Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision

By

3.24.23 |

Symposium Introduction

On March 24, 1980, the sitting archbishop San Salvador, Óscar Romero, was assassinated at the altar in El Salvador. At a funeral mass not long afterward, the great Jesuit theologian Ignacio Ellacuría (himself one the eight people brutally murdered nine years later in 1989 by a group of elite, U.S.-backed Salvadoran soldiers called the Atlácatl Battalion) famously said that “with Monseñor Romero, God passed through El Salvador.” Although Romero was immediately embraced by ordinary people, who discerned him as a Salvadoran Christ and who regarded him as a martyr—often at great risk to themselves—it was not until 2015 when the Catholic Church officially beatified him as a martyr and until 2018 when it canonized him as a saint. He is currently under consideration as a doctor of the church, a designation for those saints whose theological corpus edifies the whole church.

It is a fascinating development, for since Romero’s assassination, scholars, in their efforts to understand this particular passage of God through the world, have tended to focus almost exclusively on Romero’s life (especially his three years as archbishop) rather than his theological corpus. In some ways, this is understandable. Romero assumed the archbishopric at a particularly dramatic time in El Salvador, with a massive rise in killings and disappearances of civilians, attacks upon the church’s visible leadership (like Romero’s friend Rutilio Grande, S.J.), and the country rapidly descending into civil war. Moreover, Romero’s own response was also itself dramatic. In contrast to his more cautious approach prior to becoming archbishop, Romero’s forceful critique of the government, his courageous defense of ordinary Salvadorans, and his leadership in the face of church persecution led many to claim that he had undergone a sudden and powerful conversion, like St. Paul on the Damascus Road.

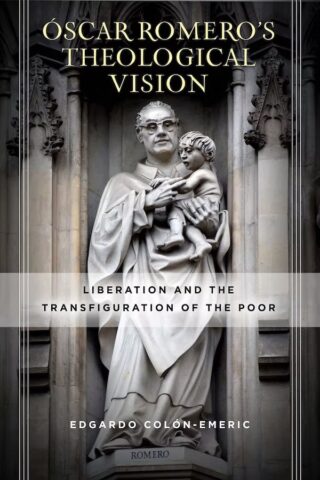

However, Edgardo Colón-Emeric’s award-winning book,

Methodologically, Colón-Emeric’s approach is an exercise in what he calls, echoing Charles Pegúy, ressourcement from the margins. By this phrase, Colón-Emeric means a return to theological sources, but from sites that have traditionally been peripheral to the church’s life (in this case, the land, people, and culture of Romero’s El Salvador) and with different kinds of questions (for instance, poverty and exploitation and the need for liberation) (19). On Colón-Emeric’s account, Romero’s theological vision is a sign of the emergence of Christianity in Latin America from “reflection” church to “source” church, in the language of Henrique de Lima Vaz. In other words, especially in the latter half of the twentieth century, the church in Latin America began to find its own voice and consequently to become a source for others, rather than simply reflect the orientations of Europe or elsewhere, as had been the case in previous centuries.

Helping us engage Colón-Emeric’s exposition of Romero’s theological vision and the generativity of Romero’s thought more generally are six panelists. Carlos X. Colorado begins his response by meditating upon Colón-Emeric’s presentation of Romero’s theology of transfiguration, especially in light of Colorado’s own experience growing upon in El Salvador of the celebration of the feast of the Transfiguration August 5/6th. Colorado also critically engages Colón-Emeric’s treatment of one of Romero’s most celebrated formulations. “If I am killed,” Romero is reported to have said, “I shall resurrect in the Salvadoran people.” Whereas Colón-Emeric argues that these words are not representative of Romero’s larger theological vision and casts doubts on whether he actually said them, Colorado contends the opposite.

In her response, Claudia Rivera Navarrete similarly focuses on Colón-Emeric’s presentation of Romero’s theology of transfiguration and transfiguration as San Salvador’s titular feast, but she questions the purported origins of the feast in Pedro de Alvarado’s victory in 1524 over the indigenous inhabitants of the land now called El Salvador. She also powerfully shows how Romero’s friend and fellow martyr, the Jesuit Rutilio Grande, helped wrest El Salvador’s imagination of transfiguration away from merely a civic celebration and towards one rooted in Christ and the way of discipleship.

Like Rivera Navarrete, Kevin Coleman also reflects on Christianity’s historical complicity in colonial violence, and Coleman’s particular focus is whether Colón-Emeric thinks that Christianity can in fact be decoupled from it. According to Coleman, Colón-Emeric believes it can, while Coleman himself believes it cannot. Coleman offers an extended analysis of Bishop Juan Antonio Dueñas of San Miguel, El Salvador, who in 1936 wrote the pope in order to offer a pontifical decoration of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. Only four years earlier, General Martínez had perpetrated the infamous Matanza (massacre), brutally repressing an indigenous peasant insurrection, a fact that points to the inextricability of Christianity and the afterlives of colonialism.

Elizabeth O’Donnell Gandolfo asks us to consider the lives of countless women in El Salvador and across the Americas and the globe, who suffer the violence of patriarchy. In light of Romero’s thought, she wonders, if the glory of God is the living poor, where is the glory, and what transfiguration is possible? Can the theological vision and pastoral praxis of San Romero help? While offering a critical feminist analysis of Romero’s theological vision, Gandolfo also shows how his theo-logic of transfiguration can actually help resist the institutional violence of patriarchy.

Stephen Long’s response examines Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision as a profound work of what he, in line with the Methodist/Wesleyan tradition, calls “practical divinity,” which Long defines as “theology that issues forth in good and faithful action. … sett[ing] forth the intellectual substance of the Christian faith in terms of everyday forms such as accessible prose, sermons, hymns, and liturgy.” Both Long and Colón-Emeric are fellow-travelers in this tradition, and Long helpfully situates Colón-Emeric’s previous work on Thomas Aquinas and John Wesley (Wesley, Aquinas & Christian Perfection: An Ecumenical Dialogue), as well as Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision, within it.

Finally, Margaret R. Pfeil’s revisits her own scholarly interest in Romero’s theology of transfiguration, which she wrote about in a seminal 2011 Theological Studies article—an article which Cólon-Emeric explicitly engages inÓscar Romero’s Theological Vision. In her response, Pfeil highlights various aspects of this theology as it is exposited by Colón-Emeric, including its deep engagement with scripture, its ecumenical spirit, and its drawing on a wealth of material related to Central American liturgy and liturgical music. But Pfeil also presses important questions related to the conflicts, ecclesial and otherwise, surrounding Romero and his ministry.

The Catholic Press Association awarded it best book in the “Newly Canonized Saints” category in 2019. Colón-Emeric is the Irene and William McCutchen Associate Professor of Reconciliation and Theology, Director of the Center for Reconciliation, and Senior Strategist of the Hispanic House of Studies at Duke Divinity School. His work examines the estuaries where Catholic and Methodist theological streams, as well as North and Latin American ones, converge.↩

4.12.23 |

Christianity’s Role in American Violence

Can Christianity in the Americas be cleaved from the colonial violence that brought it here? Theologian Edgardo Colón-Emeric thinks it can be. “The history of Latin America has been written in blood,” he writes in Oscar Romero’s Theological Vision: Liberation and the Transfiguration of the Poor. “Latin American theologians heard the question of salvation in the voice of blood and responded with a theology of liberation” (25). Liberation theology, we might say, helps Christianity redeem itself.

As a historian and a partial agnostic—that is, as a methodological and epistemic outsider to this symposium—I am convinced that even in Romero, and even in Colón-Emeric’s most sensitive exposition of his thought, faith, and pastoral approach, Christianity cannot be separated from the violence it underwrote from the conquest well into the twentieth century. In what follows, I want to think together with Colón-Emeric about why I believe this is true and whether a decoupling might be possible.

In Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision, Colón-Emeric argues that Romero should be regarded as “a father of the Latin American church” (12). For more than four centuries, the church in Latin America was concerned primarily with transplanting European Christianity into American soil. After World War II, that began to change. With the Bishops’ Conference in Medellín, Gutiérrez’s writings, and Romero’s prophetic ministry, the Latin American church became a source of renewal for Roman Catholic theology. Romero’s pastoral commitments developed as he interpreted “the wellsprings of theology (sacred scripture, the divine liturgy, and the church fathers)” from the margins (19). One key to understanding this process of “ressourcement from the periphery” is found in Romero’s reworking of the second-century Greek bishop Irenaeus of Lyons’s dictum Gloria Dei, vivens homo (“The glory of God is the living human”) (18). In February 1980, Romero issued his last major theological statement in an address to the faculty and administration of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. He concluded by putting a twist on Irenaeus: “The early Christians used to say, Gloria Dei, vivens homo. We can make this concrete by saying, Gloria Dei, vivens pauper” (quoted by Colón-Emeric, 20). “The glory of God is the living poor”: this phrase, Colón-Emeric argues, synthesizes Romero’s theological vision.

Acknowledging the linkage between Christianity and colonial violence, Colón-Emeric writes, “from the beginning, the Church in the Americas had two faces, two voices: the dominant one, represented by soldiers and clerics who justified violence on behalf of evangelization and colonization, and another largely represented by religious who protested these abuses” (34). One face of the church can be seen in the papal bull Inter caetera (1493), which gave the Americas and their Indigenous inhabitants to the Spanish and Portuguese; its other face can be seen in Sublimis Deus (1537), which provided a measure of protection for those “outside the faith of Jesus Christ” (34).

Along similar lines, the author provides a genealogy of the name El Salvador. He notes that according to one early colonial account, which was subsequently accepted by Pope Pius XII, Pedro de Alvarado named the country after defeating the Cuscatlecos in August 1526. Colón-Emeric observes that Romero uncritically accepted Pius XII’s spin: “Romero speaks approvingly of what the pope called ‘the piety of Pedro Alvarado’ without examining the dark side of the conquest” (64). While Romero may have neglected this question, Colón-Emeric argues that his successor, Archbishop José Luis Escobar Alas, has not. In a 2016 pastoral letter, Escobar Alas reflects on “a pedagogy of death” that Alvarado bequeathed to the country he is said to have named (65). Escobar Alas and Colón-Emeric see the connection between what Pius XII called “the burning piety of Pedro Alvarado” and what Bartolomé de las Casas described centuries prior as “all the adultery, violence, and rape that could be laid at his [Alvarado’s] door” (64). But both the current Archbishop of San Salvador and the theologian interpreting his letter stop short of thinking through the centrality of Christianity to this violence. In their accounts, the initial cause is fundamentally racial, with whites (criollos) excluding Indigenous and then mixed-race peoples (ladinos) from participating in economic and political decisions. Yet the very religious and legal terms through which the conquest and colonization of the Americas was carried out were ineluctably Christian.

Although Colón-Emeric acknowledges that Christians were involved in the destruction of Indigenous worlds, he does not grapple with the role that Christianity itself played in justifying this violence. The Christian/heathen, saved/unsaved, white/Black, friend/enemy binaries that drove the conquest continue to include some by excluding others, with the aim of eventually capturing all for salvation. The author largely ignores the imbrication of Christian narratives, doctrine, and institutions with race-based colonial rule and their continuation during the national period. Instead, he puts most of the emphasis on a persecuted church that presumably dedicated most of its American career to denouncing injustice.

While I recognize that Colón-Emeric is clearly on the side of a marginalized countertradition, I worry about—and so I’d like Colón-Emeric to think with me about—the vestiges of colonial logic that still haunt his book and, more consequentially, even this most liberatory strand of Christian thought and practice. For instance, whereas Colón-Emeric follows Romero in reading the Black Christ of Esquipulas as a sign of “how the glory of Christ transfigures colonial history into salvation history” (162), I wonder if it is not precisely by designating Christ as the agent of transfiguration that colonial violence is replicated. To invoke Robert Allen Warrior in his reading of the Exodus stories through Canaanite eyes, “The peasants of Solentiname bring wisdom and experience previously unknown to Christian theology, but I do not see what mechanism guarantees that they—or any other people who seek to be shaped and molded by reading the text—will differentiate the liberating god and the god of conquest.” Christianity always threatens to unmake the worlds of those who worship other gods. Indeed, my point is that it has unmade those worlds. The old theological seeds of Christian violence against non-Christians lie dormant in statements such as “Divinization is always Christocentric” (237). Why isn’t divinization Allahcentric? Or Krishnacentric? Or Ixchelcentric?

One problem that fuels this forgetting is the one-sided notion of persecution that Christianity often assumes. Colón-Emeric writes: “persecution brings together the face of the broken church and the face of the broken Christ” (167). Fathers Alfonso Navarro, Óscar Romero, and Ignacio Ellacuría, along with tens of thousands of lesser-known Salvadorans, were persecuted by their fellow Christians for attempting to make the love of neighbor meaningful in a violently unequal society. But they are the exception that proves the rule. Christians have persecuted non-Christians (and other Christians) from the conquest to the present. Notwithstanding the countertradition from Las Casas to Óscar Romero, Christianity provided the infrastructure of beliefs that were used to construct and maintain violently hierarchical societies, to bless the expropriations of Indigenous and African peoples, and to secure white European domination over human and nonhuman nature. There is, furthermore, a logic to Christianity in which the true Christian is always the victim and never the victimizer (Matt. 5:10). This only enables the faithful in the present to have it both ways, distorting their relationship to their past by claiming as their own the “good” Christians, like Romero, while disavowing the “bad” ones, like Pedro de Alvarado, as conquerors or Christians with a distorted theology. I worry about such distortions and disavowals, because they blind Christians to their past, to their present, and thus to themselves.

~

One example will suffice.

On June 12, 1936, Bishop Juan Antonio Dueñas of San Miguel wrote a letter to the Vatican’s secretary of state, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, for the express purpose of requesting that the Vatican confer a pontifical decoration on the “Most Excellent Mr. President General Sir Maximiliano Hernández Martínez.” Just four years prior, General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez had overseen the execution of thousands of people in central and western El Salvador.

In the early 1930s, rural workers had a long list of grievances. They could remember a time of prosperity, and they knew when they had lost their land to an expanding coffee elite. As the state repressed the leftist labor movement, militancy increased, setting in motion a dynamic of polarization that ended catastrophically. In January 1932, despite being outmatched, the Salvadoran Communist Party reluctantly launched an insurrection. The insurgents took control of six towns and villages and held them for just a day, killing fewer than twenty civilians in the process, each of whom was a political target. In response, General Hernández Martínez’s military regime killed around 10,000 people.

After the 1932 massacre, Bishop Dueñas lamented the hardships that rural workers faced, but he blamed the Communist Party for bringing “murder, fire, assault and plunder” to a country that only “a week earlier was a flowery and fragrant flower.” According to Dueñas, the problem was not the violent expropriation of subsistence farmers or low wages, but “de-Christianization.” Secular schools, civil marriage, and propaganda from communists and Protestants: these were the purported causes of social unrest. In response, Dueñas encouraged the formation of “catechistic study circles.” In a time of “anguish and terror,” Dueñas asked his fellow Salvadorans to forgive “our brothers who have been duped by satanic communism.”

By 1934, when Dueñas wrote to the Vatican, the government of Hernández Martínez had reestablished El Salvador’s diplomatic mission to the Holy See. Moreover, Dueñas argued, President General Hernández Martínez had not permitted onerous legislative sanctions against the clergy. In fact, he had sustained and protected their privileges (fueros eclesiásticos), maintained friendly relations with the Episcopate, and looked out for the needs of the parishes. Dueñas went further. Hernández Martínez, he said, “has saved our lives and the property of the clergy and Salvadoran society, repressing and punishing with a fierce hand the ferocious and bloodthirsty aims of revolutionary communism which had sought to raze temples, burn and pillage cities, and take power, as in Russia, of the National Government.” In virtue of this, Bishop Dueñas requested that Pope Pius XI bestow a pontifical decoration on General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez.

Arguing against the claims made by Bishop Dueñas, the pope’s ambassador could not see what rights of the church the government of Hernández Martínez had supported or protected, unless perhaps one wanted to count the fact that his wife showed up at charitable events in parishes in the capital. Recommending against conferring special honors upon the general, the nuncio quoted a personal letter that he had received from the Bishop of Santa Ana: “Communism continues among us and is a volcano that can burst when we least expect it.”

But Bishop Dueñas did not give up. For more than two years, he wrote directly to the Holy See, repeatedly insisting that the Vatican bestow special distinctions on Hernández Martínez. Having been selected by Rome in 1920 to establish diplomatic relations with El Salvador, Dueñas may have felt that his connections to the Vatican were deep enough that he did not have to use the papal nuncio in El Salvador as a go-between. Instead, he addressed himself directly to Cardinal Pacelli (who became Pope Pius XII in 1939). Tired of saying no so many times, the Vatican’s ambassador to El Salvador finally suggested that perhaps “we can give General Hernández Martínez the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Gregory.” The paper trail ends in June 1936, with Bishop Dueñas still petitioning the secretary of state to accord honors to Hernández Martínez.

(When Romero was a young boy in Ciudad Barrios, Dueñas made a pastoral visit. According to local legend, during that visit Dueñas pointed at Romero and said, “A bishop you will be.”)

Rather than ingratiating himself with Martínez Hernández, had Bishop Dueñas denounced the general’s government for killing approximately 10,000 mostly Indigenous peasants in 1932, perhaps the civil war of the 1980s would never have come to pass. We must squarely face the role that Christianity in the Americas has played in upholding unequal social structures. Doing so, it seems to me, raises deep questions about the ways that violence and suffering are accorded meaning within the Christian story of salvation.

~

In thinking about Romero, we must attend to Christianity’s own contribution to the violence that he fell victim to. “The vision of the wounded beauty of Christ makes it possible to read the tragic history of El Salvador as what tradition calls a felix culpa, a happy fault,” concludes Colón-Emeric (249). In making this point, he cites Alex García-Rivera: “Sin is a felix culpa when, in overcoming it, the world is made better than if the sin had not been committed” (249). While Colón-Emeric reads the theology of Irenaeus as a warrant for the defense of human rights and dignity, it can also be a way of blaming the victim. When Christianity disavows its culpability for these crimes, a peculiarly Christian form of historical amnesia abets new forms of exclusion and domination.

4.19.23 |

The Violence of Love and the Glory of God

A Call to Cautious Discernment

In 2013, a young Salvadoran woman with lupus and kidney disease was pregnant with an anencephalic baby—that is, a baby that would surely die of natural causes within hours of birth. The woman, commonly referred to as “Beatriz” for the sake of anonymity, had already suffered ill effects from a previous pregnancy, which had almost taken her life. Her chronic diseases placed her at high risk of dying from this second pregnancy and her first child was by then a toddler, at risk of losing his mother. Beatriz and her doctors petitioned the Salvadoran Supreme Court to allow for termination of the pregnancy due to the high risk of maternal mortality. The Salvadoran press proceeded to place Beatriz at the crux of a sensational and highly polarized religious and cultural debate. She was vilified and disparaged with very little restraint by anti-abortion advocates, and her case was discussed, not with her own personhood or the ambiguities of the situation in mind, but with the dogmatic assurance that her desire to terminate the pregnancy was a grave, even diabolical, moral evil. Beatriz gave birth to the baby, which lived for only a few hours, and she died in 2017 from medical complications after a minor traffic accident. Her death could have been averted had she received proper health care in 2013 and beyond.

In 2016, another young Salvadoran woman, Evelyn Beatriz Hernández Cruz, became pregnant due to repeated rape by a gang member and was then convicted of homicide after an involuntary miscarriage. Three years later, Evelyn was granted a retrial and was acquitted due to lack of evidence. She was released from prison at the age of twenty-one after serving thirty-three months of a thirty-year sentence.

In these two brief anecdotes, we catch just a glimpse of the countless stories of women in El Salvador, in the Americas, and across the globe, whose physical and psychological well-being are threatened, and all too often destroyed, by the institutionalized violence of patriarchal control over women’s bodies. Where is the glory of God at work in their stories? Where is transfiguration taking place in their lives?

In The Theological Vision of Óscar Romero: Liberation and the Transfiguration of the Poor, Edgardo Colón-Emeric proffers a beautifully written constructive theology drawn from the homilies, pastoral letters, diaries, and embodied witness of the martyred Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero. According to Colón-Emeric, the motif of transfiguration is the hermeneutical key for understanding San Romero’s theological commitment to the defense and liberation of his suffering people and the promotion of “God’s glory” at work in “the poor person, fully alive.” In this essay, I would like to pose the question to Colón-Emeric, and through him to San Romero: What does it mean to manifest the glory of God in the face of institutionalized patriarchal violence? Does the violence of love disfigure or transfigure the bodies of women like Beatriz and Evelyn? Does the theological vision and pastoral praxis of San Romero reinforce their plight or can it offer resources for women’s liberation from patriarchal violence and for the manifestation of God’s glory?

For Colón-Emeric, San Romero’s theology radiates from his understanding of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor as an unveiling of the mysterious depths of the human calling to manifest the glory of God that is in them as God’s beloved children. Drawing on Irenaeus of Lyons, San Romero affirms that the glory of God is the human being, fully alive, but he makes the Irenaean proverb more specific and concrete for a world of poverty and oppression: The glory of God is the poor person fully alive. God’s glory is consistent with God’s preferential option for the poor as the recipients and the historical subjects of the liberating project of God’s Reign. In Colón-Emeric’s words, the scandal of the Transfiguration in San Romero’s El Salvador lies herein: “The gloria Dei of Tabor is most luminous in the vivens pauper of El Salvador, and the life and hope for these poor ones and for all humanity is the vision of the God who became poor for their sake” (23). As the transfigured people of God, and the body of Christ in history, the church is called to recognize Christ crucified in the suffering bodies of the poor, to sentirse cuerpo histórico with this suffering body of Christ in history, and to promote the humanity of the crucified poor by entering into solidarity with their concrete efforts for liberation. While San Romero never neglects to remind his people that the ultimate telos of human life is the glory of eternal life with God, he also spends the last three years of his life denouncing the sinful structures that crucify human beings and announcing the historical liberation that God desires for human beings in this world and in this lifetime.

Colón-Emeric points out that San Romero’s ecclesial commitment to sentirse cuerpo histórico inevitably entails persecution and martyrdom because, in Romero’s words, “The truth is always persecuted” (Homilias 1:117, cited on 195). More specifically, commitment to the truth of God’s glory in the embodied life of the poor is costly: “Christians who commit themselves to serving with the poor suffer the fate of the poor, which in El Salvador meant disappearance, torture, and death” (195). For San Romero, poverty and persecution ought to be considered as marks of the church, for when and wherever the church thinks, feels, and acts in solidarity with the crucified body of Christ in the poor, the powerful react to this threat to their power with violence. The original, institutionalized violence of poverty and the repressive violence of the powerful coalesce in a pervasive pedagogy of death. Christians, and the church as a whole, are to respond to this violent pedagogy with “the violence of love.”

Colón-Emeric offers a helpful contextualization and theological analysis of this phrase, which appears just once in all of San Romero’s published writings, but which encapsulates his theology of redemptive violence and has historical and biblical precedent: “We have never preached violence, only the violence of love; the violence that left Christ nailed to the cross, the violence that one does to oneself to overcome one’s selfishness so that there may not be such cruel inequalities among us” (Homilías 2:36, cited on 108). Love’s violence is a “holy aggressiveness” that challenges the world’s cruel pedagogy of death with a pedagogy of life, a pedagogy of God’s glory made manifest in the abundant life of all, especially the poor and oppressed. But the transfiguration of the poor traverses the road from Tabor to Calvary; it follows the way of the cross, demanding a death to selfishness and cruelty in order to participate in the new life of God’s glory, made fully manifest in Christ’s resurrection. Following this logic, Colón-Emeric posits that, in San Romero’s theology of transfiguration, it is paradoxically the martyrs who “are the epitome of the human being fully alive. . . . they see the God who became poor and truly become alive” (29).

What does this theology of transfiguration mean in the situation of women like Beatriz and Evelyn, who are condemned to the prospect of early and unjust death by institutionalized patriarchal violence? San Romero’s theo-logic of transfiguration and martyrdom could be manipulated and employed quite easily in the rhetoric of fundamentalist Catholic and evangelical appeals to the sanctity of life that are behind the absolute ban in El Salvador on women’s access to reproductive care that would terminate the life of an unborn child, even in cases of rape, incest, and/or threat to the life of the mother. Such a ban is not unique to El Salvador and advocacy for a similar criminalization of all forms of abortion has gained momentum in the religious and political landscape of the United States. Indeed, the recent reversal of Roe vs. Wade has further opened the door for states to implement such bans on access to abortion as reproductive care across the country. The theo-logic at work here requires that “woman” manifest the glory of God and promote the fullness human life by accepting the cross of her subordinate situation, however harmful it may be to her physical and psychological integrity. San Romero himself plays into this logic in his own reflections on motherhood as a paradigmatic form of martyrdom, which are quoted by Pope Francis in 2015 general audience: “Indeed, it is in the honest fulfillment of duty and in the silence of daily life that we give our lives to God. We give our lives as does the mother who with no fuss, with the simplicity of motherly martyrdom, gives birth and gives her breast to her children and lovingly cares for them. This is what it means to give one’s life” (May 15, 1977 Homily). San Romero’s theological rhetoric of God’s glory made manifest in self-sacrifice, in giving up one’s life, is dangerous for and potentially violent towards women when it is coupled with this paradigm of maternal martyrdom.

A feminist analysis of San Romero’s theological vision demands extreme caution and careful discernment with regards to the forms of violence that are sinful and to be denounced, on the one hand, and the violence of love that aggressively promotes the fullness of life for all people—including women—living in situations of poverty and oppression. If the transfiguration of the poor requires the sacrifice of the bodies and lives of women like Beatriz and Evelyn, then it is yet another tool of patriarchal violence. However, I posit that following San Romero’s theo-logic of transfiguration can actually contribute to the advancement of women’s liberation from the sexist presumption of women’s moral culpability and the resultant structures of domination and violence imposed on women by (mostly) men.

Without pretending to take any particular position on the abortion debate in general, let’s return to the particular situations of Beatriz and Evelyn as case studies in transfiguration. If we explicitly and concretely include women, especially poor women of color like Beatriz and Evelyn, in the preferential option for the poor that San Romero promoted and embodied as pastor and martyr, then we must affirm that they too are the image of the “pierced one,” that they too have been victimized and oppressed by institutional violence. And San Romero does not ask the victims of violence and injustice to accept their plight without complaint or protest, as the cross that they must bear for the sake of God’s glory. To the contrary, San Romero exhorted his suffering people to take up the cross of resistance to institutionalized violence and oppression, in the interest of promoting life and liberation. Following San Romero’s theo-logic, then, we must ask: What does the fullness of life mean for Beatriz and Evelyn? What might promote their full flourishing as daughters of God? What would allow for them to manifest God’s glory? These are questions for our consideration, but it is neither our place, nor the place of the men who hold power in the institutional church to give a definitive answer to them. That is up to Beatriz and Evelyn themselves, for the fullness of their humanity demands respect for their personal integrity and autonomy as subjects, rather than objects of debate and ridicule. In fact, it is in their resistance to the violence imposed upon them—even in the face of vitriolic dehumanization by their opponents—that we might glimpse the glory of God at work in their stories. It is in fighting for their own right to life that the transfiguration of the poor has taken place here. The glory of God is the poor woman, fully alive.

4.26.23 |

A Profound Work of Practical Divinity

Response to Colon-Emeric’s Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision

Reviewing a work whose central character is not one I have studied in depth makes my task difficult. I lack the competence to evaluate whether or not Romero said, “If they kill me, I will rise again in the people of El Salvador.” José Caldéron Salazar reported this statement in the Mexican paper Excelsior immediately after Romero’s death (262). Colón-Emeric argues that the statement makes little sense coming from Romero given his theological and political writings as well as a lack of evidence beyond Salazar’s claim. I always thought it was an odd claim for Archbishop Romero to make. I am inclined to agree with Colón-Emeric, so I find his argument persuasive. If not, then of Rodolfo Cardenal’s “three dueling versions of Romero: the nationalist, the spiritualist, and the liberationist,” the nationalist might gain prominence (8). I don’t want him to be remembered as such, so I also find Colón-Emeric’s version of Romero as “prophet,” “martyr” and “son and father of a Latin American source-church” more compelling (16-17). Yet my evaluation comes from a limited acquaintance with primary and secondary sources.

Reviewing a theological work with which you are in substantial agreement also makes for a difficult task. Nothing is present in it that could use a critical correction. Its theology is not only substantive but beautiful. My review could end with this counsel to readers: take, read, and inwardly digest this work for your intellectual, spiritual, and moral benefit. However, more needs to be said for a proper review fitting such a lovely work. The more that I can competently say comes from (1) my shared vocation with Colón-Emeric as a Methodist theologian and (2) my familiarity with his work.

Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision is a book about Romero, but it is neither hagiography nor biography; it is a profound work in theology, best understood in terms of “practical divinity.” The genre might be confusing to those outside the Methodist/Wesleyan context, but Colón-Emeric places Romero with John Wesley as an “exemplar” of “practical divinity” (xii). Practical divinity is the term that has come to define Methodist theology. In 1744 Wesley began conferences to instruct lay preachers in theology through a method of question and answer. The three main questions where, “What to teach, How to teach, and What to do.” At the third conference in 1746, the question was posed, “What method would you advise them to?” Wesley advised them to rise at 4 am and “partly to read some Scripture, partly some close practical book of divinity” until 5 am (Outler ed., John Wesley, Oxford, 162). Practical divinity is theology that issues forth in good and faithful action. It produces no metaphysical treatises; it sets forth the intellectual substance of the Christian faith in terms of everyday forms such as accessible prose, sermons, hymns, liturgy.

In his first monograph on Wesley and Thomas Aquinas, Colón-Emeric contrasted Thomas’s “speculative” theology with Wesley’s practical divinity, suggesting that Wesley’s work contributes to Thomas’s doctrine of perfection. Speculative theology ends in contemplation. It makes a way leading to Mount Carmel. Practical divinity benefits from speculative theology, but it has a different purpose. It leads “down the plain to a life of action” (Colón-Emeric, Wesley, Aquinas & Christian Perfection: An Ecumenical Dialogue, 9). Colón-Emeric made a persuasive case for fitting the Wesleyan preaching house within the Catholic cathedral. (Wesley, Aquinas & Christian Perfection, 147).

If his first monograph fits Wesley’s practical divinity within Catholic theology, this second one fits Romero’s theological vision within Wesley’s. One of Wesley’s failed projects was “the Christian Library,” a collection of works in practical divinity that would guide Methodists in “knowledge and vital piety.” It was a well-conceived idea, but Methodist preachers and laity did not spend their mornings reading through the practical divinity of the Christian Library. In one sense, Colón-Emeric’s work takes up that project. Romero offers Methodists, Catholics, and others instruction in practical divinity. He fits within the Christian Library. It is why Colón-Emeric can write, “The more I understood Romero’s theological vision, and sought to live in accordance to it, the more authentically Methodist my witness to Christ became” (xii).

Colón-Emeric’s work begins in the village center of Juayúa in El Salvador, a city where mass executions of indigenous persons took place in 1932. It begins with the history of violence of El Salvador, a theme he frequently revisits showing how Romero did and did not challenge that history. In 2015, Colón-Emeric and his students from the Central American Methodist Course of Study School visited the church in the plaza known as “the Church of the Black Christ.” The Course of Study is Methodism’s alternative seminary for people who lack the resources or sometimes the academic qualifications to attend seminary. It provides training in practical divinity so that they can become preachers. Colón-Emeric is one of the leaders of this alternative seminary in Latin America. He introduces students to practical divinity by not only having them examine texts but also places like Juayúa and images like the Black Christ. The original pale colored wood of the sixteenth century crucifix hanging above the altar in the church in Juayúa darkened over the years. Jesus has been transfigured by the smoke of prayer candles until he resembles more the indigenous who were killed than the Europeans who used the image for colonizing purposes. The peoples’ “piety,” Colón-Emeric states, “decolonialized Jesus” (xi). This image is a central metaphor for Romero’s theological vision. Romero’s work is about the scandal of transfiguration. Like the Black Christ, the prayers of the faithful transfigured Romero, but also the church in El Salvador and in Latin America. It went from being a “reflection” church that depended on European sources to a “source” church that made its own contributions, especially through four strands of liberation theology: a “liberating praxis” that is (1) “focused on the pastoral praxis of the church,” (2) “done from the praxis of revolutionary groups,” (3) “works from historical praxis,” and (4) works “from a historical-cultural perspective” (16-17). As “son and father of a Latin American source-church,” Romero is heir to all these streams.

These are not the only streams Romero inherited. He also inherits an Irenaen vision, albeit a transfigured one. Colón-Emeric sees resonances between Romero’s theology and Hans Urs von Balthasar’s. For those of us who have followed his work, this comes as no surprise. In 2005, he wrote a lengthy piece for the Christian Century entitled, “Symphonic Truth: Von Balthasar and Christian Humanism.” It introduced readers to the vast corpus of Balthasar’s work and suggested that a proper place to begin to study it is not with Balthasar’s large trilogy but with the Christian humanism present in his Truth is Symphonic. That brief essay offers a substantive introduction to Balthasar; it could also be read as introducing Colón-Emeric’s subsequent research agenda. He wrote:

Truth is symphonic–so play your own part. Expand von Balthasar’s bibliography: Read Toni Morrison and Isabel Allende. Attend a staging of Evita. Listen to Duke Ellington. But be forewarned, von Balthasar would say: these intellectual traditions and forms need to stretch and grow in order to make room for Christianity (The Christian Century, vol. 122, no. 11, p. 35).

Colón-Emeric’s work on Romero expands Balthasar’s theological aesthetics, stretching Christian humanism in new directions. Balthasar edited a well-known work on Irenaeus entitled The Scandal of the Incarnation in which he was one of the first to bring forth Irenaeus’s Christian humanism for contemporary theology by elaborating on his phrase, “Gloria dei, vivens homo.” Romero advanced it in the context of El Salvador by adding “Gloria Dei, vivens pauper.” Rather than focusing on the incarnation as Balthasar did, Romero (and Colón-Emeric) focuses on the transfiguration. This permits him to develop a more historical emphasis on transformation. The glory of God becomes associated with the historical transfiguration of the poor. The theme of perfection/divinization present in the Wesley & Aquinas book bears further fruit here as Colón-Emeric draws on a theology of transfiguration, indebted to Romero, to address poverty.

Along with the re-interpretation of Irenaeus and expansion of Balthasar’s theological aesthetics, Colón-Emeric also finds Romero advancing a central Ignatian theme: sentir con la iglesia. He traces this theme through Romero’s letters on the feast of the transfiguration. (190-210). But here too, Romero’s theology does not merely reflect previous sources. The Ignatian theme becomes transfigured: sentirse cuerpo historico (210). To be faithful to the Ignatian sensibility requires “social analysis and spiritual discernment” by being present with the church as it actually exists in its historical embodiment. To feel with the church is expanded. It maintains a central place for Ignatius’ church of Rome, but also includes the church of El Salvador, the ecumenical church, and the church of the poor (210-214).

I have not done justice to the many important doctrinal themes, historical insights, and practical, ethical counsel present in Colón-Emeric’s work. Perhaps I can be excused because I already stated that the way to discover the riches of this work is to read it for yourself. Let me conclude by saying that I’m not inclined to find works on saints, heroes, or extraordinary persons that compelling. We theologians, dogmatic and moral, tend to point in the same direction when we want exemplars: Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Theresa, Óscar Romero, Bonhoeffer and so on. There is a temptation here. Dorothy Day was once reputed to have said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” Robert Ellsberg notes that she did not oppose the role of saints in the Christian life, but she worried that once someone was a saint they were (https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/dont-call-me-saint.) The danger in writing on saints is to make them unlike and far from us, turning them into ideals that show us our failures rather than exemplars that could be imitated. They become a spiritual or political genius; their canonization securing their place in a pantheon of superheroes through whom one prays but not someone who offers practical wisdom for everyday life. Saints appear superhuman. They face death, even martyrdom, with a resolute calmness. They never seem to struggle with prayer, fasting, loving God, their neighbors, or their enemies. They always have the right word at the right time in the right way. The temptation writing on official or unofficial saint is to make them inaccessible, and overlook ordinary, persons. I was once on an elevator with the wife of a well-known theologian whose work had changed my life in considerable ways. I introduced myself and rather foolishly began to explain to her how much her husband’s work had meant for me. She patiently listened and when I finished, looked at me and said, “If I had not cared for our six children, he would not have been able to write a word.” We write books about him, not her. We hold him up as an exemplar and do not know her name. Practical divinity, at its best, should turn our attention to everyday, ordinary persons who live faithfully in the small things.

Colón-Emeric avoids the temptation of turning the blessed Romero into an inaccessible hero. He does not shy away from his failures such as his inability to critique the “piety of Pedro de Alvarado,” the sixteenth century conquistador who gave El Salvador its name and instructed it in a “pedagogy of death.” This blind spot limits, suggest Colón-Emeric, Romero’s ability to confront El Salvador’s history of violence (63-67). He also reminds us that Romero’s martyrdom occurred while he was celebrating a mass for the first anniversary of Sara Meardi de Pinto’s death (266). His martyrdom will be forever linked with her death. Because of him, we also remember her. Because of her, we can remember him. The truth he spoke in public about everyday realities gave voice to the disappeared without that all too common phenomenon of silencing the “subaltern” by claiming to speak for them (49-56). Perhaps this is one of the most important implications of Colón-Emeric’s work for us today: tell the truth. Telling the truth is not necessarily courageous; nor is it superhuman. It is a basic, natural virtue available to all that nonetheless produces strenuous opposition by those who live by deceit. It is a natural possibility that can be perfected by grace. Romero told the truth and it transfigured him and others. This theme runs throughout his life, Colón-Emeric’s book, and is central to any and all transfigurations. The highest praise that can be said of Romero is the praise that ends this book: “Romero of truth.” That is not beyond the reach of any of us.

5.3.23 |

Sentir con la Iglesia

Visiting San Salvador on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Archbishop Óscar Romero’s assassination, I was moved to explore the link between his theological engagement with the Feast of the Transfiguration and the popular liturgical practice, “La Bajada,” through which Salvadorans celebrate it as their patronal feast day. Understanding both its theological and national undertones, Romero used “La Bajada” to connect salvation history with the intense moment in Salvadoran history that his people were living, issuing three of his four pastoral letters on August 6. Eventually, I wrote about Romero’s theology of transfiguration in a 2011 Theological Studies article.

A few years later, reading Edgardo Colón-Emeric’s manuscript for the first time, I felt immense gratitude: He carefully and systematically fleshed out the scriptural and ecclesial streams feeding Romero’s theology, tracing the liturgical sensibilities expressed through his preaching as well as his daily rhythms. As indicated by his episcopal motto, Sentir con la Iglesia, Romero approached every moment from within the life of the church, striving to orient himself as well as the People of God toward Jesus Christ. Colón-Emeric puts it well: “The church to which Romero is inextricably bound is Roman, ecumenical, poor, and Salvadoran” (210).

In this brief reflection on Colón-Emeric’s masterful portrait of Romero’s theological vision, I will highlight just a few of his manifold contributions, namely: Romero’s engagement with ecclesial tradition in a scriptural key, the significance of liturgy and liturgical music in understanding Romero’s theological vision, his ecumenical leanings, and finally, the real cost of Romero’s steadfast commitment to the Roman Catholic Church.

Engaging the Tradition: Gloria enim Dei, vivens pauper

In beautifully evocative prose, Colón-Emeric brings a theologian’s insight and a pastor’s sensibility to bear in contemplatively drawing connections between Romero’s own theological commitments and the context in which he sought to listen to the Holy Spirit’s promptings. This fine attunement to mind and heart is particularly in evidence as Colón-Emeric describes the deeper theological ground of Romero’s well-known adaptation of Irenaeus’ phrase, Gloria enim Dei, vivens homo, to Gloria enim Dei, vivens pauper. Colón-Emeric mystagogically explores Irenaeus’ treatment of the martyrdom of Blandina, a young slave girl whose faithful witness is easily overlooked, like so many of the most marginalized people in El Salvador whose lives signified for Romero Jesus’ presence and the Holy Spirit’s prompting toward loving action for justice. In the beautiful, suffering faces of those treated as expendable, Romero saw the glory of God, the poor person fully alive. In his Louvain Address a few weeks before his assassination, Romero called attention to Salvadorans’ deaths through political repression and oppression as the fruit of structural sin. But, neither for Irenaeus nor for Romero did death have the last word. Blandina’s witness as “exemplar of the vivens homo blazes the way for Romero’s ressourcement of Irenaeus — Gloria Dei, vivens pauper” (258).

This passage is one of many in which Colón-Emeric skillfully depicts Romero’s theological vision by contemplatively engaging the resources of the Christian tradition. The reader emerges with clear insight into the significance of Romero’s identification with Ireneaus’ understanding of the Glory of God made manifest in those deemed least. As Colón-Emeric astutely indicates, Irenaeus and Romero drink from a “scriptural theology of history: ‘God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise’ (1 Cor. 1:27); ‘Power is made perfect in weakness’ (2 Cor. 12:9)” (258).

Romero’s Ecumenical Spirit

Romero once reflected on what he called his own “evolution in pastoral fortitude,” and perhaps a good example is his development of ecumenical sensibilities over time, particularly in light of Vatican II. Colón-Emeric performs a great service in tracing that process, starting with Romero’s account in the early 1950’s of “Orthodoxy and Protestantism as apostasies that have rent the fabric of the church” and his vision of unity as one of the prodigals’ return to the Catholic Church (212). By 1965, Colón-Emeric notes, Romero spoke of the need for conversion by Protestants and Catholics alike, “turning to Christ and growing in holiness” (212). Eventually, Romero befriended Brother Roger of Taizé and during one Sunday homily, he even shared his microphone with Presbyterian pastor Jorge Lara Braud (213).

I find Colón-Emeric’s account of Romero’s ecumenical spirit significant for our own times: What might it mean for more concerted and collaborative ecumenical work in El Salvador through joint practice of the works of mercy and efforts to stem the tide of systemic violence? Among Catholics, at least, this is a question that merits more vigorous attention. I consider Colón-Emeric’s engagement with Romero’s theological vision a great witness to ecumenical and intellectual hospitality, and I could imagine an ecumenical study group using it as a bridge text in discerning possible avenues of collaboration.

Liturgy and Liturgical Music

Colón-Emeric navigates an impressive array of interdisciplinary and archival material, going beyond most of the available literature and synthesizing the arguments of other authors while making clear his own viewpoint. He makes a special contribution in the area of liturgy and liturgical music in the Central American context. Correctly noting that much scholarly work remains to be done here, his fine text is a promising starting point. He carefully traces the Christological thread from the Misas populares of the 1950’s and 60’s through the Misas campesinas of the 70’s to the Misa mesoamericana, holding them in conversation with Romero’s own Christology, at once attuned to the suffering of ordinary people — all people, regardless of their ideology or relationship with the church — and always seen through the pastoral lens of Christ’s presence in, with, and through the church, the People of God (cf. pp. 136 ff.).

Colón-Emeric’s deep Christological exploration helps to situate the significance of various traditional Salvadoran hymns sung in celebration of the Transfiguration each year, enabling the reader to walk the fine line between secular conceptions of patria and sacral commitments to the theological meaning of Jesus’ Transfiguration. Both frame the context for Guillermo Cuéllar’s Gloria, which, as Colón-Emeric notes, is the only Transfiguration hymn referenced by Romero in a homily, that of March 23,1980, the day before his assassination. Gloria ends with these lines: “But the gods of power and money / Are opposed to there being transfiguration. / This is why you, Lord, are the first one / In raising your arm against oppression.”

The Cost of Ecclesial Perseverance

Romero was forced to navigate the treacherous shoals of distorted conceptions of national security defined by the “gods of power and money,” always fixing his gaze on the eschatological horizon of salvation history. For his efforts, he faced backlash not only from political and military leaders, but also from his fellow Salvadoran bishops, some of whom were closely aligned with the right-wing political elite ultimately found responsible for the majority of the estimated 75,000 deaths in the twelve-year Salvadoran civil war, including Romero’s assassination, the murder of the four U.S. churchwomen later that same year, as well as the massacre of the UCA Jesuits and their friends in 1989.

With great and perhaps ecumenically diplomatic understatement, Colón-Emeric observes, “Even in the case of John Paul II, whose interactions with Romero were more difficult, Romero refused to criticize the pontiff” (210). True enough, but more needs to be said: Yes, in spite of intense ecclesial opposition, including from the Vatican, Romero remained staunchly committed to the church and to the Bishop of Rome. I think, though, that further attention to the fraught ecclesial and political dynamics at stake would sharpen Colón-Emeric’s already powerful account of Romero’s theological vision: Romero’s theological and pastoral views were vigorously (and sometimes viciously) contested by members of his own episcopal conference as well as Vatican officials, including John Paul II, and still he persevered, still he dared to hold them as well as himself accountable to the Christological commitments conveyed by his motto, Sentir con la Iglesia. Even after his murder, his ecclesiastical detractors cast suspicion on Romero’s theological and pastoral witness, which in part explains why thirty-eight years elapsed between his martyrdom at the altar (odium fidei) and his canonization.

***

While waiting for Mass to begin as we commemorated the twenty-fifth annivesary of Romero’s assassination in San Salvador, word came of John Paul II’s death. Soon thereafter, a van pulled up near where I was standing on the edge of the crowd, and a radio station reporter emerged. He approached me and asked what I thought about the pope’s death in light of his relationship with Romero. I pictured them meeting joyfully in heaven, I responded. Now they could both know the fullness of God’s love, healing all misunderstandings between them. They both held fast to an eschatological vision of life in God, and now they could enjoy together the face of Christ — luminous, transfigured, crucified, and resurrected. By Christ’s light, they could both advocate for the Salvadoran people. Gloria enim Dei, vivens pauper.

Colón-Emeric’s excellent account of Romero’s theological vision fleshes out the conceptual framework for this prayer of eschatological hope. For this great theological contribution, I extend to him my sincere gratitude.

3.29.23 | Carlos X. Colorado

The Bajada and the Rise of Saint Oscar Romero’s Transfiguration Theology

In sourcing Oscar Romero’s “theology of Transfiguration” to the celebrations of El Salvador’s patronal feast day, Edgardo Colón-Emeric demonstrates the forcefulness you can bring to your argument when you can rest your case on Jesus. Colón-Emeric also brings to bear the keen insights of someone who spent considerable time in San Salvador and understands the texture of its celebrations. In Oscar Romero’s Theological Vision: Liberation and the Transfiguration of the Poor, Colón-Emeric posits that at least some of the tenor of Romero’s theology was shaped and honed by the specifics of the Salvadoran vision of the Transfiguration, which the capital city celebrates in August every year. Colón-Emeric discloses in a foreword that he lived and worked in Romero’s San Salvador. This gives the author added credibility and insight when he suggests that the experience of the Transfiguration Feast processions, and even the physiognomy of the Divine Savior icon used in the commemorations, plays a part in Romero’s conceit of what the transfiguration means for all of us.

I couldn’t agree more. Having grown up in El Salvador, I attended those same celebrations under four archbishops, including Romero, and I can vouch for the vascular nature of the patron saint’s presence, seeping into every corner of the religious psyche of El Salvador. As Colón-Emeric explains, every August 5-6, the Feast of the Transfiguration doubles as a national holiday (see pp. 130-133). The principal religious celebration is a street procession in downtown San Salvador called la Bajada, which Colón-Emeric appropriately translates as “the descent,” but which can also be rendered as “the lowering” or “the taking down.” This refers to the taking down of a religious image (from the altar) and taking to the streets with it to bring religion to the people. This is the “church that goes forth” of Francis’ usage (C.f., Evangelii Gaudium 20-24), and the popular piety which Paul VI said “manifests a thirst for God which only the simple and poor can know” (C.f., Evangelii Nuntiandi 48).

Street processions are an integral part of the “thirst for God” in Central America. The epicenter of Central American processions is the city of Antigua, in Guatemala. Romero knew this city well, having attended bishops’ meetings there, including a watershed retreat in 1972 led by the Argentine Cardinal Eduardo Pironio (a mentor of Pope Francis), and attended by a who’s-who of the Central American episcopate, including the Guatemalan martyr Juan Gerardi, the influential Nicaraguan Miguel Obando y Bravo and the Salvadorans Luis Chavez y Gonzalez and Arturo Rivera Damas. Antigua is known for its massive Holy Week celebrations, characterized by street processions that take over the city and shut down major thoroughfares with colorful flower carpets for the huge floats bearing the Via Crucis images to pass over. In this type of procession, the map of the city is temporarily overridden by a spiritual plan that rebrands the streets’ grid as a City of God.

The Bajada is this type of event. It transfigures the geography of everyday San Salvador unto a divine vision of the capital. The procession involves three major churches, all at different points of town, and the Divine Savior icon is carried from church to church, with tens of thousands accompanying the march. In fact, some believe that the word Bajada refers to the descent from a church at a higher elevation in San Salvador’s topography, down to the main square. This transit of the Divine Savior is proper to the mystery being elucidated because Jesus’ Transfiguration bridges the human and the divine planes. “Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back,” writes Joseph Campbell, “is the talent of the master.” Colón-Emeric confirms as much, citing no less than Iranaeus, for whom “Christ’s transfiguration is … the manifestation into the world of God’s being, his presence, the ‘face’ which was, under the first covenant, unapproachable to men” (p. 355, under fn. 20 for Ch. 6).

Romero’s magisterium was firmly buttressed in the grand spectacles of popular piety, which reinforced Romero’s theme of Sentir con la Iglesia. The rituals through which Romero’s church took to the streets were coextensive with the historic events in the life of the church that found it on the same streets, be it to march in solidarity with the popular masses or to bury its murdered priests. These real “processions” brought the divine down to the human plane. It is fitting that the opening act of Romero’s ministry, the Misa Unica, was such an exercise. After Fr. Rutilio Grande was assassinated during the first month of Romero’s archbishopric, Romero cancelled all Sunday masses in the archdiocese and celebrated a single, outdoor mass on the steps of the Cathedral before 100,000 faithful gathered in the square in front of the church—the same square where the Bajada takes place. The words Romero spoke that day could be appended to Pope Francis’ clarion call to go out and dialog with an increasingly unbelieving world: “I also welcome those who have no faith in the Mass and are also present here. We know that there are many people here who do not believe in the Mass but are here because they are searching for something that the Church can offer them … The Mass is Christ. Those who do not believe in the Mass, listen at once, what you have found today is Christ.”

What Romero’s faithful found was Christ presented in their midst, offering to transfigure their profane reality for a vision of the divine. This transposability of the ritual with real-life sacrifice and immolation lent great credibility to Romero’s claim of “a church incarnated in the problems of its people.” There is, in Romero’s Sentir, a sense that the church, including the hierarchy, is willing to walk alongside the people. Notably, during the Transfiguration procession, the archbishop and the other high-ranking pastors of the church hit the pavement, alongside the people. Romero’s willingness to accompany his flock was acknowledged in Francis’ canonization homily, when he said that Romero “left the security of the world, even his own safety, in order to give his life according to the Gospel, close to the poor and to his people, with a heart drawn to Jesus and his brothers and sisters.” Francis reiterated it more incisively when he reflected on Romero’s Sentir con la Iglesia before the Central American bishops at World Youth Day in Panama: “Romero showed us that the pastor, in order to seek and discover the Lord, must learn to listen to the heartbeat of his people. He must smell the ‘odor’ of the sheep, the men and women of today, until he is steeped in their joys and hopes, their sorrows and their anxieties, and in so doing ponder the word of God.”

Ultimately, the Bajada lowers God down into the political world. The central spectacle offered to Bajada-goers is the enactment of the transfiguration through a mechanical display on a float bearing the image of Christ. The icon of the Divine Savior is usually vested in red clothes, but, at the climax of the procession when the float reaches the Cathedral, the icon is lowered into the inner part of the float, and therein undergoes a change of clothes, to emerge clad in white garments that signify the light that shone forth from Jesus when he was transfigured. (Mt 17:2.) The display before the transfixed crowds has the feel of a Medieval morality play, and Colón-Emeric informs us that historical references to its nineteenth century iterations refer to it as a “performance” (función), “dramatization” (simulacro), or “unveiling” (descubrimiento)—the latter term is one that persists today (p. 130). These theatrical points of reference help confirm the dramaturgical nature of the Bajada as a teaching tool, but on a political stage.

Because of its national prominence and association with the very name of the country (El Salvador = The Savior, i.e., the Transfigured Lord), Romero saw the Transfiguration as a prime, providential teaching occasion of national import and a God-ordered conduit of salvation. Romero saw this implied in a 1942 message from Pope Pius XII, in which the pontiff wished that God’s blessing would, “descending like the collateral of salvation and peace on you [Salvadorans], who are the key of the arc, spread … to the whole continent,” and to “the whole universe” (emphasis mine). To Romero, the country’s name confirmed its privileged place, because, “more than a name,” it represents, Romero said, the “message which is the summary of [God’s] divine plan to save the world, in His beloved Son.” Colón-Emeric succinctly calls the Transfiguration teachings “the Salvadoran gospel” (p. 71).

The Bajada act convenes the mutual presence of the highest civil and religious authorities and, as Colón-Emeric confirms, Romero “weaves patriotic and biblical themes” into his Transfiguration theology (p. 91). The features of the procession, once again, reinforce these themes: the “unveiling” act usually takes place at Plaza Barrios, the main square abutted by the Cathedral on its northern side, and the National Palace on its western side—the meeting of the religious and the political worlds, and the beating heart of Hispanic society in the New World. The Divine Savior icon is usually borne aloft an earthly orb, into which he descends during the ritual spectacle. Jesus’ garments during the procession are often embroidered with the national seal or he may don a blue-white-blue sash representing the Salvadoran flag. All these elements of the ritual spectacle highlight its political overtones.

Thus, Romero’s preaching calls, in an important measure, for the transfiguration of politics. “This is the hour of political programs for El Salvador,” he observes; “but they are political plans that are worthless unless they attempt to reflect God’s plan.” To Romero, “God’s plan … is made actual in Christ present on the holy mountain, transfigured as the model person.” In his 1978 Transfiguration sermon, Romero preached that Christ’s transfiguration is coextensive to all Christians: “Thus we can say that Christ is the Son of Man and all of Christianity is joined with him, the head of this body.” Colón-Emeric summarizes the fusion of the earthly and the divine by stating that “All Salvadoran Christians belong to the people of El Salvador and to the people of God” (p. 199). In his 1978 sermon, Romero articulated the rules for the transfiguration of politics, which boils down to the submission of politics to the parameters of the faith; Pope Francis cited this lengthy passage of this sermon verbatim to a group of young Latin American Christian leaders:

The Church cannot be identified with any organization, not even with those that call themselves Christian. The Church is not the organization and the organization is not the Church. If Christians have matured in their faith and their political vocation, then concerns of faith cannot be simply identified with a specific political concern. Still less can the Church and the organization be identified as one and the same reality. No one can say that within a certain organization all the Christian demands of the faith will be developed. Not every Christian has a political vocation, and political activism is not the only activity that implies a concern for justice. There are also other ways to translate one’s faith into work for justice and the common good. One cannot insist that the Church or its ecclesial symbols become instruments of political activity. To be a good political activist one need not be a Christian, but Christians involved in political activity have an obligation to profess their faith in Christ and to use methods that are congruent with their faith. If a conflict arises in this area between loyalty to the faith and loyalty to the organization, genuine Christians must choose faith and demonstrate that their struggle for justice is for the justice of God’s kingdom and no other.

Thus, the core of Romero’s “Transfiguration theology” is a form of Sentir con la Iglesia.

* * *

Descending from the heights of Mount Tabor to the minutiae of Romero’s blend of theology and politics, Colón-Emeric is skeptical that Romero uttered one of the most famous phrases attributed to him: “If I am killed I shall arise in the Salvadoran people.” The actual Spanish attributed to Romero is even more audacious: “If I am killed, I shall resurrect in the Salvadoran people.” Noting that the quotation has been called into question by Romero biographer and canonization historian Roberto Morozzo della Rocca, Colón-Emeric casts his lot against the validity of the quotation: “even if this were authentic it would not be representative of his theological vision” (p. 264). The stumbling block for Colón-Emeric and opponents of the quote’s authenticity is that Romero would not equate—or, indeed, reduce—resurrection to a political process.

I wonder, though, if Colón-Emeric would consider whether the quote could misstate the exact formulation, but otherwise approximate something Romero might have said. The fact that Romero wrote in retreat notes he made in late February 1980 that he would leave the meaning of his death up to the Heart of Jesus (p. 264-265) does not necessarily rule out his offering it for the redemption of his people (despite the apparent contradiction), because Romero’s February retreat was called by Romero’s confessor his “prayer in the garden,” his Gethsemane moment, a doubting spell after which Romero gathers the resolve to take fate by the horns. It is a moment of weakness and, by definition, of contradiction.

Thereafter, Romero’s resolve solidifies, and he begins to speak defiantly about the indomitability of his message, even if he is killed. “They can kill me,” he tells ACAN-EFE on February 12, 1980, “but the voice of justice will never be stilled.” Romero’s March 2, 1980 homily, in particular, seems to mark a turning point. Romero commingles theological concepts with his hopes for history: “This Lent, which we observe amid blood and sorrow, ought to foreshadow a transfiguration of our people, a resurrection of our nation,” he declares. He speaks of the afterlife in relation to popular causes: “let us not think that our dead have gone away from us,” he says. “They keep on loving the same causes for which they died. Thus, in El Salvador the power of liberation involves not only those who remain alive, but also all of those whom others have assassinated and who are now more present than ever before in the midst of the people’s movement.” (Emphasis added.) They have risen!

The development from “a resurrection of our nation” and the presence of the dead in the people’s movement to a resurrection in the people, or through the process of their liberation, understood in a Christian context is not a quantum leap from these expressions. Finally, previously unpublished files I have discovered in Romero’s archdiocesan archives establish that Romero and the journalist who reported the interview were in contact. (My analysis of these documents is contained in an article in the Revista Latinoamericana de Teología.) In letters exchanged in 1979, Romero complimented the journalist for the truthfulness of his reporting an earlier interview, and the accuracy with which he transmitted Romero’s words. “I have read your articles,” Romero wrote the journalist on September 24, 1979: “they realistically express the situation in our country, for which I am pleased to thank you for the publication of the truth of what is happening, since you dignify yourself as a journalist and become a communicator who enlightens his readers.” The words appear to bestow a vote of confidence from Romero onto the journalist—whom we would have to disbelieve in order to discount the interview.

I query whether Colón-Emeric can see Romero’s “theological vision” as akin to the beatific vision of St. Stephen (Acts 7:56), whereby Romero could have seen the heavens open as he drew closer to his martyrdom, allowing him to envision his own transfiguration in a sanctified political context, as he stared down the specter of death.

3.29.23 | Edgardo Colón-Emeric

Response to Carlos X. Colorado

My first response is to Carlos Colorado. I am profoundly grateful for his textured testimony to the commemoration of the Feast of the Transfiguration. In my book, I argue how the rituals marking this celebration contributed to the formation and reception of Óscar Romero’s theological vision. It is indeed gratifying to have my argument validated and deepened by someone like Carlos Colorado. I particularly appreciated how his translation of the “la bajada” as “the lowering” or “the taking down” complements my own translation as “the descent.” My translation accentuates the Christ’s mission—his divine kenosis, his walk in the world in weakness and vulnerability. Colorado’s translation accentuates the church’s mission—its divine sending to a hungering, thirsting world. With steady attention to historical and liturgical detail, Colorado enriches my account of the “bajada” and Romero’s gospel of transfiguration. He strengthens the bridges I also saw connecting Romero to Pope Francis and states with greater clarity than I attained that “the Bajada lowers God into the political world.” The transfiguration of Christ lights the way for the transfiguration of the polis.

A good conversation partner is not one who simply affirms and amplifies what one says but who also corrects. Colorado takes issue with my treatment of the saying attributed to Romero: “Si me matan, resucitaré en el pueblo salvadoreño” (or “If they kill me, I shall resurrect in the Salvadoran people”). Colorado rightly notes that I follow the interpretation of Roberto Morozzo della Rocca that questions the historical plausibility of the interview which gave rise to the quote, and that I also question the theological coherence of the quote. I argue that even if it is a true Romero saying, it is not a typical Romero saying and therefore not emblematic of his theological vision.

Colorado offers helpful rejoinders to my argument. First, Colorado defends the credibility of José Calderón Salazar, the reporter for the Mexican newspaper Excelsior who claimed to have interviewed Romero. Colorado’s discovery of letters from Romero to Calderón challenges Morozzo della Rocca’s depiction of the reporter as untrustworthy and opportunistic. To this rectification of the historical record, I can only say, thank you. Second, Colorado argues that there is the possibility that Calderón misquoted Romero’s words but got the spirit of them right. Colorado cites passages of unquestionable Romero provenance where elements of the disputed saying are found (e.g., “they can kill me, but the voice of justice will never be stilled”). Of course, it is certainly possible that Calderón misquoted Romero, but the key issue for me is the theological coherence of this one statement with Romero’s overall theological vision, and in particular with his distinction between the people of God and the people of El Salvador. In an Advent homily from December 9, 1979, Romero presents this distinction in the sharpest of terms:

I want to insist, dear brothers, in a distinction which in our time needs to be made very clear. It is not the same thing to say the people as to say the people of God. What is the difference? The people is everyone who lives in the homeland (patria). All those are the Salvadoran people, including those who do not believe, those who are indifferent. All those, believers and unbelievers, are the people. But when we say the people of God, we intend to speak of the Christian community, among the Salvadorans.

Here and elsewhere, Romero is at pains to stress this distinction, which he sees being elided in theological currents and popular movements that reduce liberation to the immanent realm. Admittedly—and I am grateful to Colorado for pointing out this passage—in his final transfiguration homily, Romero blurs the starkness of the distinction when he says, “This Lent, which we observe amid blood and sorrow, ought to foreshadow a transfiguration of our people, a resurrection of our nation.”

Perhaps, if Calderon’s citation is roughly authentic, the saying simply crystalizes unresolved tensions in Romero’s theological vision, tensions present in his admiration of the piety of Pedro de Alvarado and repudiation of the conquistador’s pedagogy of death. Or perhaps, as Colorado suggests, Romero’s saying arises from receiving a special vision to steady his bajada through the land of the shadow of death, the descrubrimiento of seeing himself rising up in the hoped-for transfiguration of El Salvador. I am very intrigued and interested by this suggestion and its attendant focus on eschatology. I will revisit this theme later, but I turn next to my response to Claudia Marlene Rivera Navarrete.