisitive individualism in which success is defined by individual wealth. Empowerment becomes synonymous with financial savvy or some sort of charisma. The concepts of autonomy, agency, and legibility Pinto so carefully dismantles in the previous chapters rises up. We see how a very different moment in capitalism has shaped celebrity and made it more important than ever as its signature for the ruses of meritocracy and class aspiration. This ardent individualism blocks the ability for a more collective form of historical memory, one that would chart social movements rather than the success stories of black women who rose above “adversity” (racism, sexism, etc.) through hard work and natural (or enhanced) beauty.

This is in no way to deny pleasure, sexual desire, material joy, or effulgent, bejeweled excess. In fact, it is to claim not just desire, but its fulfillment, as a principle. Culture is not about labor but about the ineffable quality of sweat for pleasure, not profit. But in a world where everything is for sale, it is easy for this sweat to be packaged and sold back to us. Or for us to package our sweat and sell it, in packaging garnished with the iconography of radical opposition (raised fists and the like).

I agree with Pinto that “desire itself is the scene of the political.” But I don’t agree that celebrities like Beyoncé (or Opra, or Megan Markle or any of the others Pinto lists) “holds the space of desire, and the yearning to be desired.” Desire here, and yearning, rely on the idea of lack, and want, so central to acquisitive individualism. We need to think more carefully about what we mean by desire. Desire is too often considered as ahistorical phenomena, inherent to the body, authenticating. But forms of desire are not unchanging or universal. They are contingent on particular conditions; produced in particular ways through epistemological frameworks that congeal into ontological truths. What we desire, and how, are not pre-settings. Capitalist systems, which also change over time, canalize desire, and actually rely upon particular versions of desire, as acquisitive, possessive, as lack, and eternal want. What would make a diamond desirable, if it wasn’t its market value?

What if desire was not about acquisition and yearning, but about fulfillment and gratification? About mutual responsibility? Socialist utopianists argued for the “education of desire,” that we could learn to desire in different ways. Charles Fourier argued that the central problem in European social systems was the suppression of passions, and that the answer to the world’s ills was that it be organized around the fulfillment of all passions. But this fulfillment was also about collective obligation, to deem others’ pleasures as important as our own. As Audre Lorde makes clear in “Uses of the Erotic,” recognizing our collective needs, and wants, is just the beginning; such recognition she argues should then give rise to a culture of caring for each other as well as a politics that demands the dismantling of dominant power structures.

My biggest worry is that Pinto’s argument, which offers capitalism such indulgence, is out of step with the strong currents of thought and political desire I see in my students, and in the social movements now enlivening us all. I now hear abolitionist, explicitly anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, pro-sex positive, anti-heteronormative, anti-patriarchal critiques as part of a wide public parlance, and there is much less need for (heteronormative) royalty, or celebrity as a space for desire or political expression. There is a growing understanding that commodity culture does not provide a retreat or respite from a lack of legal and social recognition. I am heartened by this turn to a movement-oriented, rather than individualist-driven, politic. The turn here is not to a politics of inclusion, to law and policy, but away from it. It is a creative turn, one which embraces culture, and pleasure, as essentially political.

1.24.22 |

Response

Repetition and the Vulnerable Archive

In a recent essay about Natasha Trethewey’s and Claudia Rankine’s exemplary contributions to a post-Katrina Black feminist poetics, Sam Pinto and coauthor Jewel Pereyra argue that aesthetic work is a way not only to memorialize and bear witness to Black suffering and Black joy, but also to model an ethics and politics toward the mass consumption of Black pain. Part of their argument considers Trethewey’s volume, Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf (2010), a memoir composed in poetry, essays, letters, and photographs about the Gulfport, Mississippi, of the author’s childhood. Through both personal memory and poetic imagination, Trethewey shows the precariousness of the region and its inhabitants long before Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill brought those conditions briefly into national consciousness. Pinto and Pereyra consider her poem “Providence” (originally published in the earlier collection Native Guard), in which Trethewey recalls the annual news coverage of 1969’s damaging Hurricane Camille:

What’s left is footage: the hours before

Camille, 1969 — hurricane

parties, palm trees leaning

in the wind

fronds blown back,

a woman’s hair. Then after:

the vacant lots,

boats washed ashore, a swamp

where graves had been. . . .

Here and in other poems such as “Liturgy” and “Theories of Time and Space,” Pinto and Pereyra show how Trethewey’s work creates “spectral and architectural archives” in the aftermath of disaster by which Gulfport and its communities “resist their effacement across time” (7). Small lines of poetry and ephemeral gestures displace the archival news footage, with its cycles of destruction and renewal that yoke Gulfport to disaster capitalism and neoliberal ideology, even as swamp reclaims the community’s final resting places. Beside and beyond this, Trethewey composes a record of memorialization in different temporalities, such as the deep times of ecology and geography on the one hand, and “the far slower times of bureaucracy, incarceration, and decomposition” on the other (8). In the pages of Beyond Katrina, Gulfport itself shimmers as a what Pinto and Pereyra call a “ghostly and immaterial archive” that preserves the ways of living and losing that are willfully forgotten by dominant culture. “This incomplete, vulnerable archive,” they conclude, “is central to black feminist poetics and the work of recording how black communities, present in Gulfport for centuries, lived alongside and against history, natural and otherwise” (8).

I take this essay as a companion piece and important intertext to Pinto’s Infamous Bodies. But where Pinto and Pereyra describe a Black feminist poetics in the interstices of neoliberalism, the submersion of the gulf shore, and the fleeting evocations of memory, here Pinto describes a Black feminist theory through the durability of mass publicity and Black “celebrity.” The methodological approach and the ethical commitments, however, remain the same. Infamous Bodies traces the long representational afterlife of five Black women—Phillis Wheatley, Sally Hemings, Sarah Baartman, Mary Seacole, and Sarah Forbes Bonetta—as their images and stories become a genre unto themselves, one that transforms specific aspects of political philosophy within the aesthetic domain. Each of these women’s celebrity starkly exposes the incoherencies of key concepts in political philosophy—freedom, consent, contract, citizenship, and sovereignty—as they were unevenly embodied in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by people other than the European men for whom they operated. Indexing the underside of racial modernity while appearing on its surface, these celebrity images travel (in their own time and thereafter) across mass media and high art, television and literature, children’s cultures and state agencies, public debate and private letters, tourist productions and visual cultures, architecture and public memorials. From the eighteenth century through our contemporary moment, the circulation of their celebrity has been nothing less than an ongoing Black feminist counterpoint to Enlightenment modernity.

The US academy is another medium that reproduces their celebrity. Because their fame was rarely (if ever) self-authored and they had little (if any) control over their representations, they incite interpretation. Black feminist recovery projects and corrective histories sometimes endeavor to restore their autonomy by reading them as subversive figures who skillfully navigated their circumstances. At other times, such projects work to expose the mechanisms of their exploitation and dehumanization. Both of these stances, Pinto argues, produce Black feminist inquiries that take up the familiar generic conventions of “heroism” and “tragedy.” Posing an alternative to this, Pinto queries the “critical desires to read for repair and resistance” and turns to the aesthetic innovations of early Black women’s celebrity to “push against the assumed use of history as rescue, as corrective, as a critical mission of human rights and social justice” (19, 22). For Pinto, this “allows for a skeptical view of scholarly itineraries and opens up a flexibility in methods of interpretation—the questions critics feel we can ask while still maintaining deep ethical commitments to our subjects of study and to the complex world they have helped to create” (19). Celebrity, oddly enough, provides the conditions for displacing the genres of heroism and tragedy in narratives of Black women’s long and ongoing negotiation of agency and subjection.

What does this look like in interpretive practice? In her second chapter, Pinto examines the celebrity of Sally Hemings as an ongoing representation of the “scene of (un)consent” (building on the work of Saidiya Hartman) between Thomas Jefferson and Hemings (74). As the website for Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation estate and now a National Historic Landmark, explains, Hemings is “one of the most famous—and least known—African American women in US history” (https://www.monticello.org/sallyhemings). Hemings appears in the genre of celebrity as a fantasy projection and overdetermined representation, an “open secret” and disavowed spectacle that continually undoes the liberal humanist vocabularies of consent/non-consent (66). Taking Hemings’s (un)consent not as the conclusion of a story of resistance or subjection but as the point of departure for “imagining unconsent as the start of all political subjectivity,” Pinto reimagines Western political philosophy by placing Black women’s experience at its center (27).

Significantly, she achieves this reimagining (here and in the other chapters) by way of the aesthetic dimension. Pinto charts a long sequence of Hemings’s celebrity image and the political theory it enacts across a range of discursive forms and media: the rumors that circulated while she was alive and since; William Wells Brown’s novel Clotel (1853) and Barbara Chase-Riboud’s novel Sally Hemings (1979); the Ivory-Merchant film Jefferson in Paris (1995); Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman drama House Arrest (2003); Carrie Mae Weems’s art installation, The Jefferson Suite (1999); Todd Murphy’s edifice Monument to Sally Hemings (2000); Evie Shockley’s poems “wheatley and hemmings have drinks in the halls of the ancestors” (2006) and “dependencies” (2011), Lucille Clifton’s poem “monticello” (1974), and Natasha Trethewey’s poem “Enlightenment” (2012); tourist productions at Monticello; and a 2002 Saturday Night Live sketch featuring Maya Rudolph and Robert De Niro. Similar catalogs of contemporary aesthetic experiments with these celebrity histories shape the other chapters as well. These works collectively sound a contrapuntal political theory to the Enlightenment tomes of John Locke, David Hume, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, and Jefferson himself. And yet they are, in Pinto’s striking curation, less than the sum of their parts. They don’t add up to some complete picture, much less some truth. They eschew claims to mastery and remain in the indeterminate space of rumor, ephemera, and fragment. It is a recession rather than an accumulation, an anti-gestalt and a distribution across forms that allows the celebrity body to move through and against canonical political theory.

As Pinto tracks this resequencing of the Hemings story across different times and different forms, the chapter compiles what we can think of as an “incomplete, vulnerable archive” akin to the one Pinto and Pereyra describe in Trethewey’s Beyond Katrina. It is vulnerable in at least four senses of the word. First, based as it is in fiction, visual art, poetry, and other aesthetic registers, it is vulnerable to charges of fabulation (still meant as a pejorative term in most precincts, the transformative work of Hartman [2008, 2019] and Tavia Nyong’o [2018] notwithstanding). Second, because the archive comes together through Pinto’s attention to the celebrity status of Hemings and her argument for celebrity itself as a “genre of black political history,” it bears the stigma of feminized self-display, consumption, and inauthenticity (3). Third, while printed matter and visual culture make up some of the archive Pinto curates, much of it is also ephemeral and impermanent. Fourth, and most significantly, it is an archive of vulnerability—vulnerable bodies, vulnerable scenes, vulnerable histories. The interpretive practice Pinto models in her engagement with this archive is “to look at representation and culture not for a cure but for a question” to allow the conditions of “violence, trauma, desire, pleasure, risk, and vulnerability” to stand not as something to redress within the confines of liberal humanism but as a different vantage point from which to articulate a Black feminist politics (23, 22).

As she makes her way through these archives, Pinto announces her “commitment to staging different questions that ask us what ‘the changing same’ or ‘repetition with a difference’ mean, constitutively, about black feminist critical practices of looking, reading, and interpretation” (23). The transversal of form and genre that makes up Infamous Bodies’s vulnerable archives echo the changing forms and modes of the stories such archives tell. Method, theory, and object coincide. If we focus on the content of the Hemings/Jefferson scene of (un)consent, this archive documents its repetition. If we focus on form, however, we find something else. The archive appears not as a repetition-with-a-difference but a morphological transformation that alters not only the content of the Hemings story but also interrupts its repetitions and our rote critical responses to it.

***

Among the many ways to describe Infamous Bodies—a dazzling act of Black feminist theory, an interdisciplinary juggernaut, an archival tour-de-force, a moving curation of contemporary cultural works—it is also a noteworthy contribution to the field of performance studies. It is this contribution that I want to foreground here to think through how this book asks us to interpret the vulnerable archives of Black women’s modernity. Pinto is explicit about the influence of performance studies on Infamous Bodies, building her insights on the scholarship of Black feminist performance studies scholars such as Jennifer Brody, Daphne Brooks, Soyica Diggs Colbert, Jayna Brown, Uri McMillan, Amber Musser, Francesca Royster, and Anne Cheng. And the work in Infamous Bodies is prefigured by her own earlier research on Ama Ata Aidoo, Adrienne Kennedy, and Zora Neale Hurston in Difficult Diasporas (2013), as well as her more recent work on Beyoncé (2020). In order to think further about the curation of Infamous Bodies’s vulnerable archives and modes of interpretation, I want to place it beside two of the more enduring approaches to the diachronic study of embodiment, memory, and cultural transmission in the field of performance studies: Joseph Roach’s concept of “genealogies of performance” (1996) and Diana Taylor’s concept of “scenarios of discovery” (2003). Infamous Bodies draws on these approaches and also makes important variations that unsettle the relationships between media studies, performance studies, Black feminist studies, memory, and history.

For Roach, genealogies of performance track embodied acts of historical counter-memory, understanding “expressive movements as mnemonic reserves” (26). Performance genealogies attend to “the disparities between history as it is discursively transmitted and memory as it is publicly enacted by the bodies that bear its consequences” (26). It is a method to trace the discontinuous routes by which such counter-memories persist across time and space through “kinesthetic imagination, vortices of behavior [spaces dense with social memory], and displaced transmission” (26). Genealogies frustrate the search for origins and purity, finding instead ongoing improvisations of cultural hybridity that persist in performance even if their beginnings are shrouded in myth or otherwise forgotten. Taylor offers a complementary framework for performance history in her concept of “scenarios.” Scenarios are “a paradigmatic setup that relies on supposedly live participants, structured around a schematic plot, with an intended (though adaptable) end” (13). These are theatrical, recognizable, and repeated over time. They include literary elements such as narrative and plot, but also “corporeal behaviors such as gestures, attitudes, and tones not reducible to language” (28). The reenactment of such highly theatrical scenarios of discovery structure, for instance, colonial encounters in the Americas from the fifteenth century through the present.

Infamous Bodies draws on and varies frameworks such as Roach’s genealogies and Taylor’s scenarios to respond to the vulnerable archives that the book compiles. As she explains in the introduction to Infamous Bodies, Pinto seeks in these historical celebrities and their afterlives “alternate sequences of meaning and strategies of interpretation that include but do not center on the stories critics already tell and know about the aims and possible outcomes of black political and social life (and death)” (6). This approach—let’s call it sequencing—rethinks the relationship between repetition, Black studies, and performance studies. This sequencing of meaning maps the components of Black women’s celebrity images and their rearrangement into new configurations, offering insight not only into each chapter’s featured figure but the cluster of anxieties, desires, fears, and pleasures that she incites across decades and centuries.

Sequencing and genealogy are overlapping ways of tracing modes of embodied memory and cultural transmission across time and space, but with somewhat different emphases. Genealogies of performance emphasize the continuities of forms of transmission even as the content may be displaced or its meaning forgotten. Pinto’s sequencing of performance emphasizes the continuities of content even as they appear and reassemble across different forms. Art installation, rumor, historical fiction, poetry, comedy sketch, and architecture: Hemings’s Black celebrity and the scene of (un)consent that her star image conjures traverses these forms as it is re-sequenced and remixed. Curated by Pinto, Hemings’s vulnerable archive continually rearranges the elementary unit of each celebrity image in creative variations that produce new arrangements of Black celebrity and of political economy. It provides not only a genealogical “history of the present” but also new routes toward the future.

Etymology offers us further insight into this sequencing. Prior to the kind of genomic sequencing that Weems scrutinizes in the long shadow of Hemings’s “scene of (un)consent” and the truth claims of positivist science, we find an aesthetic meaning to the word sequence. In ecclesiastical Greek, sequence was used to describe a neume or melisma—the singing of one syllable across a succession of notes (OED). This is a kind of vocal run, or flight, of notes that allows for sonic movement within the unit of the syllable. Neume itself is derived either from the Greek word pneuma (for breath) or neûma (for sign); as Pinto explains early in the book, the “bodies” of her title signifies “both the material body and its representational insistence and repetition,” both breath and sign (4). In response to the long shadow of Hemings or Phillis Wheatley or Sarah Baartman or Mary Seacole or Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Pinto compiles a vulnerable archive that riffs on the celebrity image and decodes the building blocks of Blackness and Enlightenment that enact the stance toward politics that she describes.

This sequencing of the meanings of Black women’s celebrity is itself allegorized in her discussion of Weems’s The Jefferson Suite, which for Pinto “decenters consent” from the retelling of Hemings’s fame (88; see images here: http://carriemaeweems.net/galleries/jefferson-suite.html). Weems created this art installation in the wake of the “Y-chromosome haplotype DNA study conducted by Dr. Eugene Foster and published in the scientific journal Nature in November 1998” that used genomic evidence to confirm that the third US president fathered at least six children with Hemings (https://www.monticello.org/thomas-jefferson/jefferson-slavery/thomas-jefferson-and-sally-hemings-a-brief-account/monticello-affirms-thomas-jefferson-fathered-children-with-sally-hemings/). Weems’s installation took the occasion of this new entry in a two-hundred-year controversy to meditate on the positivist claims of science, reproduction, and biology in the long history of race-making and white supremacy. The exhibition was made up of eighteen floor-to-ceiling muslin sheets with digitally printed photographs. Several of these banners bore images of figures with their backs to the viewer superimposed with one of the four letters (C, G, A, T) identifying the nucleotides in a DNA strand. Among these anti-portraits were other images that evoked the public life of DNA: Charles Darwin, Dolly the Sheep, Timothy Wilson Spencer (the first person executed for a crime proven by DNA evidence), and a recreation of Thomas Jefferson at a writing desk gazing upon Hemings with her bare back turned to the viewer in an echo of the other scrims.

The contrast between the certain “proof” of DNA and “hard” science, on the one hand, and the banner’s thin fabric, the display of flesh, and the ambiguity of rumor, on the other, provide the exhibition with its epistemological tension and archival vulnerability (88). What does it mean to decenter consent from the iteration of Hemings’s story? In this exhibition, it is to sidestep either/or, agency/subjection frameworks of interpretation. The Jefferson Suite, Pinto writes, “insists less on of an up-down, social-death-or-sexual-pleasure model, with its walk-through design acting as a way of experiencing multiple stories of Hemings and her legacy across these binaries. The pieces stage the significance of Hemings’s sexuality to understanding not just a chronic lack of agency for black women but the ways that the uneven terms of enslavement and social death also created complicated strains of US experience, at the cellular level” (88). In unmaking the familiar genres of Hemings—heroic, tragic, romantic—Weems grounds her work on the overdetermined genre of celebrity and its surface relations to aesthetically resequence the genetic material of this national “primal scene” (26).

Such sequencing (with its suggestion of the musical sequencing technologies that record and mix sound) also extends “performance” into the realm of mediation, where the body itself may be crucially absented, even while embodiment remains. Consider Pinto’s inspired argument about Todd Murphy’s Monument to Sally Hemings, a massive steel-frame scaffold placed on top of the Charlottesville Coal Tower (and thus across the way from Jefferson’s dome at the University of Virginia). Murphy draped the structure with a delicate, ghostly fabric that hung as if from a seamstress’s dress form to create an enormous specter above the pastoral landscape. For Pinto, this nonmimetic “strategy of reading sexuality without bodies—a scene of (un)consent without sex—offers us a way to recalibrate/resequence thinking about the centrality of arguments about agency and black women’s subjectivity to not just include sexuality, but to imagine sexual desires as places to renegotiate the very conceptualizations of freedom, where proving and disproving agency is not the end question of political and social ‘life’” (88). Turning the Foucauldian call for a shift from “sex-desire” to “bodies and pleasures” on its head, Pinto demonstrates how resequencing Black women’s celebrity can show us its encounter with liberal humanism in new forms. The body remains central, but not necessarily the presence or liveness that performance studies often assumes. This sexuality without bodies and performance without copresence are just two unexpected instances of what the sequencing of Black women’s celebrity can create.

These “incomplete, vulnerable archives” of Black celebrity, that is, sequence the strands of a fantasy DNA that stands in aesthetic contrast to the positivist claims of biological DNA, as in Weems’s The Jefferson Suite. This is a living archive, one that draws on and mutates the historical archive. Infamous Bodies updates and offers new insight into the histories of repetition-with-a-difference or changing-same that have shaped Black studies and performance studies. Each chapter draws on this method of sequencing to show how minoritarian aesthetics are a location of the political from the first. While building on genealogies and scenarios, Pinto’s sequencing tracks the ongoing encounter between Black women’s celebrity and liberal humanism. It is a Black feminist method that takes the sensuous dimension of minoritarian aesthetics as constitutive of political subjectivity. What this amounts to is nothing less than a resequencing not only of early Black women’s celebrity but also Black feminist intellectual traditions and of the political as such. It takes modern political philosophy’s genetic material—freedom, sovereignty, contract, consent, and citizenship—as problems and questions for Black feminist theory, rather than states to be claimed, granted, or withheld. In this way, Infamous Bodies reminds us of the value of “the vulnerable, world-making capacity of fantasy,” and of minoritarian aesthetics as a sustaining condition of political subjectivity (65).

Works Cited

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York: Norton, 2019.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12.2 (2008) 1–14.

“neume, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press. December 2020. www.oed.com/view/Entry/126352. Accessed 10 December 2020.

Nyong’o, Tavia. Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Pinto, Samantha, and Jewel Pereyra. “The Wake and the Work of Culture: Memorialization Practices in Post-Katrina Black Feminist Poetics.” MELUS 44.3 (2019) 1–20.

Pinto, Samantha. Difficult Diasporas: The Transnational Feminist Aesthetic of the Black Atlantic. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Pinto, Samantha. “‘I Love to Love You Baby’: Beyoncé, Disco Aesthetics, and Black Feminist Politics.” Theory & Event 23.3 (2020) 512–34.

Roach, Joseph. Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Trethewey, Natasha. Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

1.31.22 |

Response

Sweet, Sweet Fantasy Baby

Samantha Pinto’s Infamous Bodies is that rare scholarly work: smart, funny, and important. Taking on such varied topics as the foundation of rights in the liberal democratic West, the category of the human, and the notion of celebrity, Infamous Bodies casts the past and present as entwined through the relations among the infamous black women who appear throughout the text as time travelers: Phillis Wheatley, Sally Hemmings, Saartje/Sarah Bartman, Mary Seacole, and Sarah Forbes Bonetta. As much a reflection on the contemporary, in which figures like Beyoncé, Michelle Obama, and, most recently, Amanda Gorman “cause all this conversation” (Knowles, “Formation,” 2015) as a historical review of the (after)lives of famous figures, Infamous Bodies compellingly argues black “celebrity becomes a particular genre of black political history, one that foregrounds culture, femininity, and media consumption as not merely reflective of, ancillary to, or compensation for black exclusion from formal politics, but as the grounds of the political itself” (3).

There is so much to love in Pinto’s book, from its sprawling temporal scope, which covers texts and figures from the eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, to its piercing critique of the foundations of (Western) rights and freedom. For example, in her consideration of the transformation of Sally Hemmings’s private room and entrance to Thomas Jefferson’s quarters in his Virginia plantation, Monticello, into a bathroom, Pinto describes the actions of the (white) “preservationists” as “laughable in its irony and its transparently racist and misogynist motives, let alone in its abjectionist replacement of the history of enslaved women’s sexuality with the site of human waste relief” (90). Here, and throughout, then, Pinto’s distinctively witty style evokes wry laughter as it pierces the heart of centuries of racial injustice in the Atlantic world.

What is most compelling about the book and the breadth of thought behind it is its critique of fantasy in liberal humanist discourses of rights, property, and other theories of the political. Often interarticulated with a theory of desire, Pinto highlights how fantasies of white, male, and liberal personhood emerge from the “conflat[ion of] rights with the absence of risk.” “Such an overdetermining structure creates a political situation where to let up any pressure on the constant narrative of black suffering, risk, and injury feels like one is giving up on a political future, save for minor pauses for black excellence or triumphs over overwhelming antiblackness” (19). Here, Pinto highlights the speculative qualities—the regressive fantasies—of liberal democratic discourse. The who and what of rights-bearing, as has been discussed by various black feminist legal theorists, including Cheryl Harris, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Patricia Williams, is what produces white risk, white security, and ultimately, whiteness. In Infamous Bodies, fantasy functions in the economy that entangles “relations,” “resources,” and “desire” (35). It is ultimately through fantasy and an “imaginative reading practice” that Pinto is able to excavate and examine the archive of vulnerability. As she writes, “[Fantasy] is not a fiction, not wholly controllable or intentional, and yet it provides a frame, many frames, for interpretive practice as itself a desiring act of projection, longing, resource, and sociality” (35). As such, ideas like freedom and consent emerge as simultaneously slippery and “sticky” (36), both capturing the imagination as socially and political productive concepts and at the same time slipping beyond the grasp of the real. Pinto is careful to disambiguate the psychoanalytic valence of fantasy from its use in cultural studies and yet, I wonder if the distinction between fantasy as it appears in black feminist and black radical theories as compared to the psychoanalytic implications is as tangible as Pinto describes. As a matter of worldmaking, the psychic dimensions of fantasy seem to cling to worldly possibilities even as they invent and invest the violence of racialized encounters, whether through the birth and proliferation of rights discourse, the construction of the human as a political and social being, or the rendering of social relations as contract relations between rational beings. As such, I don’t see Pinto as really disambiguating fantasy from the radical matrix of black feminist / black radical worldmaking, but rather as bolstering the political dimensions of fantasy with the more personal psychic intimacies of unknowable figures like Wheatley and Hemmings.

Pinto’s ironic juxtaposition of intimacy and unknowability critically informs my understanding of her efforts to mobilize the affective register of vulnerability and insecurity in the service of undermining core principles of liberal democratic discourses—rights, freedom, consent, etc. By positioning two opposing forces—intimacy and unknowability—in relation, Pinto posits a reading practice that emphasizes vulnerability as its affective dimension. Here, Pinto takes up the challenge laid down by Saidiya Hartman in “Venus in Two Acts”; that is, how to conjure, bring forth, or otherwise evoke the presence of figures erased from history without redounding the harm of that erasure. For Pinto, the same problem presents on a slightly different order: how to make sense of the affective contour of “infamous” black women’s lives, when those contours have been quite literally whited-out. What Pinto proposes is a way of reading that eschews “a race to the bottom” in favor of one that imagines the ground of black life in all its indeterminate vulnerability as the substrate “constitutive of political subjectivity” (22).

The archival traces of vulnerability, especially in their uneven accretion in black women’s bodies, extends the critical perspective of Hartman, black feminist legal theorist Patricia J. Williams, and others, including speculative fiction author Octavia E. Butler. Collectively engaged in a shared project of historicizing affect and of felt history, these works demonstrate the importance of understanding the relationship between vulnerability as a historically and socially specific concern, and the conditions that generate it as an affective sensation. In her work on Octavia E. Butler, Aida Levy-Hussen explains that in Kindred, Butler’s 1979 neo-slave narrative, Butler set out to write a story that would enable people to “feel slavery” (Levy-Hussen 68) and describes Butler’s work, and especially its hinge around the protagonist Dana’s killing of her white, slave-owning ancestor Rufus, as provocative if ambiguous in its ability to achieve that end (74–76). Yet, what Butler does achieve, throughout her oeuvre, and especially in her Kindred is something very close to that historical feeling, one that Pinto marks out as disorienting and incoherent. In her ambition to imagine the feeling of the “afterlives of slavery,” Butler can’t help but fall short, just as Pinto asymptotically approaches, without ever truly reaching, the interior life of her infamous women. This is not a critique, but rather an essential way of reading and thinking black feminist ethics, especially with regard to the “uses of history.” This is also true of Butler’s work in Dawn (1986) which (as I describe elsewhere) hovers over without ever touching down on the question of consent (Mann). Pinto’s description of consent in terms of “romance,” which flags both the formal/generic literary conventions on the one hand and the more elusive amorous and libidinal valences on the other, strikes to the heart of both Dawn and Kindred in which Lilith’s and Dana’s circumscribed “choices”—their relative abilities to opt in and out of certain forms of labor—are totally circumscribed. What Pinto articulates in her discussion of Hemmings is not an abandonment of the notion of consent then, but rather a rich and rigorous historiography that enlivens how we think about and relate to Butler’s work.

Patricia J. Williams’s work can help us understand this pervasive ethic in black feminist theorization of the uses of history in excess of the “corrective” (Pinto 25). In The Alchemy of Race and Rights (1991), Williams, who Pinto engages with throughout Infamous Bodies, engages in a similar reading praxis. Williams, describing her own efforts to manifest the absence of her black and enslaved great-great grandmother in the jurisprudence and personal correspondence of her white male ancestors, writes, “I see her shape and his hand in the vast networking of our society, and in the evils and oversights that plague our lives and laws. The control he had over her body. The force he was in her life, in the shape of my life today. The power he exercised in the choice to breed her or not. The choice to breed slaves in his image, to choose her mate and be that mate. In his attempt to own what no man can own, the habit of his power and the absence of her choice. I look for her shape and his hand” (Williams 19; Nash 102–3). Here, I see Williams engaging in what Pinto names a vulnerable “political and reading practice” (20) that “takes seriously, politically, the desires and attachment to the very systems that fail us” (21). For Williams, the synecdochal relationship between shape and hand remind us of the specifically-oriented object-subject dyad, through which her great-great grandmother is drawn into existence by her great-great grandfather’s pen. We read the echo of this desire to draw out elusive and resistant traces of black women in Pinto’s discussion of fantasy. This is especially true of fantasy’s relationship to history, a connection captured in Williams’s search for ancestry and lineage, a quest that ends, as Pinto reveals, not merely in the individuated discovery of a contract—in Williams’s case, the “contract of sale for [her] great-great grandmother” (17)—but in the very foundations of contract theory. Black vulnerability is not, as Pinto details, a by-product or second-order process of social relationship, but its bellwether. In her words, “contract, then, entails the promise of the good life beyond enslavement, even as it occludes and often forecloses the actual resources, including cultural capital, needed to attain such a fantasy or what the ‘fantasy’ of freedom . . . entails” (115). Speaking in this case about the reproduction of the trial of Saartje/Sarah Baartman in the film Venus Noire, Pinto concludes that the depiction of Baartman’s body does more than “reexploit her.” Instead, the film proposes an alternate mode of understanding: “Rather than think of the jarring, insisted redisplay of Baartman’s body as reexploiting her, then, one can read the film as imagining embodied exploitation—of labor, of sexuality—as the vulnerable state of being that Baartmaan exposed as the paradigmatic subject of Enlightenment modernity, with its fictions of law, contract, and the order of sociality” (116).

The duet of fantasy and fiction that invest power and vulnerability in some places and not others is perhaps the most striking and important aspect of Pinto’s and is also the site to think the prospects of the fantastic and speculative, not merely in the context of genre fiction and culture, but also in our approach to the histories of figures, infamous and otherwise, and the ideologies and affects that saturate their time and ours. Calling to question the taken-for-grantedness of race-and-gender dyads that continue to construe white heteropatriarchy as the zone of Reason, Law, Justice, and black women’s racialized and gendered lifeworlds as somehow alien to these concepts (despite decades of critique to the contrary), Pinto urges us to see the traces, however fine and indistinct, of the “cultural but also political labor” black women celebrities, both past and present, perform (204).

Works Cited

Levy-Hussen, Aida. How to Read African American Literature : Post-Civil Rights Fiction and the Task of Interpretation. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Mann, Justin Louis. “Pessimistic Futurism: Survival and Reproduction in Octavia Butler’s Dawn.” Feminist Theory 19.1 (2018) 61–75.

Nash, Jennifer C. “Writing Black Beauty.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 45.1 (2019) 101–22.

Pinto, Samantha. Infamous Bodies: Early Black Women’s Celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

Williams, Patricia J. The Alchemy of Race and Rights. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Response

Black Feminism in the Air

Dear Jennifer, Jayna, Shane, and Justin,

I want to begin with acknowledging my work, and self-consciously this response to your generous reactions to it, as a continuation of the form and content of your own scholarly inquiries (as well as many others across Black feminist studies). So I extend Jennifer’s form of a letter and her welcome familiar address, and I begin on her calling up of Lorraine O’Grady’s photographic diptych from her “Body Is the Ground of My Experience” series:

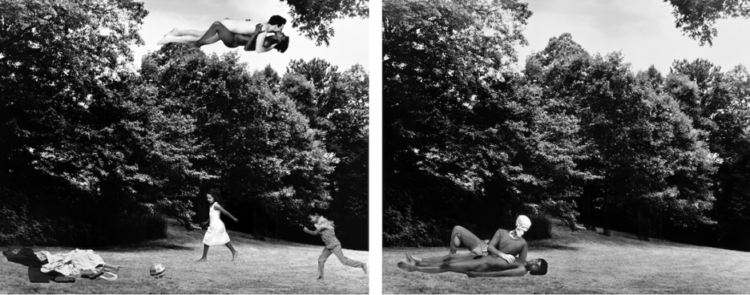

Body/Ground (The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me), 1991/2019

Archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Baryta pure cotton photo rag paper

40h x 50w in

Last located on 10/2/2021 at http://lorraineogrady.com/slideshow/body-is-the-ground-of-my-experience/#jp-carousel-1568

This thrilling piece challenges beyond measure, making literal the rapturous legacy of Jefferson and Hemings’s entanglement as the air we in the US breathe, the very stuff of race that infuses quotidian, intimate life. That the rumpled heap of clothes/costuming exists in material form on the grass on which Black children play on the left panel, “Green Love,” all free limbs and bare feet, signals the inevitability and the threat of anti-Blackness as the “ground” from which Black life and subjectivity springs. The eroticized floating figures, grounded and plasticized in the second frame, “Love in Black-and-White,” hover as eroticism is wont to do—diffuse, vulnerable, exposed, awkward. Here we “see” Sally Hemings, perineal symbol for how black women’s sexuality and their experience of sexual violence undergirds—indeed produced—a nation and a national imaginary. Here we “read” Lorraine O’Grady, visual provocateur, insisting on uncomfortable juxtapositions that merge play/humor with the terror that infuses Black feminine embodiment and Black representation—its promises, its pitfalls, its futures, its violences, its occlusions.

O’Grady’s image, called to by Jennifer, is one of so many omissions in Infamous Bodies as it dashes through contemporary archives of early Black women’s celebrity (the dizzying amount of renegotiations of Sarah Baartman in particular haunt artistic and scholarly space, and me in my inability to keep up with the variations on my own willed theme). These omissions speak to my failures as a scholar as well as the risks Infamous Bodies takes on to make a critical and I think crucial argument about taking feminine/feminized culture seriously in the study of Black feminist thought without constantly translating it into political categories as we already recognize them—the resistant, the tragic, the free, and the fugitive being some that contour the boundaries of interpretation that, I argue, these early figures and their subsequent re-representations chafe against. As Keguro Mancharia has so recently argued, friction or frottage isn’t necessarily “bad” or oppositional when we think of the space of queer and femininized work—conceptually, aesthetically, politically—across the Black diaspora. It’s not without pleasure, even as it escapes easy celebration or calibration. Frottage is what we see in O’Grady’s vision—physically, of course, but also in the play between the organic and the inorganic, fantasy and realism, materiality and immateriality, interiority and opacity.

I follow the paths of Jennifer’s work, from Impossible Purities’ insistence on the Black feminine presence in Victorian transnational culture to her formalist call to Black expressive abstraction in Punctuation to her gorgeous recent work on Edmonia Lewis that inspired this book in its focus on the outrageous presence of Black queer women on the historical scene of high art; Jayna’s work that traced early the divergent paths that Black chorus girls and musicians took through early twentieth-century diaspora sound and performance cultures (and her new and exciting book on Black musical utopias); Shane’s careful and groundbreaking work on the history of intimate performance and Black diaspora gesture in the popular embodiments of black feminine and queer forms across both of his books; and Justin’s insistence on unpacking black feminism’s unexamined attachments to the security state alongside his reading of speculative work that world-breaks. All grapple with vulnerability and failure in such deep ways. I’ve followed your collective scholarship onto a thorny path that has entailed friction between sacred binaries of Black study like enslaved and free, radical and capitalist, subject and object that, in particular, Jayna and Jennifer are pushing me to speak on here. I follow Justin and Shane’s uncovering of the significance of the body-that-isn’t-a-body in my work’s methodology, ethics, and imagination—the ways that I am grappling with fantasy, desire, repetition, non-liveness and a critical will to recreate the real/realism that grip the field and won’t let our questions, our interpretations, range. A thorny path, a path where the frottage between the poles of some of these treasured binaries slips into uneasy contact and relation, cannot and should not erase stark and structural differences between them—it shouldn’t collapse into relativity or erase violence.

In trying to trace the animations of early figures of black feminism across the contemporary, I hope instead that what I’ve done is highlighted the ways that scholarship and political discourse as well as expressive culture have often mobilized early black women celebrity figures too starkly into one side or the other, not allowing for the slippages that, as O’Grady’s intentionally unreal photographic rendering of the scene of Jefferson and Hemings stages, are so diffuse as to not allow for an outside. Rather, black women’s historical and difficult embodiment is all-encompassing, the air we breathe; it is the economy under which all of us produce, consume, and interpret the world. My move in Infamous Bodies is to suggest a way of thinking about the ways that our world, writ large as modernity, was and is formed through black feminine subjects in all of their complexity and legal/cultural limits—black women and their embodied experience, performances, & representations as the basis of all political subjectivity, rather than as the constant signs of political lack. What happens if we can acknowledge the acute structures of enslavement and freedom even as we don’t venerate or flatten the experience of either for Black women across modern diasporas, including the ways that “freedom” was figured through fictions of contract labor, marriage, and other customary violent norms that liberalism continues to paper over through rhetorics of choice and autonomy (see the brilliant work of Natasha Lightfoot, Jessica Millward, and Bianca Williams among others on this not-quite-split)? The vulnerabilities of Phillis Wheatley and Sarah Forbes Bonetta were achingly different in structure, form, and content—and yet the cultural work they did for themselves, for their worlds, and for our historical and contemporary appetites for re-presentation now can be put in thorny, frictive conversation that goes beyond absolutes that reify “freedom” as the ultimate and unquestioned goal of black feminist study.

By suggesting vulnerability as one possible Black feminist political pathway, both future and past (and alongside scholars Kimberly Juanita Brown, Martha Fineman, and Alexandra S. Moore), I aim to figure something like an acknowledgement of the impossibilities of disentangling the competing markets for Black women’s objectification, consumption, and self-making. My will toward descriptive density I’m sure fails in various spots as it tries to mark how generations of black feminist producers and audiences made, fashioned, consumed, and found meaning in the feminized commodity culture of celebrity (something that Aria Halliday will dig into in her forthcoming book, Buy Black). It’s uncomfortable to read both these historical figures and our more contemporary reanimations of their legacies as bound, attached to, and invested in institutionality in various suspect forms, let alone to argue that perhaps scholarship in the field remains unconsciously attached to these conceptual and cultural markets as well. My own work, particularly my first book on formally innovative Black women’s writing, is no exception. I find my own practices reactionary to the methods and modes of the times, ending up again and again engaging in the thing I disavow. This new book, I hope, thinks on that tenderly for myself and others; of course I have my critical attachments that leave me vulnerable, that I wish to secure even as I question critical attachments to security that haunt black feminist studies, understandably so.

Here, I follow a range of scholars not just on the counterintuitive work on black performance culture like Jennifer, Jayna, and Shane alongside Daphne Brooks, Nicole Fleetwood, Michelle Stephens, Anne Cheng, E. Patrick Johnson, Amber Musser, and others, but also Black feminist scholars across disciplines like Bianca Williams in The Pursuit of Happiness, who marks national, sexual, and class tensions amongst Black diasporic subjects not to make heroes or villains—or to narrate dupes of the system. Her work negotiates the lure of ruse-or-resistance when examining how Black women engage with capitalism and the often-meager protections, loopholes, or comforts it offers. I hope that in any small part, Infamous Bodies manages to acknowledge but also decenter binaries like capitalism/anti-capitalism, slavery/freedom, colonialism/sovereignty in ways that try to stay specific and grounded but also draw on new intimacies, like Lisa Lowe’s comparative work on the long legacy and many different forms that scenes of subjection take in the 18C and 19C. I see my own work as a humble piece of scholarship in this vein, describing rather than designating my subjects to reorient the perception of modern subjectivity toward the complex embodied experience of being and being read as a Black woman. I know that existing work by Erica Edwards and by Justin has done this so much more powerfully and eloquently than my own, and joins the scholarship of my brilliant friend and collaborator organizing these essay reflections, Jennifer C. Nash, alongside Jenny Sharpe, Ann Laura Stoler, Brenda Stevenson, Emily Owens, Lisa Ze Winters, Kali Gross, LaShawn Harris, and others working on the difficult subjects and subjections of the eighteenth and long nineteenth centuries, as well as of the contemporary era.

I think about this method of mine as stemming from Elizabeth Alexander’s gorgeous “The Venus Hottentot (1825),” a poem I have yet to be able to put down or push away from any of my work, no matter how varied the projects. Framed by a devastating part 1 of clipped couplets on Sarah Baartman’s dissected body from the perspective of comparative anatomist and racist George Cuvier, part 2 turns to the interior address of Baartman herself, declaring, “I am the family entrepreneur!” Even while and as and because she is framed in the gaze of Cuvier, Alexander’s Baartman moves away from any easy celebration of “home,” kin, and community. Kaiama Glover’s recent work, A Regarded Self, is a brilliant meditation on the value of self-regard in theorizing Black Caribbean women’s cultural and political visions away from community. Emphasizing the physical and psychic labor of reception, interpretation, production, and performance, Alexander and Glover dwell in an electric version of Kevin Quashie’s articulation of a black interior of impulses, desires, and dreams—many of them “quiet,” but no less alive or unreal. And I think about the stretch between the poetic Baartman’s exuberance about travel, her regard for her linguistic prowess, her wish to send new tastes back to her brother and Alexander’s crucial work now running the Mellon Foundation and reinvesting capital in the reimagining of institutional life across this country and I see a string of difficult and tender and loving and worthwhile connections to the questions these early black women celebrities begged of me and my political vision while writing Infamous Bodies. Alexander, and Alexander’s Baartman, don’t reside in an outside. They make with what is, when what is, is tainted, violent, messy, impure. Infamous Bodies doesn’t suspend critique but nor does it imagine it is outside of it. It imagines that we are all inside the world that Black women, and Black feminism, has built.

We risk lessening the grip of long cherished or stalwartly bad objects of our field in refocusing on the complicated afterlives of compromised figures. My students seem to grasp this deeply, as they are as interested in BLM as they are in what Michelle Obama was wearing at the inauguration or what Mariah Carey is doing, period. Though they are anti-capitalist, they celebrate the pleasure, beauty, style, and care offered to them through capitalist marketplaces with abandon. They wear their Fenty lipstick to the protest. They don’t see representation as a zero-sum game of inside and outside, with the commodified feminine always provoking skepticism in the face of “real” or “radical” politics. I see their ability to hold both reflected in the brilliant work that all of you do on literature, performance, art, and music: the giddy smart play of Babylon girls and Black musical worlds (Jayna); the exuberance of punctuation and the lure of performing purity alongside the sculptural heft and design of black and indigenous life (Jennifer); the political significance of the fleeting, the shiny, the fad, the niche, the objectified, the inorganic but no less luminescent intimacy of performance within capitalism (Shane); the speculative play and incandescent apocalypses of Black feminist imagination (Justin). I have found, in your collective scholarship, a path to emphasizing the affordances of celebrity, and of Black feminism, and of Black women’s subjectivity, and even of capitalism for Black women. Through that route, I’ve been able to emphasize the work of performance, of public relations, of celebrity and celebrity reception as labor—thinking through forms of feminized labor that refuse narratives of false consciousness and in so doing need to describe relations to history, to economy, to image differently.

But I sit here in 2021, in my Zoom closet upstairs. I sit here in 2021, in my Zoom closet, employed and able to pay the deductible for the destroyed house below me, property gutted by a burst pipe, which was gutted by infrastructural failure of a capitalist energy plan that preyed on the most vulnerable “customers” of a necessary utility. I sit here in 2021, post-Covid diagnosis and post-vaccine in a lucky and privileged body that reckons with the global continuance of the pandemic and the inequities it laid so bare, here in the United States and abroad. I sit here in 2021, exhausted by the year of endless childcare and home-schooling of my young kids, massive online classes, illness both mental and physical, structural damage to my home, no rest, no rest, no rest. It’s relentless, even in my little world, even on my “yacht,” as my brilliant friend Judy Coffin refers to our lot as tenured professors at a research institution. I sit here thinking about the conditions of now, thinking about the ways I’m bound, the ways I can never be bound or understand/feel some binds as a white woman, the binds that I’ve escaped and those that I’ve chosen. I sit here in my Zoom closet in my destroyed house in this Covid upheaval and racial reckoning and I think about the conditions of boundedness, of weakness, of vulnerability that propel scholar and public official Alondra Nelson to declare, “Never before in living memory have the connections between our scientific world and our social world been quite so stark as they are today.” I sit here and I am overwhelmed that all of you, undoubtedly operating beyond capacity, took the time to read and think and write on my work.

I want to take this moment to thank all of you—Justin, Shane, Jennifer, Jayna, and Jen—for your gorgeous words and your time with my work during this endless and exhausting time. You took time to be tender to and with the thorniness of Infamous Bodies—by description, by renarration, by questions, by exposure of its weaknesses and possibilities. I think of this book as one that taught me as a scholar to be tender with attachments and dreams that don’t center even as they include forms of freedom—that might embrace the temporary, the fleeting, the ambitious, the self-interested, the bad, and the bound, and to do so knowingly. I wanted to challenge my own romances of community (h/t Miranda Joseph)—historical, political, intellectual—that I bound my subjects in and have my own attachments to, but to do so without diagnosing these figures or our reception of them as either suffering under false consciousness or cruel optimism or as exhaustedly resisting the normative. I wanted to sit with these five figures, these early Black women celebrities, in all of their vulnerability and imagine a critical practice that could earn a seat alongside their difficult experiences and re-animations. As a student of Black feminism, I wanted to sit with all that I didn’t know and didn’t let myself understand or see about the very air around us that is made up of O’Grady’s scene—confronting, cheeky, haunting, disturbing, beautiful, absurd, cutting.

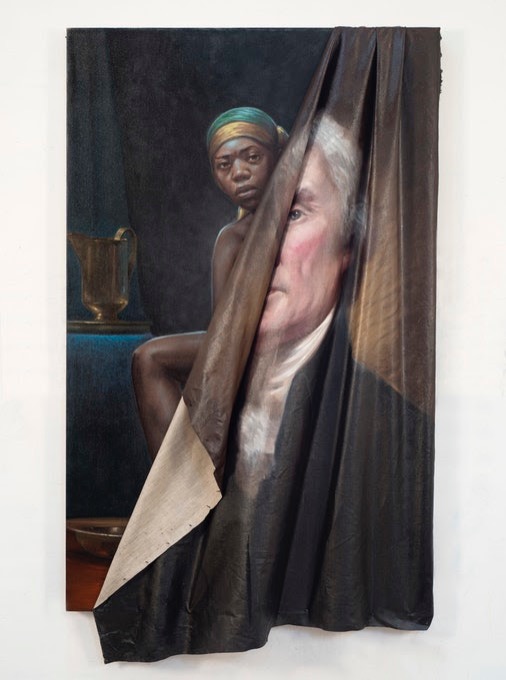

O’Grady, reflecting on her own long overdue retrospective, recently said, “I feel that I’m working on the skin of the culture and I’m making incisions.” Scholar Marcia Chatelain recently shared some of the ways she teaches US presidential history through visual forms, including this painting by Titus Kaphar:

TITUS KAPHAR, “Behind the Myth of Benevolence,” 2014 (oil on canvas)

Collection of Guillermo Nicolas and Jim Foster, © Titus Kaphar. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Last accessed on 10/2/2021 at https://www.culturetype.com/2018/03/28/titus-kaphar-and-ken-gonzales-day-explore-unseen-narratives-in-historic-portraiture-in-new-national-portrait-gallery-exhibition/

Pricking, slicing the skin of the liberal humanist vision of Jefferson requires exposure, yes, but also a tenderness for all that makes up that legacy—the enslaved and free Black subjects who labored, loved, entangled, resisted, laughed, and lived with and in proximity to him and in the world he imagined then tasked them to make around him. Tenderness here means attention, responsibility, kindness, generosity and also a description of sensation, of what hurts when pressed—as well as tender, a form of currency, a mode of offering or exchange. “Body” in O’Grady’s title grounds. It is material in all of its forms, even the most difficult and tentative. It can still hurt even as and through care’s presence. Tenderness cannot be cured or secured against. It’s an undoing and an identification. Behind and beyond the reveal of the Black subject and Black aesthetic and cultural expression shaped by, through, with, against, and away from Jefferson’s political vision, what can we let Black feminine subjects be and feel, and how can that be the base of a political history and political imagination that doesn’t insist on rights and freedom in Jefferson’s wake? Those rights and freedoms, and those terms, were always imagined at and as the cost of gendered, racialized, sexualized, and classed service to the free subject—as the only strategy for imagining either the world as it is or as we might want it to be. I wish to relentlessly expose my critical assumptions of what a good life might have been or could be to the power of thick description without flinching, to the incisions of O’Grady’s eye and materials, as these early black women celebrities insist on and repeat.

With so much gratitude,

Sam

Jennifer DeVere Brody

Response

The Racial Lure of Transnational Bodies

Dear Samantha,

I write to you while sitting in my office in Oakland (unceded land of the Mukwekma/Ohlone peoples) in this time of terror and hope. Your recent work has given me and all your readers much to think about regarding the limits of “the” (?) human, of black female bodies, of archives, infamy, and vulnerability.

In reorganizing my home office (I have not been to Stanford in many months now), I came across some notes I made for the panel we did at the Cultural Studies Association in 2011 with Francesca Royster and Deb Parades. Do you recall that? The panel was titled after your now second book, Infamous Bodies—and the panel’s subtitle was “the racial lure of transnational bodies.” I think that you presented what became the Mary Seacole chapter! I shared work on Edmonia Lewis (about whom more below). Although you changed the subtitle of your book to “Early Black Women’s Celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights,” I have to say I also loved “the racial lure of transnational bodies.” The word “lure” is a near rhyme with allure and suggests celebrity. So, too, that the idea of “transnational bodies,” as opposed to “early black women’s celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights” helps us to conceptualize these figures as bodies in motion, or to invoke Daphne Brooks’s work, “in dissent.” What do you think about these ideas in retrospect? As it turned out, infamy is the keyword of the title. A third meaning of this term is: “(of a person) deprived of all or some citizens’ rights as a consequence of conviction for a serious crime.” You mention “criminalization” at least four times in the book, imagining this as a horizon of possibility in the post-civil rights imaginary for these vulnerable black female bodies. But how do you understand the criminal aspect here? Also, since vulnerability appears much more throughout the text, did you think about using it in the title? These questions speak to the through line and major arguments in the book.

Before turning to the “inside” of the book, I want to say a word about the para-text or rather, the cover art—Heather Agyepong’s wonderful “Too Many Blackamoors #2” (2015) that you analyze in the penultimate chapter. The cropping of the photograph is perfect and viewers can imagine the image reflected, but not seen, in the elaborate compact the model holds in her right hand. The figure’s gaze is intense: the brow furrowed, the lace collar and ruff of her costume fall into perfect curves while the lighting of the black-and-white image is such that the jacquard silk shimmers “alluringly” and the dark silk curtain appears like framing rays of sunshine setting off the pristine braids held back by black bobby pin and haircap, the single pearl earring serving as a singular reminder of global commodity culture, and of conventions of beauty, luxury, and colonialism. I think this image sets the stage, as it were, for your subsequent analyses.

Speaking generally, this book joins other crucial considerations of black women’s celebrity as it pertains to questions of subjection. I marveled at how this work both diverges and follows from your first book, Difficult Diasporas: The Transnational Feminist Aesthetic of the Black Atlantic. While the former focused on form, highlighting writers, the latter focuses on political figures in multiple discourses. I think that you have written an erudite, wide-ranging study that opens up crucial questions about black women’s subjectivity. I would love to hear more about your decision to include this specific concatenation of actual/historical black female figures—a poet, a concubine, a curiosity, a consoler, and a consort (namely, Phillis Wheatley, Sally Hemings, Sarah Baartman, Mary Seacole, and Sarah Forbes Bonetta). You assert that these figures reverberate in the cultural field, that “in their celebrity, they are archived” (24). Here, I wanted a more trenchant critique of celebrity that might account more for the cautions of “charismatic” figures critiqued by Erica Edwards and Mia Mask. What of these named figures’ singularity? Of their celebrated “two bodies”: the flesh and its infinite signification? I think that you gesture towards the differences here with your attention to contemporary revisions of these subjects. You make clear that aspects of these bodies pose profound questions about “race, rights and difference” (to misquote the title of a famous volume on a related topic)—whether about consent, contracts, concubinage, civic desire, celebrity, or citizenship. Indeed, your work pertains to many major questions that cross temporalities, genres, and nation-states. The sheer scope of this work leads me to ask about the differences among your subjects that are glossed over in the text. For example, does it matter that Hemings is enslaved in America whereas Seacole is a colonial citizen in Great Britain? Also, if infamy and the infamous have legal ties to criminality—what exactly are the crimes of these bodies? Or rather, how do you distinguish between the juridical and ontological or other discursive formations? Is it merely that they have been or could be categorized as black female subjects? In other words, I would love to hear more about your decision to deploy this term in particular. I wondered as well if you think these women are now famous rather than infamous?