Beyond Apathy

By

9.25.17 |

Symposium Introduction

I was listening to my local public radio station during the Republican primaries one day and I caught a segment where the host was complaining about the tone of the Republican debates. He said it was offensive, disgusting, and a shame to our democratic process. Not only were the candidates calling each other names, he said, they were also interrupting each other, yelling, and even using expletives. In my few years of listening to the show, I had never heard the host sound so angry and offended.

I sat in my office rather perplexed. I wanted to call in and ask, “During all the policy debates between Republicans it was their tone that pissed you off the most?” With talks of who could build the bigger wall, cut more taxes for the wealthy, build more prisons, and threaten the survival of more countries, the really offensive part, apparently, was the candidates’ tone. It wasn’t capitalism or the border patrol or the Pentagon that was violent. It was the way the candidates were speaking to each other. Little hope could be found on the opposing side, of course, as the Democratic party leaders rallied behind a candidate who wished to continue Barack Obama’s legacy of befriending bankers, allowing police officers to get away with murder, deporting scores of undocumented immigrants, and dropping tens of thousands of bombs in Muslim countries. As the perceptive bumper sticker states, “Vote Democrat for more sensitive imperialism.”

I was initially drawn to Elisabeth Vasko’s book Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders since the back cover promised “resources for Christians in a violent world.” As I read her work for the first time, what struck me as both refreshing and profound was Vasko’s attention to the many forms of violence that often remain invisible. “Violence does not always have visible wounds and complicity does not always entail wielding a weapon or physical assault,” Vasko writes. “Violence impacts everyone and leaves very few spaces of innocence” (4).

Vasko’s words reminded me of a talk Saidiya Hartman gave where she explains how certain “forms of structural violence,” even if we cannot always “see” it, “continue to make large sectors of the population vulnerable to premature death, not as the result of frontal assault, or war, or anarchic violence but as the slow and enduring violence that allows people to die every day from poverty, neglect, incarceration, and extreme forms of exploitation and social marginality.” “To some,” Hartman concludes, “this might appear to be violence without an agent or fail to register as violence at all, but it produces a regular death toll.”

Beyond Apathy argues that the many forms of violence experienced today are “tied to the tacit (and sometimes overt) acceptance of cultural norms that allow for the denigration of entire groups of people” (3). Vasko observes that Christians occupying various sites of political and social privilege “have been bystanders to violence,” and that their apathy needs to “be interrogated in view of patterns of social conditioning that support and even reward indifference to suffering” (9–10). Vasko is very intentional as to why she chooses the category of bystander, arguing that the term “works to disrupt victim-perpetrator and oppressor-oppressed binaries and the hierarchal dualisms often accompanying it: good/evil, innocence/guilt, men/women, white/nonwhites, God/creation, mind/body—to name a few.” “Hierarchical dualisms,” she continues, “have played a pivotal role in theological justification of hegemony” (14). Throughout her work, Vasko remains committed to the idea that true social change must involve changing the way we think about each other and organizing collectively to dismantle systems of oppression. The aim of “disrupting indifference,” she writes, “requires the transformation of individuals and social structures” (10).

We are honored to have five scholars engage Vasko in fruitful conversation. In his essay to kick off the symposium, George Yancy describes Beyond Apathy as a “weighty gift,” but “a gift that leaves all of us ruptured at the very core of who we say we are as Christians.” He writes of his indebtedness to Vasko for helping him theorize and rethink what he calls a “radical relational ontology: a body with no edges.” What Beyond Apathy offers us, Yancy says, is a book that demonstrates this radical relational ontology—“the fact that we have no edges”—by refusing “to cover over the violence, pain, and suffering that we cause others—even if it is unintentional and unconscious.” Rebecca Todd Peters praises Vasco’s critique of white anti-racist work for too often seeing itself “as part of the solution rather than part of the problem.” Claiming that privileged white people don’t get points for just showing up, Peters invites readers to heed Vasco’s call to become attuned not just to the “overt acts of violence in our world,” but to “the everyday acts of implicit prejudice and discrimination by white people.” Christine Hong notes that Vasko’s book, despite being written prior to the 2016 general election, is a timely and “essential read.” Hong reads Vasko as stressing the importance of directing compassion not just “towards others but towards the self that is learning to move beyond apathy and after that, beyond a paralyzing guilt.” In the process, Hong wonders what it might look like to prevent such deep listening and compassionate silence from drowning out “swift and courageous action within one’s own community of privilege.” In other words, “targeted communities and those under attack by their own government,” Hong writes, “do not have the leisure of waiting for privileged people to move beyond their acts of contemplative listening and learning.”

Nikia Smith Robert credits Vasko for refusing to place “the onus of reconciliation as an unwanted burden imposed upon the backs of the oppressed” yet raises questions about her discussions of white guilt and solidarity. Robert not only argues that it is sometimes warranted to shame the oppressor, but she also asks why, in instances of horrific violence, white guilt should even be a priority of ours. “Reconciliation should happen whether white people feel good or guilty,” Robert writes. “This is the essence of accountability.” In another provocative response to Vasko’s book, Jeanine Viau uses Justin Torres’s commentary on the Pulse Nightclub shooting to question the limitations of Vasko’s argument. “Curing apathy is insufficient to bring about a livable world for those living irregular lives,” Viau contends. “This will require active dissent and not just a reordering of those most esteemed values of chastity and mercy.”

In an article written in the New Inquiry, Mariame Kaba invites us to adopt what she coins the “practice of abolitionist care.” “Defense campaigns for criminalized survivors of violence like Bresha Meadows and Marissa Alexander,” she argues, “are an important part of a larger abolitionist project. Some might suggest that it is a mistake to focus on freeing individuals when all prisons need to be dismantled. The problem with this argument is that it tends to render the people currently in prison as invisible, and thus disposable, while we are organizing towards an abolitionist future.”

I read Elisabeth Vasko’s book as an exemplary and essential resource for Christians wanting to participate in this practice of abolitionist care. For years I’ve taken a counterproductive approach to addressing my students’ apathy in the classroom. I always thought that taking them beyond apathy meant taking them to a place where they cared about issues, but nothing more. By doing this, I only reinforced the violence that comes with abstractions. Vasko’s book hit me hard. Even to this day, when I still fail countless times to get my students to care, her work reminds me that what lies beyond apathy is not care about things, or even care for people. Rather, it involves practices of care—of deep listening, public advocacy, and what she calls “eucharistic solidarity.” As Vasko explains, to move beyond apathy means finding “new ways of sitting with pain, of embracing vulnerability, if we are going to participate in the healing of the world.”

My hope is that the rich conversations around Vasko’s book move more Christians to engage in the practice of abolitionist care, which according to Kaba, “underscores that our fates are intertwined and our liberation is interconnected.”

Hartman, “Slavery, Human Rights, and Personhood,” presented at Human Rights and the Humanities, National Humanities Center, March 20, 2014.↩

Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).↩

Mariame Kaba, “Free Us All: Participatory Defense Campaigns as Abolitionist Organizing,” New Inquiry, May 8, 2017, https://thenewinquiry.com/free-us-all.↩

Vasko, 67.↩

Kaba, “Free Us All.”↩

Hartman, Saidiya, “Introduction to In the Wake: A Salon in Honor of Christina Sharpe,” presented at Barnard Center for Research on Women, March 20, 2017.↩

10.2.17 |

Rethinking White Anti-Racism Work

Election night 2016 found me sitting in my sun room with my two daughters eagerly awaiting the results. I had proudly worn my pantsuit to work, joined Pantsuit Nation on Facebook, and bounded through the day with the utter confidence and hubris that surely presaged the despair to follow.

While I had voted for Bernie in the primaries, it was largely because I knew Hilary would win the nomination. As a democratic-socialist I figured Bernie offered my once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to vote for someone who truly shared by political orientation. My oldest daughter had been an ardent Bernie supporter—attending rallies, canvassing neighborhoods, and staffing phone banks to bring out the vote. I was impressed with her passion and commitment to the clear values of social justice that Bernie’s economic policies represented and her to political participation and activism at the age of seventeen when she wasn’t even going to be able to vote in the election.

My youngest daughter, on the other hand, was all-in for Hilary from the beginning. At eleven, she is a strident feminist and human-rights activist who enjoys a good political rally just as much as the next person. In the 2014 election, at the age of eight, she regularly schooled her grandmother’s friends in why they should vote for Kay Hagan over Thom Tillis in the NC Senate election (and it wasn’t because Hagan is a woman). During the 2016 election she was very excited about the possibility of the first female president of the United States.

Flash back to election night.

Like so many feminists across the country—there we were, three white, privileged females, sitting down together in front the TV prepared for an evening of celebration!

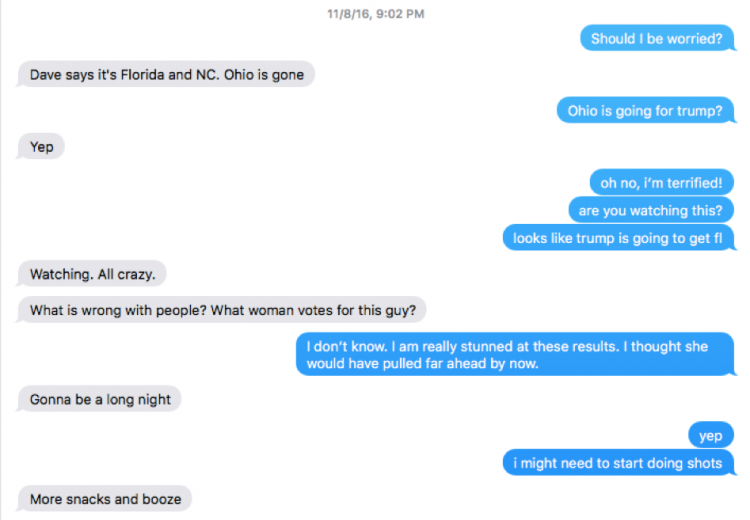

And then, the election results started to roll in. Our enthusiasm began to waver. We kept thinking it was going to be ok. About nine o’clock, I texted my best friend in DC. She is white and privileged, like us. She runs a women’s shelter, her husband works for a union and had been canvassing in Ohio and Michigan for the six weeks prior to the election.

Minute by minute, hour by hour, with millions of people across the country I watched the returns with my daughters and felt as if I had been punched in the stomach. Repeatedly. With each new state that went for Trump, it was another blow to the gut.

Across the country, people had voted to elect a president who represented everything I had dedicated my life to fighting. But he wasn’t racist, sexist, and classist in the sort of complicit and culpable way that Elisabeth Vasko so aptly describes in her book Beyond Apathy. Trump was no bystander, he actively employed race baiting tactics to tap into white people’s deep-seated racial anxiety and economic insecurities. He bragged about personal acts of sexual violence and aggression and white people across the country didn’t seem to care. Trump was the bully and white people across the country voted for him anyway. What was happening?

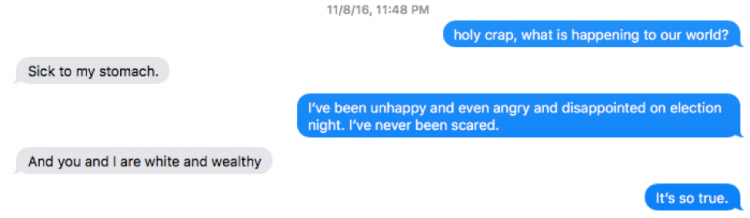

Just before midnight, I texted my best friend in DC again.

As a feminist social ethicist, my entire professional life has been devoted to fighting oppression, inequality, and injustice. I teach about racism, sexism, classism, heteronormativity and homophobia, ableism, gender binaries, climate change, poverty and inequality. As a scholar, I employ an intersectional analysis to analyze economic globalization and neoliberal capitalism and abortion and reproductive rights issues as I seek to contribute to the process of social change in our world. I am not a bystander.

But Election Night 2016 was an epiphany for me. My eyes were opened to the profound danger of what happens when progressives measure success by simple majorities. Too many progressives, myself included, had gotten comfortable dismissing the racism, xenophobia, and misogyny of too many regular people—rural folks, “red-necks,” “heritage not hate” people, the white working class—from a place of moral superiority that “our side” has won the day. Given the legitimate progress we have made as a nation on civil rights, gay rights, women’s rights, disability rights—it is easy to relax and focus on how far we have come in the last fifty years. But, a majority of the popular vote was not enough. Despite our progress, too many white people in this country continue to live and work in relative racial isolation. While the election results seem to imply that real progress has been made on a variety of progressive issues in urban areas—white, middle America struck back with a vengeance.

And, yes, I have heard the voices of black people across the country who have said to white people, “Oh, really? You are surprised by this? We could have told you that the fight is never over. The hatred and fear of whites can always be counted on to sow havoc and destruction.” The SNL skit featuring Dave Chapelle and Chris Rock skewering the naivete of white, progressive US Americans was so hilarious and spot on that I laughed so hard, I cried.

For twenty-five years, I have been a scholar-activist engaged in anti-racist work out of my commitment to the social justice tradition Vasko so aptly represents. So, my epiphany on election night was not the epiphany of SNL’s Cecily Strong, “Oh my God, I think America is racist!” I knew that.

My epiphany was that the people across the country who had elected Trump were my people. Across the country—from disaffected working-class whites to evangelical Christians, to the wealthy elite, to majorities of white women across the board—it was white people who elected Trump. While Trump may be a demagogue and a narcissistic bully, what I realized on election night was that Trump was not the problem. Trump will come and go (hopefully sooner rather than later) but focusing on Trump as the problem diverts our attention from white people across the country who found voting for this man and all he represents acceptable.

Vasko’s task of developing a theology for bystanders that prompts people to act is enormously important and there is clear relevance and value of her work for helping white Christians (and others) to think about the danger and violence in the complicity of bystanders, literally, people who stand by and watch, in the violence and racism of contemporary culture. As this is not a book review, I will simply encourage people to read the book for themselves and to use it in their own anti-racist, anti-violence work of social justice.

My interest in this essay is in turning Vasko’s analysis on those of us who do not consider ourselves bystanders and looking for a deeper critique of white anti-racist work, work which I count myself to be a part of. Too often, I fear, people engaged in white anti-racist work see ourselves as part of the solution rather than part of the problem. No doubt that part of the desire to move beyond white guilt and shame and into the activism that Vasko calls us to is motivated by a desire to be part of the solution.

Flash back to Election Night 2016 again.

When I bring Vasko’s critical lens to my epiphany—to my realization that as a white person, a white scholar, a white Christian—I am accountable for the racism of white people in this country, I find myself being convicted of being a bystander. I am not a bystander to the oppression of marginalized and minoritized communities (which is largely Vasko’s concern) but to the deep and abiding persistence and insidiousness of the racism, misogyny, homophobia, and ableism that continue to fester and thrive in the heart of white US America.

As much as I may want to claim to be “woke” because I read and teach, study and write about the history and practice of racism in this country; as much as I actively engage in the work of anti-racism personally and professionally; as much as my thought and knowledge is shaped and formed by the intellectual history and wisdom of centuries of black writers and scholars—I am not “woke” but merely on guard. To be on guard one must actively and consciously work on a daily basis to identify and analyze the racial dynamics of what is happening in our world.

One thing I have learned to recognize and embrace from philosopher and race theorist George Yancy and other black intellectuals and friends is that I am racist and that everyday, I have to actively work to fight against the racism and prejudice that lives inside me as well as the racism and prejudice that marks our world. As a white Southern woman, raised by white Southern parents, who can trace my ancestors on both sides back to the Revolutionary War, my mind, my heart, and my psyche have been shaped in unknown and unknowable ways by the white privilege of my life, my history, and my experience. I know for certain that at least one of my father’s relatives owned at least one slave. The newspaper article I found in my father’s papers after his death confirmed a long-held suspicion. I do not know for certain if there were more ancestors with more slaves but it is likely.

Privileged white people do not get points for being on guard. Privileged white people do not get points for showing up at Black Lives Matter rallies. Privileged white people do not get points for raising our children to be anti-racist or for having black friends or for working for racial justice. There are no points for being an ally. Just as there are no points for being decent, for living faithfully, for doing justice.

In Vasko’s language, my sin has been the sin of apathy. As she says, “to be apathetic is to lack compassion.” (10) Too often, I have lacked compassion for those who are actively racist or sexist or homophobia. To try to understand someone’s racism or sexism feels too much like granting moral equivalence to our positions, it skirts on the edges of a moral relativism that makes me squirm. Since the election, I increasingly find myself talking with white faculty colleagues about how to engage and understand the white racism of our students, our family members, and our communities without either alienating them or normalizing their position as reasonable and debatable.

While I believe that we are right (Vasko, Yancy and others engaged in anti-racist work) in denouncing racism (and oppression, bystanderism, apathy, etc.) as sin—it is hard to engage, say Trump supporters, if my starting point is that they are the oppressor. Avoidance of uncomfortable topics is a classic white strategy of what Vasko calls “white denial,” “not knowing,” (80) and “white silence,” (85) in her chapter on white privilege (chapter 2). While Vasko is describing how whites use these strategies to maintain white people’s distance from meaningful knowledge of racial oppression, too often, whites use these same strategies to keep the peace within white families and white communities.

For years, my white students have lamented that they do not know how to talk with their families about the issues of social injustice that they learn about in my classroom. They are nervous about what they will say to their uncle or their cousin or their mother or father when they are home for Thanksgiving dinner and discussions of welfare programs or crime are laced with racist assumptions and attitudes. Just like white people can choose to “opt out of participation in the lives of people who are different from me” (131), we can also “opt out” of difficult conversations about prejudice, race, misogyny, heteronormativity by changing the subject, excusing ourselves from the table, or simply keeping quiet.

While Beyond Apathy is focused on addressing the problem of bystander complicity in violence, I found deep insight in her work for helping me think about the task of white anti-racism. Vasko’s framing of the “bystander problem” can be used to identify ways in which white people’s bystander problem is not only about disrupting overt acts of violence in our world (bullying, rape, harassment) but also about recognizing the violence inherent in the everyday acts of implicit prejudice and discrimination by white people.

Vasko’s book ends with the wisdom that “as privileged bystanders, we have the responsibility to find ways to respectfully join others in solidarity on this journey” (245). In my book Solidarity Ethics I say much the same thing and outline steps that Vasko’s privileged bystanders might take as they move toward building relationships of solidarity with people across lines of difference.

What I did not do in that book and what Vasko’s book helps me to think about more critically is the ways in which lines of difference have been built up within the white community—dividing and separating families, communities, churches, and geographic regions from one another over the most important social and moral questions of our day. Even as we pretend not to be separated by continuing to engage in small talk, lunches, shared hobbies or book clubs by avoiding talking about those very differences that bear witness to the moral fabric of our country.

I share Vasko’s commitment to finding hope. Despite the election, despite the rise of hate crimes and violence, despite the despair I sometimes feel creeping in through the back door—I do see glimpses of hope in many places. I find hope in the six white churches in rural Alamance County that just finished a six-week series that I co-taught on “Practicing Solidarity: An Anti-Racist Seminar for White Christians.” I find hope in the fact that twenty faculty and staff at my university stepped forward to voluntarily organize and teach a semester-long course last spring titled “Refusing to Wait: Intellectual and Practical Resources in Troubling Times” as a response to the election. I find hope in the increased awareness of white people across the country that we need to step up and do something more and different than we have been doing in the past. I find hope in my daughters’ activism and the passion and commitment of white young people to stand as allies with their friends who are marginalized by HB2 in NC or threatened with deportation or simply harassed for being black or brown.

No doubt, Beyond Apathy is a helpful resource for white Christian communities that can help us live into hope.

10.9.17 |

A Response to Elisabeth Vasko

Since November of 2016, I have learned to describe the feeling in the air, the tone and tenor of the atmosphere, as BT and AT; before Trump and after Trump. Elizabeth Vasko’s Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders is a theological manual for people of privilege who live with an intentional theological grounding in the AT era.

This tenuous and dangerous reality of the AT era is not new for some of us in minoritized communities. November 9 was in many ways just another Wednesday in an already hostile America. The experience of waking up black and brown, queer, Muslim, and/or undocumented and all the intersections in between was, as always, the experience of consistent and violent erasure. What had changed in the air was the quality of what was already a virulent mean-spiritedness. This mean-spiritedness was no longer codified, subtle, or clothed in political correctness, there was no longer anything micro about the aggressions of white supremacists and white evangelicals. As a nation we regressed into a vigorously public and exacerbated meanness of character. In the face of the cruelty of this new regime, the theologies of communities of faith were challenged and pressed to swift actualization and embodiment. What we have witnessed thus far has been both the courage and tenacity of many and also what Elizabeth Vasko describes as the apathy and willful ignorance of others.

Vasko’s book is neither for folks who identify with the underside of this experience of cruelty, nor is it for the already courageous advocates and allies among us. Vasko writes for an audience that has willingly and intentionally claimed ignorance of the painful histories of people of color and other minoritized people in the United States and around the world. Though Vasko was writing prior to the 2016 presidential election, her book is an essential read for those for whom willful ignorance has been an acceptable veil or shroud of comfort and safety and the rapid re-normalization of racialized and other forms of violence in this new United States of America. She writes for privileged communities of the religious and faithful who shudder and claim, “not all ______!” when the call of “Black Lives Matter” invades their sanctuary of “safe space.” She writes for those in places of privilege who presume the labor of minoritized people in order to advance their knowledge of systems of oppressions. People who then operationalize that knowledge to further their own justice agendas without the input and cooperation of directly affected peoples. Vasko’s work is along the lines of work of other white scholars that intentionally tackle and engage the insidious nature of white supremacy and Christian hegemony, its ensuing frameworks of white privilege, and the general feeling of apathy towards what is happening in our shared world. Three themes emerge from Vasko’s text to various degrees of engagement: labor, the complexities of dismantling binaries, and courage and compassion as antidote.

Labor

Vasko reminds us that the structures and systems of white supremacy “are embedded in our psyche: in our interpretation of the world, of what is good and just” (26). This statement is true for both dominant culture and minoritized people. Each of us has internalized the insidious quality of white supremacy, Christian supremacy, and other dominant culture narratives into our lives. For people of color and otherwise minoritized people, our bodies, minds, and even our spiritualties and theologies are domesticated and disciplined to the dominant cultures of normativity, hegemony, and orderliness. Some of us consciously allow for this domestication and disciplining, if simply in order to survive. We take on Anglo names that are easy to pronounce, learn to subvert and suppress our mother tongues, our minds, and our cultural inclinations, all so that we are not seen as foreign or a threat, so that we will not alarm the dominant culture and so that it will allow us to survive. For people of color in the Academy and in the Church, we double-down; we learn the narratives, histories, and theologies of Europeans and White Americans as well as our own. We learn how to operationalize the theological labor of our people in ways that invites conversation with dominant culture narratives but does not dislodge it, all in hopes of being heard and valued at a multiply-hegemonic table. For minoritized people, this additional labor of operationalizing a psyche that we know exists to methodically erase us in order to survive, is exhausting. We all labor under the auspices of hegemonies and all suffer under the apathy of those in privileged places, but our labor is disproportionate to one another. The knowledge of this disproportionate labor is the first step to the equitable work against apathy and bystanding that Vasko seeks to envision in her text.

Dismantling Binaries

As theologians, we ingratiate ourselves to binaries, good and evil, heaven and earth, sin and guilt, man and women, white and black. Vasko’s work functions from a place that challenges her readers to complicate the binaries we serve. She asserts that white apathy is formed out of a Christian theological binary, “classical Christian atonement tradition . . . to reinforce patterns of white dominance within contemporary American contexts, but also makes it difficult to love living bodies” (73). To push Vasko’s idea further, when functioning from a place of binaries in our activism and justice work, these dualistic patterns do not only make it difficult to love actual people but it can make it impossible to even see actual bodies and actual lives. Vasko calls this the ambiguity of sin and grace (146). We cannot know fully how grace emerges from spaces of human suffering and accepting this unknowable quality of God’s grace helps us move away from our inclination to understand lived experiences of injustice in dualistic terms.

Remaining stuck in binary modes invisibilizes entire communities of people, yet our affinity for dualism is engrained in our theologies of justice. We theologians must therefore commit ourselves not only to the nitty-gritty work of complicating binaries, but also to the task of challenging the dominant culture’s expectation that minoritized people should do this labor on behalf of everyone.

The danger of white supremacy, Christian hegemony, and hetero-normativity is that they can also function within models of justice making. These dominant narratives can facilitate the picking and choosing of which oppressions to center and which to performatively liberate. As privileged people become aware of their willful ignorance and emerge from their apathy, are they truly working to dismantle the binaries that continually suppress and silence or are they simply learning different modalities of dominance? This time in different arenas and with a different vocabulary? For instance, are the narratives around racial justice one of only black and white injustices or are the stories of Latinx, Asian Americans, and First Nations people and the complexities their experiences and histories bring in conversation with one another, included?

Courage and Compassion as Antidote to Apathy

Vasko calls for intentional silence and deep listening as an act of participation in moving beyond a dangerous apathy in the lives of the privileged. As a person of color, I have witnessed this good and well-intentioned silence and deep listening from allies, particularly in the era of this new administration. This silence and listening is indeed significant in understanding one’s own privilege within white supremacist, Christian hegemonic, hetero-patriarchal systems. Such a posture allows spaces for the stories of others to seep into our consciousness and alter our behaviors in response to what we hear and learn. It is an act of compassion, not only towards others but towards the self that is learning to move beyond apathy and after that, beyond a paralyzing guilt.

However, I have found that well-intentioned silence and listening, though a critical first step, is not enough to move the arm of justice forward. In the urgent times in which we find ourselves today, swift and courageous action within one’s own community of privilege is what is needed alongside the work of compassionate silence and listening alongside minoritized communities. Targeted communities and those under attack by their own government do not have the leisure of waiting for privileged people to move beyond their acts of contemplative listening and learning. They do not have the capacity to undergo the emotional and intellectual labor of retelling their stories, undergoing perpetual re-traumatization, while simultaneously experiencing surveillance, deportation, and decimation of their human rights. What is needed is a deep listening that goes hand in hand with courageous and swift action within the most difficult spaces of privilege. For instance, what is needed are white liberal Christians doing the difficult and painful work of connecting with white evangelicals, people who find more affinity with a billionaire who has no understanding or care for the white working poor than with the human dignity of black and brown people. What is needed is for people of privilege to work out their faith for the sake of cooperative justice work in the spaces that terrify them most. It is this type of ally-ship that begins to turn the tables and shift the conversation forward. It is painful work but it is the type of pain that works to create connectional realities and theologies for the wholeness of all people. As Vasko says, “Privileged pain is not the same as the pain of those who have suffered at the hands of injustice, but these two realities are related. Understanding this relation is what helps us to begin the work of naming redemption anew” (114). Today, when I hear of privileged communities, any privileged community, intentionally engaging in the deep work of listening, I ask, what will you do with what you hear? When will do that work that is being asked of you, because the time is now.

Accountability is what sustains our mutual work towards the evisceration of dangerous apathy and towards a new theology of action for those who were once bystanders. As accountable persons we ask, to which communities are our theologies of justice accountable? Which communities do our theologies, enacted, affect? Vasko’s seminal work argues that part of emerging from apathy and bystanding in the face of injustice is to become aware of the connectional and accountable quality of our lived experiences of injustice and justice. Privileged communities are accountable for their apathy to minoritized and oppressed communities. The challenge Vasko shares with her reader is not one of suddenly waking up from apathy but intentionally moving beyond it into subversive qualities of action within one’s own communities of privilege and power, “into compassionate spaces of witnessing” (195). An active witnessing that occurs not out of a privileged and paternalistic motivation to assuage guilt but out of a deep, authentic, and urgent desire to work out one’s faith on this side of the kin-dom for the mutual liberation of all.

10.16.17 |

Response to Elisabeth Vasko

Exposition

Elizabeth Vasko, in Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders, critically examines violence top-down through the gaze of the oppressor. With liberating motivations, she draws upon the works of several liberationist, feminist and womanist thinkers to uniquely unmask the social evils of bystanders—mainly those privileged people who complicity witness violence and do nothing in their power to end structural oppression. Vasko states, “I write this book as a privileged person and am primarily concerned about bystanders who ‘enjoy more dominance than [they] suffer subordination’ by virtue of their race, class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender” (7). Important for her analysis, Vasko is a white person speaking specifically to white people about the dangers of white privilege. While this is a refreshing perspective, it is not for everyone—presumably not for me, a Black woman. Nonetheless, Beyond Apathy is a noble and necessary task because too often the onus of reconciliation is an unwanted burden imposed upon the backs of the oppressed. The deeper work of justice, however, must penetrate the circles of the oppressor. This does not happen from the outside but from within. Thus, a theological conversation from white people to white people about white privilege is a hopeful endeavor. To this end, Vasko bravely leads the charge to “ambush” complicity and go beyond apathy to dis-ease and dis-comfort while making room for grace and redemption in the kin-dom of God.

Analysis

“How can a group of well-intentioned, and sometimes, socially aware individuals repeatedly bypass opportunities for resisting violence?” (9). The weight of this question bares significant witness to the dangers of escapism and the normalization of violence. In response, Vasko suggests that escapism from authentic relationships with ourselves, with God and with another result in social and theological indifferences to suffering. She asserts, “We tend to engage in a politics of distraction” (32). Subsequently, “we risk becoming immune to violence happening in our midst” (32–33).

Vasko’s interrogation of escapism coupled with a politics of distraction is particularly pertinent for the current political climate in the United States. More pointedly, in a forsaken era of “Trumpism” many privileged persons, purveyors of power and pusillanimous perpetrators have been emboldened by hatred and hegemony. If it is even possible to consider that America could be any more sadistic, post the 2016 presidential election the normalization of violence has seemingly worsened. Trump’s overt demagogical motives through a dangerous hubristic cocktail of bigotry and narcissism has unveiled an otherwise hidden hate. It has enabled the vilest vitriol, vehemence and violence from villainous (not all) white people. Subsequent to the conspicuity of cankerous conservatives, a blooming bystander culture has gone unconcealed. This is to say, the more overt the racial imagination of America in an Era of Trumpism, the more people watch and remain silent out of fear (sometimes) but more overwhelmingly out of an indifference to other people’s suffering.

In my own neighborhood, for example, against the backdrop of a mountainous landscape dotted with white soccer-moms driving minivans and blue-collar men driving pickup trucks with decals reading: “Make America Great Again. Trump 2016,” there have been recent reports of hate crimes. Homes have been vandalized. One house’s white garage door, in particular, was defaced with a red spray-painted swastika and an additional paper taped to the wall with red ink reading, “Mixed race breeding. Keep your spick children off our property or there will be consequences.” The history of where I live is dark and delves deeply into the ugliest sins of America. I am raising womanish girls and a native son in a place once known as a sundown town, headquarters of the American Nazi Party and home to the Grand Cyclops of the Ku Klux Klan. Then, hate was hooded to cape white supremacy. Eventually, uniforms covertly legalized bigotry. Now, social evils are completely unmasked. Previously, this history was relatively dormant and inconspicuous, now it is ever more pronounced and visible. Unfortunately, this ethos of escapism that has emboldened white privileged and enabled bystanders is not just apparent in my suburb, but it pervades America.

For example, the recent United Airline debacle demonstrates the relationship between violence and a bystander culture. Recently, viral videos on social media showed a full aircraft of witnesses sitting in their seats watching authorities drag an Asian man from a flight in Chicago because he refused to give up his paid seat to a crew member. Many recorded the violent encounter with their phones but no one intervened or stopped it. Another incident was when a man-scorned known as the “Facebook Murderer” killed an innocent unarmed seventy-four-year-old man in the name of his ex-girlfriend. Sadly, a viral video was posted to Facebook for two hours before anyone reported it to the police. A more obvious example was the presidential elections when well-intentioned good white conservatives, evangelists and women elected a fascist leader rather than embrace the dis-ease and dis-comfort to resist cheaply selling our democracy for individual interests and temporary market-driven gains. Consequently, “fake news” and “alternative facts” engendered a politics of distraction that locked our attention on the charades of conservatism and not the crisis in Syria, the bombs in North Korea, the extremists in France, the missing girls in Nigeria, espionage with Russia, mysteriously undisclosed tax returns at the White House, allegations of sexual assault by the country’s elected president, immigration in Mexico, mass incarceration in America and violence all over the world. We have been distracted by sensationalism and have become apathetic to the suffering of the Muslim, Mexican, migrant and marginalized. America has increasingly become blatantly desensitized to violence—so much so that we would rather say nothing than to be bothered; we would rather not vote or vote immorally than to vote in the best interest of our democracy, especially if it means electing a democratic-socialist or a woman; we would rather be entertained by viral videos than to participate in eradicating violence. Apathy is an American problem; it is a Christian problem; and it is also a problem of well- (and ill-) intentioned individuals who repeatedly bypass opportunities to resist violence and are indifferent to suffering.

Response

In response to this indifference, I have three suspicions raised by Vasko’s constructive theological and ethical imaginings of white privilege. First, there is the discussion about bystanders as moral agents. Vasko provocatively states “[it is not] my presumption that bystanders are intrinsically bad people. Doing so would imply that bystanders (and perpetrators) are ‘monsters and demons,’ instead of ‘moral agents to be held responsible’ for their action and inaction.’ More importantly, such a perspective renders bystanders incapable of conversion, personal and communal” (10). Bystanders as moral agents? This assertion, in the reader’s opinion, attenuates the effectiveness of the author’s argument. It seems to patronize privilege. While I do not think this is the author’s intention, it reads as hand-holding and apologetic; lukewarm and ambivalent. It seems that the moral compass of a bystander is inherently skewed and this proves their inability to act as moral actors of fairness and justice. Seen this way, White supremacy and the KKK are evil. Homophobia and cis bullies are monsters. Xenophobia and the people who legislate the building of walls are bad people. Law and Order rhetoric that undergirds police militarism and prison construction for the annihilation of poor people is an oppressive structure that has proven incapable of conversion. Bystanders (and perpetrators) cannot be moral agents in the same way that abolitionists are, or in the same way pacifists are, or in the same way justice-seeking activists are. Both, bystanders and the socially awakened, are not two sides of the same coin. They must be different, they must be antithetical, they must be warring or it seemingly compromises the pain and suffering of victims, perpetuates violence and undermines personal and communal accountability. I wonder if in Vasko’s outlining of a bystander culture, whether this is inclusive of only the “well-intentioned, and sometimes, socially aware individuals” or does it make room for the ill-intentioned? When considering white privilege as a result of apathy and complacency, it is hard for me to think critically about the well-intentioned bystanders and not also the monster and demon bystanders—because I believe they do exist, not as moral agents but as immoral predators.

Second, there is the discussion about white guilt. In Vasko’s exploration of sin-talk, she argues that “guilt is not a particularly effective tool for engendering social responsibility” (18). Vasko states, “Often white guilt depends upon the fear or stigmatization of being called a racist instead of the moral impetus to acknowledge harm done, make reparations, and work toward structural change” (107). At its best, “guilt provokes moral scrupulosity, or an obsession with defining ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ behaviors, not mature reflection on social patterns and systems” (107). Vasko’s discussion on guilt is extremely provocative and triggering. If my understanding is in alignment with the author’s argument, it seems that Vasko is underlining the ineffectiveness of white guilt because it immobilizes reconciliatory action. I agree that victim blaming is wrong. However, I would add that shaming the oppressor is sometimes warranted. It seems unfair to soften the blow of accountability with a concern for white guilt in the same way sensitivities are extended to the victims of white privilege. Vasko is right to suggest that Christian theology, such as atonement theory, has perpetuated privileged narratives of structural oppression such as a scapegoat logic to protect white moral innocence (88), but it is tenuous to in the same thought show equal consideration for the culpability of guilt that engenders “white paralysis.” For me, such indictment on vicarious violence as oppressive and the rationalization of white guilt is conflicting. Vasko really drives her point home when she repeats, “Guilt is an ineffective tool for engendering social responsibility” (107). Guilt, she argues, is believed to conjure emotions of shame and blame which “leave people frozen, unsure of what to do” (107). To this end, Vasko argues that guilt is ineffective because it makes white people defensive, it makes them want to protect their ignorance rather than seek a change of action and attitude. This baffled me. When considering the death-dealing circumstances, demeaning and dehumanizing atrocities that oppressed people suffer because of the violence exerted by white normative culture, the oppressed could care less about white guilt. When African-American woman are the fastest growing population in prisons (which is an extension of slavery), who cares about white guilt? When economic wealth disparities and newly proposed tax codes make the rich richer and the poor poorer, who cares about white guilt? When Mike Brown’s televised lifeless and odorous body remained in the middle of a Ferguson street with no cover, coroner or courtesy, who cares about white guilt? Reconciliation should happen whether white people feel good or guilty. This is the essence of accountability. Thus, I am suspicious of Vasko’s construction of sin-talk with regards to white guilt. In fact, I am left with more questions than agreement.

Third, there is the discussion about solidarity in soteriological praxes for privileged people. Vasko describes the silence of solidarity, which is to learn how to pause “to create space for the voices of others and to internalize the meaning of what has been said” (83). Solidarity, understood in the context of the Syro-Phoenician woman necessitates the relinquishing of power and privilege to engage in the work of God’s basiliea and to take accountability of one’s social participation in injustice (183). Moreover, “the goal of human freedom is to be in solidarity (or communion) with God and others” (232). Sacramentally and socially, communion is to be in solidarity with those who suffer and continue to be crucified by structural injustice (216). Solidarity, as Vasko states, is not an “easy road to love and harmony” (201). It is the challenging road of conscientization that enables the oppressor to become aware of their own role in contributing to the suffering of others. It is a positive response to divine grace and the never-ending task of justice. For Vasko, solidarity is all of this, but for me, I think it should be more. Solidarity cannot be a first step to reconciliation. It should be the end goal. While there are mentions of reparation throughout Vasko’s analysis, such as in questioning Jesus’ reparations with the Syro-Phoenician woman, I wonder what does reparations look like for white people in A Theology for Bystanders? Especially as Vasko states, “As members of dominant cultural and social groups, the goal for privileged bystanders is to become allies or advocates in the struggle for justice, in the work of bringing about the kin-dom of God” (12). While this goal is ideal, I am suspicious of alliances without any alms.

In summation, privileged people must learn to live with the dis-comfort and dis-ease of guilt before any reconciliation or solidarity can facilitate healing and justice. This is not a feel-good process. Rather, liberation pulls no punches. In this reader’s opinion, A Theology for Bystanders seems to assuage the messy truth of race relations in America with feel-good concessions that dangles a false net of accountability to make reconciliation more relatable than revolutionary. This brings me full circle to my opening point: A Theology for Bystanders is noble and necessary but not for me, a Black woman. I am not the intended audience of this project and perhaps subsequently I am not the best interlocutor to engage the effectiveness of the proposed process of reconciliation. However, it is for this reason that Vasko’s argument may fold in on itself. This is to say, in the very act of challenging privileged bystanders, the argument itself risks becoming privileged. It seems that Vasko says all the right things; makes all of the right references to liberationist theologians; writes with passion; engages critically with analytical prowess, but something is missing, something falls short, something disconnects an analysis prescribing the privilege of white people from the understanding of the pain of the oppress. This only proves the complexities and challenges of privileged people addressing their own participation in oppression.

In the end, I commend Vasko for the scholarly care in her analysis and for accepting an unpopular charge (there are not a lot of white people talking to white people about white privilege). This is a noble start to a critical task in the project of liberation. My response raises suspicions for consideration from a corollary reader in hopes of connecting the argument holistically and dimensionally so as to not have white people doing the work of reconciliation in a vacuum but to think how it is relatable to the people with whom they seek solidarity. Hence, A Liberation for Bystanders is duly fitting for its target audience and I would enthusiastically share it with the well-intentioned and sometimes socially aware people as a beginning to a larger conversation about race relations in America to move beyond apathy and to prophetic action for social change.

“Trumpism is an amalgamation of racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, islamophobia, militarism, and ableism all strung together for Trump’s self-serving political aspirations. Trumpism is the manifestation of white narcissistic racial political imagination. Trumpism is a knee-jerk reaction or the polar opposite of anti-racist and anti-oppressive liberal social justice education. Trumpism is an inter-sectional racism, that brings together the worst of all society’s ‘isms’ to create an entirely hazardous blend.” Shawn Casselberry’s blog, posted July 21, 2016, https://syndicate.network.shawncasselberry.com/single-post/2016/07/21/Trumpism-A-New-Brand-of-American-Raciam (accessed April 30, 2017).↩

I recommend attention to chapter 10, “Liberation and Reconciliation,” in God of the Oppressed (Cone, 1997).↩

10.23.17 |

Toward a “Radical Reordering of Esteemed Values”

You have known violence. You have known violence. You are queer and you are brown and you have known violence. You have known a masculinity, a machismo, stupid with its own fragility. You learned basic queer safety, you have learned to scan, casually, quickly, before any public display of affection. Outside, the world can be murderous to you and your kind. Lord knows.

But inside . . .

—Justin Torres, “In Praise of Latin Night at the Queer Club”

As I read Elisabeth Vasko’s Beyond Apathy and contemplated what is at stake in getting decent White Christians up out of the pews, I was reminded of Justin Torres’s poetic and indicting commentary on the Pulse Nightclub shooting. In the early hours of June 12, 2016, a gunman opened fire in Pulse Nightclub, an LGBTQ+ venue in Orlando, Florida, killing forty-nine people and injuring fifty-three. It was Latin Night at Pulse, and the majority of the victims were members of the Latinx community. Torres’s first response, published by the Washington Post on June 13, 2016, offers an intimate portrait of the varying shades of politicized and personal vulnerability that color Latinx queer experience in America. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, Torres’s portrait countered a variety of other first responses from public officials, the media, and religious leaders who intentionally or unconsciously used this mass execution as a surrogate for a number of tangential agendas—White Christian awakening, shows of mercy, anti-Islamic nationalism or on the flip side, reminders of Muslim vulnerability, even “safe space” advocacy. Torres, rather, reflects on the scene inside the hearts of the club-goers: “You didn’t come here to be a martyr, you came to live, papi. To live, mamacita. To live, hijos. To live, mariposas.”

Torres’s move to counter a narrative of queer martyrdom and locate subjectivity in a mixed brown crowd dancing in the disco light brings into stark relief some of the key elements of Vasko’s agenda. First is Vasko’s disavowal of redemptive suffering and the connections she makes between overt acts of abuse and violence like what happened at Pulse and the everyday violence perpetrated against vulnerable communities in our society through condemnation, mixed messages, and/or indifference. Vasko evokes Dorothee Söelle to explain apathy as the chronic condition of the systemically privileged. Apathy or apatheia in the Greek refers to an incapacity for suffering, or as Söelle describes it, “the person and his circumstance are accepted as natural, which even on the technological level signifies nothing but blind worship of the status quo: no disruptions, no involvement, no sweat” (Vasko, 70–71). Vasko shows how Christian lust for dead bodies, moral scapegoating, and a lack of personal experience with suffering allows the privileged to justify passive bystander responses to racism, LGBTQ+ bullying, and slut shaming. All of these tendencies are evident, for example, in the local and national Roman Catholic leadership’s response to Pulse. However, as I propose later in this essay, curing apathy is insufficient to bring about a livable world for those living irregular lives. This will require active dissent and not just a reordering of those most “esteemed values

Bishop John Noonan presided over what was characterized as an interfaith vigil for the victims of Pulse at St. James Cathedral in downtown Orlando on June 13, 2016. As reported by Christine Young and Teresa Peterson of the Catholic News Service (CNS), the official news agency of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, Noonan was joined by another Florida bishop, Roman Catholic priests from across the diocese, leaders of several other Christian denominations in Orlando, and Imam Tariq Rashid of the Islamic Center of Orlando, all male clerics (June 15, 2016). According to Young and Peterson, Noonan’s message emphasized monotheistic unity, the dignity of human life, and mercy for the victims of Pulse and their families. Noonan recalled his experience with violence in his home country of Ireland and so by analogy assigned a nationalistic-religious conflict to the Pulse shooting. Young and Peterson also spotlighted the homiletic remarks of Bishop Curtis Guillory at a similar vigil in the Diocese of Beaumont, Texas. Guillory warned congregants against blaming the entire Muslim community for the act of an individual Muslim, saying, “We did not blame all of the Germans for Hitler nor did we blame all Anglos for what happened in Charleston,” referring to the deaths of nine church-goers after a gunman opened fire in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015.

The institutional blindness and avoidance of accountability evident in the Catholic leadership’s response to Pulse is staggering. Consider the false analogy between Muslim religious identification and the ethnic identifications of German and Anglo in Guillory’s remarks, an anti-Semitic sidestepping of Christian culpability in the Holocaust and in the persistence of racism in America. More pertinent to Pulse is the complete avoidance of the reasons that Latin Night at the queer club was targeted. Fundamentally, this was an act of homophobic, xenophobic violence. As Torres’s reflection in the epigraph above reveals, at the core of this kind of violence is a fragile masculinity, a disease that cannot permit nonconformity or tolerate its own social or sexual vulnerability, a pathology shared by clerics, governors, and gunmen alike. Heteropatriarchal religions transmit especially pernicious strands of this infection as they conflate cultural values with divine order. As one of the student activists in my 2010 ethnographic research pointed out, “you take religion out of the equation, there’s no justification for what anyone does you know, against the LGBTQ community.” Of note is that many Christian denominations and communities have had a change of heart when it comes to LGBTQ+ inclusion. Other interreligious vigils in Orlando following Pulse were much more affirming and reflexive of LGBTQ+ and Latinx vulnerability. However, the majority of Christian denominations and other religious traditions in the United States and globally maintain ambivalent or condemnatory stances on LGBTQ+ inclusion.

Once this diagnosis is accepted, such communities must face squarely the entanglement between upholding social sexual norms and violent extremism. When the church is unable to acknowledge its ongoing complicity in the public and clandestine executions of queer people across histories and geographies, vigils become opportunistic shows of Christian values, such as mercy and dignity, gross usages of such executions to further the narrative of redemption without the costliness of repentance and repair. Catholic and other religious officials’ focus on “conversion of heart for all who perpetrate acts of terror in our world” echoes the homonationalist response of state officials and obstinately denies the moralistic terrorism that religious and political institutions have perpetrated against queer persons and communities for millennia (Noonan, June 13, 2016). Liturgies become narcissistic morality plays, and borrowing Vasko’s words, reveal that like Jesus’ body, in the Catholic moral frame, queer bodies are only redeeming when they are dead and so give the community and the leadership an opportunity to exercise mercy (73). Also absent from these political and liturgical worldviews is special care for the courage and vulnerability of Latinx subjects negotiating norms of inclusion and exclusion—documented or undocumented, Spanish or English-language liturgies—struggles that as Torres points out are suspended inside Latin Night at the queer club where “the only imperative is to love.”

Incidentally, Guillory’s reliance on “Anglo” decency to dissuade congregants from anti-Muslim anger in his analogy between the shootings at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston and Pulse Night Club affirms Torres and others’ sanctification of Latin Night at the queer club. Xiomara Verenice Cervantes-Gómez, for example, in her June 13, 2016 essay for Religion Dispatches, writes, “When thinking about the theological significance of these spaces for queer people, to not talk about racial experience is to fold black and brown bodies into a history we have consistently been excluded from. And more than that, these are our ceremonial centers. These are our places of worship.”

All theologians use surrogates. Jesus did, or at least those evangelists who dug up and arranged the stories about his life. Similar to physical forms of surrogacy, gender subordinates, especially women from “unclean” ethnic groups and/or indecent backgrounds are the ones most frequently and violently conscripted into rhetorical deputation for the sake of revelation (130). The Bible is one of the most fecund and treasured sites for unearthing these varieties of usage, many corresponding directly to the genres of actual sacrificial violence perpetrated against gender and sexual subordinates—taking the fall, enslaved conjugal surrogacy, daughter sacrifice, gang rape, dismemberment, fostering God’s offspring, dishing out foot rubs, facing a stoning for sexual improprieties (partner in absentia), and being branded “the great harlot,” dwelling place of demons and kick-starter of the apocalypse. Perhaps catechists and preachers should start with a trigger warning. Gender critical interpreters have lamented the display of women as pedagogical objects in the biblical tableaux, often arranged so as to teach the reader something about appropriate response to the divine or what may happen if you stray from the norm. As Phyllis Trible observes in Texts of Terror (1984), these stories should haunt us because they signify the remains of women scattered and buried across the world. Womanist theologian Delores Williams in Sisters in the Wilderness (1993) is one of the first to excavate both race and surrogacy in these accounts, reading the story of Hagar as analogous to Black womens’ experience of conjugal, maternal and labor surrogacy in America before and after slavery. Despite the biblical authors’ pedagogical aims, the complexities of these women’s worlds fill the margins of the text as they trigger their readers’ incarnate subjectivities, or not in the case of those blinded by apatheia.

Vasko turns to the intervention of the Syro-Phoenician woman in Mark’s gospel to articulate how structural sin (i.e., racism, xenophobia, heteropatriarchy, etc.) inhabits and habituates the body of Christ, both the New Testament Christ and the still evangelizing ecclesia that legitimates its identity and norms by recourse to his. In this story, Jesus first ignores a woman asking for his help and then calls her a dog because she is not Jewish. As Vasko points out, in the Bible, “dogs are likened to male prostitutes, evildoers, and headstrong wives, and they are grouped with sorcerers, fornicators, murderers, and idolaters” (179). Therefore, Vasko argues, “Jesus’ response . . . not only bears the marks of ethnic prejudice and religious exclusivism but also patriarchy. As a barking dog must be restrained by a chain, this ‘shouting,’ ‘begging,’ and unclean woman needs to be restrained lest she wreak havoc on the rest of society” (179).

The evangelical conflation of race-gender-class-sexuality, as well as Jesus’ demeaning social outlook is further exhumed when considering comparable archetypal narratives from the other gospels. Take for example in John’s gospel the disciples’ astonishment when they find Jesus talking to a woman in public, and a Samaritan woman to boot. (Similar to the Phoenicians, the Jews in first-century Palestine had an antagonistic relationship with their Samaritan neighbors.) Jesus meets his Samaritan lass at a well, recalling other folktale flirtations from the Jewish canon. However, what begins with a pick-up line—“Give me a drink”—quickly progresses to a disclosure of the woman’s sexual history—“You are right in saying, ‘I do not have a husband.’ For you have had five husbands, and the one you have now is not your husband.” Here and in the encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman, as Vasko implies, Jesus is a perpetrator of slut shaming. This is a form of legit violence as the norms Jesus uses to demean these women are validated by his divinity. For the gospel writers, these narratives function to legitimate ministry for those outside of the Jewish community (mercy), while also proscribing gender, sexual, and social norms (chastity).

Slut-shaming is one of the forms of social violence that Vasko highlights in her larger project. Although she does reflect on the ways that gender, race and class often inscribe this kind of bullying, she stops short of offering a critique of the sexual norms professed by the label “slut.” Vasko falls into the trap of defending victims based on their innocence. She does not take the opportunity to fully dismantle Christian sexual values such as abstinence and monogamy. What about those who are living irregular lives, to use the language of Catholic ecclesial authorities? This is where I think dance lessons from sex-positive queer scholars is vitally necessary—so long as the ecclesia holds on to its esteemed values—those rules of exclusion and inclusion, belonging and non-belonging, redemption and damnation—it legitimates violence to defend those norms.

Vasko’s limited vision is related to whom she is writing for. Vasko deputizes feminist, Black theological, and postcolonial interpretations of this story to argue for the dislocation of divine utterance outside the Body of Christ with the goal of bringing those voices into the fold, the same goal, ultimately, as the evangelists. Vasko’s goal in this book is to mobilize decent White Christians via compassion to new shapes of relationship and intimacy with those on the margins, i.e., “solidarity,” a slippery concept for decent White theologians mainly because solidarity is not conceptual. Solidarity is experienced. M. Shawn Copeland mentions solidarity in her lecture “Discipleship in a Time of Impasse” (Loyola Marymount University, April 16, 2016). Copeland speaks of the solidarities that are possible in coalitions between suffering communities fashioned through mutual identification and the realization of interdependency in struggle. For example, a girl with a reputation and a Latinx gay coed can relate because they both know what it’s like to vanquish haters. They know how to learn through experience and forge principles that make sense in irregular circumstances. They understand the kind of creativity and audacity that are necessary to survive the violence of everyday life. Solidarity, then, is not a virtue of the privileged. It is a necessity of the marginalized.

George Yancy

A Theology of No Edges

Beyond White Christian Neoliberalism

Elisabeth T. Vasko’s book, Beyond Apathy: A Theology for Bystanders, powerfully brought to the fore not only a network of philosophical ideas of which I am currently engaged, but her book touched, affectively, aspects of how I understand my theological, ethical, and political being-in-the-world. More accurately, Vasko’s work confirmed my commitment to the inextricable link between the conceptual and the affective, their complex interplay and the rich forms of discernment that can result.

At seventeen years old, I knew I wanted to study philosophy. Wonder was my constant companion: What is the nature of ultimate reality? What is the meaning of death? Does God exist? Which religion possesses the “indubitable” narrative about the origins of humanity, the creation of the cosmos, and the nature of God? In fact, I fell in love with Plato’s metaphysics. Obsessed with the idea that there are immutable Platonic Forms, I desired to discard the world of appearance, which, for Plato, is tied to opinion, and to dwell among the Forms, to gaze upon those eternal objects that are beyond space and time, a realm that guaranteed absolute knowledge. In addition to being raised a Christian, it was Plato’s metaphysics that sustained my preoccupation with all things otherworldly, especially God. For me, the telos of philosophy was wonder and it promised something metaphysically ethereal.

As I began to define more effectively my vocation (etymologically, to call) in philosophy, I found that there was a meta-philosophical shift in my thinking about philosophy. There was also a shift in my thinking about and my affect toward the everyday, the mundane, the quotidian. The suffering of human beings through painful and unjust processes of racism, whiteness, sexism, classism, and oppression, came to govern the philosophical space that I inhabited and within which I now reside. Unlike the intellectual, contemplative realm of Platonic Forms, the subject matter that accompanied my meta-philosophical turn was and is a painful philosophical space of engagement. It is a space of lynched Black bodies. Broken necks and flayed Black bodies. Castrated and raped Black bodies. Unarmed killings of Black bodies by the white state and proxies of the state. The pervasiveness of stark poverty in a world of capitalist greed and wealth. The homeless who we see as untouchable and malodorous. The objectification of women’s bodies. The rape of women and their domestic brutalization. The sexual oppression and violence suffered by children. Sex trafficking and the violation of innocence. Cruel death and dying all around us/me. The stench of rotting corpses caused by acts of injustice that we attempt to sanitize through profound acts of rationalization and bad faith. The suffering of refugees and the ostracizing of our neighbors. After all, we often render those who are invisible to us, who die around us, as “not quite human” or simply “sub-persons.” And then there is the killing of the earth and our uncaring elimination of its beauty and our hegemonic domination of its gift-giving capacity. That and so much more is the living hell that we live with. In the face of that, how can philosophy, my practice of philosophy, remain apathetic (etymologically, without pathos or suffering)? Abraham Joshua Heschel writes, “If all agony were kept alive in memory, if all turmoil were told, who could endure tranquility.”

It is not that philosophy has ceased to function for me as a site of wonder; rather, inextricably linked to that wonder is now suffering. Hence, for me, to do philosophy is to suffer. One might say that I combined Plato’s vision of Socrates as the quintessential philosopher of reason with the vulnerability of Saint Augustine of Hippo. The latter was a philosopher who wept, unafraid to be vulnerable and to reveal the aguish associated with that vulnerability. The value of philosophy, and the existential gravitas that this involved, was back in the cave, the space of fragility, mutability, appearance, and ignorance. It is within the cave of deep existential sorrow and uncertainly that I now tarry; a space of finitude, one that places all of us on the precipice of imminent death.

In the middle of lecturing in my philosophy courses, I will often stop and ask my white students, especially as I teach at a predominantly white institution (PWI), to envision a Black female prostitute, sometimes just a few blocks away from the university, who undergoes degradational acts of perverse sexual objectification and endures sexual violence because she is addicted to crack cocaine or heroin. I point out that there are whites (many, by the way) who don’t seem to give a damn about her violation partly because she is Black. They fail or refuse to see her as a victim, but as somehow responsible for her own circumstances. And while this white distortion is predicated upon an epistemology of ignorance, and white privileged indifference, I also point out to them that many of us, regardless of race, refuse to see her. Heschel writes, “The prophet’s word is a scream in the night.”

As a philosopher who engages philosophy as a site of suffering, deep responsibility, fearless speech and fearless listening in the face of so much violence and terror, and as a philosopher who is a Christian hopeful theist, meaning one who hopes with love that the divine exists, even as there is no absolute epistemological guarantee, I was profoundly moved by Vasko’s important text. I agree. Too much is at stake. Hers is a text that invites dialogue, the kind of engaged dialogue that refuses to hide from what is truly at stake. She writes, “In contexts marked by violence, hiding can be risky business, encouraging passivity and escapism, and sapping the world of the vital and creative energy needed for transformation” (33). For Christians, Vasko has written a dangerous text; dangerous because it complicates Christian identity and forces us to embrace our complex historicity and institutional facticity.

Vasko challenges a deeply problematic conceptualization of human beings as neoliberal, atomic subjects. She writes, “To be human is to be a person in relation” (220). Her rich theological anthropology provides an important foundation for theologically recasting such themes as innocence, apathy, bystanders, sin-talk, complicity, and responsibility. Through a complementary conceptual frame, Vasko’s view raises what I have only recently begun to theorize as the rethinking of a radical relational ontology: a body with no edges. An ontology and ethics of no edges, as I’m using the term here, involves rethinking the body as not terminating at a corporeal edge (or outside limit). This forces the rethinking of the meaning of distance. Our bodies are always already haptic, touching. So, for example, my students’ whiteness, their white embodiment, is always already haptic vis-à-vis Black bodies and bodies of color within a context where whiteness / white racism is systemic, constitutes the transcendental norm, and where there is no escape because of a fundamental mutual corporeal embeddedness within a racialized Manichean divide. There is no edge to their white bodies. Contiguous (“touching upon”) within a racialized and racist social integument or skin, my white students’ embodied modes of being actually belie separateness. Distance, which implies “standing apart,” then, needs to be rethought within the context of political hegemonic processes that are systemic and that involve processes of interpellation or hailing. Regarding whiteness, when the past continues to exist in the present through the materialization of white habitual modes of existence, white institutional practices, white social locations of power and privilege, white gazes, white violent discourses, and white silences, Black bodies and bodies of color suffer in their embodiment. The objective is to get my students to think about the ways in which their white privilege and power are contingent upon and contiguous with the oppression of Black bodies and bodies of color. While counterintuitive, I encourage my white students to begin to think about their bodies as having no edges; hence, their embodiment can be said to extend across space and time. In the classroom example given above, as a male professor, one who is complicit with sexism, I am impacting, which is a species of touching, the Black female prostitute. As Vasko suggests, my innocence is also a myth. She writes, “The nature of one’s responsibility and complicity is contingent upon one’s social location” (138). Hence, whether “passive” or active with respect to the perpetuation of sexist oppression, as a male who benefits from sexism, I am still responsible. In short, it is easy for me to say, “But, wait, I’m not ‘out there’ abusing her. I have not and will not offer her any money. In fact, I’m the sophisticated male ‘feminist’ who knows better.”

Two points. First, this declaration can function as a form of what Vasko terms hiding, where I lay claim to a form of embodied and ethical autonomy that “frees” me from violence vis-à-vis the Black woman. On this score, “hiding can be risky business, encouraging passivity and escapism, and sapping the world of the vital and creative energy needed for transformation” (33). I attempt to hide/escape from myself and the ways in which I am constituted in complex ways as sexist. Hiding, for Vasko, rightly risks solidarity. Heschel writes, “But faith only comes when we stand face to face [and] suffer ourselves to be seen.”

Like white racism vis-à-vis white embodiment, sexism is etched into my soul and involves multiple layers of complexity. In fact, I am often ambushed, a term of mine that Vasko deploys with deep theological insight. She writes, “Ambush can be seen as a form of redeeming grace, opening pathways for privileged persons to enter into solidarity with the oppressed” (216). While Vasko uses “opening pathways,” I have come to use the metaphor of un-suturing as it implies forms of embodied opening, a rupture that transcends epistemic accommodation.