Sins & Virtues in American Public Life

9.11.20 |

Symposium Introduction

To paraphrase William Shakespeare: something is rotten in the state of our union.

We see it in our toppled monuments and overcrowded hospitals, feel it in the clouds of tear gas and welts from rubber bullets, hear it in the chants of protest slogans and the shouting at town halls. Yet we struggle to articulate what, exactly, has gone wrong.

The language we typically deploy to name political problems—the system is broken, our government is gridlocked—analogizes society to a massive machine, priming us to seek machine solutions to its dysfunctions. In a machine, if we identify the broken part, the blown fuse, the errant line of code, we can get it up and running good as new. By implication, if we can replace the defective parts of our social machinery—elect the right commander-in-chief, nominate the right Supreme Court justice, redraw gerrymandered districts—we can restore society to functionality. Both political parties have made such changes to great fanfare. Yet as a society we remain as broken and gridlocked as ever. Put simply, the changes aren’t working.

By evoking the breakdown of organic matter, Shakespeare’s language of rot points to an older understanding of society: not as a machine, but as a kind of organism. This biological imagery captures acute social crisis in ways that machine imagery does not. Machines break down and get fixed; organisms get sick, and with the right measures, can heal. But once the organism starts to rot—once the gangrene sets in—drastic measures are required to keep it from dying. Biological imagery clarifies what our moment requires: not another targeted, one-time intervention, but rather, full-scale transformation.

Which is where this symposium comes in. The reflections featured draw on the moral language of sin and virtue to describe contemporary social problems. This language presupposes the ancient image of society as a body politic. Plutarch’s Life of Coriolanus, for instance, describes the senate of the Roman republic as the stomach of the body politic, which digests nutrients and distributes them to the rest of the members.

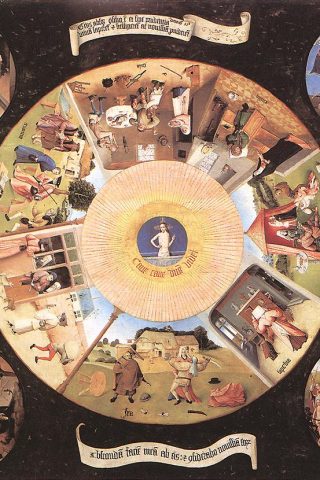

As they faced waves of famine, pandemic, and political unrest, medieval thinkers developed and refined the categories of the Seven Deadly Sins, the Four Cardinal Virtues, and the Three Theological Virtues. In tandem they comprise a kind of toolbox for the care of souls, where the sins diagnose types of spiritual illness and the virtues identify states of spiritual health. This symposium deploys this toolbox to cultivate a comprehensive view of what ails our own body politic and how to nurse it back to health. Each contributor has been tasked with choosing one of the sins or virtues to answer the same basic question: What does sin/virtue x look like in American public life?

We begin with the crisis in our collective body. The forum opens with the Seven Deadly Sins: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride. In medieval thought, they describe how sin damages us both individually and collectively by distorting our pursuit of human goods. As they trace how the deadly sins manifest in contemporary American life, our authors offer a comprehensive diagnosis of the moral state of our body politic.

Once we have diagnosed the illness, we can start to envision what moral health might look like. We begin this reimagining with the Four Cardinal Virtues: prudence, courage, temperance, and justice. They have deep roots in Western philosophical tradition as civic virtues, making them particularly useful for envisioning how individuals can work to promote a functional body politic. As our authors make clear, these virtues can take unexpected, even startling forms in a twenty-first century, late capitalist context.

The symposium concludes with the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love. As the most explicitly relational of the virtues, Christian tradition regards them as essential to human flourishing. They help us imagine what kind of community and society we want to become and embrace the transformations that a thriving body politic requires.

Paul argues that diversity is essential to communal wellbeing: “If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole body were hearing, where would the sense of smell be . . . ? If all were a single member, where would the body be?” (1 Cor 12:17–19). Our contributors come from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives in Christian thought: graduate students, senior scholars, and freelance writers; pastors, musicians, and activists; mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Evangelicals; all drawing from their respective locations of race, gender, and sexual orientation. They deploy centuries-old moral language to diagnose our society’s illnesses and help us envision a flourishing public life. In so doing, they equip us for the vital work of forming a more perfect union.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.03.0078%3Atext%3DCor.↩

Pride and Our Public Life

In memory of George Gatta

1. Preface

I began drafting this article in April 2020 and completed doing so at the end of May 2020. Much has happened between now and then. When I began writing it, the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic were beginning to be felt. I now know that approximately 100,000 Americans have died from the virus and we have reached historic unemployment rates. I completed writing this article as protests and riots have broken out across the United States in response to the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd. I can’t fully comprehend let alone express the gravity of these matters. If there’s something of merit in this article, I hope that it promotes reflection, individually and collectively, about how we Americans are implicated in upholding economic, legal, political, and social institutions that promote justice for some and injustice for others.

Also, I would like to note my use of pronouns. When I use the first-person plural pronouns “we,” “we Americans,” and the like, I admit that I am painting with the broadest brush strokes. Consequently, the picture that emerges won’t be one that everyone fully endorses or even recognizes. Indeed, I have colleagues and friends who actively resist being homologized in this way: whatever political community or common good to which “we Americans” are party neither exists nor is a useful fiction.

2. Pride in the Christian Imagination

What is the sin of pride (superbia)? How does pride take root in and shape our common life? And given its Christian pedigree, how should pride be understood in a pluralistic liberal democracy like the contemporary United States? As the COVID-19 pandemic affects our public health and protests throw our very identity as a nation into flux, these questions are vital to grapple with and urgent to answer.

In the Christian theological imagination, pride is the deadliest of the sins. According to Proverbs, pride leads to disgrace (11:2), strife (13:10), and abomination (16:5). Following Evagrius of Pontus’s index of the sins,

But in our ordinary lives, is pride always so corrupt and morally problematic? To my mind, we should distinguish genuine pride from sinful pride. We take pride in our local communities, e.g., “The fundraiser enabled us to renovate the recreation center.” We take pride in our friends, e.g., “They through-hiked the Pacific Crest Trail.” We take pride in our children, e.g., “She read through all the Harry Potter books on her own.” And we take pride in ourselves, e.g., “Nobody else thought I could do it, but I did. And I’m proud of myself.” In these examples, we recognize and respect some achievement, we take pleasure from and feel satisfaction about what has been accomplished. Moreover, there is a relational quality to these examples: we stand in relation not only to God but also to our community, to our friends, to our children, and to ourselves. And there is perhaps humility in these examples in the very fact that we acknowledge someone’s accomplishment. But it is this very relational quality that leads Lewis to indict pride as the competitive sin. According to him, pride involves comparison, and “comparison is what makes you proud: the pleasure of being above the rest.”

3. Pride in American Public Life

Thus far a brief sketch of the Christian theological understanding of pride. But how does pride find itself instantiated in American public life?

As Americans, we become familiar with pride from an early age. Or perhaps more accurately, we are formed as Americans in pride. The sources for this formation, variously genuine and sinful, include the Preamble (“We the People”) to the US Constitution and Abraham Lincoln’s “First Inaugural Address”; Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Pearl Harbor Speech” and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream”; the Pledge of Allegiance and “The Star Spangled Banner”; Merle Haggard’s “The Fightin’ Side of Me” and Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.”; and airshows featuring fighter jets and T-shirts bearing the slogan “These Colors Don’t Run.” What do these formational displays and messages tell us about what America is and who we are as Americans? I think it’s an admixture (cf. Matt 13:24–30). There is the promise and responsibility of America: justice and equality; liberty and general welfare; harmony and virtue. For America—and we as Americans—are a union,

To be clear, Americans have much to be proud of. But the Christian theological perspective nonetheless cautions us: “Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall” (Prov 16:18; cf. Prov 18:12). In contemporary American public life, how does pride go before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall? I will sketch three examples.

Epistemic Pride. “I know better than you.” On its face, this statement reads comparatively and competitively, paternalizing and infantilizing. But to my mind there are cases when it is descriptively and demonstrably true. For example, the physician who has labored through medical school, residency, and a fellowship knows better than. . . . The glaciologist who has integrated biology, climatology, and geomorphology knows better than. . . . And the art historian who has studied history, language, and theory knows better than. . . . But on talk shows and social media, celebrities use their influence to campaign against childhood vaccinations. To defend their opulent ways of life, talking heads on various cable news channels reject the scientific consensus about climate change. And in college classrooms, undergraduate students beholden to consumerist and emotivist views of knowledge assert that they know as much about a subject as their professors. In all of these examples, we witness prideful challenges to expertise. Despite someone’s lack of training in and dedication to mastering a subject, we find Americans increasingly and publicly claiming that they are experts.

What we witness in these examples, more specifically, is what the political scientist Tom Nichols terms the “death of expertise”: “a Google-fueled, Wikipedia-based, blog-sodden collapse of any division between professionals and laypeople, students and teachers, knowers and wonderers—in other words, between those of any achievement in an area and those with none at all.”

Individualistic Pride. In American lore, there is no figure more mythic and more revered than the self-made man. Rising from disadvantaged circumstances and persevering against the odds, the self-made man exemplifies rugged American individualism. The self-made man pulls himself up by his own bootstraps, drawing on his native reserves of determination and intellect, patience and skill. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, the sociologist Max Weber not only valorized these ideals but also theologized them. On his telling, the individual’s hard work would lead to both proximate reward and eternal salvation.

In our mythologization of and reverence for the self-made man’s individualism, we overlook the fact that we are formed in, interact with, and depend on our communities. “Just as our bodies have many parts and each part has a special function, so it is with Christ’s body. We are many parts of one body, and we all belong to each other” (Rom 12:4–8). In philosophical and religious thought, various thinkers have emphasized the importance of community. For example, feminist political theorists (e.g., Eva Feder Kittay and S. M. Okin) emphasize that we are dependent on and formed in our families.

Exceptionalist pride. From Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America to President George W. Bush’s “Bush Doctrine,” we deem America and Americans as exceptional. Our position as Americans is “quite exceptional,” Tocqueville observes, “and it may be believed that no democratic people will ever be placed in a similar one.” In addition to highlighting our proximity to Europe, Tocqueville notes that (among other things) our “strictly Puritanical origin,” our “exclusively commercial habits,” and our “pursuit of science, literature, and the arts” commends “view[ing] all democratic nations under the example of the American people.”

In many ways, exceptionalist pride shares with the epistemic and the individualistic prideful roots: exalting ourselves over and above others. But the consequences of exceptionalist pride bear much more powerfully not only on Americans individually but also Americans corporately and globally. With regard to ourselves, our exceptionalist pride shields us from evaluating ourselves. We overlook or make excuses for economic, political, and racial inequalities: we are the wealthiest nation in global history but millions live in destitution; we acknowledge the obligations of citizenship but suppress voting rights; and we pledge that we are “one nation under God, with liberty and justice for all” but disproportionately incarcerate and violently police only some. In these examples, what is there about which we should positively evaluate ourselves as exceptional? And while we treat ourselves in these shameful ways, we Americans as a corporate body do worse elsewhere. We have seen wars waged in Iraq and Afghanistan and against terror; we have witnessed democratically elected leaders order drone strikes and speak glowingly about global despots; and we have condoned extrajudicial killing and torture. And in our public life, this exceptionalist pride is damning: because we exalt ourselves as exceptional, we fail to see that we ourselves are sinful and yet we sentence others—oftentimes and increasingly unilaterally—to suffering and death.

4. From Pride to Humility in American Public Life

We are formed as Americans in pride. Through epistemic pride, individualistic pride, and exceptionalist pride, we demonstrate how we’ve been so formed, misconstruing and exalting ourselves. But for every sin there is a correlate virtue. And for pride, that correlate virtue is humility. “If anyone would like to acquire humility,” Lewis notes, “the first step is to realize that one is proud,” for “nothing whatever can be done before it.”

For such a criticism, see, e.g., Michael Baxter, “Dispelling the ‘We’ Fallacy from the Body of Christ: The Task of Catholics in a Time of War,” South Atlantic Quarterly 101.2 (2002) 361–73.↩

Cf. Michael Walzer, Interpretation and Social Criticism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987); Walzer, A Company of Critics: Social Criticism and Political Commitment in the Twentieth Century (New York: Basic, 1988).↩

See Evagrius of Pontus, Talking Back: A Monastic Handbook for Combating Demons, trans. David Brakke (Collegeville: Liturgical, 2009), esp. 159–73.↩

The City of God, trans. William Babcock (Hyde Park: New City, 2014), bk. XIV, ch. 13.↩

Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Allen: Christian Classics / Thomas More, 1981), II–II, q. 162, a. 1, resp.↩

Mere Christianity, in Lewis, Signature Classics (New York: Harper One, 2017), 103, 104–5.↩

Lewis, Mere Christianity, 104.↩

Lewis, Mere Christianity, 105.↩

Cf. James Madison, Federalist No. 10: “The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard against Domestic Faction and Insurrection,” New York Daily Advertiser, November 22, 1787.↩

Nichols, The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 2.↩

See Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Scribner, 1958).↩

See Charles Mathewes and Evan Sandsmark, “Being Rich Wrecks Your Soul: We Used to Know That,” Washington Post, July 28, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/being-rich-wrecks-your-soul-we-used-to-know-that/2017/07/28/7d3e2b90-5ab3-11e7-9fc6-c7ef4bc58d13_story.html.↩

See Eva Feder Kittay, Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency (New York: Routledge, 1999); S. M. Okin, Justice, Gender, & the Family (New York: Basic, 1989).↩

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), 522–23.↩

Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, §185.↩

See Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Harvey Mansfield and Delba Winthrop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).↩

Bush, Decision Points (New York: Broadway, 2010), 397. This is the “idealistic prong” of the fourfold “Freedom Agenda”: President Bush’s self-appellation for the “Bush Doctrine.”↩

In thinking about this version of pride, I have benefited from reading Stanley Hauerwas and Paul Griffiths, “War, Peace & Jean Bethke Elshtain,” First Things 136 (2003) 41–44.↩

Mere Christianity, 108.↩

Many thanks to John Bartholomew, Debbie Brubaker, Jason Heron, Kelly Lytle, Jamie Pitts, and Gordon Warren for helpful comments and conversation. Special thanks to Jeremy Sabella for his comments and for his generous invitation to participate in this conversation.↩

9.15.20 |

Sloth

What we know today as the Seven Deadly Sins originate from the work of Evagrius Ponticus, who in writing essentially a field manual for desert practitioners of monasticism described what he called eight “evil thoughts.” These were names for thoughts, feelings, instincts, or frames of mind that in his experience led eremites off course.

As Evagrius’s ideas were imported into Latin thought, they were sometimes recast. For example, he speaks of acedia, at the same time an existential listlessness and a restless inability to bear down on the work at hand. Gregory the Great later subsumed parts of the idea into what we know now as sloth and despair. You can see why in this lively excerpt from Evagrius’s Praktikos:

First of all, [the demon of acedia] makes it seem that the sun barely moves, if at all, and that the day is fifty hours long. Then he constrains the monk to look constantly out the windows, to walk outside the cell, to gaze carefully at the sun to determine how far it stands from [dinner time], to look now this way and now that to see if perhaps one of the brethren appears from his cell. Then too he instills in the heart of the monk a hatred for the place, a hatred for his very life itself, a hatred for manual labor. He leads him to reflect that charity has departed from among the brethren, that there is no one to give encouragement. Should there be someone at this period who happens to offend him in some way or other, this too the demon uses to contribute further to his hatred. This demon drives him along to desire other sites where he can more easily procure life’s necessities, more readily find work and make a real success of himself. . . . He depicts life stretching out for a long period of time, and brings before the mind’s eye the toil of the ascetic struggle, and as the saying has it, leaves no leaf unturned to induce the monk to forsake his cell and drop out of the fight.

Evagrius calls acedia the “noonday demon,” and it is surely familiar to anyone who has worked a long and unpleasant day. You can hear across sixteen centuries the excuses for not getting the work done (that’s the sloth) and the dogmatic certainty that the work is simply too great for any one person (despair).

Evagrius seems less interested in judging his colleagues for laziness than he does in understanding from his own experience how monks come to throw in the towel too early. It begins, as he says, with simple misperceptions: the day is moving too slowly, the sun is too hot, the work is too hard. Once the distortions of reality are set, the monk’s psyche quickly starts to look for relief from an apparently intolerable situation. From here, as Evagrius notes, all the other evil thoughts arise: gluttony, impurity, avarice, sadness, anger, vainglory, pride. These are all means to the end of escaping the slow, difficult practice of asceticism. We call them the Seven Deadly Sins, but Eight Spiritual Off-Ramps is closer to accurate.

Pope Francis (or at least his ghostwriters) offers a cogent analysis of how acedia manifests in today’s context in his pastoral letter Evangelii Gaudium: laziness is a problem, yes, but so is action taken withoutpreparation or a solid spiritual practice as a foundation, impatience, an unreasonable expectation of success, or losing touch with the people behind the project. His concluding remarks on the subject seem particularly relevant:

Today’s obsession with immediate results makes it hard for pastoral workers to tolerate anything that smacks of disagreement, possible failure, criticism, the cross.

In short, acedia is less about not wanting to do the work to which one has been called as believing the work will take too long or be too hard to accomplish.

That couldn’t be more relevant as I write this, at the end of a series of long nights of unrest sparked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. Chaos agents on the right and left took advantage of the situation to provoke more destruction, and a violent overreaction by police. They didn’t have to push hard to get it: videos quickly surfaced online showing cops brutalizing peaceful demonstrators and bystanders, and tear-gassing, shooting at, or arresting journalists.

The situation has laid bare some of the less pleasant realities of American society. To name just a few: the terrors of racialized policing, law enforcement’s tendency to accelerate conflict with swift and indiscriminate violence when confronted with protestors, their general lack of accountability, sketchy anarchists and white supremacists all too happy to pour gasoline on a fire, and a president who likes to show up in situations like this with a box of matches and a big grin. There is a desperate need for the work of racial reconciliation in the United States that has been held back by political polarization ever since Nixon’s Southern Strategy capitalized on white backlash against the Civil Rights Movement. President Trump needs the chaos and division for his own reelection, but the “fire next time” has been a social problem a long time coming.

In the light of these flames, sadness and despair begin to seem like logical choices, not sins. The work of racial reconciliation is so large, and our own shortcomings so obvious, that we simply cannot imagine it being accomplished. Under the constant assault of racism and violence, it’s little wonder that those without the privilege of escaping it begin to crack, or that those who do have the privilege start to think about when they can lay their work down. It has taken Americans centuries to get to the current boiling point, and it will probably taken centuries yet to fully cool things down. In the meantime, many resent the work to be done, fantasize about fleeing to Canada, Europe, or New Zealand, lose patience with themselves or who they imagine their political enemies to be, or think about shortcuts they could take to achieve a more perfect union. (One of the most damnable of the latter category is the delusion that a class-based political revolution could sweep aside racial divisions. It cannot, and never has.)

The urgency of a summons rarely improves its response rate. That’s no less true when it is a call to difficult, ill-defined work with no end date. And it is certainly no less true when it is work that will challenge the worker’s assumptions, status, and comfort in the world, as racial reconciliation will for most whites. But to heal the divisions of society is to make peace, and for Christians (I will only speak for my own tradition) to make peace is at the very heart of God’s mission. That places it at the heart of Christian mission as well. To be a Christian is to make peace. There is no other way. The work is difficult, and the work is ours.

To get a sense of the scale involved here, consider that real reconciliation requires justice. Wounds cannot be healed while relationship are out of balance. To give a couple of ripped-from-the-headlines examples, police officers must be held accountable for brutality against racial minorities. There’s no way to bring black and brown and white together when whites are literally stepping on the necks of black people. Likewise, provocateurs—the people lighting up American cities for lulz—must also be brought to justice. There’s no room in reconciliation for idiots trying to start a race or class war.

Nor is reconciliation amnesiac. We cannot forget the wrongs and the suffering of the past. This gets complicated, as South Africa discovered with its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Both sides of any given conflict will end up with grievances, real or perceived. It’s important to hear them all out.

Another lesson to be learned from South Africa is that forgiveness is almost inevitably necessary in order to accomplish reconciliation, but it can never be required of victims of injustice. Follow the logic here: there’s no way to repay the debt owed to black citizens for generation after generation of police abuse, much less the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. Certainly more can and should be done! But the debt is staggering, and can never be fully paid. So relationships can never be fully restored until the debts are paid, and the debts are unpayable.

But feeling the burden of those debts maintains the discipline of working toward the restoration of relationship. Whatever else you want to say about reparations, the obligation of them holds white America and its institutions accountable and promotes peace.

It is also true we can never expect those who have been harmed to simply give up their prerogatives, including the prerogative of anger. This is again a matter of justice. Real damage has been done, and sometimes, it can’t be undone. Forgiveness can only be given as a free gift, and it may be a very long wait until conditions are right for it to be given.

So the way out of the mess America finds itself in is not and never can be to simply sweep things under the rug. Things have to change in order for reconciliation to come about, and that change is the work that citizens are meant to be about.

This involves more than showing up at protests and calling people on their microaggressions. Reconciliation on this scale only comes about when political conditions change to make it in the parties’ best interests to make peace. To create that change is very incremental work. Consider the example of Northern Ireland, where a formal process leading up to the Good Friday Accord took four years, and another seven to be firmly cemented into place—but was preceded by talks on and off for twenty years.

The long work in America might be criminal justice reform, which is urgently needed to create the context for racial reconciliation. Change-minded prosecutors need to be elected, city councils and police oversight boards must actually do their jobs, the carceral state needs to be undone on many levels. Again, the point is to change the political calculus, to make it so that it’s more in the interest of elected officials to keep police in check than not to do so. Only then can the work of reconciliation proceed.

None of this can be accomplished without involvement in partisan electoral politics, work that religious liberals are often reluctant to get their hands dirty with. But there are no shortcuts to transformation. The way to build peace across racial divisions in the United States of America in the year of our Lord 2020 is to get better leaders in elected office. That means getting out the vote, funding groups who work to register marginalized people, contributing to candidates who understand the issues, sometimes holding one’s nose and voting for imperfect candidates.

The size and scope of the program of criminal justice reform are epochal. Unless things move very fast, it probably will not be accomplished in the lifetime of many readers. But this is precisely the point. Evagrius and his companions understood their fight to be against forces in place since the fall itself. Evagrius wrote explicitly to help find ways for monks to sustain themselves in a long, grueling, often dehumanizing vocation.

How did they do it? Francis seems to have the right idea in Evangelii Gaudium. One has to be self-giving enough to take on the work, of course. Commitment is mandatory. But commitment must also be rooted in spirituality—not necessarily religious faith, but a sense of purpose and meaning that refreshes wells run dry.

It’s important to start small, with realistic goals. Can police oversight in this community be strengthened? Can an ally be elected to the city council or as a prosecutor? Can law enforcement tactics and training be changed? All of this takes patience. Reforms will not “fall from heaven.” They will be established bit by bit, over an excruciating timeline of refusal, resistance, and sabotage. Far better to go into the work with that expectation and be surprised at how quickly things change than the reverse.

As well, it is important to understand that not every setback is a catastrophe, not every criticism or disagreement is betrayal, and not every sacrifice is unnecessary or bought at too high a price. There will be many ways to reach the goal, many competing projects and agendas. Flexibility is key to continuing the work, as is the understanding that one only plays a role in a greater system.

Most of all, anyone committed to this work has to remain in touch with the people it benefits. That means remembering the names of those lost—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Michael Brown, and too many more to list. Those who suffer from police violence are real people with rich, complicated lives, and deserve to be heard and understood in that light. It also means understanding that the program is not more important than the people who take part in it. The work of racial reconciliation cannot proceed if it’s a game or an academic exercise in revolutionary theory. Those who want to stay in the fight for the long run have to be intimately connected to those directly affected in ways that go beyond protest slogans and performative wokeness. Community, as Peter Block knows, arises from shared struggle, but the reverse is also true: shared struggle can only be maintained with the strength of community and accountability to specific individuals.

Building community to support struggle toward justice can in itself be exhausting and chew up valuable time. But it is far better than the alternative, which is to throw one’s hands up in despair and walk away from the work. And in slowing down to encounter and come alongside community, another truth begins to make itself known: that is the work of reconciliation, and it has already begun.

9.18.20 |

What Does Sloth Look Like in American Public Life?

What does sloth look like in American public life? To answer this question, I will distinguish three possible definitions of sloth, then deploy one of them as a lens that brings into focus a range of current social problems.

In contemporary English, sloth connotes laziness, apathy, and general lack of initiative. Given the prevalence of these tendencies, sloth can seem like a minor moral foible, hardly worthy of the traditional label “deadly sin.” To those schooled in the Protestant work ethic, however, sloth is not a mundane flaw, but a fundamental one. As Max Weber puts it, laziness is “in principle the deadliest of sins . . . because every hour lost is lost to labour for the glory of God.”

This traditional account holds that sloth is not mere laziness, but a rejection of God’s love that regards God’s gracious initiative with sorrow or indifference rather than joy. Thomas Aquinas, for example, views sloth as a vice against the joy of charity that twists character and yields an oppressive “sorrow at spiritual good.”

In my view, this traditional account is preferable to the popular and Weberian varieties as a lens for perceiving the slothful core of a range of problems in American public life that might otherwise escape notice. Just as virtues manifest uniquely in each person, vices like sloth can take a number of forms depending on personality, life circumstances, habits, and social structures. This can be seen in several respects.

First, construing sloth as disordered loving reveals that even apparent opposites, such as laziness and workaholism, are species of the vice. For Aquinas, sloth’s sorrow exposes a general lack of love for God, self, neighbor, and the created order that leaves a void in the human person that prompts a variety of possible behaviors. Some slothful people become lazy, apathetic, and indifferent—after all, being unable to love ensures that nothing is worth doing, pursuing, or valuing. In these respects, sloth divests from agency. Other slothful people become workaholics, chasing after lesser goods rather than resting in God who fully satisfies human desires. To this end, the pursuit of status, the accumulation of possessions, even the constant search for stimulation and distraction, are types of sloth’s disordered loving. For these reasons, the American critique of laziness actually displays sloth’s influence, as this critique has generated an incessant work ethic and economic conditions characterized by anxiety, despair, isolation, and social unrest—the very features that Aquinas and Barth associate with the vice. Examples include the gig economy’s ideal of ceaseless productivity, the increasing number of people needing to work multiple jobs to make ends meet, and the expectation that days off serve the lesser good of recovering strength for working rather than the greater good of enjoying communal fellowship. Thus, lazily divesting from agency and working restlessly are outcomes of sloth’s lack of love.

Second, American isolated individualism is a form of sloth’s “graceless being for ourselves.” Alexis de Tocqueville famously remarked that Americans “owe nothing to anyone, they expect nothing so to speak from anyone; they are always accustomed to consider themselves in isolation, and they readily imagine that their entire destiny is in their hands.”

Third, sloth is a possible factor in the American cultural habits of indifference to the suffering of others and fear of outsiders. Barth says slothful people are like hedgehogs who roll into a ball and threaten the outside world with their spikes.

Fourth, sloth may be at the root of unjust social structures like political partisanship and white supremacy. Writing in the aftermath of World War II, Barth argues that when sloth’s rejection of loving relationship takes root in a society (like it did in Nazi Germany), it directs collective behavior to injustice and violence, and generates social structures that destabilize communities and nations.

Finally, sloth is readily apparent in aspects of the American approach to the COVID-19 pandemic. One important outcome of sloth in Barth’s analysis is “stupidity”—such that we prefer human folly to God’s wisdom.

In conclusion, viewing sloth as a vice against love, rather than as mere laziness, makes it possible to see the variety of forms it currently takes in American public life. On this account, sloth is not just an intrapersonal problem, but an interpersonal one as well. By curving inwards, the slothful person retreats from relationships with God and neighbor, and acts in ways that harm the self, society, even the environment. One benefit of this account is conceptual simplicity, as it becomes possible to see that the range of problems noted above—from workaholism to white supremacy—are species of sloth. Another benefit is clarity concerning how common choices to combat laziness and secure individual liberties may actually create the social conditions under which sloth’s disordered loving takes root. Seeing sloth as a vice against love, therefore, is preferable to the popular and Weberian conceptions as a lens for viewing a range of issues American public life.

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (New York: Routledge Classics, 2001), 104.↩

Aquinas, ST II-II q. 35.↩

Barth, CD IV.2, 458.↩

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. Eduardo Nolla, trans. James T. Schliefer (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012), 884.↩

This argument is developed at length in Christopher D. Jones and Conor Kelly, “Sloth: America’s Ironic Structural Vice,” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics 37.2 (2017) 117–34.↩

CD IV.2, 405.↩

CD IV.2, 420–21, 436–37, 441–43, 468–69, 476–78.↩

CD IV.2: 420–21.↩

CD IV.2, 410.↩

“COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 22, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html.↩

Jonathan Allen et al., “Want a Mask Contract or Some Ventilators? A White House Connection Helps,” NBC News, April 24, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/white-house/political-influence-skews-trump-s-coronavirus-response-n1191236.↩

Molly Hennessy-Fiske, “Sacrifice the Old to Help the Economy? Texas Official’s Remark Prompts Backlash,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-03-24/coronavirus-texas-dan-patrick.↩

9.22.20 |

Wrath

Brett Kavanaugh was angry. He had been on the path to becoming a US Supreme Court justice, and now, instead of talking about his distinguished legal career, the nation was talking about his high school parties. Kavanaugh faced the Senate Judiciary Committee, and he could barely contain himself. Seething with rage, he dismissed the allegations leveled against him by Christine Blasey Ford. He had not committed sexual assault, not against her or anyone. He insisted that he was a champion of women in the legal profession, a paragon of integrity. His face turning red, tears welling in his eyes, Kavanaugh denounced the “last-minute smears” that have “destroyed my family and my good name.”

Ought a judge to become angry? The judicial temperament is composed and collected, carefully weighing the facts and applying the law. For a judge to become so ruffled, something must surely be amiss. Anger tracks wrongs. When we see anger, we know a wrong must have been committed. Normally, we think the appropriate way to respond to such an injury is with words, reasons, and proposals for righting the wrong. Uncontrolled anger is how children respond when they feel themselves wronged—when they do not get what they want. But we can imagine wrongs so grave that an adult, a grown man, a judge, would regress, putting his anger on public display.

This is how anger works: when we see it, we automatically look for the wrong that was committed against the angry man. We realize that the anger could be out of proportion to the wrong, or the wrong could be misperceived, or the anger from one wrong could be displaced onto another. Nevertheless, at root, there is a wrong. Whether or not we join in the anger, we do join in the moral judgment. We empathize with a man wronged. Implicitly, we consider him innocent: the wrong was done to him.

After Christine Blasey Ford’s calm, compelling testimony recounting the attack she suffered as a fifteen-year-old girl, the prospects of Kavanaugh’s confirmation appeared to be fading quickly, with even Republicans beginning to distance themselves from him. Ford appeared so innocent now—and how much more innocent she must have been at fifteen. As soon as Kavanaugh aired his anger, the momentum shifted. Ford’s innocence was recast as confusion; Kavanaugh was now the innocent victim of a political conspiracy that was destroying is career and family.

This is the theater of anger. For his key audience, the white Republican men on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Kavanaugh offered a winning performance. Which is not to denigrate his sincerity, for public anger is always theatrical; that does not diminish its reality. Anger calls on an audience to look for a wrong, and to assess innocence and guilt. Protests succeed more than op-eds and position papers ever can because they cause witnesses to look for a wrong, to look for a guilty party, and to empathize with the innocent. Often protests make this easy: they name the wrong and the wrongdoer on placards.

Here is the standard account of anger: virtuous anger is righteous indignation, an emotion prompted by a wrong and directed against a wrongdoer; vicious anger is wrath, out of proportion to the perceived wrong, feeding on itself so that it grows into a blinding force. Righteous indignation motivates action to right a wrong; wrath motivates action aimed at vengeance, inevitably leading to a cycle of vendetta. If one of anger’s accompanying vices is wrath or irascibility, the other is servility or submissiveness. A disposition to righteous indignation, angering in the right amount in the right circumstances, lies midway between these two vices. For those who are inclined to see Kavanaugh as a virtuous man, or to recognize the virtue of protesters, it must be righteous indignation at play. If the anger on display is great, the wrong at which it is directed surely must be grave.

Virtue describes excellence recognized in a community, and the pillars of a community who do the recognizing are partial to those who look like themselves. Senators recognize Kavanaugh as a virtuous man because he looks like them, talks like them, and went to similar schools as they did. He benefited from the same privileges as they did; like them, he confuses his privilege with “hard work.” So too with the righteous indignation of the working-class white man, as imagined by the media during the 2016 US presidential election: if not exactly the same as elites with respect to their class position, they were clearly recognizable to elites as sharing in virtue. They were elites’ poorer cousins. Their righteous indignation was real and appropriate, even if the way they responded was somewhat confused (as cousins are wont to be).

Women, Black folks, non-Americans: these people cannot share in virtue. Or, only exceptionally, by courtesy: Martin Luther King Jr., cloaked in a performance of respectability, might have virtuous anger, but surely the anger of Malcolm X, Louis Farrakhan, Valerie Solanas, and Fidel Castro is vicious, is wrath. For those dangerously different from elite guardians of virtue, the vice of submissiveness suddenly is portrayed as a virtue. Gandhi’s protest without anger is celebrated, and Nelson Mandela is portrayed as a pacific gentleman deserving reverence (conveniently forgotten is that he was imprisoned for building bombs, and he refused early release conditioned on his renunciation of violence).

Theorists of anger who center the experiences of women, Black folks, and other marginalized groups seek to transform the calculus of virtue. Not by judging better, correcting the distortions of gatekeeping elites. Rather, theorists including Audre Lorde and María Lugones urge us to reconsider anger from the ground up. There may be anger that responds to discrete wrongs, but that is not a particularly interesting species of anger. The type of anger that deserves our attention is anger that cannot be expressed in the language available to us. The language we have is contaminated by systems of domination, such as patriarchy, anti-Blackness, and capitalism. Those systems of domination do wrongs to us in myriad ways, from bodily violence to the dull pains of microaggressions—wrongs compounded because systems of domination take away our ability to name those wrongs properly. All we can do is feel angry, a second-order anger aimed at a whole normative order rather than at a specific wrong.

For theorists of anger from the margins, second-order anger is a source of power. It opens us up to imagining radical transformation, society organized wholly otherwise after our current order is pulled up by the roots. While individuals experiencing second-order anger do not have a language to properly name the wrongs they experience, they are implicitly confident that they do face wrongs. When individuals who experience second-order anger meet each other, they can plot together for the overthrow of the world; they can collectively imagine a radically new world. This is the beginning of genuine organizing: not making explicit a problem shared by a community but rather a community realizing that the problems they share cannot be made explicit until the powers that be are no more.

According to one account of second-order anger, underneath the systems of domination that do violence to us is a world of peace. We naturally connect with each other, sympathize with each other, care for each other. Domination distorts this underlying possibility of right relation, but we can aspire to retrieve it—the voice of anger is that aspiration. Such accounts of underlying peace, sometimes called “relationality” and illustrated with examples from indigenous peoples supposedly untainted by the domination of settler colonialism, turns anger into a sort of sacred practice, a gateway to the world beyond that is already within.

Such an account seems overly optimistic, and this optimism taints its philosophical and theological soundness. What if our world is thoroughly infected by domination, with systems of domination feeding on our individual libido dominandi? What if systems of domination interlock so that even if a particular system of domination can be named and attacked, we can never see a path from our world to a world without domination? What if as soon as we start talking about a world without domination we are caught even more tightly in the net of domination, pulled down into the world rather than lifted beyond it?

If this is the case, then anger goes right when its content is apophatic; anger goes wrong when it fixes on specific worldly objects. Anger goes right when it seems most irrational, when its causes seem most mysterious. Yet second-order anger is not impotent in the world. The person who is angry in this sense is primed for action rather than pushed into action. She knows something is horribly amiss in the world. She knows the options on the table are inadequate responses. When she hears that people are joining together to name domination that infects the world to its bones, she listens; perhaps she joins. She knows organizing will not end her anger. The world will remain fallen. But she also intuits that collective struggle against domination, in its process rather than its end, will provide her with a satisfaction that is inaccessible in the world she inhabits.

Recall this has been a discussion of second-order anger; first-order anger, on such accounts, remains a matter guided by practical wisdom. But theorists of the margins deprive first-order anger of its ultimacy. It is but a crutch for navigating life together in a fallen world. The wrongs it tracks are, at the end of the day, or the world, no more wrong than actions a community agrees are right. Genuine wrongs are the systems of domination that distort our world, the wrongs to which second-order anger responds. Hence, second-order anger trumps first-order anger.

For those suspicious of Brett Kavanaugh’s essential goodness, his performance of righteous indignation should alert us to the need to think beyond the conventional account of virtuous and vicious anger, to the importance of thinking about second-order anger. Beyoncé offers a glorious illustration of second-order anger in her film-album Lemonade. The film is ostensibly organized around a Black woman’s response to suspected infidelity, with section titles signaling an emotional path from “Intuition” to “Denial” to “Anger,” and eventually moving to “Forgiveness,” “Resurrection,” “Hope,” and “Redemption.”

While the lyrics suggest that one instance of infidelity animates the film (the notorious “Becky with the good hair”), the film’s visual universe suggests something quite different. It alternates between images of dancing, emoting Black women, images of buildings and landscapes evocative of the antebellum South, and images of everyday Black life. Anger appears, visually, after Beyoncé has spent an extended time floating underwater, in “Denial.” A voiceover tells of a narrator trying to change herself, to fast, to find religion, to repress feeling. Finally, after a superhuman time submerged, a soaked, sexy Beyoncé emerges into a Black neighborhood, complete with corner store, street vendors, and barbershop. Strutting in a billowy yellow dress, she grabs a baseball bat with the words “hot sauce” written on it from a boy. With an expression on her face shifting quickly between inscrutable, determined, joyous, and enraged, Beyoncé smashes car windows, a fire hydrant, a pinata, a store window, a security camera, and finally the camera filming the video itself. As she smashes, flames erupt on the street behind her.

Visually, Beyoncé’s anger appears to be a one-woman riot. Black stores and cars are smashed, the neighborhood is left in fire. Beyoncé’s face reveals playfulness inextricable from wrath. There is a specific, worldly occasion for her anger—the suspicion of infidelity in the lyrical register. But her anger, visually, is other-worldly, calling for the joyful destruction of the world. In the visual register, Beyoncé’s anger manifests as the threads of racial domination, of anti-Blackness, are tied together: the legacy of slavery, police violence, economic deprivation, the denigration of Black women, and the disastrous response to Hurricane Katrina. What she is unable to speak in words she shows in pictures: the wrong she responds to seems singular, but it is in fact manifold, constitutive of her world.

Alone, subject to racial domination, the only response Beyoncé can muster is ecstatic, crazed anger. However, in the culminating segment of the film, “Formation,” she presents another option. She is still enraged. For a time, she sings atop a police car in hurricane-flooded New Orleans. But now, “I got hot sauce [her baseball bat] in my bag.” She occupies the antebellum plantation that has intermittently served as the film’s backdrop. Most important, she is organized. She sings and dances in formation with other women (in her Superbowl performance, they wear leathers reminiscent of the Black Panthers). With anger now a tool, priming the work of collective organizing, “I slay,” she sings over and over. She conjures a world where organized Black women cause the police to put their arms up in defeat, a world without domination.

9.25.20 |

Envy

According to Aquinas, “envy is sorrow for another’s goods.” He elaborates on that description by suggesting that envy is an attitude, or perhaps more accurately a passion, experienced by those who share a way of life. For example, he observes that common people do not envy a king nor the king envy common people because they do not imagine they share a world with one another sufficient for them to think they should have what the other has.

Though this seems a commonplace observation by Aquinas I hope to show it is very important for understanding the character of envy. Envy is a vice that threatens the ability to live well, but that vice depends on agreement about goods that can be shared. Interestingly enough, the virtues can be an occasion for envy insofar as one person’s goodness may make someone else envy their way of life.

Aquinas elaborates his understanding of envy as the sorrow at another’s good by providing what might be understood as a phenomenology of envy. For example, he observes with his usual but often overlooked insight about our foibles as human beings, that we may grieve another’s good not because they have it but because we do not have what they have. Accordingly, envy can take the form of a sadness that is occasioned by the good fortune of another. But we are subtle creatures, which means envy can also be the joy we may feel at the misfortune of another.

Aquinas observes that those who love to be honored are particularly subject to envy occasioned by someone who has acquired a reputation for goodness that exceeds their own. The ambitious and the strong are subject to envy, but so are the “faint-hearted.” The faint-heated reckon their lives have been made less by the good fortune of their neighbor.

Aquinas, drawing on Gregory the Great, argues that envy is a capital vice because the vices are so interrelated that one springs from another. Vainglory springs from pride which corrupts the mind because, as Gregory memorably puts it, pride produces envy that “craves for the power of an empty name.” This kind of envy—the envy that is sorrow of another’s spiritual good—is particularly destructive for those that would be Christians. The devil tempts Christians to envy the increase of God’s grace in a brother or sister because such envy is the way death came and comes into the world.

One of the interesting questions raised by Aquinas’s account of envy is whether those possessed by envy can know they are so possessed. Someone may acknowledge that they may envy another’s good fortune, but it is quite another thing to actually believe they are in fact possessed by envy or whether they are prepared to act on such knowledge. Envy may, as most of the vices do, result in self-deception, because we do not want to acknowledge we are envious.

Why that is the case is no doubt a complex matter, but it surely must involve the adequacy of our self-knowledge. In a recent mystery by Anne Perry a character observes that it is “much less painful to hate someone than it is to envy them.”

Envy is often named as a vice in the Bible. Paul usually includes envy in his lists of vices. That envy is so listed can make his account of the significance of envy seem not all that important—i.e., envy is just another sin. But for Paul, envy is not just another sin. Envy is destructive of the kind of people that make the church possible. For Paul, a people and structures must exist that are free of envy if there is to be the kind of community that makes a truth-telling possible. Thus Paul’s admonition in Galatians 5:26 that Christians should not “become conceited, competing against one another, envying one another” clearly presupposes that in the church, envy is incompatible with being a Christian. I think the reason Paul regards envy in such a negative light is very simple. Envy for Paul is incompatible with the love that makes the church the church. Such a love is patient and kind, which means a people so constituted are not envious, boastful, arrogant, or rude (1 Cor 13:4).

That such a love should constitute the relation between Christians is surely the reason envy has no place in the lives of Christians. Envy sows the seeds of conflict. It is not surprising, therefore, that Aquinas treats discord after envy in the Summa. Envy is destructive of community because it has the power to divide people from one another by belittling the life of the other.

The disruption of communal life associated with envy is confirmed throughout Scripture. For example, in the book of James envy is condemned as antithetical to the wisdom that should characterize the life of the Christian and the community that is the church. According to James, where there is envy and selfish ambition there will be disorder and wickedness of every kind (Jas 3:15–16). So envy, as Aquinas suggests, is a vice that cannot help but make the kind of community that the church should be impossible.

As I noted above, the significance of envy can be missed because envy so often appears in a list of forms of behavior that are forbidden in the early church. For example, in 1 Peter, which is surely one of the most ecclesial books in the New Testament, those to whom the letter is written are admonished to rid themselves of all malice, guile, insincerity, envy, and slander (1 Pet 2:1–2). The author of this letter does not develop how these negative characteristics are interconnected, but the list assumes that Christians are different. They are “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people” (1 Pet 2:1).

I call attention to these New Testament passages because they make clear that envy is a vice that is not just destructive for individuals. Paul assumes that envy, which is so often hidden, enables human relations that are destructive. We need friends to help us name and discover that envy possesses us. Therefore, judgments about envy presume a politics for the formation of communities that make the life of those who constitute the church as free of envy as possible. In particular, Paul’s understanding of the variety of gifts necessary for the church to flourish is crucial if envy is to be avoided. That some are wise, some are healers, others the workers of miracles, some have the gift of prophecy, but all manifest the gift of the Spirit is the politics that makes envy incompatible with being Christian (1 Cor 12:4–11).

It is not accidental that Paul claims that each of these gifts—and that they are gifts is extremely important—are a manifestation of the Spirit for the common good. The presumption that there is a good that is in common makes all the difference for how envy is understood as well as morally judged. For if the good is known through the cooperative relations made possible by the virtues, then you can only be glad that your neighbor has a gift that you may not have.

These kind of reflections about the social role envy plays can be contrasted in an interesting way to John Rawls’s discussion of envy in his monumental book A Theory of Justice.

Rawls, therefore, set out to provide a rational basis for an egalitarian understanding of justice that made no use of envy. He sought to develop such an account through a thought experiment he called the original position. In order to create a common understanding of justice, he asked that we each think of ourselves as behind a veil of ignorance in which we know that once the veil was lifted, some would have advantages that others would not. So positioned we could agree on principles of justice by which we could order our lives. The differences that would be present after the lifting of the veil would be based on the difference principle. The difference principle entails that no inequality is justifiable that made the least well-off more disadvantaged.

Rawls did not think his account meant envy was no longer a problem at all, just that it was no longer a problem for the basic structure of our political arrangements. He acknowledged that envy understood psychologically seems endemic to human life. It is so because envy so understood is associated with rivalries that are not subject to rational critique (537). For example, Rawls thinks envy reflects in the envious a lack of self-confidence. But envy so understood is not a threat to the political arrangements Rawls thinks he has defended.

Rawls’s account of envy makes an interesting contrast with Aquinas and the New Testament. In particular, what Rawls does not have in contrast to Aquinas is a good in common that makes envy destructive not only of community but our ability to live lives of virtue. For as I hope I have made clear, envy has been and is understood by Christians to be a vice, and as a vice, envy is a habit that is not only destructive for anyone possessed by it, but also destructive of the politics that is determined by recognition of the gifts of our neighbors.

Envy is a way of seeing the world. Envy tempts us to see difference as a threat or diminishment. Envy is the expression of a view of life that assumes we live in a zero-sum world. The alternative to envy is the reality that those that possess gifts I do not have increase my ability to live a happy life, grateful for how such difference enhances my life. Envy is a belittling vice that robs life of joy.

Yet it is hard to avoid the role of envy in social and economic orders like that of the United States. We are schooled to “get ahead,” though we have little idea what “getting ahead” entails. We are, therefore, tempted to envy those who have gotten rewards we think we should have received. We may not think we envy anyone, but as suggested above, self-knowledge is not necessarily a characteristic of the envious. One can only hope that friends will provide an alternative.

9.29.20 |

Lust, American Style

An Anabaptist Perspective

My assignment is to write on the vice of lust in US-American public life. As an Anabaptist Christian I might be expected to approach this task by naming American ills through a contrast with an idealized vision of the church drawn from Scripture and Anabaptist origins. In doing so, however, I would fail to acknowledge the power of lust within Anabaptism. I would also fail to acknowledge my own Americanness, including the Americanness of my Anabaptism. So instead I will develop an analytic of lust through a discussion of Anabaptist history, and then draw analogies for American public life.

When writing about lust as a theological vice, it is wise to observe Mary Daly’s distinction between “phallic,” patriarchal lust and the “intense longing/craving for the cosmic concrescence that is creation,” which she associates with “Elemental female Lust.”

Daly’s treatment of phallic lust also contains useful distinctions. Describing the patriarchal “Foreground” that dominates day-to-day reality, Daly identifies three types of phallic lust. First, “pure lust” “is characterized by unmitigated malevolence” and manifests as physical and psychological violence against women, including the denial of their “deep purposefulness” (2).

Patriarchal men (and complicit women), however, cannot always bear to face their undiluted lust, and so may flee from it into lust’s second form: “phallic asceticism,” a ritual and ideological attempt to conquer lust by assuming the “femininized” role of passive sufferer of temptation, for example, or violence (36–72). From Daly’s perspective, the ascetic flight from lust only heightens phallicism by intensifying the logic of (destructive) penetration, the denial of the body’s goodness, and the lies that obscure the truth of our patriarchal situation. Lustful illusions can also be perpetuated by a third form of lust, “sublimation,” in which lust is denied by cloaking it in theology—a loving Father God to justify patriarchy, an obedient Mary to affirm rape (72–77).

Against the lust of the Foreground, Daly poses the “Background” possibilities of women’s “Lust,” which she describes in terms of passionate, post-patriarchal pursuit of women’s innate, embodied potential (“happiness”), friendship, and community (chaps. 10–12).

Again, the details of Daly’s proposal should not distract from her helpful categories. Turning them on Anabaptist history, it is possible to see “pure lust” active in the stories of Anabaptist men who have raped and beaten women, such as those recently exposed in a Mennonite colony in Bolivia.

If pure lust is relatively easy to identify, Daly’s descriptions of lustful evasions uncover more occult dimensions of Anabaptist lust. The Anabaptist tradition is deeply invested in its history of martyrdom, and martyrologies have been central to Anabaptist devotional life, especially the 1685 edition of the Martyrs Mirror.

The best-known case of Anabaptist lust is the disgraced theologian John Howard Yoder. In the 1960s or ’70s, Yoder began an “experiment” in which he invited at least one hundred women into various forms of physical intimacy up to and including sexual intercourse.

Notwithstanding the fact that Yoder admitted to exceeding his own boundaries and engaging in intercourse, this case exemplifies the “sublimation” of lust into theology, in this case into an eschatological ecclesiology. The attempt to restrain lust through non-penetrative intimacy also recalls Daly’s description of phallic asceticism,

Yoder may be the most infamous example of Anabaptist lust, but it is important to see that Anabaptism as a tradition has lust deep in its roots. The preface to the 1527 “Schleitheim Confession” document, which served as a basis for unity among some Swiss Anabaptist communities and became important for twentieth-century Anabaptist theological reconstructions, claims unity over and against “false brethren” who “have fallen short of the truth and . . . are given over to the lasciviousness and license of the flesh.”

I have already mentioned the brief episode at Münster, where male leaders forcibly instituted polygamy in order to prepare the New Jerusalem for its returning Lord.

This analysis of Anabaptist lust may seem far removed from American public life. Anabaptism in America, however, should not be viewed as a pristine outlier, but rather as a key constituent of the whole. Many Anabaptists long ago assimilated to American whiteness,

It is therefore unsurprising to witness dynamics identified within Anabaptism as working analogously within the American body politic. At the most general level, Anabaptist and American institutions and leaders have both practiced pure lust—coercing and confining, expropriating and exploiting women and others.

Beyond pure lust, the machinations of phallic asceticism and sublimation are also visible in both Anabaptism and America. Both Anabaptist and American leaders, for example, have repeatedly based their claims to unity and security on the marginalization of women and the celebration of heroic, suffering men.

Anabaptism, moreover, may be at its most American in its tendency to combine distanced exceptionalism and aggressive mission. Anabaptist and American ideologues may have disagreed about the location of the “city on a hill,” but they have agreed that their hard work and sacrifices entitled them to live in it. And they agreed that this gave them the sometimes grim, sometimes gleeful responsibility of spreading their gospels of peace.

Mary Daly wagered that there was an alternative to lust beyond or behind patriarchy. She described this alternative as “Elemental female Lust,” a passion for the possibilities of women in community. A justice-seeking, creation-affirming “intense longing/craving” seems worth wagering on even if, unlike Daly, we hope it can be experienced by more than women and mingle with passion for God. Even if we hope to experience it in Anabaptist and other Christian communities. Even if we hope to experience it in America.

Mary Daly, Pure Lust: Elemental Feminist Philosophy (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1984), 3. The following references to this book are included parenthetically in the text.↩

Jean Friedman-Rudovsky, “The Ghost Rapes of Bolivia,” Vice, December 22, 2013, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/4w7gqj/the-ghost-rapes-of-bolivia-000300-v20n8.↩

See discussion in Traci C. West, “The Gift of Arguing with Mary Daly’s White Feminism,” Journal of Feminist Studies of Religion 28.2 (Fall 2012) 112–17.↩

The list could be extended, of course. With a critical eye to Daly’s argument that transgender people (whom she refers to as “transsexuals”) have bought into a patriarchal lie (Pure Lust, 51–52), violence against trans persons should also be named as a negative form of “lust”—one that Anabaptists have no doubt perpetuated.↩

Thielman J. van Braght, The Bloody Theater; or, Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, trans. Joseph F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1950).↩

Carl Stauffer, “Formative Mennonite Mythmaking in Peacebuilding and Restorative Justice,” in From Suffering to Solidarity: The Historical Seeds of Mennonite Interreligious, Interethnic, and International Peacebuilding, ed. Andrew P. Klager (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2015), 146–47. On the related weaponization of Anabaptist peace theology to silence and marginalize LGBTQ Mennonites, see Stephanie Krehbiel, “Pacifist Battlegrounds: Violence, Community, and the Struggle for LGBTQ Justice in the Mennonite Church USA” (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2015), and Gerald J. Mast, “Pink Menno’s Pauline Rhetoric of Reconciliation,” Pink Menno (August 2, 2013), http://www.pinkmenno.org/2013/08/pink-mennos-pauline-rhetoric-of-reconciliation/.↩

Mennonites have repeatedly moved to lands that have recently been cleared by powerful states (Russia, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Paraguay, etc.) of earlier, usually indigenous inhabitants.↩

Rachel Waltner Goossen, “‘Defanging the Beast’: Mennonite Responses to John Howard Yoder’s Sexual Abuse,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 89.1 (January 2015) 7–80.↩

I assess this rationale in my essay “Anabaptist Re-Vision: On John Howard Yoder’s Misrecognized Sexual Politics,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 89.1 (January 2015) 153–70.↩

It especially recalls her discussion of Gandhi’s similar “experiment” (Pure Lust, 39–41).↩

John Howard Yoder, trans. and ed., The Schleitheim Confession (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1977), 9.↩

See discussion in C. Arnold Snyder and Linda A. Huebert Hecht, eds., Profiles of Anabaptist Women: Sixteenth-Century Reforming Pioneers (Waterloo, ON: Wilfried Laurier University Press), 20–21.↩

See Ralf Klötzer, “The Melchiorites and Münster,” in A Companion to Anabaptism and Spiritualism, 1521–1700, ed. John D. Roth and James M. Stayer (Boston: Brill, 2000), 217–56.↩

Snyder and Huebert Hecht, Profiles of Anabaptist Women, 253–54. Within the “Melchiorite” strain of Anabaptism to which both Menno and the Münsterites belonged, women prophets such as Ursula Jost, Barbara Rebstock, and Anna Jansz had previously exercised considerable influence.↩

Philipp Gollner, “How Mennonites Became White: Religious Activism, Cultural Power, and the City,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 90 (April 2016) 165–93.↩

David Swartz, Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012); Molly Worthen, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).↩

Harold S. Bender, The Anabaptist Vision (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1944).↩

10.2.20 |

Lust, Sex, and the Masquerade of Power

When I say the word “lust,” it’s likely that the next thing that comes to your mind is sex. Not just sex, but lots and lots of sex. Obsessive. Excessive. Or maybe, even illicit kinds of sex. Whatever comes to mind, it’s likely to be some kind of sexual desire or behavior that either pushes the limits or exceeds the boundaries of what is good for us.

Yet, as the well-known idiom “a lust for power” reveals, lust isn’t exclusively concerned with sex. Fundamentally, what lust craves is inordinate control, power, and domination. At its core, lust confuses the difference between power and empowerment. Though both involve our desire to feel personally safe, secure, and self-confident, empowerment, in this context, is about feeling confident that one has autonomy over one’s own life and body. Whereas power gains its confidence by controlling the lives, bodies, and circumstances of others in order to feel more secure.

Because we recognize that lust in this sense is a boundary violation of some kind, it’s reasonable that we would seek to avoid it by clarifying what and where, exactly, those boundaries are. Unfortunately, because sex is so often involved in these boundary violations, we tend to narrowly treat lust as a sexual morality/integrity issue rather than fully recognizing it as a distortion of our desire to secure dignity and empowerment.

As a woman and a gay person, I have special interests in delineating lust (the desire for power) from sexual desire (the want for sex) in light of male domination and heterosexual domination. Both forms of oppression exist because they are able to use sex/sexuality against women and LGBTQ+ people to control, manipulate, and authorize where our bodies “should” be and how our bodies “should” perform in society. The only thing this has to do with sexual morality is the way that the cultural mores regarding sex are used as a justification for maintaining power.

While it is true that undisciplined and obsessive sexual behaviors do cause harm to ourselves and others, it is actually lust which makes sex bad and not the other way around. That is, we should recognize that sex is the target and not the cause of lust. Because lust operates by masquerading as any number of our otherwise natural desires, we need a clear understanding of what, exactly, lust wants, as well as how and where it operates.

Lust constantly intrudes on daily life. Some would point to the proliferation of sexual imagery in modern culture as evidence that society is suffering from an epidemic of lust. Others would argue that our societal obsession with sex goes well beyond mere imagery. From commercial advertising to entertainment and public media headlines filled with the private shame and scandal—there’s little doubt, we’re very entertained, interested in, and influenced by sex. But is this lust? Does the high visibility of human sexuality in our culture suffice as evidence of moral depravity? Or, is this proliferation a reflection of just how genuinely significant and meaningful sex is to us?

One of the reasons why lust favors our sexuality as a target is because sex is inexorably embedded in a web of primal needs. We need healthy, beneficial, and intimate relationships for good psychological health. It is good for us to love and be loved. For a well-balanced life, we need a degree of material security and self-confidence.

But lust is im-balanced. It throws desires off-kilter, either by pushing us to exceed the limits of desires that we try to meet or by overwhelming us with the desires we try to ignore. In a sense, lust is like a tapeworm. It feeds off our desires (whatever they may be), using them as fuel in order to perpetuate itself. It has a way of convincing us that any measure of what we have is unsatisfactory, insufficient, and that we will never be fully secure or happy unless we dominate, possess, and control whatever it is we think we lack. The lie that lust would tell regarding our otherwise natural desires for sex, material goods or self-esteem, is that we will never be secure until we have gained all there is to gain or until we become convinced that we have total command of our domain.

Power over Bodies

Sexual abuse and violence are among the most extreme ways in which power can dominate bodies, particularly female bodies. A staggering one in three women and girls experience sexual violence in their lifetime.

Naming, exposing, and combating sexual harassment and abuse is at the heart of the #MeToo movement. Predominantly, the movement has coalesced around concerns for the victimization of women by men in power, but in broader scope, it has become “viral” because it speaks to the ways in which women, specifically, have had to deal with lust in their daily public lives.

The sexualized expressions of lust may range from just plain irritating, unwanted sexual attention to the extremes of prosecutable criminal abuse. Yet, the point of the #MeToo movement is that regardless of their severity, all of these things cause harm. What women are saying, and their harrowing experiences confirm, is: it’s abuse of power, not sex, that is the real problem.

Inequality, impunity, and shame all contribute to the sexual vulnerability of women in society, and specifically in the workplace.

Most accounts largely recognize how Weinstein used his powerful status to gain access to and sexually exploit his victims. Simply said, Weinstein used his power to get sex. But lust can also use sex/sexuality to get power. Either way, it’s human sexuality that always occupies the vulnerable position. Yet, from the sex-for-power perspective, we can begin to see why even (non-physical) sexual harassment is so injurious. It is not necessary for the bad actor to attain or even desire sexual gratification to utilize sex/sexuality as an effective tool of coercion and domination. In short, lust weaponizes sex and sexuality to gain power.

The power of weaponized sexuality isn’t limited to the physical domination of human bodies. It also includes expressions of power that damage a person’s sexual reputation for the exclusive purpose of elevating the status of the perpetrator. Some of the ways this is done include false allegations of sexual misconduct, unauthorized public revelations of one’s sexual orientation, or good old-fashioned public shaming for anyone who deviates from the script of accepted sexual norms. The prevailing concern in these instances is less about moving toward some public good or justice and more about gaining dominance or authority by negatively manipulating the perceived sexual reputation of another.

Shame and Control

Sexual reputation holds significant sway in our society. Pressures to this reputation can be applied individually, but they can also be used to marginalize entire groups of people. Just as male domination in society exerts its power over women, heteronormative domination seeks to maintain its power at the expense of LGBTQ+ people in very particular ways.

On a civic level, those who occupy positions of power, from lawmakers down to local law enforcement, have used their power to criminalize LGBTQ+ sexual activity and limit or deny access to rights and privileges. This authorizes and legitimates sex-based discrimination in order to consolidate power and privilege for a heteronormative majority.

On a social level, institutional religion has asserted claims to moral authority by stigmatizing non-heteronormative sex and sexual identity. Sexual reputation (or purity) and submission to religious authority are treated as metrics of individual religious piety. Access to leadership roles, full membership, and participation in certain rites and rituals are strictly enforced on the basis of sexual purity, gender conformity, and sexual orientation. (It is also worth noting that these are the same religious means by which women are manipulated to conform to male submission and authority.)