From Christ to Confucius

By

8.28.17 |

Symposium Introduction

In From Christ to Confucius: German Missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Globalization of Christianity, 1860-1950 the historian Albert Wu tells the story of how German Protestant and Catholic missionaries to China underwent a radical reversal in their thinking about Confucianism. “Why”, ask Wu, “did German Catholic and Protestant missionaries argue in 1900 that Christianity’s success depended on Confucianism’s demise, and how, by the 1930s, did they come to view the fates of Christianity and Confucianism as inseparable?” According to Wu, as a consequence of War World I, German missionaries began to move away from their dogmatic association of Christianisation with Europeanisation. Moreover, by the 1920s the threat of fascist and communist ideologies compelled these Christian missionaries to adapt to local concerns and cultures in the hope of finding allies in China. In the process Christianity became more Chinese.

Slowly the ecclesiastic structures of these missionary efforts to China were indigenized allowing for an allying with Confucian ideas and practices that were previously held in contempt. By the time these missionaries left China in the 1950s, they had become Confucianism/s ardent defenders. “Through their encounter with China,” says Wu, “missionaries began to reconsider Christianity’s relationship to other religions, and ultimately began to re-examine central tenets of Christianity, such as the exclusivity of Christian salvation. German missionaries, the book argues, were agents of both globalization and secularization.”

The book, therefore, puts forward an alterative understanding of why the Protestant and Catholic churches experienced high levels of secularization in the 1960s. It was not Vatican II or the loosening of traditional norms that led to decreasing numbers in the pews. Rather European missionaries positive views of rival religions and cultures “sowed the seeds for Christians in the 1960s to reject Christianity’s exclusive salvationist claims.” One can assume here that Wu’s argument also applies to mainline liberal Protestant missionaries who equally sowed the seeds of secularization in the United States. Wu’s alternative secularization thesis is one of the most fascinating aspects of the book. Moreover, scholars will glean much from the copious archive research he has carried out in both Germany and China.

For this Syndicate Theology forum we have invited five excellent scholars to comment on Wu’s fascinating book. Brian Stanley, Professor of World Christianity at the University of Edinburgh, praises Wu’s valuable the erudition of Wu’s attempt to chart the evolution of the missionary’s thinking about Confucianism. He wonders though if Wu has provided compelling evidence that their change of outlook had anything at all to do with the secularization of the German churches in the 1960s.

Justin Youngchan Choi, who studies the influence of Protestant political thought in Korea at the University of London, raises the question of how Wu’s argument might apply to Protestant missionary efforts in Korea which were far more successful there than in China. As he intriguingly puts it: “Given the nearly identical set of cultural, intellectual, and institutional challenges faced by the Christian missionaries – not to mention tremendous overlap in the personnel circulation between the two countries – the arguments of Wu appear to invite us to explain the diverging growth trend of Korean Christianity dating back to 1910, particularly given that conservative Presbyterians rose vertically while more liberal Methodists stagnated?”

Jonathan Bonk, who is research Professor of Missions at Boston University, praises From Christ to Confucius for being one of the clearest, most succinct overviews of the 19th century missionary impulse that he has ever come across. His comment refreshingly draws from his own personal experiences with Chinese missionaries and students in the attempt to illustrate the finer points of Wu’s argument.

Steven Pieragastini, who teaches history at Boston College, agrees with Wu’s thesis on the indigenization of Christianity while defending Wu’s attempt to oppose a longstanding tradition that reduces European missions to a mere extension of empire. He does wonder if the missionaries new found respect for Confucianism was simply a larger trend of a growing appreciation for Sinology in Europe.

Finally, the historian John Chen of Columbia University, lauds Wu’s research findings. In doing so he wonders if China’s constrained “political atmosphere played as large a role in Chinese Christians’ calls to make the church more Chinese as did their relations with the German missionaries.” Most interestingly, he raises a series of questions involving the role of Islam in China in order to bear light on Wu’s thinking on Christian missionaries there.

Wu responds to each of his critics in depth. And in all it is an enriching forum that is sure to profit Syndicate Theology’s readership.

8.31.17 |

Response

Commentary by Jonathan Bonk

Albert Wu is to be congratulated for his satisfyingly instructive book. The story of how German missionary regard for Confucianism evolved from highly critical caricature to measured appreciation is framed by tumultuous social and political convulsions over which they had no control and unfolds within opaque cultural contexts of which they had little comprehension. The book blends into the much larger canvas, still unfinished, featuring Western civilization’s relinquishment of its founding religion, and the appropriation, reinvention and revitalization of that religion beyond its old hinterlands, throughout the non-Western world.

In keeping with the instructions provided, this is neither a review nor a summary, but a partial record of personal thoughts elicited by the book as I read it. I am neither a sinologist nor, strictly speaking, a historian, but a missiologist, an editor, and sometimes visitor to China. My comments may be written in the declarative voice, but they are also questions, welcoming response and clarification.

The book is, necessarily, several inextricably entangled and unfinished stories. The story of Western political, military, economic and to some extent religious ascendancy, hegemony, and decline; the story of the processes of cultural and religious dynamism and decay, conversion and renewal; and a compelling illustration of Reinhold Niebuhr’s argument in Moral Man and Immoral Society. Western missionary racial views were conditioned and shaped by their social contexts. During the period of this book’s purview no Western society was free of racial bigotry, and nor is any today.

It was during this period that the Western world evolved its most sophisticated, “scientific” racial theories. Measurable proofs provided by polymath Francis Galton, and father of eugenics. Eugenics—supported by theological rationalizations—provided justification of slavery and other forms of racial domination as relatively benign, divinely sanctioned ways to ensure the survival and eventual elevation of feebler races.

Introduction: Perceptions of Failure. The West’s sense of cultural, political and moral superiority was not easy to shed, being the culmination of a centuries-long process of global exploration, economic exploitation, military conquest, political expansion, and human genocide. Western missionaries held their religion to be the “inner élan” of this ascendency. Ethnocentrism is inevitable in all cultures and societies, but when supported by military superiority, territorial conquest, and material dynamism, it is almost impossible to gainsay. After all, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the nations of old Christendom dominated all of Africa, the entire Middle East except for Turkey, and most of the Asian subcontinent. The 35 percent of the earth’s surface controlled by Europeans when Carey sailed for Serampore (1793) had grown to 84 percent by 1914. The British Empire, encompassing 20 million subjects spread over 1.5 million square miles in 1800, had swollen to 390 million people inhabiting 11 million square miles a century later. As Wu reminds us, this apparently inexorable expansion of European domination occurred on multiple levels, including religious. The superiority of Western worldviews and institutions seemed obvious.

Then came World War I, a retrospectively unnecessary calamity of death and destruction that convulsed Western nations, and laid bare the naïveté of missionary assertions and assumptions regarding the superiority of Christian civilization. Missionaries were unable to offer any credible rejoinder to the charge that the West neither believed nor practiced what the Bible actually taught.

This was in many ways a Christian civil war, a point that Philip Jenkins argues quite convincingly in The Great and Holy War: How World War I Became a Religious Crusade (New York: HarperOne, 2014). The protagonists were “Christian” or Abrahamic nations who aroused their populations and justified their violence by drawing upon religious apocalyptic language, metaphors and dark prophecies. For each of the protagonists, this was a Holy War, fought against the enemies of God on behalf of God.

This was perhaps especially true of Germany. As Jenkins notes, “the German approach to the war still stands out for its widespread willingness to identify the nation’s cause with God’s will, and for the spiritual exaltation that swept the country in 1914” (11). The disastrous outcome of the war had a profound impact on Germany’s pious population, including its missionaries. It exposed the pretensions of their religious and political ideologies, and injected humility into the national hubris, thus making conceivable a more appreciative view of Confucianism.

Chapter 1, “The Missionary Impulse,” is among the clearest, most succinct overviews of the nineteenth-century missionary impulse that I have come across. Were I still teaching a class on the expansion of world Christianity, I would assign this chapter.

Chapter 2, “Responding to Failure,” is an impressive summary of missionary recognition of and response to their general ineffectiveness in persuading the Chinese to change their religion. Their stress on conversion as mental assent to a system of arcane doctrines varyingly stressed across the ecclesiastical spectrum represented by Western missionaries doomed them to disappointment. Missionary notions of racial and cultural superiority, rendering Chinese converts permanently inferior and giving rise to missionary suspicion of Chinese motives, ensured that congregations would struggle and atrophy due to a permanent undersupply of worthy indigenous clergy.

Chapter 3, “Missionary Optimism,” is convincing in its portrayal of the roots and forms of Chinese resistance to foreign missionaries and their religion. I did wonder as I read the conclusion to this chapter whether “Unabated Suspicions” was the best or only way to characterize missionary attitudes toward Chinese Christian spirituality. Missionaries themselves often spoke patronizingly of their converts as children. To claim patrimony and behave responsibly as a father at the time was thought to be a good thing, an essential part of wholesome growth to maturity. The difficulty, of course, is that the day when the children could leave home and fend for themselves turned out to be a mirage . . . a constantly receding horizon that could never be reached. Some families in the West still behave this way, while in other parts of the world, children never do leave home.

Chapter 4, “A Fractured Landscape,” is a pivotal chapter in Wu’s narrative. As mentioned in my earlier comments, WWI was without doubt a fulcrum in the history of Western Christianity generally, and in the long record of Western missionary self-righteousness and notions of moral superiority, specifically. Missionaries had, of course, noted frequently with deep concern, the gulf between their nations’ “Christian” ideals and these same nations’ ruthless exploitation of weaker peoples. There is a whole body of missionary protest literature relating to the Opium wars, the Indian wars, and the bloody exploitation of Africa in the quest for slaves, ivory, rubber and diamonds. But nationalism runs deep, and missionaries were inclined to excuse such lapses in terms of Providence or judgment, or as temporary aberrations from the norm. They illustrated (as we do) the soundness of Reinhold Niebuhr’s Moral Man and Immoral Society thesis. Pride of community is a mortal sin against others rooted in personal virtue.

I was surprised that—given his elucidation of missionary hopes and expectations associated with Chinese Christian conversion—Prof. Wu made no mention of James Dennis’s encyclopedic four-volume Christian Missions and Social Progress: A Sociological Study of Foreign Missions (New York: Revell, 1897–1906), or earlier, more anecdotal books of that genre that bolstered the flagging spirits of exasperated missionaries and their supporters.

Chapter 5, “Order out of Chaos,” is another excellent chapter in which the author demonstrates the difficulty we humans have in expanding the category “we.” Wu’s elucidation of the possibilities and actualities of Volkskirche, applied both within and beyond Germany, is particularly helpful. The racial hierarchies that were a part of the accepted Western intellectual framework of the day were difficult for everyone, including Western missionaries, to transcend.

Chapter 6, “Falling in Love with Confucius.” Missionaries’ increasingly favorable views of Confucianism that eventuated in their “conversion,” such as it was, were probably the somewhat predictable outcome of their close, prolonged association with the Chinese. Etic (outside observer) and emic (inside understanding) perspectives are very different. Only the former (etic) is possible to newcomers and foreigners who remain incubated in a cultural, linguistic, and religious world that is quarantined from the Chinese; but with cultural immersion, linguistic facility, and growing misgivings about the superiority of one’s inherited worldview, the latter (emic) becomes possible, if not inevitable. German missionaries in this well-told narrative were neither the first nor the last Christian missionaries to become dismayed by the shortcomings of their own faith to the point of appropriating the views of their erstwhile nemesis! The question of missionary rejection of Buddhism is an interesting one, worthy of further understanding.

Chapter 7, “Unfulfilled Promises,” highlights the implications and practical effects of thinking internationally (SVD) rather than simply nationally (BMS). I do wonder whether the author’s use of the term suspicion is somewhat too laden with negative connotations to do justice to missionary theory and practice that might instead have been characterized as cautious. Perhaps suspicion and caution are linguistically affinal; but whereas caution gives missionaries the benefit of the doubt, suspicion does not. See my comments on chapter 3.

Chapter 8, Fruits of the Spirit, and Conclusion: Failure and Success. The last two chapters bring together the book’s several themes and resonate with my own limited experience with Chinese friends, academics and student interns over the past two decades. Between 1997–2013, I edited an international scholarly journal and directed a study center in New Haven that hosted numerous Chinese academics—often Fulbright Fellows or Yale Fellows. Some of them were Christians (Catholic and Protestant), associated with both registered and “underground” or unregistered churches. Most were not religious per se, but were curious about the relationship between religion and society, and between religion and common sense.

A personal story. One such academic had recently retired from Nanjing University’s chemistry department. He was an active member of the Communist party, served as consultant to the Red Cross Society of China Jiangsu Branch, was vice president of the Association for Yanhuang Culture of Jiangsu, and was well connected to the city’s government officials. As founding director of the Study Center of Faith and Society (Nanjing), he was also in close touch with various Muslim, Buddhist and Christian intellectuals and organizations in the city.

In late 2009 I arranged on his behalf a series or informal conversations with administrators, faculty, and students at Yale University and Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, and with similar groups in New York (New York Theological Seminary) and Boston (Boston University). Each meeting was a somewhat informal conversation—a candid sharing of opinions, really—on whether, and if so, how, religion contributed to the common good in America. Informal conversations were also arranged with members of Anglo and Chinese churches in the region—businessmen, lawyers, and various professionals—as well as with the Muslim and Buddhist chaplains and student devotees at the university. The exercise culminated with a trip to Washington, DC, where we spent three hours discussing the subject with five Chinese-speaking State Department staff members,

I was reminded of an Amharic proverb that I heard frequently as a boy growing up in Ethiopia; “slowly, slowly, an egg will move on legs” (ቀስበቀስ እንቁላል በእግሩ ይሄዳል). The meaning is clear: be patient, keep trying, and in time things will work out as they’re supposed to.

I am grateful for the invitation to read and react to the book. It has been a most satisfying education!

9.4.17 |

Response

Commentary by Justin Choi

Albert Monshan Wu paints a narrative of how the failure to Christianise China transformed Christianity in the twentieth century. Rendering this epochal transition from an overwhelmingly Western mould for Christianity was the vanishing mediator of the European Christian missions attached to competing imperialist projects. In charting this shift away from European metropolitan centres to colonial peripheries, Wu brings to the fore the changing missionary attitudes, assumptions, and institutions, the culmination of which for Roman Catholicism was the papal encyclical Maximum Illud (1919) and the national church movement for the German Lutherans leading up to the Second World War.

This densely researched account brings to light the diverse transnational actors and institutions between China and Europe, and makes a case for how the seat of authority for global Christianity shifted from Europe to elsewhere through Christian missionaries. The main contention of the book is that in China the German Protestant mission (BMS) broke away from the nineteenth-century formula that equated Christianisation with Europeanisation (12), and in so doing revolutionised European Christianity itself. This marked the turn towards opening up if not completely indigenizing the ecclesiastical governance structure, allying with the local Confucian forces previously held in high contempt. This was on account of Confucianism being increasingly “defined not as a religion, but rather a cultural force” (186), one easier to placate than threats such as secularism, communism and anti-Christian nationalisms.

Contrary to the nineteenth-century assessment which found Chinese converts and Confucianism suspect, largely owing to the earlier Jesuit attempts to present Confucianism as a “natural religion,” by the 1920s a number of factors made the European missionaries receptive to the institutionalising of indigenization and ecclesiastical self-governance. Framing this shift is what Wu cites as the growing “divergence between an increasingly secular Europe . . . and other parts of the globe where Christianity has gained fervent followers” (15) which had grown such that the European drive for the mission previously in combination of Christianity and imperialism became more ecumenical and liberal by the end of the Second World War (3–4).

Central to Wu’s narrative then is the recalibrating of the intellectual germination for the de-Europeanisation of Christianity to the pre-First World War period, rather than the post-1945, by highlighting the theological and missiological adjustments made on account of China. As such Wu’s central narrative, it should be noted, is folded along the line of the First World War rather than the Boxer Uprising or the Second World War. This structure allows Wu to synchronise the tectonic shift in Christianity (12) with the field missionaries’ efforts to “find a synthesis with other religions to survive in Europe” (15–16) by jettisoning the “exclusive salvationist claims” of Christianity (15–16).

Wu concludes by suggesting the “European encounter with China catalysed new ways of Christian thinking” (8), which Pope Benedict bemoaned as “self-secularisation” (15). Narrowly pitching secularisation as such, the book underscores how “Christian missionaries laid the foundation for the decline of their own religious authority” which caused the “rethinking internal to Christianity, advanced by Christians” (253).

At the heart of Wu’s analytic engine is the perception of failure held by the missionaries in response to which indigenisation had been taken up in the respective confessional divides—which brought about the acceptance of indigenisation, a process by which the European missions transferred their governing authority to local laity which, in turn, precipitated the drastic rescaling of the church’s scope in Europe. This is a simplification but a crucial move that links indigenisation in China and secularisation in Europe, culminating in “[renouncing] proselytization as ‘corruption of Christian witness’ and an impediment to religious freedom across the world” in 1965 (250). Out of this came the acceleration of self-secularisation, although it is unclear which kind of secularisation Wu has exactly in mind.

Leaving aside the key points, there are several points of convergence between Chinese and Korean Christianity, and the questions most likely to arise in scholars of Korean Christianity could be channelled into two: the divergent reasons for the tremendous growth of Christianity in contemporary Korea despite similar conditions, and factoring in the absence of America in Wu’s account, except as an ideological foil in his account of the other. The arc of the analysis is particularly inviting to those familiar with modern Korean religious history because, from the terms set in the book, Korea succeeded where China supposedly failed. The spectacular growth of the Christian population, the majority of whom belonged to conservative evangelical churches hostile to not only other religions but to ecumenical developments, despite being broadly in line with ecclesiastical indigenisation, calls into question some of Wu’s key contentions.

This is not to mention that the Korean liberal church leaders in the 1920s, particularly those belonging to the YMCA, registered a position nearly identical to Chen Yuan and Ling Deyuan cited in chapter 8 with regard to church governance, in response to the secular nationalists’ charges of Christian complicity with Western imperialism. In particular the indigenisation efforts were welcomed by the Japanese colonial authorities keen to weaken the Western hold over the local Christian population.

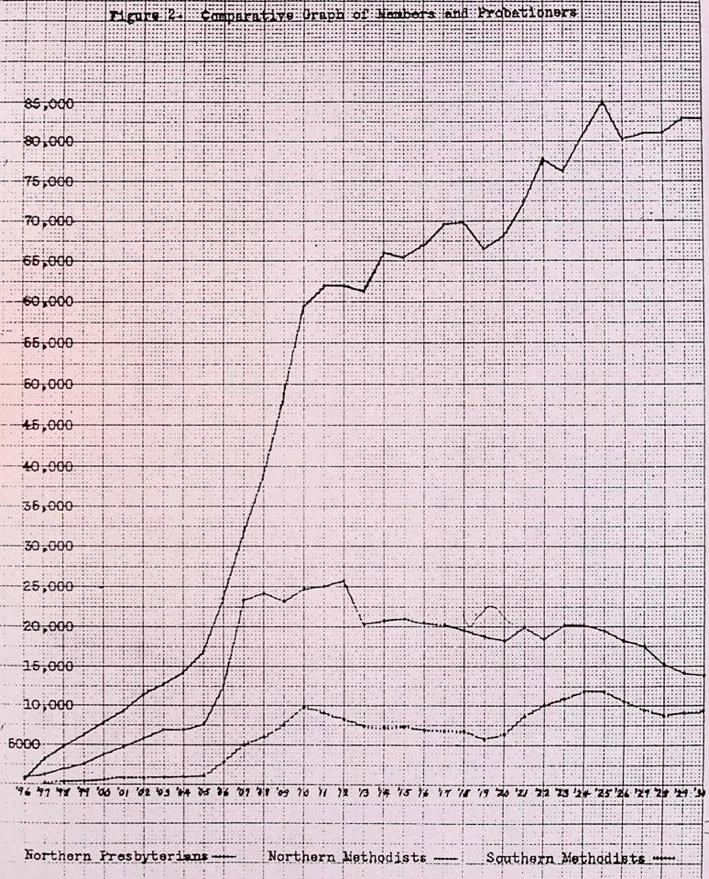

A simple figure ought to demonstrate the success of Christianity in Korea. As of 2014, the census finds 29 percent of South Koreans to be Christians, although it is very unwise to plot a steadily inclined line of growth (it was more a spurt and jump). This is not to privilege Korea over China. My general point is rather that given the nearly identical set of cultural, intellectual, and institutional challenges faced by the Christian missionaries—not to mention tremendous overlap in the personnel circulation between the two countries—the arguments of Wu appear to invite us to explain the diverging growth trend of Korean Christianity dating back to 1910, particularly given that conservative Presbyterians rose vertically while more liberal Methodists stagnated.

Fig. 1. The Growth of the Protestant Population in 1920s Korea

Therefore, in trying to apply Wu’s historical insights, it is unclear to what extent indigenisation and secularisation, as Wu describes, would explain the Korean experience. If the charges of imperialist legacy as well as scientific irrelevance diminished the intellectual and social purchase of Christianity in China (117–20), contemporary Western observers would have found it impossible not to notice the countervailing trend in colonial Korea where conservative evangelical churches grew spectacularly even as the Japanese colonial apparatus enthusiastically amplified the above claims in trying to undercut Western Christian cultural preponderance. One may reasonably cite highly contingent political contexts, including the Japanese annexation of Korea from 1910 to 1945, but the intellectual rhetoric by the Chinese thinkers sampled in the book is remarkably similar to that of the Korean Christian responses.

Had indigenisation found ideological acceptance as part of state moral apparatus by the likes of Kang Youwei (74; 225) on the one hand and the declining European financial contribution on the other, such calls could have been resisted, both institutionally, theologically, and economically by the local mission leaders (for instance, the cardinal importance of tithe and the petitions for tax exemption under the banner “religious freedom” in colonial Korea date back to this period in keeping with the American legal interpretation). Therefore, however desperate Christians may have been to dispel the charges of imperial complicity, calls for indigenisation simply invited countless references to Matthew 22:21, “unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; unto God the things that are God’s,” in an attempt to consolidate church hierarchy and improve church finances. This is not to downplay the validity of the indigenisation thesis, but to suggest that demands for indigenisation, however seemingly popular, may not have been as gripping as Wu’s chosen protagonists stressed.

This dovetails into my second point with respect to the absence of the American role in the overall analytic structure. I would like to take the opportunity of this forum to ask the author whether the core contentions concerning the transformation of global Christianity may be modified had the American innovations been brought into the picture. Indigenisation, it strikes me, does not automatically generate norms concerning the relationship between the church and its members; nor does it necessarily prescribe a strict constitutional separation between church and state to which Koreans gravitated. Seeing that the most salient trend of the Korean Christian community was the introduction of American models of religious separation in favour of the European missionary norms, governance structure, and economic ideology, I am keen to hear Wu’s reflection on this issue.

In sum Wu writes a “narrative of unintended consequences” in which Christian missionaries “transferring power to Chinese pastors” (253) caused an axial displacement in Christianity away from Europe to elsewhere. Identifying this geographic dislocation, called indigenisation, and which is closely tied to secularisation, Wu traces this back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’ mission experiences. This overall trajectory seems to be inconsistent with the tremendous expansion of Christianity witnessed in Korea at the same time, particularly the differential rate of growth enjoyed by each denomination. This observation invites new questions regarding the role of America in mediating this disparity as an intermediary between Europe and the global South.

9.11.17 |

Response

Commentary by Steven Pieragastini

Albert Wu’s From Christ to Confucius offers a glimpse at the inner workings of Christian missions in China from their (re-)establishment in the nineteenth century until their forcible expulsion in the mid-twentieth century by the successive blows of the Second World War and the Communist victory in mainland China. Few works in the growing canon of scholarship on Christianity in China deal so capably with both Catholic and Protestant missions (the Societas Verbi Divini and Berlin Missionary Society, respectively), and perhaps none does so with such a wealth of evidence directly from missionary archives. Another asset of the book is that it is truly global in scope, following missionaries from their homes in Germany, describing the forces that convinced them to become a missionary, exploring their decision to go to China (of which they generally knew very little), the circumstances of their training and arrival in the field, and the many difficulties they encountered there. Previous studies have achieved this sort of transnational scope, but few have done so for the period following the suppression of Christianity in the mid-Qing period, and those which do, such as Henrietta Harrison’s The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village (2013), Eugenio Menegon’s Ancestors, Virgins, and Friars: Christianity as a Local Religion in Late Imperial China (2010), are focused more squarely on China than Wu’s study, which devotes considerable space to developments in European Christianity. Wu examines the cultural, intellectual, and political contexts in both China and Europe which helped determine the space and form of interactions between foreign missionaries and Chinese Christians. In doing so, he demonstrates the need to investigate the history of missions in situ; this is especially important with the subjects of his study, who were increasingly constrained by developments in both Germany and China in the interwar period. A thorough understanding of the complex political environment of Republican and early People’s Republic–era China also leads Wu to, appropriately, discard an over-simplified “domination-resistance” model of church-state relations that has characterized much of the scholarship on Christianity in China.

But the greatest contribution of this book is the one indicated in the title. Wu convincingly shows that World War I was not only a severe blow to the missions’ finances and source of personnel, but perhaps more importantly, initiated a rapid psychological shift among both Western missionaries and Chinese (both Christian and non-Christian). The cultural conceit that had undergirded the entire missionary enterprise was weakened by secularism in Europe and definitively destroyed on the battlefields of the Western Front. Consequently, the condemnation of indigenous belief systems as inferior superstitions was replaced by a more accommodationist approach similar to that adopted by the first Jesuits to arrive in China in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. Similar to the early Jesuits, Christian missionaries in the post-WWI environment quickly embraced Confucianism, previously seen as the font of China’s many ills, to attack Buddhism, as well as new and threatening forces of nationalism and Communism (Wu might have also mentioned that—not coincidentally—this period also ultimately saw a “resolution” to the Rites Controversy in the Catholic Church, whereby Rome essentially conceded by interpreting ancestor worship as a “civil ceremony”). At the same time, missionaries remained loath to hand over the Church to indigenous clergy, suspecting them (with some justification) of collaborating with or at least being sympathetic to the same nationalists and leftists who denounced missionaries as mere imperialists. Combined with their wider insecurities about the failure of Christianity to take deeper root in China, along with dissatisfaction with Europe’s drift towards secularism, missionaries viewed Chinese Christians through the lens of a “hermeneutics of suspicion” (68–70) despite their newfound respect for Chinese culture.

But Wu is not content to tell a simple story of failed indigenization. He pushes back against the interpretation of missionaries as agents or tools of imperialism (the inverse of the narrative of missionaries as victims of anti-foreignism or international Communist conspiracy) and similarly is not content to view the shift from cultural arrogance to a relative degree of accommodation as merely the result of a generational shift within the missions (since some individual missionaries entirely changed their views on Chinese culture over the course of their tenure in China) or a pragmatic or cynical adaptation to modern Chinese nationalism. Missionaries emerge from Wu’s study as self-critical, sincere, and dynamic if yet constrained in most cases by a degree of disdain for Chinese culture, including Chinese Christians. Chinese Christians likewise are seen by Wu as three-dimensional figures rather than passive victims of Western imperialist designs or heroic trailblazers for indigenization. Chinese priests did challenge the cultural arrogance of European missionaries and did advocate for indigenization, in the case of the Catholic SVD missions even going over the head of the German mission leadership to appeal to the Propaganda Fide in Rome, but they also were not necessarily intent on immediately expelling and cutting ties with foreign missionaries. Particularly when it came to financial sustainability, Chinese Christians admitted their own limitations in lieu of support from abroad, even appealing, in the case of the Chinese Protestants examined in the text, to the Berlin Missionary Society all throughout the Second World War and into the postwar period, when Berlin itself was largely reduced to rubble.

Wu’s conclusions have much to recommend them as a framework for reinterpreting Christian missions in China but do arguably derive from the specific focus on German missionaries, who, aside from remarkable individuals like Karl Gutzlaff, have largely been ignored in English-language studies of Christian missions in China. This German dimension of the text leads to some fascinating passages, such as the discussion in chapter 5 on the resonance of racialist thinking among German missionaries in China (most of whom were lukewarm if not horrified by the rise of the Nazis), as well as the unique difficulties presented by the Nazis’ prohibition on foreign currency transactions, which effectively severed funding from Germany to missions in China (a problem the SVD partially evaded thanks to the international structure of the SVD and the Catholic missionary enterprise that was guided by Propaganda Fide). But it is less obvious that the reinterpretation of Confucianism by German missionaries was reflective of a wider reassessment of Chinese culture, including by the relatively more powerful French Catholic and Anglo-American Protestant missionaries. Aside from differences of denomination and nationality, the situation in China varied substantially from region to region to the extent that generalizations are nearly impossible. One could point to evidence from missions in the mid-nineteenth century, before German missionaries arrived in China, suggesting a deep respect for elements of Chinese culture, and yet one could also easily find residual cultural arrogance in the writings of missionaries expelled from China in the 1950s. It could be argued that, in the case of the Catholic Church, the issue of cultural imperialism has never effectively been resolved, and (at least from the Chinese government’s perspective) is ultimately the stumbling block which must be overcome to bring about Sino-Vatican reconciliation. David Mungello’s The Catholic Invasion of China (2015) examines this issue in great depth; though Mungello’s account is more nuanced than his title suggests, he is ultimately quite critical of missionaries in China, and the reviewer wonders how Wu would respond to his arguments.

Returning to the book at hand, even with the two mission societies examined by Wu, the picture is often muddled (as Wu phrases it, there were “threads of continuity” amid “moments of rupture,” 162). Wu’s formulation of intellectual and cultural transformations amid institutional inertia is an admirable attempt to contend with such complexity, but, as Wu himself shows, the opposite seems to be a more accurate characterization of the German leadership of the SVD mission in Shandong, which was prodded continually by Rome to embrace indigenization. It might also have been worth examining more the extent to which missionaries’ newfound respect for Confucianism was connected to trends in European Sinology and popular conceptions of China in Europe (to be fair, this is touched upon in the aforementioned discussion of race theories as well as through the character of the Sinologist and liberal Protestant missionary Richard Wilhelm).

Wu’s most provocative claims are laid out in the introduction and conclusion, when the story’s implications are extended into a reflection on the evolution of global Christianity in the twentieth century. Wu says European missionaries reluctantly but willingly embraced “self-secularization” and came to abandon the conviction that “Eurocentric versions of Christianity” (16) were the only form of Christian truth, what he calls “a sincere engagement with the world” (17). After World War II, when many missionaries returned to a war-ravaged Europe, the failure to make China and other parts of the Global South Christian led to a reassessment not only of proselytization (which was considered passé by the 1960s) but of Christianity itself in the ecumenical movement, which emphasized cross-cultural dialogue and interdenominational reconciliation (in the case of the Catholic Church, these changes were formalized through the Second Vatican Council and in the Protestant case through the World Council of Churches). In other words, the dramatic changes in global Christianity across the twentieth century were not caused by a reaction to Communism, consumerism, modern science, or other developments ostensibly inimical to Christianity, but instead the result of internal changes born in large part by the failure to rapidly Christianize the world (253). This sea change in twentieth-century Christianity has been clearly reflected in the fate of two mission societies Wu examines: the Berlin Missionswerk, which “has now essentially become a secular organization—it no longer has its own seminaries, trains its own missionaries, or engages in evangelism,” and the SVD, whose priests now primarily come from Southeast Asia (255). It is difficult to know where this interpretation leaves Christianity in China. While some Protestant denominations are now growing at a pace that missionaries a century ago could only dream of, Christianity is still understood through a prism of imperialist history, especially the Catholic Church. Is it possible that, if missionaries had more quickly adapted their thinking on Chinese culture, Christianity would not have been so closely associated with imperialism, and have set deeper roots in China before being suppressed during the Maoist period? If not, we are, along with the missionaries of the past century, still in want of an explanation for why the “foreign religion” of Christianity has faced centuries of obstacles in China whereas other originally foreign faiths (Buddhism, and to a lesser extent Islam) have become an accepted part of the fabric of Chinese culture.

9.18.17 |

Response

German Exceptionalism, Chinese Agency, and Religion and State in Modern China

In From Christ to Confucius, Albert Wu argues that German Protestant and Catholic missionaries’ encounter with Chinese Christians in the early twentieth century, combined with profound dislocations wrought by the First World War, led them to embrace dialogue with Confucianism. Having previously blamed Confucian traditions for Christianity’s underdevelopment in China, German missionaries revised and tempered their former skepticism of Chinese Christian spirituality. Though consistently condescending toward their Chinese coreligionists, and reluctant to relinquish control of church institutions, missionaries ultimately could not ignore the ground shifting beneath their feet. The rise of Communism and secularism in Europe and China prompted them to see Confucianism as a discursive ally and bulwark of traditional civilization that could help stem a more threatening tide of pernicious newness. This contingent but unmistakable change of heart, Wu argues, not only signaled a long-awaited acceptance of Christianity’s indigenization in China, but betokened the global decoupling of Christian faith from European forms that continued to unfold over the twentieth century.

I will leave the details of Christian doctrine and politics, and of Christianity’s long history in China, to my much more knowledgeable colleagues. Instead, I will comment on three interrelated themes: the German missionaries’ role as intellectual and cultural intermediaries; the question of Chinese agency; and the question of religion and state in modern China, which I will address partly by making some comparisons and connections with the history of Islam and Muslims in China.

Prof. Wu meticulously maps the conjunctures within missionary thought and international politics that opened the possibility for greater authority for Chinese clergy. In contrast to earlier accounts, Wu shows how missionaries in China were “no simple lackeys of empire” (69), but true (if originally unintended) cultural intermediaries who, at the extreme, even came to argue against imperialism as they grappled with the all-important question of indigenization.[See, for example, Joseph W. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988).[/footnote] Wu joins several scholars who have taken more nuanced approaches to missionaries in modern China and beyond.

Prof. Wu’s focus on Germans is a sound choice in this regard. German missionaries remained relatively unbeholden to imperial interests compared to their British and French counterparts. As we know, Germany lacked a colonial empire on anywhere near the scale of Britain or France, and the few territories it gained between the 1880s and 1914 were confiscated during or after the war. This fact compels us to locate some of the significance of German missionary projects outside the dynamics of imperialism. Here Wu’s account of German missionaries echoes Suzanne Marchand’s findings regarding German Orientalists. Marchand argues that German Orientalism was a largely non-hegemonic project emanating from what we are obliged to call genuine interest: originating in early-modern biblical exegesis, German Orientalism placed the spiritually rich cultures of the “East” alongside Christianity and the Greco-Roman inheritance as an underappreciated third pillar of Western civilization.

Exceptional as the Germans were, one of the most important questions raised by the book, and one that perhaps could have been taken further, is that of Chinese Christians’ agency. Prof. Wu states in the conclusion that “the German case reveals that it was not the Europeans themselves who first embraced liberalism. Rather, Chinese Christians in the 1920s were pushing German missionaries to become more liberal” (257). Still, the first six chapters trace the missionaries’ intellectual transformation using German-language sources, whereas it is primarily the last two chapters that deal with the views and actions of Chinese Christians. Of the multiple factors driving missionaries’ eventual embrace of Confucianism, which ones mattered most? Rather than missionaries’ gradual push toward indigenization, could the story instead be told starting from the perspective of the Chinese Christians pulling them? In addition to the missionaries’ internal transformation, external forces such as the First World War, the rise of secular ideologies, the rise of Nazism, and transnational church politics (for example, the BMS’s disapproval of liberal-modernist Anglo-American Protestantism, or the SVD’s increasing obligations to the Vatican and international funding) receive more treatment by Wu—and presumably more causal weight—than the pressures exerted on missionaries by the Chinese Christians. If it is still true, then, that Chinese Christian agency was the decisive factor, it would be helpful to have a more systematic summary of the leading Chinese Christian figures, as well as of their major publications and initiatives, so as to reflect that decisiveness. For example, were Ma Xiangbo and Ying Lianzhi’s critiques of the SVD’s unwillingness to appoint more Chinese clergy really a temporary “backlash” (93–94), or part of a broader and more consistent pattern of Chinese Christian pressure? How much Chinese Christian writing was devoted to such critiques?

As Prof. Wu shows in chapters 7 and 8, a reconstruction of Chinese Christian agency must also be rooted in the larger story of China’s monumental transition from empire to nation-state. Wu gives ample coverage to the effects of the 1911 revolution, the New Culture Movement, rural strife and the spread of Communism among the peasants, and the conflict with Japan escalating into war. Within this, however, I believe a more extensive consideration of the specificities of the Guomindang government and its policies toward religion, especially during the “Nanjing Decade” (1927–37), would help clarify the conditions under which Chinese Christians called for greater indigenization of church institutions.

Consideration of the Guomindang’s role first requires greater elaboration of the similarities and differences between Communist and Guomindang positions on religion. With regard to similarities, Prof. Wu mentions how the formation of the PRC in 1949 left Chinese Christians “no choice” but to forsake the missionaries and finally fully indigenize (that is, nationalize) the church. PRC-era Communist atheism, however, was not the first ideological behemoth to thrust stark choices upon Chinese religious minorities; rather, I would argue that the Han-centric nationalism of the Republican era was a similar sine qua non, an immovable object that made certain positions more tenable than others. In the wake of widespread anti-Christian attacks, indigenization for Republican-era Chinese Christians was not only a question of doctrinal purity, institutional control, or “spiritual maturity” (7)—the main preoccupations of the German missionaries—but also one of basic survival. The fall of the Qing, the emergence of Chinese nationalism, and the Guomindang’s harnessing that nationalism all had tremendous consequences for any group outside the national mainstream. In particular, as Frank Dikötter has argued, the 1911 revolution and the New Culture Movement coincided with an equation of the nation with the race.

Needless to say, there were also many differences between the Communists and the Guomindang. German missionaries, however, were not always in a position to appreciate these differences. Prof. Wu writes that the SVD perceived that “communists and nationalists . . . were united in their collective hatred of religion . . . together, these secular opponents advanced an antireligious, and moreover anti-Christian, sentiment” (173). Wu indicates that German missionaries’ paranoia about facing atheists on all fronts, and their resulting inability to distinguish between Communists and Guomindang, were informed by the situation in Weimar perhaps more than that in China itself (173). Nevertheless, Wu’s emphasis here on the missionary perspective risks blurring two important distinctions. First, the temporary phases of Guomindang-Communist alliance were tactical, and nominal “cooperation” never fully offset the overall dynamic of bitter rivalry and often open civil war between them. Second, more importantly for our purposes, the Guomindang’s evolving position toward religion hardly resembled that of the Communists. On the whole, it was less rigidly doctrinaire (though the Communists were also capable of improvisation). I would characterize it as still highly ideological in theory, but eclectic and opportunistic in practice. As Rebecca Nedostup has shown, and as Wu mentions elsewhere (89), the operative distinction for the Guomindang was that between rational “religion” and irrational “superstition.”

Chiang Kai-shek himself illustrates the Guomindang’s complex relationship with Christianity, and religion generally. As we know, Chiang remained committed to Confucian principles, but nevertheless also adopted Christianity at Song Meiling’s encouragement. Importantly, he did not see this as a contradiction. As Jay Taylor states, “Chiang found Christianity appealing because it stressed the conversion of moral thought to action and was consistent with the moral teachings of Confucius.”

A brief comparison with Islam in China may help clarify some of the above points. While general comparisons between Islam and Christianity ought to elicit skepticism (largely because our entire conceptualization of “religion” tends to be stacked in Christianity’s favor),

The major similarity lies in the pressure to make religion “Chinese.” As stated above, this pressure derived not only from Chinese Christians’ belief in the intrinsic value of Confucianism, but also from the consolidation of the Chinese nation-state. Why else, we might ask, would Chen Yuan make the same argument about Christianity’s historical Sinicization (226–44) that he made about Muslims (and other peoples)? As Prof. Wu states, “Chen argued that a strong state was founded on the acceptance and integration of foreign, disparate elements into the broader majority culture” (227). I would argue, however, that this was not merely Chen’s contribution to the indigenization of Christianity, but part of an even larger historically cast metaphor for the types of transformation the Guomindang state hoped to enact upon religious and ethnic minorities. Again, as Wu states, “Chen . . . remained a staunch Chinese nationalist from the beginning of his career to the very end . . . [arguing] for the primacy of Han culture and the necessity for foreign cultures, religions, and ideas to adapt to the more tolerant, enlightened, and benevolent structure of Chinese civilization” (243–44). Here, we should note that in the mid-1930s, Chen Yuan participated in a Chinese Muslim initiative known as the Fu’ad Library project, a Guomindang-backed project ostensibly to build a library for Arabic books given to Chinese Muslim leaders by Kings Fu’ad I and Farouq I of Egypt—but in reality, to construct Islamic knowledge with Chinese characteristics. Fifteen other carefully selected Han intellectuals and government officials participated in the library’s planning committee, among them Cai Yuanpei—who, Wu points out, had in the early 1920s supported the student organization known as the “Great Federation of Anti-Religionists.” Clearly, the Guomindang had complex and vested interests in the Sinicization of religion—strong enough even to convert former atheists.

The major difference between Islam and Christianity in China was that maintaining good relations with Christians did not offer the Guomindang state the same promise of territorial control and geopolitical boons that good relations with Muslims did. Chinese Muslims could do things the state could never accomplish on its own: namely, spreading the Guomindang’s own ideology of Sun Yatsen-ism, patriotism, and Chinese-language education on the Northwest frontiers, and conducting diplomatic outreach to Muslim countries during the war with Japan. Chinese Muslim elites undertook both of these tasks in an authentic, linguistically and culturally informed manner that the Guomindang government itself could never dream of. They did so, however, with sanction from the highest levels of that government. Chiang Kai-shek, Chen Lifu, the Chinese Muslim general Bai Chongxi, and other top officials were all deeply involved in these “patriotic” Chinese Muslim projects, and even actively encouraged Muslim intellectuals to explore “commonalities between Islamic doctrine and our Confucian traditions and Three Peoples Principles.”

I will close with two questions that not only compare, but connect Prof. Wu’s work on Chinese Christians with my own on Chinese Muslims. First, how did German missionaries view Islam in China? The general sense of fear and opportunity expressed toward Chinese Islam by other missionaries (such as the China Inland Mission), discussion in chapter 6 of the German missionaries’ antagonism toward Buddhism, and the discussion of Chen Yuan’s scholarship in chapter 8 all invite this question.

Second, was there ever any acknowledgment by the German missionaries to a Chinese audience—or assertions by the Chinese Christians—that Christianity was not originally a European religion? The growth and institutionalization of professional history as an academic discipline in China from the 1900s through the 1930s, including the translation of numerous foreign texts on ancient history and the history of religion, boosts the relevance of such a question. What, if any, was the significance of the Holy Land and of Christianity’s Middle Eastern origins to the German-Chinese encounter?

Thank you to Prof. Wu for his fascinating book. I learned a tremendous amount from it. I hope that I have raised some useful points, and that he can point out any areas where I have been mistaken.

See, for example, Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); Beth Baron, The Orphan Scandal: Christian Missionaries and the Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014); Marwa Elshakry, Reading Darwin in Arabic, 1860–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).↩

Suzanne L. Marchand, German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).↩

Frank Dikötter, The Discourse of Race in Modern China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 126–27. See also Edward J. M. Rhoads, Manchus and Han: Ethnic Identity and Political Power in Late Imperial and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000) and John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), esp. ch. 6.↩

Rebecca Nedostup, Superstitious Regimes: Religion and the Politics of Chinese Modernity (Cambridge: Harvard Asia Center, 2010).↩

ay Taylor, The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China (Cambridge: Belknap, 2009), 91.↩

Taylor, Generalissimo, 108–9. See also Arif Dirlik, “The Ideological Foundations of the New Life Movement: A Study in Counterrevolution,” Journal of Asian Studies 34/4 (August 1975): 945–80.↩

Brian Kai Hin Tsui, “China’s Forgotten Revolution: Radical Conservatism in Action, 1927–1949” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2013).↩

See especially Shahab Ahmed, What Is Islam? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), esp. ch. 3.↩

Ministry of Education Collection, Second Historical Archives of China (Nanjing) 五 (2) – 997.↩

Some discussion of SVD contact with Muslims appear in Horlemann, which Wu cites: Bianca Horlemann, “The Divine Word Missionaries in Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang, 1922–1953: A Bibliographic Note,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, third series, 19/1 (January 2009): 59–82.↩

Brian Stanley

Response

A Response to Albert Monshan Wu

Recent historical scholarship on modern Christian missions to China, as to the non-European world as a whole, has been bedeviled by two weaknesses. First, historians have written about Protestant missions to China, or less frequently about Catholic ones, but very rarely about the two together within a single monograph. Second, Anglo-American scholars have tended for obvious linguistic reasons to confine themselves to the study of British or American missions, to the general neglect of those from continental Europe. Not the least of the virtues of Albert Monshan Wu’s book is that it transcends both of these limitations at once. By selecting as his two case studies in missions to China the Protestant Berlin Missionary Society (BMS) and the Catholic Society of the Divine Word (SVD) Wu is able to illuminate both commonalties and dissimilarities across the confessional divide. By focusing on a German Protestant mission Wu is able to view the nationalistic (and in part theological) gulf in the Protestant missionary movement that opened up after 1914 from the German rather than the Anglo-American side—something that is all too rare in Anglophone scholarship. He can also demonstrate the exceptional impact that the economic and political aftermath of the First World War had on the financing of German missions through to the Nazi era. By selecting the SVD he is able to show how a German Catholic mission that became internationalized was in a better position to weather the storms of the 1920s and 1930s than its nationally-confined Protestant counterparts, though he also highlights the extent to which Catholic missionaries in China were consistently more reluctant to advance Chinese leadership than was either Benedict XV or Pius XI.

Wu has also performed a valuable service to scholarship by charting the considerable transformation in attitudes to the Confucian heritage that is evident in both the BMS and the SVD in the inter-war period. The anti-Christian movements of the 1920s, and the emergence of the Chinese Communist Party, transformed missionary evaluations of Confucianism, so that what was once dismissed as superstition now appealed as the potential foundation of a Sinicized form of Christianity that could deflect the attacks of Nationalists and Communists. An interesting footnote that could be added to Wu’s story is that since the end of the Cultural Revolution the CCP itself has gone through a similar and no less remarkable metamorphosis in its attitudes to Confucian values, which once were disregarded as premodern superstition but are today hailed as China’s distinctive cultural contribution to the construction of a harmonious world order.

These virtues of Wu’s book are indeed substantial, and must be set in the balance against the two main criticisms that I shall offer of his work.

The first is that Wu tends to allow rather too much weight to the particularities of the German domestic context in explaining the stances taken by German missionaries in China. Thus he maintains (159) that the obdurate resistance of both Protestant and Catholic missionaries to taking measurable steps to devolve power to Chinese leadership—despite the noble aspirations to indigenization of missionary leaders in Berlin and Rome—can be explained by “the unprecedented challenges” of funding and political stability that the missionary movement faced in inter-war Germany. These challenges were indeed significant and to some extent distinctive to Germany, such as the severe restrictions placed on the export of foreign currency by the Nazi regime. But financial difficulties in the supporting constituency in Europe were much more likely to advance than to retard the process of devolution to the indigenous churches of Asia. In the case of British and American mainline missions, that was undoubtedly the case when the Depression of the 1930s brought the massive territorial expansion and investment in institution building of the first twenty-five years of the century to a shuddering halt, provoking emergency programs of rapid devolution to indigenous churches. More broadly, Wu seems at times to assume that missionary paternalism is a problem that demands particular context-specific explanation. I would myself suggest—and this is not an anti-missionary point—that missionaries are by the very nature of their vocation inclined to adopt a paternalistic relationship to their converts. Missionaries tend to regard themselves, and perhaps even more to be regarded by their converts, as fathers and mothers in the faith. Wu himself recognizes this on p. 217 and rightly notes that Chinese Christian leaders during the Second Sino-Japanese War strongly resisted the withdrawal of funding and missionary personnel from Germany. That tends to suggest that paternalism is not so much a regrettable aberration that requires specific explanation but rather the default setting to which both foreign mission agencies and indigenous Christian leadership continually gravitate. Current debates about the continued and generally willing indebtedness of African Christianity to foreign aid reinforce the point, as Paul Gifford’s work suggests.

A second and related weakness in Wu’s analysis is his tendency to extrapolate too widely and confidently from his two German case studies to the missionary movement as a whole, or even to the modern history of Christianity itself. Thus he assures us on p. 252 that “Christian missionaries altered their beliefs when they encountered other religions and civilizations.” Well, some did, but many more did not. Although Wu’s book adds weight to the evidence adduced by scholars such as Lian Xi that China could convert missionaries as well as the other way round, it is far from clear that this was the majority trend. China in the 1920s and the 1930s was the home of a confident and expansive fundamentalist movement that rivaled that in the United States in the extent of its influence and volubility. The missionaries who led that movement did not react to the Chinese “other” in the way that Wu implies. He goes on to draw a similarly sweeping conclusion on the next page when he affirms that when faced with “challenges from diverse religions, cultures, and social norms, European missionaries relinquished the hierarchical control over their own congregations” (253). His own evidence suggests that on the contrary, most of them maintained a rearguard action until they were left with no alternative but to hand over power. That was precisely what the Communists alleged when they took control in 1951, and is indeed the telling accusation at the heart of the Christian Manifesto of September 1950 (220–21).

In a similar vein, Wu makes the bold claim (257) that “the German case reveals that it was not the Europeans themselves who first embraced liberalism,” but rather “Chinese Christians in the 1920s who pushed German missionaries to become more liberal.” However, in his next sentence he notes that the Chinese Christians he has in mind were in fact influenced by an American-derived liberal form of Social Gospel theology. But the ideological roots of Social Gospel liberalism are themselves to be located in German idealism and the Kingdom of God theologies of such theologians as Albrecht Ritschl. Wu makes no mention of the theological revolution in nineteenth-century German Protestantism that laid the foundations of modern higher criticism of the Bible and of the modern theology of religions. There is a complex relationship between metropolitan theological influence and the impact of the non-Western context in explaining the processes of fundamental reassessment that some missionaries underwent in the first half of the twentieth century. What Wu has shown with admirable clarity is that the German Pietists who staffed the BMS and the ultramontane sympathizers who staffed the SVD significantly moderated their theological conservatism in the face of the enormous challenges posed to their work by the political upheavals of Republican China. That conclusion is itself valid and important, but it should not be lost by being absorbed into unsubstantiated generalizations about the course of the missionary movement as a whole.

A final question that needs to be posed to Wu’s conclusions from his data is his attempt to relate his narrative to general theories about the nature of secularization. The general thesis of the book is that, by adopting more open stances to other religions, missionaries in the inter-war period somehow anticipated the trend of Europeans from the 1960s to reject the exclusive truth claims of Christianity, thereby advancing secularization. But hardly any of those missionaries who in the 1920s reconceived the relationship between Christianity and other religions abandoned their belief in the fundamental superiority of Christianity—they simply revised their previously pessimistic views of how far indigenous cultures and religions might be a stepping stone towards the truth of Christ. Wu rightly points out that missionaries “exposed their European audience to religious alternatives to Christianity” (252), but they had been doing so since the seventeenth century. What this has to do with the decline in religious attendance in post-1960s Europe is far from clear. Furthermore, his attempt to connect the theme of secularization to the devolution of power to indigenous church leaders in China does not add up. It is commonplace to posit that secularization is a process in which religious figures, institutions, and ideas experience a decline in their social authority, but precisely what is meant by the claim that by relinquishing power within their churches in China missionaries were thereby unintentionally contributing to “their own secularization” (253)? What took place in China was an internal transfer of religious authority within a set of ecclesiastical institutions from an external to an indigenous source, but that does not amount to secularization. The attempt to enforce secularization on Chinese society came during the Cultural Revolution, and of course it signally failed, provoking in its wake a revival both of Confucian values and of popular revivalist Christianity.

I would not wish to end this response on such a critical note. The research that undergirds this book is first class, and much of its analysis is highly stimulating. Wu has skillfully integrated a China narrative with a German narrative in a fashion that is still sadly unusual, and for that we are in his debt.

8.28.17 | Albert Wu

Reply

Response to Brian Stanley

I thank Professor Brian Stanley for his careful reading of my work. It is gratifying to have a scholar of his stature and influence engage with the book. I also thank Stanley for his thoughtfully critical remarks, which I hope to respond to here.

Stanley begins by criticizing me for allotting too much weight to the particularities of the German domestic context. This may have been due to the particular make-up of the missionary societies that I studied. Both the Catholic Society of the Divine Word and the Berlin Missionary Society were controlled closely by the missionaries on the home front. Siegfried Knak, the missionary director of the Berlin Missionary Society, was a notorious micromanager. He was deeply affected by the First World War and the ensuing November Revolution, and the resulting decisions that he and the missionary leadership made shaped the trajectory of the missionary societies deeply. One can find a similar story on the Catholic side, which explains my tendency to focus on the domestic situation in Europe.

Stanley reiterates an argument that I make in the book—that it was the home front, forced by financial pressures, that eventually made the final decision to indigenize. But this should not diminish the resistance that missionary leaders in Germany raised towards indigenization before 1933. It was only after 1933, with the home front’s inability to send funds abroad, that the death knell for German missions was signaled, and missionaries were forced by the political situation around them to indigenize. But missionaries had known ever since the First World War, arguably since the middle of the nineteenth century, that they needed to indigenize faster. What took them so long? I sought to explain how missionaries justified their resistance to indigenization, despite public pronouncements against their commitment to the agenda.

The argument that I advance in the book is that German missionary leaders in Europe were partly slowing down their work in China because of global comparisons. They looked at, for example, their congregations in Africa and see much healthier numbers there, more contributions, more converts, more congregants in the pews. Thus, when missionary leaders made the decision to delay, they were drawing on a series of complex inputs to make their decisions, rather than the binary Germany vs. China that Stanley suggests. But my broader attempt was to show that the home field and the mission field were not distinct, but rather in constant conversation with one another. I wanted to show that the German missionaries belonged to a global field, they were thinking globally, and they were responding to global challenges.

Stanley questions whether this line of questioning is even fruitful. By definition, Stanley proposes, missionaries are paternalistic, and “paternalism” does not need to be explained by context-specific decisions. He may be right about that. But where I disagree with Stanley is that I do not see missionary paternalism as something static or unchanging. Moreover, I am interested in the question of how paternalism ends, how it shifts, how it changes. Parents can define their relationship to children differently, particularly as they see their children change and grow. That is what I think deserves attention—the fact that the content of missionary paternalism changed over time, and the lessons that they wished their children to learn shifted as well.

Stanley suggests that the people who revised their view of Confucianism and traditional Chinese society were not the majority. Numerically, I think Stanley is right. But culturally and intellectually, it seems clear to me that a major divide was brewing, as evidenced by the “fundamentalist-modernist” debates in the 1920s and 1930s. The protracted and intense public scrutiny that these debates attracted suggest that broader changes were afoot.

Relatedly, Stanley argues that I ignore German liberals. It is true that I do not offer an in-depth account of German liberal Protestants. But this neglect stems from the fact that German missions were dominated by conservative, Pietist missionaries. There was only one liberal missionary society in a field of Pietist missionary groups. But German liberalism does loom over my narrative—I do trace how conservative German missionaries were conscious of and responding to liberal arguments. One thread that I follow throughout the book finds that German Protestants and Catholics find their positions converging with the liberals. The SVD, pushed by the Vatican, adopts a Jesuit position, while the Lutherans, by the end of the book, are not so different from their liberal counterparts.

This leads me to my argument related to missionary self-secularization, which Stanley finds unconvincing. I knew that this would be one of the more controversial claims in the book, so let me try to clarify what I mean here. Missionaries saw their efforts in China as failures. This failure led to self-reflection, thereby modifying their beliefs. When they returned to Europe, they brought a new approach towards Christianity with them. This new approach included placing Christianity in a different hierarchy with regards to other religions, a transformation directly tied to the missionary encounter with other cultures and religions.

I am not arguing that missionaries directly led to the secularization of Christianity in China. I agree with Stanley that in the case of China, secularization was more due to the political influence of the Communists. My entire chapter on Chen Yuan and Ling Deyuan, I hope, demonstrates my adherence to the idea that the greater threat to the loss of authority in China resulted from these Communist and secular challenges.

Where does indigenization fit into this schema? My argument is not that indigenization equals secularization. I agree with Stanley that indigenization can be understood primarily as an internal transfer of power. Ideally, of course, this internal transfer of power occurs smoothly. However, my argument is that the process of indigenization was an incredibly fraught and traumatic process for all parties involved. The transfer of power to the indigenous churches in the 1930s and 1940s also meant cutting off resources, people. This dealt an incredible blow to the authority of the church. Chinese Christians felt abandoned by their previous missionary leaders. When the missionaries left China—certainly, forced out by China—the people they left behind felt abandoned. The links were cut. In a stable political situation, perhaps the indigenous churches set up in the 1930s could have thrived. But faced with a hostile and increasingly powerful adversary in the Communist state, the indigenous churches were decimated. A minority refused to parlay with the Chinese state. But the majority did. This entire process undermined the status and legitimacy of foreign missionaries, as well as the entire history of the missionary enterprise in China.

Moreover, the process of indigenization was not just one of incorporating new members into the society, of making the structures of the church more plural and more diverse. In China, the process of indigenization meant exposing Christianity to alliances with other religions, even ones—like Confucianism—that they had previously declared as the enemy. These alliances opened the door to the possibility that Christianity would be interpreted in Europe as one that was no longer the sole path to salvation. Again, I am not arguing that there is a simple, direct path of causation here. The story of secularization is a highly complex and difficult one, and as I point out in the book, the linkages between self-secularization, globalization, and the missionary experience requires future investigation.

What I would like to suggest is that as I did research for the book, I found case after case of missionaries in the 1920s and 1930s reflecting on their failures, rethinking their tactics, and modifying their ideas about how to do missionary work in China. How do we square these experiences with the broader historical processes that were to come?

I am open to the possibility that I have overstated my case and that there is no linkage between the experiences of missionaries in the 1920s and 1930s and the post-war experience. But I think to suggest that these are two completely unrelated stories would also be to miss some crucial linkages; it misses the experiences of the missionaries themselves. Many missionaries were deeply disappointed by their experiences abroad, and came home with modified beliefs, no longer completely convinced of the inherent superiority of Christianity.

Thus, when I use the term self-secularization here, I employ it in a positive sense. Missionaries, once the most belligerent, intolerant group of believers in the nineteenth century, were now open to the world in different ways, content to think about their position to the rest of the world in different ways as well. To discount these transformations, I would argue, would do a disservice to experiences of many missionaries who lived and worked in China. My goal was to try to capture those stories and understand them within the context of the tumultuous transformations of global Christianity in the first half of the twentieth century.

I once again thank Brian Stanley for so generously engaging with my work. I hope I have answered some of his questions, and look forward to advancing further dialogue and discussion.