Saving Karl Barth

By

12.15.14 |

Symposium Introduction

12.17.14 |

Response

To Trust the Person Who Wrote the Books

The thesis of this book is that von Balthasar spotted that when Karl Barth criticized the Catholic idea of an analogy of being between creatures and God, he had confused the Catholic analogia entis with the doctrine of a “pure nature,” used by Tridentine Catholic theologians to theorize a virtual reality which is emptied of grace. Long’s thesis is that von Balthasar thought that when Karl Barth heard “analogy of being between creatures and God” the word “creatures” got itself translated into “pure nature” and so Barth imagined that Catholics were constructing a real (rather than hypothetical) foundation for theology upon this “pure nature,” which is graceless and Godless. Long observes that von Balthasar has not only this negative observation about Barth to contribute, but also a positive perception of a “turn” toward acknowledgement of the “analogy” made by Barth round about the time he wrote his book on Anselm, and which is apparent in the Church Dogmatics. Barth may prefer to call it “analogy of faith” rather than “analogy of being,” but in effect he has perceived that, in the person of Christ, there is an analogy between creature (created human nature) and God (uncreated divine nature), and that this analogy is the operative center of theology. Long’s thesis is, moreover, that von Balthasar was right about this, and not merely right about that as a textual claim with regard to Barth’s writings, but right about reality—there is a Christ-formed analogy of being between creatures and God, and above all there is no non-hypothetically, actually existent pure nature.

As Long notes, von Balthasar appeared on the Basel scene quite early, towing a volume of the Dogmatics around in his briefcase “like a puppy” (Barth’s words). Maybe, and Long encourages the supposition, there was something Heisenbergian going on here, not in the Walter White sense of the production of crystal meth in the back of an old Volkswagen, but in the sense of the observer affecting the data, and the Swiss Jesuit’s perception of the Reformed pastor influencing Barth’s own theological trajectory. (You cannot be too careful around members of the Society of Jesus). Saving Karl Barth uses history and biography as its material for theology. He shows how, for instance, von Balthasar’s presence at Barth’s seminar on the Council of Trent, and its influence on his conception of Baptism, in its turn affected Barth’s later ideas about the “sacrament of faith.” The book is full of interesting details about the decades-long conversation between Barth and von Balthasar. The simpler version of the thesis of the book is that this conversation was valuable because it encouraged Barth to move toward analogy and encouraged von Balthasar to allow Christ to condition every facet of his theology. The affective heart of the book is the defense of the proposition that Protestant and Catholic theologies bear most fruit in dialogue with one another. The issue within which this desire for ecumenical dialogue is elaborated is that of pure nature versus “always already graced by Christ nature.”

Long defends this thesis against two kinds of critics. On the one hand, there are Protestant theologians who think that von Balthasar’s interpretation of Barth is flawed. Barth never, according to Bruce McCormack, simply turned from being a dialectical theologian who denied analogy between God and creatures, to being a theologian of analogy. McCormack claimed in his biography of the Swiss theologian that Barth continuously maintains a dialectic of “veiling and unveiling,” throughout the Church Dogmatics. On this historical reading of Barth’s development, he makes no decisive turn from dialectical theology to a theology that assumes analogy between God and creatures. Plus, as McCormack has it, von Balthasar fails to note the real decisive new step that Barth takes in Church Dogmatics II.ii, when he puts the “election” of Christ at the center of his theology. McCormack first set forth this claim in volume one of his Barth biography. Instead of writing volumes two or three , he went on to write systematic, theological works in which he drew out the implications of this “Barthian evaluation” of election. The theological proposal which McCormack’s reading of Barth on election elicits is that God’s eternal act of electing humanity in Christ entails that God has eternally bound himself to humanity in Christ—and thus that God’s act of “electing” the Word bound God to become Incarnate. Or, again, to put that in crude terms, one kind of critic of his thesis is “too Protestant” to accept von Balthasar’s salvaging of Barth’s tendency toward a Christological analogy of being. Instead of Christic analogy and Incarnation, McCormack presents election, event, and opposition to traditional metaphysics as the central lesson to be learned from Barth’s theology. Especially in its apparent eschewal of metaphysics, that pushes Barth (and Protestant theology) too far into, as it were, a Protestant extreme, for Catholics to have anything much to say to Protestants.

On the other hand, there are those whom Long calls Ressourcement Thomists, who criticize von Balthasar for his lack of metaphysics. These in effect defend the idea of pure nature, claiming that theology is impossible without a foundation in “nature,” in a pre-theological or non-theological sense of the term “nature.” Those who promote this criticism of von Balthasar are Catholics, and were their opinion to prevail it would push Catholic theology too far into, as it were, hard Catholicism, for Protestants to have much of anything to say to Catholics. We learn about two Catholic critics of von Balthasar’s treatment of nature, pure and applied (graced). One is clearly Saving Karl Barth’s good cop; the Dominican Thomas Joseph White is presented throughout as a thoughtful and open-minded theological critic of von Balthasar’s failure to give “nature” its due. Whatever he thinks about the principle of non-contradiction, it must be annoying for a theologian to coexist at one and the same time, if in different places, with another thinker who has with diametrically opposed opinions and yet nearly the same name as himself. Steven A. Long takes the role, in this book, of the bad cop, indeed, one has to say the poor theologian, who confuses the councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon and defends the real existence of pure nature on purely political grounds. As quoted in Saving Karl Barth, Long explicitly defends the necessity of a doctrine of pure nature on the grounds that, without it, it is impossible to argue for public prayer in schools, or for any other accoutrements of Christian influence on the secular State. Another figure who creeps from time to time into this narrative is the old, anti-Ressourcement Thomist, Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange. Saving Karl Barth is too polite to mention Garrigou’s own political engagements, as expressed for example in his use of Vichy Radio to promote French anti-Semitism in 1941 or his production of an introduction to an edition of Thomas Aquinas’ De Regimen Principe just a few months before the condemnation of the Action Francaise in 1926. The proximity of “pure naturism” to monarchism and Gallicanism (or in our own context, Americanism) still calls for further exploration. Even without mentioning these embarrassing episodes, Saving Karl Barth gives us a whiff of what Garrigou’s theology smells like, in a state of nature. Garrigou and his kind were influenced by similar political concerns to those that, according to this book, motivate Long. But not White: Long treats White’s defense of a philosophy of nature with respect. It is very tempting for those who don’t think an actual (as opposed to hypothetical) state of pure nature exists to regard their opponents through reductionist filters, and to say, for instance, “it’s all about reducing theology to politics.” Long’s polite and conversational mode with respect to Thomas Joseph White shows that this temptation can and must be withstood.

What I like most about this book is the way it shows that both the post-Metaphysical, “extreme Protestant” and Ressourcement Thomist, hard-Catholic, depersonalize theology. Theologians are persons, and books express their author’s personality. And yet, by ignoring statements which Barth made about his own development—such as that von Balthasar was right about locating his theological maturation in the Anselm book, or what Barth himself said about analogy and its place in theology, and what he did not say about election, and how it could be a principle which actively defines who God is—McCormack bypasses the person of the author, wresting his texts away from their source of life and creator. Does the person of the author have a deciding say in the meaning of his writings? Long repeatedly “trounces” McCormack on points of logic, leaving me wondering if, however illogical McCormack’s position, it might not be Barth’s own. But within a page or so Long will back that up by showing how the “extreme Protestant” reading of Barth, which so centralizes the “election” of humanity in Christ as to give Christ an eternal human nature bound for Incarnation, is at odds with Barth’s own texts. Likewise, the hard Catholic who wants to replace what he or she sees as an excess emphasis on grace with a “re-sourcement of nature,” is interested in a metaphysics of nature, not of persons. Persons are not the most fundamental and “hardest” feature in the metaphysical landscape of “hard Catholicism.” That seems to indicate that the Incarnation of divine and human nature in the single person of Christ, and the three divine persons of the Trinity are not the deepest inspiration of the Catholic “return to metaphysics.”

So what I thought was best in this book, with its rather devastating critiques of Steve A. Long and Bruce McCormack, was its defense of “personalism.” The author might fault me for this, and want to say it is the person of Christ who is at the center: it is the person of Christ who makes the marriage of the two, divine and human, natures possible, not the existence of “natures” in a raw, ungraced state (A. Long), or even that of persons. I would say that that theological point is absolutely true, and this is what has, over the centuries, made the person the subject of ever-deeper philosophical and metaphysical investigation. To me, where both of the author’s “extremes” meet is not so much in lack of enthusiasm for ecumenism as in antipersonalism. But, of course, I too have a personal stake in this: Bruce McCormack’s biography was a huge inspiration to me when it first appeared, because it made me realize that biography and history can be the material of theology. It made me write a (much less good) biography, and the writing of which cured me forever of formalism; writing it made me realize that in order to understand a writer’s books one must trust the writer himself, the person who wrote the books. Biography is not a matter of romantic identification with the author, but of trusting him or her as one trusts another person. This became my own hermeneutic, and it is clearly the hermeneutic that guides Saving Karl Barth. Without such a “personalist” hermeneutic, one can cite Barth against McCormack until one is blue in the face, and the reply will be, simply, that the author is not the best judge of his own work, does not know, for instance, whether or not he turned to analogy in 1932. Long will still have in hand logical criticisms of McCormack’s position, and very powerful ones too, but this will be the only evidence he can call in, without the assumption that a personalist hermeneutic is the one which makes best sense of an author’s work. The three of us (Murphy, Long, and McCormack) have written theological books whose material is history and biography: is there anything to learn here about theological method? Long clearly thinks so. He notes the significance of the St. John communities, set up by von Balthasar and Adrienne von Speyr, which still exist, as a flesh-and-blood, existential “hermeneutic” of von Balthasar’s writings, and observes that Barth’s writings, by contrast, have been propounded by a Protestant “elite.”

For me, Saving Karl Barth was a very exciting book. Von Balthasar’s book about Barth was composed at exactly the time when Henri de Lubac’s criticisms of the doctrine of pure, ungraced, nature were becoming known, and, in their turn, criticized by important figures in the Roman Curia such as Réginald Garrigou-Lagrange. It was published just a year or so after de Lubac was silenced by the Jesuits (not by Rome; no Dominicans were involved in his silencing). I’ve always thought that von Balthasar’s book about Barth was in some way a contribution to this debate but I’ve never been able to put my finger on how. Saving Karl Barth explains how, repeating the mantra about Barth’s mistranslating analogia entis into “pure nature” umpteen times until it had first got itself into my thick skull and then went round and round inside it like a pop song which gets stuck on a repeat loop in one’s memory. The book could easily have shed fifty pages and been quite perfect. The reiterations certainly help to hammer home a difficult thesis in the early stages of the book, but eventually they become wearisome. People will skim through parts of the book and that’s a shame because it has a gem at its heart.

The only objection I can find to the content of the book is that the author says that von Balthasar disagreed with Vatican II. He is making a strategic gesture here: he wants to say that post-Vatican II liberal Catholicism played to Barth’s fears, by seeming to resort to yet another worldly foundation, of welfare and philanthropy. All of it was done in a “nice” way, not the hard way of the Thomists, but it nonetheless permitted a “pure,” graceless and Christless nature to condition Catholic theology. In her book on Culture and the Thomist Tradition, Tracey Rowland ascribed such a view of Vatican II to Ratzinger and von Balthasar. But, as Larry Chapp pointed out at the time, in Nova et Vetera (Winter, 2005), von Balthasar never criticized the texts of Vatican II: he thought the problems of the post-Vatican II Church were due to the worldliness of our Bishops, not the Conciliar texts. Long’s book has a really good grasp on the texts of von Balthasar and Barth, and this is the only time, so far as I can see, that he slips up on either of them. He doesn’t give any textual support for the broad claim that von Balthasar objected to Vatican II. There may be one or two places where he criticizes spots in certain texts (he thought Lumen Gentium underplayed Mary’s personality), but, as Long shows here, von Balthasar thought Trent does not have the last word in everything: no responsible author would say that von Balthasar “disagreed with Trent.”

But these are very minor criticisms. This is a tremendous book that will have a role in future Catholic and Protestant conversations about Thomas Aquinas, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and the future of speculative theology.

Response

Reclaiming the Christological Center: D. Stephen Long on Christ, Ecumenism, and Theological Friendship

Some years ago I began to observe an interesting phenomenon at meetings of the Karl Barth Society of North America, usually held in conjunction with the AAR/SBL annual meeting. Increasingly these events were populated by younger evangelicals, some studying at traditional evangelical bastions like Wheaton and Baylor, others at Duke or Yale or Marquette. Moreover, these young scholars often seemed as conversant with Barth’s friend and conversation partner, Hans Urs von Balthasar, as with Barth himself. I recall well the occasion when a Barth society panel featured a much-heralded book by a conservative Roman Catholic who was highly critical of Balthasar. I was bemused to observe the evangelicals rushing to the defense of the great Catholic kenoticist. I recall thinking to myself, “these are interesting theological times.”

That evangelicals should find Barth’s theology so attractive might have been a surprise to Carl Henry or John Stott, although perhaps less so in Stott’s case; it was in America that Barth was often seen as dangerously “liberal.” That they should find Balthasar attractive would likely have been shocking. Yet in hindsight, we can see why this might have been so. Barth’s theology offers a powerful array of resources not only for evangelicals, but also for Protestants more generally, to confess Jesus Christ with boldness while avoiding a reactionary stance toward modernity. Barth allows one to be “orthodox and modern,” as Bruce McCormack put it. What Balthasar represents, even more so than Barth, is an opening toward the ancient church, the Fathers and yes, even the medieval scholastics, that seems increasingly compelling in face of a Protestant church life that seems ahistorical and lacking in ontic depth. When I was in graduate school in the 1980s, the reading of Aquinas by Protestants still seemed edgy and avant-garde; today nobody thinks twice about it. Astonishing commonplaces like these should be taken into account whenever people talk of an “ecumenical winter.”

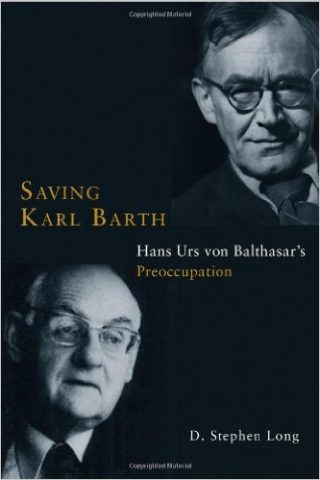

We should not assume that developments like the ones I have been describing are inevitable, the result simply of sociological forces or of some murky Hegelian convergence. Individual historical agents matter. At least part of the credit for the renewed possibility of Catholic-evangelical encounter can be traced to the two men I have already been discussing. In the early 1940s Karl Barth and Hans Urs von Balthasar struck up a strange friendship in Basel, and the theological world has never quite been the same. D. Stephen Long’s Saving Karl Barth: Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Preoccupation is devoted to that friendship and its long-term significance for the churches today. It is a carefully argued book, but also a passionate one. As Balthasar wrote about Barth, “He is passionately enthusiastic about the subject matter of theology, but he is impartial in the way he approaches so volatile a subject. Impartiality means being plunged into the object, the very definition of objectivity” (89). Much the same could be said about Long’s writing.

In the opening chapter of the work, Long does a wonderful job of describing the complexities of Barth’s and Balthasar’s friendship. If overly detailed at times, the material will nevertheless be useful to future scholars. One of the things we learn is the price Balthasar paid for his “preoccupation” with Barth. In the 1940s he experienced constant difficulties with his ecclesiastical superiors, delaying the appearance of The Theology of Karl Barth by a decade. Balthasar’s loyalty to Barth is all the more admirable given the latter’s habit of making harsh pronouncements about Catholicism. As late as 1954 he said to a Protestant audience that no “decent person” could become a Roman Catholic. In the 1960s his mind changed again, as he approved the Catholic ressourcement associated with Balthasar, de Lubac, and a whole generation of younger Catholics. In 1966 he travelled to Rome to confer with many of the fathers of the Second Vatican Council. His critically sympathetic reading of major conciliar documents is to be found in Ad Limina Apostolorum, a work that deserves to be better known, in which he expressed the worry that Catholics might simply be treading the accomodationist path of modernist Protestantism. It was a worry that Balthasar would come to share.

This is, make no mistake, a book of advocacy. Despite the ecumenical advances I spoke of earlier, Long is worried that we are entering a new period of confessional retrenchment or even identity politics in the churches. A generation of younger Catholics seeks to retrieve the thought of nineteenth century Neo-Scholasticism, shocking their elders, who had thought they had said good-bye to all that at Vatican II. Meanwhile an influential school of Barth-interpretation is seeking to overthrow the idea that Barth made a “break with liberalism” or that he ever moved “from dialectic to theology.” Barth was a consistently dialectical thinker, according to McCormack and his allies. Just so he was theologically a modern—a critical modern, yes, but then criticism is what modernity is about. In this respect Barth has far more in common with Schleiermacher than with Aquinas, or at least with Aquinas as interpreted in a certain way. The important thing on this reading of Barth is that he tried to do serious Christian theology “under the conditions of modernity.” Those conditions are post-metaphysical, as the radical Barthians never cease to remind us. Their diagnosis agrees perfectly with that of the neo-neo-Thomists, except that the latter view modernity’s loss of metaphysics as nothing less than a disaster.

The situation just outlined sets out the agenda for Long’s project: recovering what Barth and Balthasar thought they had discovered, what drew them together despite all their differences (never fully resolved) over particular theological issues. What drew them together was Jesus Christ. More precisely, the terrain Long seeks to recover in this book is that of a comprehensive Christocentric view of reality, encompassing the divine and the human, nature and grace, doctrine and ethics. Though in very different forms, such a vision is embodied both in Barth’s Church Dogmatics and in Balthasar’s The Glory of the Lord. Long is frankly puzzled that anyone would want to reject this vision, either by returning to a static theology built on “pure nature” (the Thomist option) or by rejecting metaphysics altogether in favor of a kind of historicism (the radical Barthians). Long’s project, in brief, is to find a via media between these extremes.

Or should we say a via dialectica? An interesting feature of Long’s method is that he essentially adapts Barth’s procedure in Church Dogmatics 1.1 of navigating between competing “heresies.” In that volume, the heresies in question are identified as Roman Catholicism and liberal Protestantism. Both silence the Word in favor of human certainties, whether the ecclesial magisterium or modernity’s rational/experiential subject. Long keeps the method but changes the players. He replaces Catholicism with neo-Thomism and liberal Protestantism with radical Barthianism. The desired space in between is Barth as Balthasar would like to have read him—a theologian in the Reformation tradition, to be sure, yet one whose evangelicalism affirms Catholicism’s fundamental commitment to the created order. To be sure, nature is to be understood only retrospectively, in light of the economy of salvation. Here Long decisively parts company with the contemporary neo-scholastics. On Long’s reading, Barth’s polemic against the analogy of being was misguided, because he himself had shown just how far it is true that Christ is the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and end of all things. Hence there is nothing in all creation that is not oriented toward him, nothing whose “nature” is not fulfilled in “grace.” For Long as for Balthasar, the difference between Barth’s analogia fidei and this Christological version of the analogia entis is so small as to be negligible.

A major subplot of the book is theology’s conditions of possibility. Both the neo-scholastics and the radical Barthians are confident that they are serving the interests of the economy of grace, by ensuring that it is connected to “reality.” For the Thomists, reality means pure nature; for the Barthians, it means an act of election whose historical character must be brought into the very heart of the Trinity. The one school is metaphysical, the other anti-metaphysical, but both share a characteristic modern concern for rational clarity. While Long has a high respect for the work of philosophers, as a theologian he shares what George Hunsinger has called Barth’s “high tolerance for mystery,” and is therefore suspicious of attempts to reduce the complex harmonies of theology to a rationalist monotone. (In true Barthian and Balthasarian fashion, the book abounds in musical metaphors.) Christ must not be sacrificed on the altar of philosophical systems. Or for that matter, on the altar of theological politics: at several points, Long suggests that his opponents’ views are too much shaped by church-political interests. For the neo-scholastics, claims about pure nature lead directly to claims about the ordering of society: if we know with clarity what human nature is, why not enshrine it in law? (96–98). For the radical Barthians, an actualistic doctrine of election serves the interests of Reformed identity, giving a demoralized Protestantism something to be “about” (111; this is my formulation, but I think Long would agree). Of course, such criticisms can always be directed back at the one who makes them. Are evangelical Catholics like Long (and myself) so deeply committed to the cause of Christian unity—talk about demoralized!—that we have become suspiciously “soft on truth”? Perhaps. The via media is not only a difficult way, but may be the way of self-deception. Thus Barth’s ambivalent attitude toward ecumenism. He feared that a rush toward the middle might compromise the singularity of Jesus Christ, “the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death,” in the words of the Barmen Declaration.

Barth famously confessed that if he were forced to choose between the evils of Roman Catholicism and modernist Protestantism he would unhesitatingly choose the former; of course he did not believe any such choice was necessary. There is a similar revealing moment in Long’s book. In the course of discussing Kevin Hector’s Theology without Metaphysics, a “therapy” aimed at helping us overcome metaphysical nostalgia, Long admits that if “forced to choose between [the neo-Thomists’] version of Thomism and Hector’s therapy, I would tend toward Hector’s therapy” (169). Why is that? Long does not tell us in so many words. The impression he conveys, though, is that while Hector may have conceded far too much to Heidegger in his effort to speak of God, it is nevertheless God—the triune God!—he intends to speak of. Whereas in the case of the neo-Thomists, the doctrine of pure nature requires the positing of a putative realm “outside” Christ, which must then laboriously be related to him: Christ as theological afterthought. It should be noted that Long does not think the problem lies with Aquinas himself, who, as Balthasar well knew, can be read in a way such that theology clearly takes the lead over metaphysics. Among the neo-Thomists only Thomas Joseph White seems to catch a glimmer of this, and Long’s criticisms of him are accordingly far more measured.

The danger Long courts in all of this is allowing his opponents to dictate the terms of the debate. The point of overcoming the misreadings of Barth and Balthasar, after all, is not to perpetuate the contemporary metaphysics wars, but to retrieve their particular way of doing theology—talk about God. While Long can do scholastic theology with the best of them, it is in the book’s later chapters, devoted to the material loci God-ethics-ecclesiology, that he really shines. Of the making of books on Barth’s ethics there seems to be no end—rather surprising, given the severe criticisms to which it has been subject—yet Long’s retracing of this familiar ground is fresh and full of insight. A key ecumenical question emerges at this point: to what extent is the Christian ethical subject an “ecclesial subject”? Barth’s and Balthasar’s sensibilities are quite different here, with Barth subjecting the Christian directly to the command of God by virtue of his or her election, and Balthasar envisioning hierarchical vocations within the one body of Christ (laity, clergy, religious, etc.). Taking Balthasar’s side in these debates, Long raises the question whether the mature Barth’s understanding of the human subject doesn’t in the end float above history, just to the extent that it fails to make room for the church: “If the church as Christ’s body is not extended in time, creation loses its purpose. It becomes void of theological significance. For Balthasar, in opposition to Barth, creation has different gradations of proximity to the Christological center” (230).

These are very big claims—too big to address adequately in this review. I will simply press one point. First, granted that Barth was wrong about sacramental mediation—I agree with Long on this—does this mean he was also wrong to reject the notion of the church as “prolongation of the incarnation”? How does Long’s advocacy of this notion comport with his acknowledgment that “Barth’s laudable concern is to avoid identifying Jesus’ unique hypostatic union with the church and produce an ecclesial triumphalism”? (215). For that matter, I wonder how characteristic the “prolongation” idea is even of Balthasar. Long adduces a single quotation where Balthasar states: “The Church is the prolongation of Christ’s mediatorial nature and work and possesses a knowledge that comes by faith” (230). Yet if by faith, any sense of “prolongation” must be strongly qualified. To this one would have to add Balthasar’s construal of the church in terms of Mary—precisely an “other” to Christ—and his theology of the church as “chaste whore.” In general, the prolongation-idea seems a clumsy and, as Long himself notes, potentially disastrous way of affirming the totus Christus.

The chapter on ecclesiology proper, however, is my favorite (chapter 6, “The Realm of the Church: Renewal and Unity”). This is where Long takes us inside Barth’s 1941 seminar on the Council of Trent, focused on the sacraments, and at which Balthasar was present. The fact that we have detailed student protocols of this seminar makes it possible to reconstruct the give and take of theological argument. This encounter was anything but an irenic rush toward the middle. Barth and his students asked whether there is any role for faith in Catholic sacramental teaching, given the emphasis on sacraments as “causes” of grace—ex opere operato—while for his part Balthasar asked why secondary causes should be seen as detracting from God’s glory: “Is it irksome for Rembrandt to use a brush?” (256). Balthasar’s strong affirmation of the personal, appropriative force of the sacraments, as well as their sign-character, certainly gave the Protestants a great deal to think about. The participants in the seminar did not claim to have resolved all the confessional differences. What is striking, however, is the extent to which popular perceptions of Catholic and Protestant sacramental teaching, and even some scholarly accounts, still have not risen to the level of understanding Barth and Balthasar achieved in 1941. Clearly there is a great deal of ecumenical work still to be done.

This is a necessary book for our theological moment. Although I have dwelt on its polemical features—and the polemics are indeed integral to the argument—it would be unfortunate if the book were seen mainly as being “against” certain positions. As in the work of both his authors, the Nein stands in service of the Ja—God’s great “Yes” to humanity in Jesus Christ. But to live from Christ means participating in the passion to which he, the Son of God, freely subjected himself on our behalf. Early in the book, Long comments that from his theological beginnings “Barth chose, in his words, to ‘suffer’ Catholicism. It was a worthy adversary. But if Barth suffered Catholicism, Balthasar returned the favor” (14). As Long well documents, Balthasar literally suffered a certain alienation from his own communion because of his odd preoccupation with the Reformed theologian from Basel. Without valorizing or sentimentalizing these thinkers, who were certainly not without their faults, we may perhaps see them as figures for our divided churches. Both tried to live and think from the center—not a cheap middle way, but Christ the Center. Both lived from the incarnation and cross to such an extent that they could confront each other non-defensively and even joyfully. Not accidentally, their theological encounter took the form of friendship, which means spending time with the other, literally “suffering” his or her presence for Christ’s sake. It would be a fine thing if Saving Karl Barth became an occasion for more such friendships.

Response

On Being Modern, a Methodist, and the Analogy of Being

It seems strange to call a former mentor and current friend “Long,” so at the costs of seeming insubordinate I’ll refer to the author of Saving Karl Barth as “Steve.” As a longer review of Steve’s remarkable book will be forthcoming elsewhere,1 the following will consist mainly of observations followed by questions and will be informal in tone. I realize that this interrogative format puts additional burdens of time and energy upon Steve, but it’s too difficult to avoid the temptation of indulging my curiosity and yet again “raising my hand” to ask a past and present teacher some questions. I would, then, be happy with simply vague or general impressions.

On Being Modern

“Being modern” is said in many ways. The list of scholars who read Karl Barth as modern is long and varied and for each scholar handles Barth’s “being modern” in different ways. Ingrid Spieckermann and Bruce McCormack have focused on modern epistemological inheritances, Trutz Rendtorff and Gerald McKenny on modern ethical commitments (particularly that of autonomy), while others have seen Barth’s “being modern” in the context of his theological decisions within his doctrine of Scripture; his revisions of the doctrines of election and divine simplicity and impassibility; his stress that God’s being is always a free and loving being-in-act; his distinction between Historie and Geschichte and his use of Saga; his deeply respectful yet judicious listening to traditional Protestant creeds and confessions; his wariness to natural theology in both theological and political forms, and the list could go on. While these modern commitments irreducibly shape and inform Barth’s theology, they do not exhaust it. Equally, some of these commitments figure more prominently in Barth’s theology while others play a fairly minor role. It is also clear that Barth can often ignore, excoriate, or run roughshod over the concerns of modern theology, and thankfully so.

Given that Steve is attempting to pushback against a line of Barth interpretation that he sees rendering Barth a modern, postmetaphysical, and ecumenically limited theology, it makes sense that Barth’s modern inheritances are not addressed at length and that Barth is often seen as overcoming the problems of modernity. For instance, in a passage dealing with readings of Barth’s doctrine of God, Steve can write, “By providing an alternative to the deus absconditus, Barth poses a challenge to a core thesis of modern theology. Barth is not a modern theologian, but one who provides a doctrine of God to heal a modern theology that too often confused the Christian God with Isis” (154). I would, however, see no contradiction in stating that Barth is an irreducibly yet not slavish modern theologian who could overcome one problem within modern theology (or better put, a problem within some doctrines of God since the Late Medieval Period) while nevertheless remaining modern in many other ways.

My question to Steve, then, is what he would make of Barth’s modern inheritances and whether he thinks it helpful or distracting to focus on or develop them. If this question is too broad or unclear, then perhaps a more focused question could be addressed: what is Steve’s understanding of the role of Kantian or critical philosophy, either in its practical or theoretical forms, in Barth’s work. While it is a tiresome question, it is still commonly misunderstood by being either overestimated or underappreciated.

On Being Methodist

While Steve is an ordained Methodist elder, his instincts and views on various issues can run the theological gambit: from approaching the Roman Catholic to nearing the Anabaptist. Nevertheless, as so richly portrayed in a recent article for The Christian Century,2 the Methodists are those folk who have guided him and given to him, and they are the same folk who in turn keep asking him to do things. Throughout the book Steve can both appreciate and blast the “postmetaphysical Barthians” and the “Ressourcement Thomists,” even admitting at one point that he would choose the former if forced to decide. Yet in the second, more doctrinal half of the book, one gains the impression that Steve feels more at home in von Balthasar’s roomy, Christocentric Catholicism than in Barth’s equally roomy (though it may not appear so at times), Christocentric Protestantism. Perhaps this impression is merely a misimpression, but my question to Steve would be whether his time with the Methodists has tilted his hand towards von Balthasar. One could imagine Wesleyan intuitions on sanctification and holiness, prevenience grace, communal discipleship, constant communion, catholicity, the intimate relationship between doctrine and life, etc., as providing just such an impetus for generally leaning towards von Balthasar. If being Methodist is in fact not such an impetus, I would be grateful to hear a bit more about this apparent leaning more towards von Balthasar than to Barth.

On the Analogy of Being

In the course of posing some questions to the Ressourcement Thomists regarding metaphysics and the intelligibility of the incarnation, Steve offers the following:

“If this conditioning of revelation is correct, then to put it whimsically, we will need to correct Scripture. Jesus would have to counter Thomas’s confession in John 20:28, ‘My Lord and my God,’ without something like, ‘Well I know you think you know what this means, but you cannot make this confession properly until you become aware it is conditioned by the analogia entis found in Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics taken up by the Thomist manual tradition after the thirteen century’”3 (169).

The above passage comes from a section entitled “What is at stake in the analogia entis?” While Steve levels criticisms at any account of the analogy of being which views it as a metaphysical framework which conditions revelation, as well as criticisms at those who attempt to circumvent metaphysics pragmatically, the reader is still left with what Steve himself thinks is at stake. Generally speaking, Steve seems well-disposed towards the analogy of being as promoted by von Balthasar (and perhaps by Przywara), and yet it would be good to hear more of what Steve thinks about the use of the analogy of being within theology, particularly within the context of Christology as raised in the passage above. I realize that entire monographs have been dedicated to these issues, but I would be grateful to hear Steve think out loud.

12.14.14 | George Hunsinger

Response

A Yawning Chasm Not Easily Closed

I think this is really an exciting piece of work. Being very well-researched and groundbreaking in its use of materials from the von Balthasar archive, it brings a fresh perspective to our understanding of Karl Barth and of his relationship with his close Catholic friend. I learned a lot I didn’t know from reading it. I am happy to recommend this book highly, though I have reservations about a few of its lesser arguments.

First, a small but not unimportant point about how to translate a particular phrase. Long regularly comes back to a remark made by Barth in the first volume of his Church Dogmatics. Barth is trying to get a handle on what it is that finally separates the Roman Catholic church from the churches of the Reformation. When God’s Word is proclaimed, he asks, is Christ’s action tied to the ecclesiastical office of the minister, or is it actually the other way around, namely, that the office is tied to Christ’s action whenever the Word is “actualized,” or “made effectual,” through preaching? The first would be the Catholic view, while the second would be the Reformation’s.

Barth wants to insist with the Reformation that the saving efficacy of the church’s ministry resides in Christ alone, who bears witness to himself through the preaching of the church. The saving efficacy of preaching is not divided between Christ and the minister, along the lines, say, of primary and secondary causality. Causality thinking, Barth contends, is out of place when it comes to understanding the mystery of divine and human action. For Barth, there is only one Saving Agent, and his name is Jesus Christ. When others act in and through Christ as his instruments and witnesses, they acquire no secondary saving agency of their own. No matter if there is more than one acting subject, there is always only one Saving Agent. The issue can then be rephrased: Is there only one Saving Agent at work in the ministry of the church, or are there many lesser ones alongside the One who is supreme? Barth observes: “From the standpoint of our theses this question is the puzzling cleft which has cut right across the church during the last 400 years” (I/1, 99).

Long regularly re-translates the German in Barth’s observation—der rätselhafte Riß—as “the enigmatic cleft.” The author resorts to other variants as well, but this is the one he prefers. However, the phrase might better be rendered as “the perplexing rift” or “the vexing split.” The noun der Riß has connotations of “rupture” more nearly than of “cleft.” Barth is pointing to a conception of human action in relation to God’s grace that has torn the fabric of the church for more than 400 years. While the translation problem is minor, the issue to which it points is not. I will return to it in due course.

At the heart of Long’s book is a contrast between a form of “neoscholastic retrenchment” in Roman Catholic theology as over against a “modernizing” or “post-metaphysical” movement in Protestant circles that would claim Barth as their supposed forebear. The neoscholastics are critical of Balthasar for being too influenced by Barth while the post-metaphysical claimants seem to confirm their deepest fears about where Barth goes wrong. Although Long overstates the influence of these two groupings—I don’t think their combined forces have led to the “collapse” of Balthasar’s interpretation of Barth—they have at least put a dent in it. Long is right to worry that they are having a baleful influence on a younger generation of scholars, and more importantly that they create unfortunate and finally specious obstacles to the future of ecumenical rapprochement.

I want to concentrate on Long’s critique of those Protestants who would argue that Barth is a “post-metaphysical” theologian, at least by implication, because he is alleged to be “thoroughly modern.” I agree with Long that, among other things, this line of interpretation overstates the degree to which Barth was influenced by Kant. Barth’s theology arguably includes “modern,” “post-modern,” and even “pre-modern” elements all at once. It would be better to characterize his theology as “thoroughly eclectic.” Only by being happily eclectic could Barth proceed with his project of trying to take every thought captive in obedience to Christ without becoming a captive to modernity himself.

Long singles out six features in the new “post-metaphysical” Barth interpretation, which if adopted would “radically revise the Christian doctrine of God” (148).

In short, “if the processions and missions must be held together as an eternal act, then not only the Son’s humanity but all of creation would need to be eternal” (149). As Long rightly observes, the later Barth repeatedly blocks such moves as we find in this line of Barth interpretation. Long rightly quotes Barth: “In the inner life of God, as the eternal essence of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, the divine essence does not of course, need any actualization” (IV/2, 113). This is far from an isolated remark. For the Barth of Church Dogmatics, from beginning to end, God does not need the world in order to be God, nor is there any element of contingency in God’s being.

Long is also correct when he appeals to Aquinas for whom the “missions” are not eternal, because Aquinas posited that it was possible for God to do something temporally that did not require God to actualize a potential. This is Barth’s view as well. For Barth as for Aquinas, “creation does not add something to, or take away from, God” (149), i.e., to God’s eternal essence.

Like Aquinas, Barth always affirmed that God’s triune being was pure act, that it was perfect and sufficient in itself, and that it did not exclude a distinction between God’s “absolute being” and his “contingent will” (III/1, 15). Barth openly aligned himself with the medieval Dominican in this regard. He noted that Aquinas upheld “the most important statement in the doctrine of creation—namely, that of the novitas mundi [contingency of the world]” (III/1, 4 rev.). Barth also endorsed Aquinas’s teaching “that the world is not eternal but has a beginning.” He agreed with him that the idea of creation’s contingency “is only credibile, non autem scibile et demonstrabile [a matter of belief, not of immediate knowledge or rational demonstration] (S. theol., I, qu. 46, art. 2c)” (III/1, 4). On all such matters the actually existing textual Barth is far closer to Aquinas than to Hegel and the Barth revisionists.

The revisionist line of Barth interpretation that Long challenges can only maintain itself by ignoring a great deal of contrary textual evidence. It attempts to do so mainly by claiming that the later Barth is “inconsistent.” On those grounds, it proceeds as if all contrary textual evidence in the Church Dogmatics can simply be brushed aside. These are complicated questions that cannot be pursued here. I deal with them extensively, however, in my forthcoming book Reading Barth with Charity: A Hermeneutical Proposal (Baker Academic, 2015). For the time being I would simply like to align myself with the line of questioning that Stephen Long so trenchantly sets forth.

In conclusion, I want to turn to a matter touched on at the outset. Professor Long admirably wants to look for ways in which the historic divisions between Roman Catholic theology and Protestant theology can be overcome. One of the neuralgic points to which he returns throughout his book is the question of whether the church can properly be described as a “prolongation of the incarnation.” This is one of the deepest differences that Long identifies as separating Balthasar and Barth (285–86). For Balthasar if the church is not the prolongation of the incarnation, there is no historical drama of God’s actions through the church (no “theodrama”) (230). For Barth, who rejected this idea as “blasphemy” (IV/3, 729), it illicitly elevates the church to the point where it not only acts alongside Christ, but in practice even above him “as his vicar in earthly history” (IV/3, 36). The only proper view for Barth was one where the church was always completely subordinate to Christ, never alongside or above him. The church was always in the position of an absolute dependence on grace, which for Barth meant the position of prayer.

The intractability of this issue is only intensified when it is recognized, as Long notes, that in Lumen Gentium the church is still referred to as the extension of the incarnation (216 n.123). Long can’t understand why Barth refuses to follow Balthasar on this question. He implies that he himself agrees with Balthasar in holding that Barth fails to have “an adequate account of human agency” (230).

It is, however, tendentious to accuse Barth’s view of being “inadequate” without probing into the deeper issues. What counts as “adequate” is precisely what is contested between Catholicism and the Reformation. Balthasar strives heroically to construct a view of the incarnatus prolongatus that would escape from many of the Reformation’s objections. (219). He cannot escape, however, from upholding the idea that human actors can play some auxiliary causal or contributory role, apart from and alongside Christ, in carrying out the work of salvation. This observation pertains especially to Balthasar’s view of Mary and the ordained ministry of the church (presbyters, bishops, and the pope).

Balthasar cannot strictly uphold the Reformation’s fundamental conviction that human salvation occurs sola fide, sola gratia, and solus Christus. There is a yawning chasm between the idea of “Christ alone” and that of “Christ primarily.” For Barth and the Reformation, the faithful actions of human beings give them the status of being “witnesses,” and even “mediators,” but without ever making them into secondary “Saving Agents,” which could only mean their usurping of the incommunicable office and inviolable dignity of the Lord Jesus Christ. For Barth and the Reformation, everything believers may do is at its best an act of gratitude, never one with any claim to “merit” before God. Barth’s view might not convince Balthasar and his contemporary adherents, but it should not be perplexing as to why he holds it. For him, the church is always a witness to the incarnation, never in any sense an extension of it.

Divine and human action are, as I argue in How to Read Karl Barth (Oxford, 1991), always related for Barth by means of the Chalcedonian Pattern. They are related “without separation or division” (inseparable unity), “without confusion or change” (abiding distinction), and with an “asymmetrical ordering principle” (the absolute primacy and precedence belong always to God). Within this fundamental structure divine and human agency are non-competitive. For Barth in line with the Reformation, Catholic views of divine and human agency regularly violate the stricture against confusion or change, and especially against compromising the principle of asymmetry.

12.24.14 | D. Stephen Long

Reply

Response to George Hunsinger

I am deeply grateful to George Hunsinger for his review of my book, and for the many contributions he made to it through his own work. It will come as no surprise to our readers that he agrees with my critique of the postmetaphysical Barthians. Much of my critique echoes his. On the whole he and I do not disagree on any substantial descriptive or interpretive matters. I am pleased he thinks I am correct that the postmetaphysical Barthians overstate the influence of Kant on Barth. He likewise recognizes how that overstatement plays into the hands of some Roman Catholic theologians who claim Roman Catholicism alone protects reason from the historicizing fideism of modernity and Protestantism (See Matthew Rose’s “Karl Barth’s Failures” in First Things for another familiar version of this narrative. One goal I had in this book is to at least problematize that familiar narrative). If Barth is the modern Kantian some assume he is, that version of Catholic theology has warrant for its judgment that Barth failed to deliver theology from modernity (wrongly assuming, of course, that modern historicism and Medieval metaphysics must be set in opposition as the Thomists of the strict observance do in a very modern gesture.) I am also pleased that Dr. Hunsinger finds the convenientia between Aquinas and Barth that I find convincing. Perhaps Dr. McCormack is moving in that direction as well, given his essay in Thomas Aquinas and Karl Barth: An Unofficial Catholic-Protestant Dialogue. That important book was not available to me when I was working on Saving Karl Barth. If I have interpreted Dr. McCormack correctly, it would require me to nuance some of my criticisms. One criticism Dr. Hunsinger makes of my interpretive work is that I overstated the collapse of Balthasar’s interpretation among Barthian theologians. He suggests it still has significant traction. The positive assessment my defense of Balthasar’s reading has garnered among some of them suggests he is right.

The significant issue between us is not primarily interpretive but evaluative, although the two cannot be decisively separated. Dr. Hunsinger points to the phrase der rätselhafte Riß and its interpretation as key. The statement appears in Church Dogmatics I.1 and forms the basis for Balthasar’s engagement with Barth’s theology. The “puzzling rupture” between Catholics and Protestants, Barth and Hunsinger suggest, is a question of the relation between divine and human agency. Here is how Barth puts it, “Is Christ’s action, real proclamation, the Word of God preached, tied to the ecclesiastical office and consequently to a human act, or conversely, as one might conclude from this oret are the office and act tied to the action of Christ, to the actualizing of proclamation by God, to the Word of God preached? From the standpoint of our theses this question is the puzzling cleft which has cut right across the church during the last 400 years.” I cite the passage on page 242, and suggest that it does not fit well Barth’s affirmation of Reformed preaching if Barth distinguishes the Divine act from the human act. I stated, “Barth sets Jesus’ role over and against the church, rather than within it, which does not fit seamlessly with his previous argument that the Word and proclaimer are one, not two.” Here we may have a disagreement in our interpretation of Barth.

Before Barth uses the term “der rätselhafte Riß,” he makes a surprising turn. He admonishes his reader not to side with Harnack and take offense at the Catholic teaching that the bishop can be vicarius Chrisi. Barth writes, “One can neither estimate the Roman Catholic position correctly nor take up the correct Evangelical position if (with Harnack, op. cit., 446) one takes offence already at the idea of vicariate or succession. One would have to deny Christus praesens to deny in principle the vicarius Christi. The difference between Roman Catholic dogmatics and ourselves, which, of course, we must always keep in view, cannot refer to the fact of this vicariate or succession, but only to its manner” (CD I.1, 97). I find it fascinating that Barth affirms the possibility that because of Christ’s presence to his church, the vicarius Christi should not a priori be denied. What he then rejects about Roman Catholicism is that it “dehumanizes” the bishop in order to affirm the vicarius Christi. Does that not suggest the possibility that Christ’s presence makes possible the bishop as the vicar of Christ in his humanity? I interpret Barth as suggesting this possibility. Notice that in the quotation Hunsinger points to, Barth does not explicitly reject the “human act.” He asks if “institution and act” are tied to Christ’s act. He has a role for the human act, but not if it is the condition for the Divine act. If that interpretation is correct, then Balthasar would be incorrect when he faults Barth for failing to have an adequate account of human agency. Dr. Hunsinger thinks I have sided with Balthasar in attributing such a failure to Barth. His interpretation is understandable but not quite right. I think Barth demonstrated he had a more robust account of human agency in the realm of grace than Balthasar and perhaps Hunsinger suggest. It will come to flourish in Barth’s remarkable question in his Doctrine of Reconciliation, “Is it really the case that He has caused His Word to become flesh not merely in order that He may be an act for us in His own person, but in order that we may also be an act for Him?” (CD 4.2 791). Barth assumes the answer is yes. The only way to make sense of such a claim without falling into the silliness of a process metaphysics or some of the revisionary metaphysics Barthians are setting forth today would be to affirm secondary causality in which we acknowledge God’s “primary causality” is never in competition with it. So my argument is that Barth did have a strong account of human agency even in the mediation of grace and this is found in the unity of Divine Word and the preacher in proclamation, a unity that does not reject the humanity of the preacher. It is a unity because these two forms of causality are never in competition. My critique of Barth then was this: “He [Barth] denies to the Catholic Eucharist what he affirms for Reformed preaching” (242).

I do not think what I just stated disagrees with Dr. Hunsinger’s statement:

“The only proper view for Barth was one where the church was always completely subordinate to Christ, never alongside or above him. The church was always in the position of an absolute dependence on grace, which for Barth meant the position of prayer.”

All theologians should affirm this. Do Catholics deny it? Yves Congar makes a great deal of the importance of the prayer that begins the Mass: “the Lord be with you—and with your spirit.” It suggests that even though all is in good order with the office and institution, unless there is a prayer for the Spirit, “the Lord,” everything remains ineffectual. The Mass is not a technology that dispenses grace; it is a prayer. If this is the case, then the “rupture” is all the more puzzling. We remain unsure what divides us. Barth’s criticism of Catholicism could be construed as a charge that it is a kind of gnosticizing where the human materiality of the priest, like the materiality of the bread and wine, have to be evacuated for Divine agency to work. If so, then it would be Barth who affirmed a more Medieval and patristic outlook in which Divine and human agency become one without divinity ceasing to be divinity or humanity humanity.

Balthasar picks up on Barth’s expression “der rätselhafte Riß” because he sees in it a “crack,” or opening, for a Catholic-Protestant conversation. It is the reason he titles the first chapter of his Barth book, “Zerrissene Kirche.” If the rupture is fully intelligible on either side, then there is no need for a conversation. Conversion of one side to the other is the only way forward; all other approaches are closed. If the rupture is “puzzling,” then an opening exists. We do not yet know if the rupture is irremediable because we remain uncertain as to what and why it is. Hunsinger is also correct that the disagreement between us is related to the question whether the church should be spoken of as the extension of the Incarnation. Because Joseph Mangina will raise a similar concern in his review, I will address that important question at that point.