Occupy Religion

By

10.12.14 |

Symposium Introduction

10.14.14 |

Ecotones and the Arts of Radical Ecclesia and Radical Democracy

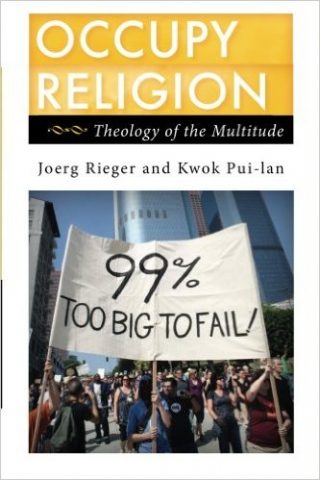

Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude is a timely and important book full of insight and urgency. Inspired by the Occupy movement at a moment that might be a “turning point,” Joerg Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan seek to “challenge traditional ways of thinking about religion and the space that religion is supposed to inhabit.”

Rescuing church from its all-too-frequent alliance with the powerful presiding over hierarchical oppressive orders, they seek to articulate an ecclesia animated by what Jesus is doing in the Gospels. Jesus is on the road, in the gardens, out in the fields, in the streets of the cities; heading to the capital on a donkey, drawing people into critical reflection, organizing in deep solidarity with “the least of these”—the poor, the outcast, the hungry, the gravely ill, the foreigners. The transcendence of God is to be witnessed and practiced in this “indecenting” and will be found nowhere else. For precisely this reason, those who worshipped this God of the anti-Kingdom were thought to be atheists by the Roman hierarchy. However much the hierarchy could tolerate many different God’s—as long as they all conformed to imperial images of omnipotence from on high—the hierarchy simply could not fathom a vision of divinity exemplified by the strange power of a vulnerable being who catalyzed grassroots ecclesia among the lowly, was sometimes convinced to change his mind, avoided and mocked elites, refused to exercise violence, and ultimately allowed himself to be crucified while the Father did not intervene. This made no more sense to those aligned with the “principalities and powers” in ancient Rome, than it does today to many Christians who align with neoliberal power to form what William Connolly has coined the “Evangelical-Capitalist Resonance Machine.”

Throughout Occupy Religion, Rieger and Pui-lan assume a humble posture, asking how the Occupy movement might help rethink church practice and the divine. They embrace “polydoxy,” even as they provocatively affirm the “queerness of God” and congregations that work in and through chaos rather than in control (102). Theirs is a “church without walls”; a “doing church” that is about forming new relationships in the midst of struggles for hospitality, equality, and the urgency of kairos. In place of a hierarchically ordered ecclesia, they explore radically decentered and horizontal practices of church, much like the “neural decentered networks of starfish” that lack a command center (121). Analogous to the Occupy encampments, the church should provide a “moment to experience and live into” the possibility of another world. “It must provide the environment for people to have a foretaste” of the “inbreaking of God’s reign” (123). This requires “rituals that subvert power and disrupt our common sense”: a “habitus of resistance” (127).

* * *

I am largely sympathetic with many of the themes Rieger and Pui-lan advance in this text. In this short space I want to reflect more upon “doing church”—or doing radical democracy—by forming relationships and power that resist, prefigure, and “live into” the possibility of other worlds beyond the horizon of neoliberalism. I wish to think in proximity to their ambition to transform rebellion into a lasting constituent process. Neoliberalism is perhaps the most insidious form of power the earth has seen, so this is no easy task.

While I admire Rieger and Pui-lan’s serious efforts to think and learn in relation to social movements, I nevertheless find it striking that they do not engage the work of interfaith organizations that have been “doing church” in radically democratic and durable ways for several decades, have involved hundreds of thousands of people and countless institutions in dynamic leader-full action, and appear to have significant affinities with many of the authors’ aspirations. Under the umbrella of national and international faith-based organizations such as Gamaliel Foundation, Industrial Areas Foundation, Direct Action and Research Training (DART) Center, and PICO National Network, hundreds of affiliated initiatives in communities across the U.S. as well as in England, Germany, South Africa, and Korea have been bringing together churches, synagogues, mosques, unions, schools, and community centers to cultivate the arts of grassroots democracy, generate interfaith collaboration, build community power, select issues, goals, and strategies, fashion emergent homegrown liberation theologies, and hold political and economic powers accountable.

Because these networks have had significant success at generating widespread, lasting, quotidian democratic practices of horizontal leader-full power, they are among the most promising sites for exploring what it might mean to build a habitus of resistance, fashion prefigurative alternatives, and a practice a theology of the multitude. Yet my concern here is not mainly to point out a gap in the text. Nor is it to suggest that these networks are near-perfect models that the authors and those in Occupy-type movements should simply emulate.

Rather, my purpose is twofold: First, I want to suggest that these movement networks manifest a number of important strengths that powerfully speak to important weaknesses in the Occupy movement, and manifest a number of weaknesses that certain tendencies within Occupy might help address. These different strengths and weaknesses are worthy of serious reflection and transformative work. Indeed, I would suggest that work at these intersections is imperative, if we are to have any chance of dislodging the neoliberal order that is rapidly destroying the planet and all forms of commonwealth. Second, and relatedly, I think that we can grasp the potential fruitfulness of creatively intertwining these different modalities today by paying close attention to how neoliberalism has been so effective at dismantling resistance and alternatives in recent decades—precisely so we can defeat it. At stake is nothing short of how we might form a habitus or resistance that powerfully nurtures radical democracy.

* * *

Rieger and Pui-lan’s text is primarily an effort to provoke reflection toward a theology of the multitude in light of the Occupy movement. Yet, of course, critical considerations of the weaknesses as well as the strengths of this movement are integral to our ability to learn from it, and this becomes easier as the passage of time affords perspectives less captivated by Occupy’s most inspiring moments. Indeed, it is useful to view Occupy as a unique episode in a temporally extended series of rebellious gatherings, from the Battle of Seattle in 1999, to the string of World Social Forums around the world during the first decade of the twenty-first century, to anti-globalization protests, to Arab Spring and the anti-austerity protests in 2011 and beyond. As Rebecca Solnit compellingly shows, rather than seeing these individual uprisings as isolated and short-lived, we should understand them as an emergent-if-discontinuous movement linked through myriad subterranean connections. Such filiations manifest strange capacities for renewal that can bolster our sense of hope.

Yet they also illuminate characteristics that are hauntingly repetitious in highly problematic ways. Todd Gitlin discusses many of these in his inspired sympathetic-yet-critical analysis of Occupy written early in 2012.

These problems are not unique to Occupy, but rather plague many movements of left-wing rebellion, including those mentioned in the previous paragraph (consider Arundhati Roy’s growing frustration with World Social Forum’s inability to articulate common goals, for example). Occupy was a magnificent uprising, its prefigurative politics had important and laudable dimensions, and it brought criticisms of inequality and corporate capitalism into the public sphere in ways that had been suppressed for decades. Yet—beyond all the challenges movements face in the midst of contemporary power and lifeworlds—it got entangled in a predictable set of weaknesses that greatly impeded its power and durability.

The quotidian radical democratic organizing networks mentioned above have managed to address these challenges in ways that (at their best) lodge themselves within and creatively negotiate several sets of tensions, rather than identifying with one side only. For example, they cultivate inquiry, passion, and attachment in relation to visions of “the world as it ought to be,” yet argue that politics is about making connections and transformations in “the world as it is” that require an allegiance to the tension, rather than to purity.

At the same time, these broad-based organizing initiatives too often risk shrinking the transformative character of their horizons of aspiration as they sometimes focus on specific issues in ways that suppress efforts to address larger problems; they can lapse into their own forms of dogmatism, and—wary of the dangers of ignoring the extent to which practices of democracy and ecclesia are crafts—sometimes become overly top-down in ways that suppress new visions, expressions, and modes of action. Equally important, their focus on the quotidian, relational, “meet people where they’re at,” stitch-by-stitch modes of organizing often diminishes their sense of the importance of dramatic uprisings and more protestant politics in a way that makes them blind and deaf to movements like Occupy.

If I were, say, an anti-democratic trickster God, I would infuse the initiatives of those seeking to radically transform contemporary powers with these twin oblivions. The disconnection they create effectively unplugs what most needs to be brought into creative relationship today. Perhaps we can learn something about this from the ways in which neoliberal powers intertwine dramatic “shock doctrine” politics and quotidian micro-powers to repeatedly obliterate resistance and advance capitalist dystopia. As Naomi Klein has poignantly shown, neoliberalism creates, seizes, and employs political, economic, ecological, financial, and military crises in a politics of “shock” that obliterates communities and institutional arrangements that pose resistance to corporatized rule over everything.

In the twenty-first century, global capitalism is perpetually enhancing its power by oscillating between these dramatic and quotidian modes of governance. By means of this systolic-diastolic operation, neoliberalism is intensifying its means of “creative destruction” by many orders of heartless magnitude. To resist this, those who seek to enact other possibilities through radical democracy and radical ecclesia must learn analogous arts of “living in the tensions”: inventing our own creative oscillations between dramatically disruptive “shock democracy” and “shock ecclesia,” on the one hand, and the patient labors of quotidian practice in which we generate alternative flows of receptive bodies, patterns of production, pedagogies, public spaces, and grassroots governance, on the other; interweaving pedagogical practices that proliferate the craft of democracy and ecclesia, and repeatedly opening these to contestation and newness; prefiguring alternatives yet cultivating self-conscious affirmations of the contestability, heterogeneity, messiness, and impurity of all such prefigurations. In these yet-to-be-formed arts lie the alternating currents that just might, against all odds, revivify the body electric of other worlds of possibility.

The monstrous power we face today is no longer the dumb brute, Goliath, whom many social movements, figuring themselves as “David’s,” imagined as their enemy. Rather, we face an unfathomably dynamic and adaptive system. Moreover, because we are significantly engendered by this system, our efforts to form radical ecclesia and radical democracy usually face internally disintegrative and soporific tendencies that are extremely challenging.

More than ever we need to awaken radical democracy and radical ecclesia in ways that make us strange, queer our practices, and enable us do new, powerful, and good works. Occupy, and Rieger and Pui-lan’s meditations in relation to it, make numerous important contributions to this project. I have tried to identify several tensional edges just beyond the horizons of their inquiry that I think we must inhabit if we are to cultivate better forms of relationship and power that the world so desperately needs. Natural ecologists call tensional edges between different ecosystems “ecotones,” a word derived from the Greek oikos (dwelling) and tonos (tension). By carefully tending to the ecotones sketched above, we might teach and learn together how to assemble, occupy, and create dynamic and durable movements from the scattered dry bones rattling in spaces courageously inhabited by those thirsting for something other than the desert that is rapidly advancing across our polities and our planet.

Joerg Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan, Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012). Hereafter cited by page number in text.↩

William Connolly, Capitalism and Christianity, American Style (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).↩

Amidst the vast literature on this type of organizing, see Jeffrey Stout, Blessed are the Organized: Grassroots Democracy in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); Mark Warren, Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Richard Wood, Faith in Action: Religion, Race, and Democratic Organizing in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); and Romand Coles and Stanley Hauerwas, Christianity, Democracy, and the Radical Ordinary: Conversations between a Christian and a Radical Democrat (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2007).↩

Ani DiFranco, “Not so Soft,” Righteous Babe Music, 1995.↩

For Solnit’s developed account prior to Occupy, see Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (New York: Nation Books, 2005).↩

Todd Gitlin, Occupy Nation: The Roots, The Spirit, and The Promise of Occupy Wallstreet (New York: Harper Collins, 2012).↩

Edward Chambers, Roots for Radicals: Organizing for Power, Action, and Justice (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2003).↩

Among the interfaith networks, PICO was by far the most creatively engaged with Occupy Wallstreet. See Laura Grattan, “Populism and the Rebellious Cultures of Democracy,” in Romand Coles, Mark Reinhart, and George Shulman, Radical Future Pasts: Untimely Political Theory (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2014).↩

I also think a second volume would want to engage the question of violence in protest movements.↩

Naomi Klein, Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Picador Press, 2007).↩

I discuss this dynamic extensively in Visionary Pragmatism: Radical and Ecological Democracy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, forthcoming 2015).↩

10.17.14 |

Poetry and Pre-Occupied Religion

Thinking the Theology of the Multitude

The closing sentence of Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude is an open call: “We invite you to participate in developing theology of multitude through concrete reflection and action.”

It is apt to begin with the end in mind.

A Prologue

In the insistent whiplash between scenes of comedy and social commentary on the United States prison industrial complex, the second season of Orange Is The New Black introduces Jimmy, an elderly woman (reminiscent of many a grandmother) incarcerated at the Litchfield prison facility. Though surrounded by a sassy prison family—silvered roots the mark of the “Golden Girls”—their love cannot delay the imminent onset of a withering charge. The incarceration of Jimmy’s body mocks the progressive decline of her mind. She is a woman languishing in the quicksand that is dementia.

Having evaded the distracted eye of her guard-turned-chaperone, our penultimate view of her is in the prison chapel. Thinking her beloved is beckoning her to join him in a pool whose waters only exist in a forgone memory, Jimmy tuck-jumps from the prison’s chapel altar, her absence and injury unnoticed at the foot of the cross. We watch as Jimmy is shuttled away from the prison, broken arm in sling, freed from her prison bars to fend for herself, instead of being given the care she needs, in what is supposedly compassionate release.

The storyline unfolds alongside the debut of Litchfield’s youngest arrival—Brook Soso—an eager caricature of a feisty Occupy-movement millennial (down to the spirit-finger-inspired hand signals). Soso is a passionate, albeit talkative idealist, imprisoned for her recent “political activism, obviously.” While she comes off as a highly dismissible new kid on the block, she is both steadfast and sincere in her efforts. Refusing to succumb to the debasing circumstances, she initiates a prison-wide hunger strike in protest of the treatment of the residents. And the person to whom she makes her most ardent appeal for support is Sister Ingalls.

Though still revered in the prison walls by her ordained title, the former nun is serving her sentence on charges of civil disobedience. The series depicts her as a voice of wisdom, a trove of experience, and the face of the theological to whom many, including Soso, turn for guidance. But Soso has no idea that the Sister has already decried her as “a dirty hippie who has no idea what peaceful protest really means.”

Still, after failing to rouse her comrades with stories of Gandhi and statistics on the efficacy of hunger strikes, Soso makes a final plea to the authority at the table:

“Sister—I thought you of all people would support me.”

But the seasoned veteran’s capacity for resistance is limited to an annoyed eye-roll.

“Oh, honey . . . ” she sighs with piteous condescension. “It’s not Guantanamo.” Like the rest, the Sister trails off before returning to her waffle.

* * *

Despite many attempts—violent and otherwise—to quell her roars, the Occupy movement staked a permanent claim in the American conscious at large. Time Magazine named “The Protester” the 2011 Person of the Year; iconic photos and Guy Fawkes masks are forever branded into word associations of Wall Street; and Saturday Night Live skits qualified the movement via spoof infamy. If Occupy were a reality television star, such ubiquity would be the sign that she had finally made it.

But was Occupy more than a lone starlet looking for fifteen minutes of fame?

The pages of Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude definitively argue otherwise. In good keeping with the horizontal participatory network of the movement itself, Joerg Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan have assembled the careful papier-mâché of social media reports, (re)tweets, articles, advertisements, analyses, and firsthand accounts of increasing economic devastation at the hands of American financial institutions. In a world where the hashtag is the glyph of both gossip and revolution, their offering is a synoptic view of this-thing-called-Occupy, with a deep sense of faith and theological exigency in mind.

For Rieger and Kwok, Occupy is an opportunity for intervention:

[The Occupy movement] opens the door for what we are calling deep solidarity. Whereas solidarity in the past for the middle class has often meant deciding to side with those less fortunate than us, we are beginning to understand that solidarity cuts deeper than this. Rather than trying to understand the condition of those less fortunate in terms of our own, we are beginning to see ourselves in terms of those we have considered less fortunate. Without glossing over the differences, we begin to see their fate as our fate. We are also the 99 percent. (18)

Deep solidarity is the leitmotif at the heart of a Rieger and Kwok’s working theology of the multitude, its “depth” differentiated from a traditional idea of solidarity that imagines Jesus as a modern day CEO, and the Church, and more specifically Christian-identified members of the American middle class (the directly addressed “we” audience of the book), as a hierarchical corporate being of power and privilege (18). Occupy Religion sees deep solidarity as a means to reiterate the interdependence of created beings, and the truth that the flourishing of humanity suffers from the greed and pride that have instantiated the 99/1 binary: “There is a deep concern in our religious traditions for just relationships and the flourishing of all, in particular the ‘least of these’ (Matt 25:45). The religious logic that we will develop in this book tells us that only if they can live well can we all live well, and if they perish, we all perish” (18).

Historically, religious mission and/or evangelism has founded the ideological justification for egregious global offense, eschewing justice and solidarity for personal and political gain. It isn’t so hard, in a world where the power of Jesus Christ can be “crouched in terms of the power of a CEO,” to align tactics of corporate Darwinism, competitive takeover, and wealth accumulation with the will of God (26). But I hesitate at the linguistic impetus for deep solidarity—the idea of being less fortunate—as tied to the latent theological assumption of privilege that fails to connect empathy with empowerment when serving “the least of these.” Although clearly biblical, the colloquial and constant invocation writ large often subtends a pathological gaze toward those understood to be in such a position of need and of lack, skewing one’s subject position further along a spectrum of top-down power.

This is, of course, the very notion that Rieger and Kwok are resisting. And yet I still wonder if the reliance on the familiar reflects yet another way our theological imaginations have been captured by the subtle and easy divisions between us and them, we and they?:

. . . we members of the American middle class have often felt that we were benefitting from the wealth and the power of the 1 percent. Even if we have not consciously reflected on it, we have considered ourselves to be in closer proximity to the ruling class than to the working class. (18)

It seems that a social, theological diagnostic must acknowledge that there is a certain power that comes from the ability to move along a spectrum, from the ability to approximate the 1 percent, even as one now concedes to the falsity of the idea. As Andrea Smith describes, “the undoing of privilege occurs not by individuals confessing their privileges or trying to think themselves into a new subject position, but through the creation of collective structures that dismantle the systems that enable these privileges.”

Even without public consensus on the efficacy or sentiment of Occupy as a form of engagement itself, there is no denying the economic wealth gap of the United States, where political and corporate interest are continually favored at the expense of the welfare of her constituency. As described by economist Joseph Stiglitz,

The top 1 percent have the best houses, the best educations, the best doctors, and the best lifestyles, but there is one thing that money doesn’t seem to have bought: an understanding that their fate is bound up with how the other 99 percent live. Throughout history, this is something that the top 1 percent eventually do learn. Too late.

Although a helpful analytic and a number rooted in reality, the conception of the 99 and the 1 are not without problem. The idea that the one percent have all the “best” reiterates a capitalist logic of scarcity, when the dynamics of access and opportunity are much more complex (and less presumptuous) than wanting what someone else has.

Solidarity now begins with an understanding that we are all in the same boat: we are the 99 percent, and we challenge the 1 percent to stop building their power and wealth at our expense and invite them to join us. (79)

One nation, under subjection to financial tyranny, shaped a new identity that shifted a conversation from the ‘least of these’ to the ‘most of us’ beneath the banner of the 99. But it seems that the concretization of identity, predicated upon the construction of an Other, may be useful for protest but problematic for theology. Is deep solidarity something that can be socially sustained once the numbers change? Is deep solidarity enough to balance the extremes of demonizing those seen as the 1 (or those seen as support the 1, and thus against the 99), or that of flattening the goods of the horizontal network of the 99 into an arid landscape? These are theological questions of futurity, ones that lead me to consider the insight of poetry.

* * *

In the opening pages of Poetics in Relation, Éduoard Glissant widens the aperture of the dark hollow in the “belly of the boat,” the destructive crucible of the slave ship: “Imagine two hundred human beings crammed into a space barely capable of containing a third of them. Imagine vomit, naked flesh, swarming lice, the dead slumped, the dying crouched . . .”

The slave ship is a very specific historical reality, a formative institution wound deeply and theologically in the fabric of the American conscious. It was a vessel that,

“. . . performs translation, displacement, and disordered creation. It embodies a new story of creation, one in which the first family will be reborn as familia oeconomicus. The economic family is not a family structuring its own economic realities, but one being formed by them. The original story is refashioned on the slave ship through the bodies that lay within its holds and the bodies that suffered on deck. The slave ship also captures all other forms of translation: translation of languages, of spaces, of life to death, of innocence to guilt, of joy to unrelenting sorrow.”

“Being in the same boat” is not a particularly unique metaphor to invoke. But when Rieger and Kwok do, such an analogy recalls the theological ways a very literal boat of our past impresses itself upon a theology of the multitude. Today many Americans find themselves economically leveled, confined and constricted in space, the depths of our debt and the destination for the future unknown. A family not structuring its own economic realities, rather in many ways being formed by them. But whereas the slave ships of the Atlantic “distorted the power of joining together many different peoples on a common journey and mission,”

Which is why I find the challenge of relation—of the “multitude-in-relation,” of “God-in-relation” (both terms Rieger and Kwok invoke as chapter subtitles)—though somewhat underscored, to be the most compelling of lessons from Occupy Religion. Relation is the aura of Occupy: the strange amalgamation plastered by the glue of an Arab Spring, soldered by the fireworks that trailed from Barcelona to Athens, molded in a shape neither solid, stable, or sublime. Witness to such relation, then, presses beyond the momentary feeling of solidarity (however deep), to a more substantive vision of sociality. Sociality, a form of life together, “thereby marking a relation whose implications constitute . . . a fundamental theoretical reason not to believe, as it were, in social death.”

And the invocation to see the poetics of relation is something I think Rieger and Kwok already have in mind: “In the midst of this deepening crisis that is becoming increasingly a matter of life and death, theology is not a luxury” (58). Speaking of the urgency of poetry, Audre Lorde writes:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.

Though the authors do not cite Lorde, she is instructive in our thinking, and our rethinking, of a theology of multitude. In choosing to be agents and signs of co-creative change in a world of chaos, theology can form the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams. Toward something more than just survival. Toward our flourishing together. Toward change. Which is to say, “We cry our cry for poetry. Our boats are open, and we sail them for everyone.”

* * *

To quote another participant, “I was told that this should not be a book review,” and these reflections—much like the theology Rieger and Kwok propose, and the movement that they have analyzed—are very much so in medias res. But this is an attempt to think with them, taking seriously the challenge that they present to their reader. What does the Church look like, and what are our conceptions of God? How does Occupy challenge our theologies and our praxis?

If we look back on the opening satirical scene, Sister Ingalls—the face of the Church—looks bothered by the peskiness of the inflated hopes of Soso. But why? Only later do we find that Sister Ingalls’ hesitancy is rooted in her history. She never quite felt she could discern the voice of God. The exhilaration of protest, matched with her growing celebrity, was an addictive coping mechanism: she trespasses for the photo-op, and times her social media attention around her book release. She becomes so unwieldy as to have her vows revoked.

Whether the producers intended it or not, this is a moment for theological reflection. For Sister Ingalls, the solidarity of being imprisoned is not enough to join Brook Soso. She witnesses the same atrocities. She experiences the same suffering. And yet, waffles at breakfast constitute sufficient cause to decline.

These are times of protest, when many are looking to faith, to the Church, for answers and insistence, for understanding and solidarity, for action. When I wrote this during the summer months, I anticipated this would be published near the third anniversary of the encampments in Zucotti Park. Three years later the very language of occupation flies in our faces as we witness senseless death and devastation, from the Gaza Strip to Ferguson, Missouri. We continue to be surrounded by reminders of severe injustice on innumerable levels. And yet we bear witness to the relentless insistence upon resistance, on finding one another, on standing together.

It is the brokenness of Jimmy that reminds Sister Ingalls of who she really is. Despite the risk to her own safety, Sister Ingalls stops consuming food in protest. She fears that she will be alone, as her own pride cut her off from the faith community that once inspired encouragement, support and love. Hospitalized and ready to give up, she is surprised to learn that an entire network of sisters are at the prison gates. They have heard her call. They embody the familiar truth that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In a world where we are constantly reminded of the disposability of bodies, of lives, of futures and of dreams, the writers of Occupy Religion claim that “an unfinished theology serves as a constant reminder that things do not have to be as they are . . .” If Occupy has taught me anything, it is to remember that these words are true. And if considering the theology of the multitude has taught me anything, it is that resistance and struggle are breeding grounds of transformation and hope. Which is to say, in Christian theological terms, that one might actually take seriously the promise “where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them (Matt 18:20).”

Joerg Rieger and Pui-lan Kwok. Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 134.↩

Though it undoubtedly reduces costs of extensive medical care, the stipulations of compassionate release are rooted in an ethical praxis of providing early release for prison residents who are terminally ill or in extenuating circumstances. But the dramatization in the series—clearly unable to care for herself, Jimmy is released back onto the street to fend for herself—disguises the deeper problem of compassionate release, in that it isn’t granted to many who find they need it. For a helpful analysis of the portrayal in the series, see here: http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/06/13/how-oitnb-flubbed-compassionate-release.html. For the actual policy: http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.bop.gov/policy/progstat/5050_049.pdf↩

Though speaking through a lens that focuses on racism and settler colonialism—which brings up its own pertinent critiques of the language of “occupy” (which are beyond the scope of direct engagement in this response—Andrea Smith’s analysis of privilege directly shapes the questions of poverty, class and subjectivity raised by the Occupy movement. Smith, Andrea. “The Problem With Privilege.” http://andrea366.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/the-problem-with-privilege-by-andrea-smith/↩

http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.vanityfair.com/society/features/2011/05/top-one-percent-201105#↩

At least in terms of the misconstrued conflation of consumptive desire and that of equal opportunity. Such complexity, and its interpretive implications, were captured in the sentiments of one highly cited protester in the controversy surrounding Trinity Church: “We need more. You have more.” http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.nytimes.com/2011/12/17/nyregion/church-that-aided-wall-st-protesters-is-now-their-target.html↩

Éduoard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, translated by Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 5.↩

Ibid., 6.↩

Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010),186–87.↩

Ibid.↩

Glissant, 8.↩

Fred Moten, “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh),” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (2013) 737–80.↩

Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 36–39.↩

Glissant, 9.↩

Martin Luther King, Jr. “Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963).” A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., edited by James Melvin Washington (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1991), 290.↩

10.22.14 |

Searching for the Multitude in Occupy Religion

“If hope is an impossible demand, then we demand the impossible.”

—Judith Butler at Occupy Wall Street October 2011

In the fall of 2011, an uprising began to take root on Wall Street. Dissatisfied with the current malaise of American politics, protesters spanning ages, genders, classes, sexualities, and abilities began to occupy Wall Street. Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude is the religious and theological reflection on this movement, which spanned the country and even had a global footprint. In many ways, the year 2011 was a year of incredible revolutionary activity. The largest global occupy movement crystalized in October of 2011; this movement was motivated by activity in the U.S., the riots against austerity measures in Europe and the UK, the occupations in Wisconsin, and the occupations by the Spanish indignados. Each of these occupations was also inspired by the Arab Spring and the uprising that was brewing globally. The political subject in the United States became a visible subject whose consciousness called for a future that sought to not only destabilize and deconstruct, but completely reorder the matrices of oppression, particularly those oppressions that are tied to the all-American U.S. dollar. Yet, Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude does not address the displaced consciousness; rather, it narrates the authors’ interpretation of the Occupy movement. In narrating their interpretation of the Occupy movement and also pointing to social media sites that carry the anthem of the 99 percent, this book essentially flattens out the Occupy movement and constructs a theology, albeit diffuse and culturally white, that does not advocate for the multiplicity that commonly emerges in French post-war philosophy, or inherent in the global uprising and occupations. I believe this is a severe oversight for Rieger and Kwok in that this “theology of the multitude” relies on a concept of unity and singularity, over against difference and multiplicity.

I wish to focus on the concept of multiplicity and the political subject that is identified in this book. I will suggest that the political subject that is part of the Occupy movement is a subject focused on the concept of futurity demanding a radical and conscious orientation to a type of atheistic hope. Henceforth, the concept of multiplicity is rooted in an ontology of difference as becoming, not in a difference in unity, which is what Rieger and Kwok theorize (59).

The focus on multiplicity in Occupy Religion uses the modern/liberal concept of traditioning and religion to substantiate their claim.

Because of the radical differences that exist within the multitude (the margins of the margins), for example, being as differences, a theology of multiplicity must begin not with those voices or concepts which are easily normalized into the multitude, but rather, as Marcella Althaus-Reid says, the indecent. It is the indecent who radically destabilize the multitude and provide a framework of radical difference to rethink theology, ethics, praxis, and the intersections or entanglement of these three. While I appreciate the stories that are contained in this book (and I believe it is important for those stories to be told), the narratives in this book from Occupiers are not indecent stories; they are decent. The narratives construct a stable multiplicity that does not expand or contract relative to indecency, or the perversion that exists at the margins of the margins. This, I suggest, is the being of differences. A theology of multiplicity should begin with an ontology of becoming different, not stem from the stable constructive tools of feminism, LGBT theologies, and other minoritized theologies.

The political subject, now visible in the Occupy movement, is rendered angry and fed-up with the American political system. While this might be true for many of the Occupiers, the significance of flattening out the political subject and not recognizing their complexities, significantly affects the outcome of a theology of the multitude. The Occupy movement generated a political subject that resulted in multiple epistemological ruptures across varying differences and demanded a new utopic vision. In many ways, the Gay Liberation Movements generated new political subjects that reached backward and forward toward a new and radically open future. The Occupy movement has done the same, but Occupy Religion does not speak to the complexities of the political subject of the Occupy movement, rendering the political subject analogous to the white liberal progressive. This undermines the indecency of the political subject that was central to the Occupy movement. The theology of the multitude, as explained in Occupy Religion, does not take revolutionary politics or revolution seriously. Occupy Religion relies on a theology of reformation, instead of revolution, constructively understood as the actuality of the Occupy movement.

The political subject of Occupy Religion focuses primarily on the ways in which reforming political systems has not worked and the networked viability of community that emerged as a result. What is missed, however, is the manner in which the Occupy movement resisted negotiating with political parties, seen primarily as potential co-optations. The reality that the Occupy movement has not handed over a list of demands tells us that they are not interested in political reform. The theology and politics of resistance that is so apparent in the Occupy movement is not picked up and developed as part of the theology of the multitude in Occupy Religion. This makes the political subject diffuse in the book, undermining the great potential that the Occupy political subject enfleshes. The political subject of the Occupy movement necessarily exemplifies that another world is no longer possible—political representation has failed us miserably; instead, another world is becoming actual. This is where French post-war philosophy can add a significant set of theory tools to Occupy Religion and create a much more robust political theology. I suggest Deleuze and Guattari’s political constructivism; it is entirely illuminating.

To pick up the strand of atheistic hope, I recall Judith Butler’s speech at Occupy Wall Street. She said: “If hope is an impossible demand, then we demand the impossible.”Demanding the impossible as that which is rooted in hope is not the resignation to a form of hopelessness, but rather the vision of a utopia that is rooted in atheistic hope. José Estaban Muñoz captures this when he details Gloria Anzaldúa’s vision of la communidad de joteria. He says: “Anzaldua’s injunction to look for joteria [translated as queers, which she asserts can be found at the base of every liberationist social movement] is a call to deploy a narrative of the past to enable better understanding and critiquing of a faltering present. In this sense her call for mestiza consciousness is a looking back to a fecund no-longer-conscious in the service of a futurity that resists the various violent asymmetries that dominate the present.”

J. Z. Smith argues that religion is a creation of the academy and doesn’t actually exist.↩

ven some versions of “queer theologies”are rooted in stable identity categories and rely on binary systems to construct their theologies.↩

See Thomas Nail’s “Deleuze, Occupy, and the Actuality of Revolution,”Theory and Event 16, no. 1 (2013). See also Deleuze and Politics.↩

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 84.↩

10.23.14 |

Theology at the Service of Humanity

“I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security”

—Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 49

Like the authors of Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude, I find in many of my encounters with U.S. Christian communities the assumption that Christianity is clean, comforting, friendly, moderately well-off, and capable of making the world a better place by giving some aid to people in need. Like the authors, I find the vitality of faith in communities where the gospel has led people into a more costly, less certain, more joyous form of life together. I sympathize with the authors’ work to call attention to God’s presence with people in their struggle and to a church that is a diverse community of people engaged in that struggle. Like them, I see in the Occupy movement an invitation and challenge to Christian communities. And like them, I work to understand “the ways religious sentiments and concepts have been used to reinforce . . . domination” (62). My own work on the history of Christian “stewardship” attempts to address this very problem.

But for all that, I disagree with the authors’ analysis of what has gone wrong and with their agenda for addressing it. Though I share their conviction that theology matters, I hold that its crucial task—for the good of all—is quite other than what the authors propose.

The authors of Occupy Religion argue that “theology is not a luxury, but finds itself at the heart of efforts to present alternative ways and solutions” (58). Theology’s role is two-fold: first, to address “the ways that religious sentiments and concepts have been used to reinforce . . . domination” (62); second, to promote understandings of power as bottom-up and of the Other as honored collaborator, by giving accounts of God that support those values so that social life may be organized around such a vision. They engage certain questions of Christian theology, but their focus is on promoting among all people an understanding of power and difference that will support the struggle of the multitude. “Our project is not reconciling different notions of divinity, whatever they may be, but reimagining divinity in all religions” (90). While they expect their account of God to be new to most people, they also hold that for the Occupy movement’s 99 percent, religion matters as “a multiplicity of popular traditions that preach not only concern for the least of these but also a reversal and broadening of power, which moves from the bottom up, so that all can participate in the production of life” (28).

Theology, then, matters because different accounts of God’s power are at work in the world, some that perpetuate oppression and some that recognize and encourage pluralistic, widely-distributed, creative power for the multitude. Theology that is faithful to the best of what humans have learned about God will speak of a God who is present in the struggle. The authors focus on Christianity, presumably because it is their tradition and the faith most commonly appealed to in the US. It is a major part of the problem; it could be a major part of better solutions. Their concern is not doctrine set in the past, particularly when that past has included many examples of God’s name being used to justify oppression. What matters is a practical, diverse, open-ended, shared struggle for a new society.

Rieger and Kwok identify their theological enemy as “status quo” or “mainline” theologies. “The deepest problem of our most common images of God, supported by conservatives and liberals alike, is that images of the divine as omnipotent, impassible, and immutable tend to mirror the dominant power that be, from ancient emperors to modern CEOs” (88). This belief in and adoration of top-down power is a key to an oppressive symbol system, as they see it. They do not cite any specific present-day authors who are responsible for promoting this view, perhaps because they take it to be “virtually omnipresent” (96). But the generality of the claim leaves me wondering: who is promoting this view and how? Who accepts it and why?

The authors themselves give plenty of evidence that Christian theology is not entirely sold out to this status quo enemy. They acknowledge that Rowan Williams explicitly and the Vatican implicitly approved of the Occupy movement’s claims about economic injustice, as did many other religious leaders. They also find support for their critique in Barth, whom the authors see as allied with liberation theology. These are not “status quo” theology. And the monarch God that mirrors human domination is not the God we would find in, say, Augustine, nor in Moltmann, Tillich, Rahner, or liberation theologies, nor even in present-day Thomists, from Kathryn Tanner to Matt Levering, who hold that God acts within the freedom of each creature in a way that is not competitive with creation. Where then does this top-down monarch God legitimating the status quo come from?

The image of God as monarch is common in Christian tradition—in scripture and iconography and hymnody. And this image certainly may serve, and has served, to bolster despotic rule. But the problem is not in the image itself. The authors hold that Jews or Christians who want to be “truly faithful to the God of their traditions” do not embrace this top-down God (89). That is, the image functions differently when it is encountered in the full context of those traditions. God’s kingship in scripture exists as a contrast to human kingship and a judgment against abusive human rule; in John, Jesus’s kingship is strongly linked to his rejection and crucifixion. A serious engagement with God as king, in Christian theology, does not function simply to encourage admiration and confidence in human rule.

Nevertheless, the popular image of “the man upstairs,” uncomplicated by any sense of paradox or limits of analogy, is widespread, and it may simply be this that the authors have in mind. My point is that this sort of faith is less the result of the texts and practices of hierarchical or “expert” Christian traditions than to a cultural context that frees religious images from the bounds of tradition or the authority of saints and teachers, making faith a matter of personal preference, with little intrinsic relation to social reality.

Studies on the impacts of cultural changes give insight into what is going on with religious thought and practice.

The problem is not that believers need to discover a new kind of God. They do not know the God of their own traditions. We have evidence that basic knowledge of religious traditions, including Christians’ knowledge of Christianity, is very poor.

Rieger and Kwok see a shrine holding images of John Lennon, Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Buddha, and Gandhi alongside other objects of spiritual significance as not mere toleration but a sign of “respecting the integrity and the otherness of the other” (129). It strikes me, in the absence of serious discussion about the nature, value, and challenges of interreligious dialogue, more as an example of such fragmentation. Well, but what’s wrong with that? Mutual respect is a good thing, right? Maybe, after all, strawberry fields forever are a better way for humanity to go, at this point.

Aside from its spiritual compatibility with global capitalism, which can make a lot of hay out of respectful appreciation of diversity as an occasion for broad and restless consumer appetites, a major problem in this commodification of religious images is that this way of engaging religious faith strikes shallow roots in real life. A few people may come to the shrine of diversity with deep lived knowledge of a faith and discover new ways to deepen and challenge their faith. But they are the exception in our society, and growing more so.

I don’t despair, though I am a bit grim on this account. I have seen Christian communities committed to arguing and living together, sharing resources (even to going into debt for each other’s sake), struggling to come to consensus about what their baptismal call means, sticking together through long, hard arguments, praying across great diversities before the God to whom they all belong. They do not escape who we are now. But they dig in to a place, a city, a community, a tradition of revelation in ways that give me more hope than Occupy’s spirituality does. What distinguishes them is that they were held by the authority of Christian tradition to mutual love of each other and of God.

So I want to talk—in perilously brief terms—about authority and revelation, not categories that lend themselves to brief treatment.

As I noted before, the authors of this book and I all hold that theology matters. For them, it is serious because it either supports or blocks the progress of humanity in this moment of crisis. I take it to be serious business because it is an attempt by a community of faith to speak truthfully about God. We do it poorly, even the best of us at the best of times. The apophatic tradition is not wrong. And the attempt to do it only makes sense if we presume that there is such a thing as revelation, a gift of God to enable us to encounter and enter into, in a creaturely way, God’s own life. As Dei Verbum

Because there is such a thing as revelation, we can talk about theological teaching authority as distinct from arbitrary power. Authority is a category the authors do not engage, though they talk about power with insight and attention. It is a two-way relationship shaped by shared, if in some ways still contested, commitments to a common good. It serves a community full of capabilities not by shutting others’ agency down but by coordinating and maintaining focus toward a shared end. The play of authority is complex; the authority of bishops and that of saints work in tension and sometimes in outright conflict with each other. I will not pretend that it is safe from abuses. But then, avoiding discussion of authority is not safe either, particularly in a consumer culture. Human communities do appeal to more or less clearly defined authorities as part of their shared conversations. Explicit authorities accountable to explicit goods are easier to challenge and correct than are hidden authorities serving unspecified ends. At any rate, it is authority—prophetic or even institutional, as in the case of the Vatican’s leadership on climate change and economic injustice—that demands a community recognize uncomfortable truths spoken by those outside the inner circle. Authority can be held accountable for doing that if, that is, it is an authority that takes the Jesus of the gospels to be the Word of God. In such a case, inconvenient doctrines cannot be dismissed.

A community in which the practice of authority is accountable for its service to the person of Jesus might be able to go beyond enthusiasm for the other and get to love of neighbor and enemy. That does not mean such a community will be a haven of sweetness and light. Dorothy Day wrote, “I loved the Church for Christ made visible. Not for itself, because it was so often a scandal to me. Romano Guardini said the Church is the Cross on which Christ was crucified; one could not separate Christ from His Cross, and one must live in a state of permanent dissatisfaction with the Church.”

As a Christian theologian, working principally in and for that community, I have had to abandon all hope of purity, all claims that I am going to make it right, and all aspirations to speak to and for everyone. I can sympathize with the desire to find a way into a simpler, brighter version of the church, a fresh new Jesus movement not burdened by conflict and failure.But history teaches me that such attempts are unlikely to work out as their originator’s plan.

At any rate, the theology that I take seriously works at speaking well of God, depending for that effort on revelation in events leading to and following from Jesus’ life as in scripture and in tradition, where discernment about degrees of authority and struggle over contesting accounts of authority are always part of the process. Liberation theologies gave to the discipline a great and costly gift in their insistence that theologians attend to their participation in material conditions of injustice as a force in their own intellectual work and in the life of the church. The reason that principle has become so widely influential is that it demands theologians to speak more truthfully, and theology has to be about speaking and living in truth. It is that responsibility that makes theology complicated, important, serious, dangerous, and, ultimately, life-giving. If it does not do that, then we can give it up and become screenwriters, who, frankly, seem better than theologians at creating images that move people.

For these reasons, the claim that a theology that is serious about its own role should entirely “re-imagine” God and church so that it will better serve the needs of the world strikes me as profoundly confused.

I want to note, in closing, that this is a book written for a general audience, which makes it all the more important. This kind of scholarly effort ought to be a priority for theologians in our time. We have an unprecedented number of highly trained lay people giving their lives to theological scholarship and still we have abysmal rates of religious literacy among non-specialists. A large swath of Christians in the U.S. do, more or less, fit the charges Rieger and Kwok level at them, and theologians bear a significant part of the blame. Good scholarship alone will not fix our problems, but it is our responsibility at least to help Christians (ourselves included) to speak more truthfully about God and humanity. As we take up the challenge to produce theology for a general audience, let us not abandon what seems awkward about our discipline, what will require our readers (and ourselves) to think outside convenient categories. Let us not resort to straw-man arguments that draw non-specialists into the misunderstanding and mistrust so frequently found in the academic guild of theology. We who teach and write theology, whatever else we may be about, ultimately serve humanity by producing the best theology we can manage, for love of God and all of God’s good creation.

Kelly Johnson, Fear of Beggars: Poverty and Stewardship in Christian Economic Thought (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007).↩

I am particularly indebted to Vincent Miller in Consuming Religion: Christian Faith and Practice in a Consumer Culture (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2005); for Michael Budde’s The (Magic) Kingdom of God: Christianity and Global Culture Industries (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998); and Christian Smith with Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).↩

http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.pewforum.org/2010/09/28/u-s-religious-knowledge-survey-who-knows-what-about-religion/↩

The fastest-growing religious identification in the U.S. is the “nones.” These are the religiously unaffiliated, who, when faced with a checklist of religious identification on a form check “none.” http:/C:/dev/home/163979.cloudwaysapps.com/esbfrbwtsm/public_html/syndicatenetwork.com4.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/↩

Vatican II, “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation.” www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html.↩

I refer those who are interested in this point to Margaret Adams’ study of Moltmann’s influence. Our Only Hope: More than We Can Ask or Imagine (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2013).↩

Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1952), 149–50.↩

I adapt this from a quote from one I heard Roberto Goizueta attribute to, I think, Virgilio Elizondo: “The poor deserve the best theology we can give them.”↩

Helene Slessarev-Jamir

A God of Justice or a God of the Status Quo?

Spurred on by the Occupy Wall Street movement, Joerg Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan have engaged in a serious reflection on the “social and economic teachings of the church, and its images of God” in an effort to set forth a public theology that meets the challenges of our time. Given the increasing public presence of conservative Christianity in American politics, Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan aim to elaborate a theology that does not seek to dominate, but contributes as one element within the larger, diverse struggles for global liberation. Although writing primarily for American audiences, both authors also speak to the new realities present in many countries that have also experienced greater economic inequality. This includes the former communist countries of China and Russia, which are quickly transforming themselves into postmodern oligarchies. In times such as these, there are no positions of neutrality.

The book’s primary focus is the Occupy Wall Street movement, which burst forth from Zucotti Park in lower Manhattan at the height of the global recession in September 2011. The protest encampment in the middle of Wall Street focused a global discussion on the negative consequences of the enormous wealth disparities present within the United States as well as globally between the 1 percent and the 99 percent. While the physical occupation proved to be fleeting, the Occupy movement has indeed opened up new spaces for on-going conversations, as the authors suggest, especially engaging young adults who, in many cases, had no previous experience as political activists. The practices of direct democracy at the heart of the Occupy movement, sought to model new forms of political life that are in sharp contrast to the backroom dealings that characterize much of conventional American politics, where corporate lobbyists routinely exchange cash and favors for legislative votes.

Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan applaud the new forms of horizontal leadership practiced at the Occupy movement’s assemblies as facilitating the emergence of new leaders and enabling “the potential of people to claim their agency and create something entirely new.” While this was undoubtedly true, one must also raise a certain cautionary note when analyzing OWS and other recent mass movements for democracy. Here I echo the concerns raised by Tariq Ramadan, the professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies at Oxford University, in his analysis of the series of recent popular uprisings in the Middle East that are collectively known as the Arab Spring. In that case, cyber-bloggers were also key in effectively spreading a call for non-violent resistance to dictatorship to a younger, internet savvy generation hungry for real democracy and greater economic opportunities. Beginning in Tunisia in December 2010, the uprising quickly spread to Egypt, where it sparked massive non-violent protests in the center of Cairo beginning in late January 2011. Despite the euphoria surrounding these events, Ramadan is incisive in recognizing that the lack of on-going democratic discourse over possible alternative economic and political structures prior to the uprisings meant that while the protestors had a clear idea of what they did not want, “they struggled to give expression to their social and political aspirations beyond the slogans that called for an end to corruption, cronyism, and the establishment of the rule of law and democracy.”

This phenomenon was to some extent also true of the Occupy Wall Street movement. While broad, public calls for greater democracy and a more equitable distribution of wealth serve as valuable starting points for on-going processes of social change, such calls must have the capacity to move beyond slogans and broad calls for change to the hard work of developing concrete strategies for winning long term political and economic reforms. It was on this critical dimension of actualizing the multitude’s grievances into concrete strategies for political and economic change that these twin protest movements fell short; a reality downplayed by our two authors.

Nonetheless, both Occupy Wall Street and the encampment in Cairo’s Tahrir Square did serve as sites of experimentation for new forms of direct democracy. They enabled masses of people to fearlessly give voice to their grievances in very public forums, during which both women and youth gained unprecedented visibility as emerging leaders.

While Occupy Wall Street effectively transformed the silent suffering of millions of Americans who were losing their jobs and their homes during the Great Recession into a national crisis, it ultimately also fell short in its ability to chart an alternate way forward. Thus the overwhelming power of globalized capital continues to challenge both secular and religious justice activists to search for new, still more powerful forms of organizing with the potential to successfully dismantle the egregious wealth disparities and their concomitant political power differentials. However, given the enormous power that Wall Street exerts over the whole of New York City and its institutions, more just political and economic paradigms are perhaps less likely to spring forth from the concrete pavements of that city than from locations of greater liminality. Perhaps we need to look into the fissures and cracks of American empire to identify new, emerging activist paradigms.

I suggest that one of the places where we might search for fresh liberative paradigms of justice activism are those spaces located at the margins of American empire. One of these locations are the border regions where the old Spanish empire intersects with the postmodern American empire, namely, in the southwestern edges of the United States. Here I am in part drawing on the work of Walter Mignolo, whose book entitled, Local Histories/Global Designs, argues that it is at such intersections that “the epistemological potential of border thinking, of ‘an other thinking’ has the possibility of overcoming the limitation of territorial thinking.”

The southwestern regions of the United States have indeed been the sites of militant contestation over labor and immigrant rights for decades, stretching back into the early 1950s. In the 1960s, the United Farmworkers captured the American public’s imagination with its highly effective national grape boycott along with its public pilgrimages, always led by a statute of the Virgin of Guadalupe who is the embodiment of a hybrid people born out of the Spanish conquest of Mexico over five hundred years ago. By the 1980s, the Justice for Janitors campaign launched massive protest marches through the streets of downtown Los Angeles in opposition to building owners’ attempts to break the janitors’ union.

Drawing on the lessons and seasoned leadership of these mass-organizing campaigns, Latino immigrant workers were transformed into active political subjects, who in the course of asserting their humanity, successfully reshaped the politics of southern California. At present, much the union and elected leadership of the city of Los Angeles, including former mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and the current mayor, Eric Garcetti, have their roots in the region’s protracted struggles for economic justice.

While Latino workers continue to be at the center of this region’s justice work, other immigrant groups, including Koreans and Filipinos, have built their own organizing capacities to take on employers in their particular ethnic communities. In turn, the workplace organizing intersects with immigrant rights organizing since many of the lowest paid workers in the southwest and elsewhere in the United States are immigrants, often those without legal documents. The key to much of this work has been its focus on organizing people who are without formal citizenship rights, yet are fighting for their rights to more life from below.

The large numbers of diverse immigrants in the southwest has transformed the region into an incubator for ongoing collaborative work between multiple different organizations committed to securing justice for the most marginalized, such as day laborers who stood on the city’s street corners looking for work every day. This activist work, done over several decades through a multiplicity of interconnected organizations, has objectively improved the economic status of millions of low wage immigrant workers, despite the increasingly punitive anti-immigrant policies that have emerged from Washington DC since 1996.

I am suggesting that broad based coalitional organizing in the border spaces of American empire currently constitutes a primary challenge to the powers of empire. It is here that the multitude is most visible in asserting its claims to more life. Organizing in these spaces can also lead to tangible improvements in the well-being and self-efficacy of people situated on the very margins of American empire.

Although the Occupy Movement was largely secular in nature, Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan note the significance of the active participation of people of faith from many different religious traditions within the movement. However, here again I would caution against attributing too much of this new found visibility to the Occupy Movement itself. Progressive forms of interreligious activism have been on the rise for several decades, mostly embodied in local interfaith collaborations around peace-making, worker justice, community organizing, and immigrant rights work. Organizations such as Interfaith Worker Justice based in Chicago and Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice in LA have existed since the mid-1990s and are currently expanding their interfaith reach beyond the Abrahamic faiths. Over time the interfaith dimensions have also grown well beyond initial practices in which activists quote a few relatively similar passages from each other’s textual traditions to a much deeper recognition of the presence of a multiplicity of truths within our world’s collective spiritual traditions. Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan correctly recognize that Christian liberation theologians may well have more in common with liberation theologians from other religious traditions than with Christian conservative theologians who uphold the dominant images of a God of top down power.

As I have participated in varying forms of activism within the southwestern border region in which I now live, I have come to understand that much of this work is undergirded by the simultaneous presence of a multiplicity of spiritualities that course through the veins of this land and its people. Some of them are local and indigenous, while others are global in their origins. They not only create meaning in the midst of hardships and struggles, they also give identity to people whom the dominant society and the powers of empire view as insignificant, and therefore expendable, in their totalizing worldviews.

These experiences align well with Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan’s assertion that “the heart of the theology of the multitude is not religion in general but an experience of otherness and transcendence, which can be mediated through religion as well as through other experiences” (73). In contrast to a number of postmodern theorists, Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan value the many unique contributions that religion can make to the struggles of the multitude. It is certainly true that Jesus not only lived in deep solidarity with the multitude; he was incarnated as a member of the multitude, “particularly those who struggled with life,” which continues to be the daily reality of the multitude. This is truly the God of those whose lives are falling apart!

The marginality of God incarnate in the bodily form of Jesus of Nazareth is truly astounding. According to Reza Aslan’s book The Zealot, the hamlet of Nazareth where Jesus is said to grown up was so obscure that its name does not appear on any ancient Jewish maps before the third century C.E.

I resonate deeply with both authors’ recognition that humanity is not simply a collection of individuals, but that instead we are bound together in community. Having initially become a Christian in the context of a lower income African-American church, my early church experiences were strongly shaped by the communal nature of the body of Christ where members cared for one another, relying on each other in moments of crises. That strong sense of community radiated out beyond the tiny building in which we worshipped into the surrounding neighborhoods that were being devastated by the shuttering of the steel mills on the Southside of Chicago.

In my own work on prophetic activism I have also recognized the centrality of rethinking theology in ways that open up “an other thinking.” Processes of social change cannot be erected on the basis of a God of the status quo. Those of us who self-identify as progressive religious activists now stand on a rich intellectual legacy that stretches back to earlier dissenters such as Henry David Thoreau who was imprisoned because of his refusal to pay taxes in protest against the US government’s unwillingness to end slavery and its pursuit of war against Mexico. We are also the inheritors of Mahatma Gandhi’s principles of active nonviolence, which he drew out of his scared Hindu texts. As the early twentieth-century leaders of a nascent American civil rights movement searched for a way forward, they came to embrace Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, recognizing that active nonviolent resistance was the only means by which African-Americans could bring down segregation.

Yet, despite the history and ongoing vibrancy of progressive religious activism, it appears to have relatively little impact on the institutional church itself, which too often remains stuck in older paradigms of a patriarchal God of the status quo. I find that congregations often remain reluctant to engage with the tough issues of economic inequality and justice for those who are marginalized, even when they are represented amongst those seated in the pews on Sunday mornings. It is reflective of the individualism of large parts of American Christianity as well as a reluctance on many people’s part to admit that their own backs are up against the wall. Too often church bible studies become exercises in repetition of well-worn biblical formulas rather than a deeper interrogation of the texts. These habits greatly weaken the ability of the church itself to speak more forcefully into the midst of the deep global divide between the 99 percent and the 1 percent.

I strongly affirm the authors’ call for a democratization of sacred space that would involve doing church instead of going to church. There is clearly a need for much experimentation in being church in new and more meaning ways that both confront the powers that be while also offering spaces of comfort and solace to those who are being bodily and spiritually wounded as a consequence of the enormous gaps in wealth and well-being.

Tariq Ramadan, Islam and the Arab Awakening (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012,) Kindle edition, Location 1212.↩

Walter D. Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledge (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000) Kindle edition, Location 1922.↩

Reza Aslan, The Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth (New York: Random House, 2013),Kindle Location 604.↩

12.24.14 | Kwok Pui-lan

A Response to Helene Slessarev-Jamir

Helene Slessarev-Jamir’s essay points to some of the shortcomings of the Occupy movement and shares the experience of political organizing in border spaces in the southwestern region of the United States. Tariq Ramadan notes that there has not been a democratic discourse of alternative economic and political orders before the Arab Spring, and protesters struggled “to give expression of their social and political aspirations beyond the slogans.” The situation of the United States where the Occupy movement started was quite different from that of the Middle East. Grassroots movements, commentators in the media, bloggers in progressive sites, and even some politicians were highly critical of the bailing out of big banks and businesses. There were other reasons that the Occupy movement did not issue a clear political platform with concrete strategies for long-term social change. First, the protesters decided not to work within the existing political party system, because they saw that the system was broken and corrupted by money and corporate lobby. Second, their commitment to direct democracy meant that there was no headquarter or central governing body that would articulate a set of demands and concrete strategies to achieve them. The movement was quite decentralized and organized by local people with rotating leadership. Third, there was great diversity among the protesters. While the demands for greater economic equity and political participation are common goals, people have also included a wide range of concerns: environmental crisis; the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people; women’s concerns; student loans; and unemployment, to name a few. Fourth, the police raided most of the encampments within three months after the Occupy movement started in September 2011. Although some protesters continued to meet in churches and public spaces, the movement lost momentum and did not have sustained energy to work out long-term strategies.

When the protesters were occupying the camps, some commentators criticized that the movement could not achieve its goals without concrete planning and action, similar to that which Slessarev-Jamir says in her essay. As authors, Joerg Rieger and I are aware of these criticisms. Yet we wanted to emphasize the revolutionary potential of a movement that had gathered and galvanized a multitude of people and opened spaces for direct democracy and radical politics. The movement pointed out we could not do business as usual, and created an animated political culture with posters, slogans, songs, livestream videos, websites, rituals, and social media. This creativity and the participation of so many different kinds of people had not been seen in years.

We need different kinds of social movements and political organizing because the concentration of power and wealth of the 1 percent is so insidious and multifaceted. I agree with Slessarev-Jamir that the kind of long-term organizing for immigrants and undocumented people that she describes is very necessary for social and political transformation. She has also documented other forms of faith-based progressive activism in America in the past several decades in her important volume, Prophetic Activism: Progressive Religious Justice Movements in Contemporary America. She presents insightful case studies about congregations and organizations working for worker justice, immigrant rights, peacemaking and reconciliation, and global anti-poverty and debt relief.

But there is also a place for creative and massive movements like the Occupy movement. The movement has changed the political discourse and conscientized many people on the globe about the power of people as historical subjects. In the United States, it sharpened the debates on economic injustice during the 2012 Presidential election. President Barack Obama said that the growing income gap is a “defining challenge of our time.” In his State of the Union address delivered in January 2014, he talked about reversing income inequality and raising the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour. This is a good start, even though there is still a long way to go. Around the globe, the idea that people have a right to occupy public spaces and to demand their voices be heard has caught on. In March 2014, hundreds of students and protesters in Taiwan occupied the Legislative to protest against the ruling party’s push for a trade pact with China. In September 2014, tens of thousands participated in the Occupy Central movement in the financial district and other parts of Hong Kong to demand universal suffrage for the chief executive election in 2017, according to international standards.

Slessarev-Jamir laments that many churches are oblivious to economic inequity, and progressive religious activism. The institution church, she says, remains “stuck in older paradigms of a patriarchal God of the status quo.” I would say that this is one of the reasons that membership of mainline denominations has been in decline, because the churches have become increasingly irrelevant. To be faithful and relevant, it is important for the churches to revitalize the prophetic imagination that the Hebrew prophets and Jesus had taught, and to be actively engaged in movements to change the world for the sake of the Kingdom.